Guru Angad

Guru Angad ([gʊɾuː əŋgəd̯ᵊ]) was an Indian religious leader and the second of the ten Sikh gurus. He was born in a Hindu family, with the birth name as Lehna, in the village of Harike (now Sarae Naga, near Muktsar) in northwest Indian subcontinent.[2][3] Bhai Lehna grew up in a Khatri family (Kshatriya, traditionally warriors), his father was a small scale trader, he himself worked as a pujari (priest) and religious teacher centered around goddess Durga.[3][4] He met Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, and became a Sikh. He served and worked with Guru Nanak for many years. Guru Nanak gave Lehna the name Angad ("my own limb"),[5] and chose Angad as the second Sikh Guru.[3][4][6]

Guru Angad Dev Ji | |

|---|---|

Fresco of the second Sikh Guru at Goindval | |

| Personal | |

| Born | Bhai Lehna April 10, 1504 Matte Di Sarai, Muktsar, Panjab |

| Died | April 8, 1552 (aged 48) |

| Religion | Sikhism |

| Spouse | Mata Khivi |

| Children | Baba Dasu, Baba Dattu, Bibi Amro, and Bibi Anokhi |

| Parents | Mata Ramo and Baba Pheru Mal |

| Known for | Standardising the Gurmukhi Script |

| Religious career | |

| Predecessor | Guru Nanak |

| Successor | Guru Amar Das Ji |

| Part of a series on |

| Sikhism |

|---|

|

|

|

Practices

|

|

|

General topics

|

After the death of Guru Nanak in 1539, Guru Angad led the Sikh tradition.[7][8] He is remembered in Sikhism for adopting and formalizing the Gurmukhi alphabet based on the then prevalent local Devanagari script.[2][4] He began the process of collecting the hymns of Guru Nanak, contributed 62 or 63 hymns of his own.[4] Instead of his own son, he chose a Vaishnava Hindu Amar Das as his successor and the third Guru of Sikhism.[7][8]

Biography

Guru Angad was born in a village, with birth name of Lehna, to Hindu parents living in northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent called the Punjab region. He was the son of a small but successful trader named Pheru Mal. His mother's name was Mata Ramo (also known as Mata Sabhirai, Mansa Devi and Daya Kaur).[9] Like all the Sikh Gurus, Lehna came from Khatri caste.[10]

At age 16, Angad married a Khatri girl named Mata Khivi in January 1520. They had two sons (Dasu and Datu) and one or two daughters (Amro and Anokhi), depending on the primary sources.[9] The entire family of his father had left their ancestral village in fear of the invasion of Babar's armies. After this the family settled at Khadur Sahib, a village by the River Beas near what is now Tarn Taran.

Before becoming a Sikh and his renaming as Angad, Lehna was a religious teacher and priest who performed services focussed on Durga (Devi Shaktism, the goddess tradition of Hinduism).[3][4][9] Bhai Lehna in his late 20s sought out Guru Nanak, became his disciple, and displayed deep and loyal service to his Guru for about six to seven years in Kartarpur.[9][11]

Selection as successor

Several stories in the Sikh tradition describe reasons why Bhai Lehna was chosen by Guru Nanak over his own sons as his choice of successor . One of these stories is about a jug which fell into mud, and Guru Nanak asked his sons to pick it up. Guru Nanak's sons would not pick it up because it was dirty or menial a task. Then he asked Bhai Lehna, who however picked it out of the mud, washed it clean, and presented it to Guru Nanak full of water.[12] Guru Nanak touched him and renamed him Angad (from Ang, or part of the body) and named him as his successor and the second Nanak on 23 June 1539.[9][13]

After the death of Guru Nanak on 2 October 1539, Guru Angad left Kartarpur for the village of Khadur Sahib (near Goindwal Sahib). This move may have been suggested by Guru Nanak, as the succession to gurgaddi (seat of Guru) by Guru Angad was disputed and claimed by the two sons of Guru Nanak: Sri Chand and Lakhmi Das.[2] Post succession, at one point, very few Sikhs accepted Guru Angad as their leader and while the sons of Guru Nanak claimed to be the successors. Guru Angad focussed on the teachings of Nanak, and building the community through charitable works such as langar.[14]

Relationship with the Mughal Empire

The second Mughal Emperor of India Humayun visited Guru Angad at around 1540 after Humayun lost the Battle of Kannauj, and thereby the Mughal throne to Sher Shah Suri.[15] According to Sikh hagiographies, when Humayun arrived in Gurdwara Mal Akhara Sahib at Khadur Sahib Guru Angad was sitting and teaching children.[16] The failure to greet the Emperor immediately angered Humayun. Humayun lashed out but the Guru reminded him that the time when you needed to fight when you lost your throne you ran away and did not fight and now you want to attack a person engaged in prayer.[17] In the Sikh texts written more than a century after the event, Guru Angad is said to have blessed the emperor, and reassured him that someday he will regain the throne.[14]

Death and successor

Before his death, Guru Angad, following the example set by Guru Nanak, nominated Guru Amar Das as his successor (The Third Nanak). Before he converted to Sikhism, Amar Das had been a religious Hindu (Vaishnava, Vishnu focussed), reputed to have gone on some twenty pilgrimages into the Himalayas, to Haridwar on river Ganges. About 1539, on one such Hindu pilgrimage, he met a Hindu monk (sadhu) who asked him why he did not have a guru (teacher, spiritual counsellor) and Amar Das decided to get one.[7] On his return, he heard Bibi Amro, the daughter of the Guru Angad who had married into a Hindu family, singing a hymn by Guru Nanak.[18] Amar Das learnt from her about Guru Angad, and with her help met the second Guru of Sikhism in 1539, and adopted Guru Angad as his spiritual Guru who was much younger than his own age.[7]

Amar Das displayed relentless devotion and service to Guru Angad. Sikh tradition states that he woke up in the early hours to fetch water for Guru Angad's bath, cleaned and cooked for the volunteers with the Guru, as well devoted much time to meditation and prayers in the morning and evening.[7] Guru Angad named Amar Das as his successor in 1552.[8][18][19] Guru Angad died on 8 April 1552.[9]

Influence

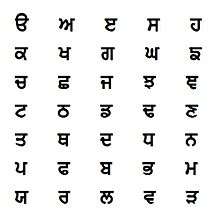

Gurmukhi script

Guru Angad is credited in the Sikh tradition with the Gurmukhi script, which is now the standard writing script for Punjabi language in India,[20] in contrast to Punjabi language in Pakistan where now an Arabic script called Nastaliq is the standard.[21] The original Sikh scriptures and most of the historic Sikh literature have been written in the Gurmukhi script.[20]

Guru Angad's script modified the pre-existing Indo-European scripts in northern parts of the Indian subcontinent.[22] The script may have already been developing before the time of Guru Angad, because there is evidence that at least one hymn was written in acrostic form by Guru Nanak, which state Cole and Sambhi gives proof that the alphabet already existed.[23] A part of the popular Sikh belief is that Guru Angad invented the script, but this belief lacks evidence and is suspect.[24]

Guru Angad started the tradition of Mall Akhara (wrestling), where physical as well as spiritual exercises were held. He also wrote 62 or 63 Saloks (compositions), which together constitute about one percent of the Guru Granth Sahib, the primary scripture of Sikhism.[25]

Langar and community work

Guru Angad is notable for systematizing the institution of langar in all Sikh temple premises, where visitors from near and far could get a free simple meal in a communal seating.[2][26] He also set the rules and training method for volunteers (sevadars) who operated the kitchen, placing emphasis on treating it as a place of rest and refuge, being always polite and hospitable to all visitors.[2]

Guru Angad visited other places and centres established by Guru Nanak for the preaching of Sikhism. He established new centres and thus strengthened its base.[2]

Mall Akahara

The Guru, being a great patron of wrestling,[27] started a Mall Akhara (wrestling arena) system where physical exercises, martial arts, and wrestling was taught as well as health topics such as staying away from tobacco and other toxic substances.[28][29] He placed emphasis on keeping the body healthy and excersising daily.[30] He founded many such Mall Akharas in many villages including a few in Khandur.[31] Typically the wrestling was done after daily prayers and also included games and light wrestling.[32]

References

- H. S. Singha (2000). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (over 1000 Entries). Hemkunt Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-81-7010-301-1.

- Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 35–37. ISBN 978-1-4411-0231-7.

- Louis E. Fenech; W. H. McLeod (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1.

- William Owen Cole; Piara Singh Sambhi (1995). The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 18–20. ISBN 978-1-898723-13-4.

- Clarke, Peter B.; Beyer, Peter (2009). The World's Religions: Continuities and Transformations. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 565. ISBN 9781135210991.

- Shackle, Christopher; Mandair, Arvind-Pal Singh (2005). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. United Kingdom: Routledge. xiii–xiv. ISBN 0-415-26604-1.

- Kushwant Singh. "Amar Das, Guru (1479–1574)". Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Punjab University Patiala. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- William Owen Cole; Piara Singh Sambhi (1995). The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-1-898723-13-4.

- McLeod, W.H. "Guru Angad". Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Punjabi University Punjabi. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- Shackle, Christopher; Mandair, Arvind-Pal Singh (2005). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. United Kingdom: Routledge. p. xv. ISBN 0-415-26604-1.

- Sikka, A.S. (2003). Complete Poetical Works Of Ajit Singh Sikka. Atlantic Publishers and Distribution. p. 951.

- Cole, W. Owen; Sambhi, Piara Singh (1978). The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. 18. ISBN 0-7100-8842-6.

- Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 41–44. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Singh, Pashaura; Fenech, Louis (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies (First ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 41. ISBN 9780191004124.

- Singh, Ajit (2005). Suraj Prakash Granth part 5 ras 4. p. 177. ISBN 81-7601-685-3.

- Singh, Gurpreet (2001). Ten Masters. New Delhi: Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. p. 53. ISBN 9788171829460.

- Louis E. Fenech; W. H. McLeod (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1.

- H. S. Singha (2000). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (over 1000 Entries). Hemkunt Press. pp. 14–17, 52–56. ISBN 978-81-7010-301-1.

- Shackle, Christopher; Mandair, Arvind-Pal Singh (2005). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. United Kingdom: Routledge. pp. xvii–xviii. ISBN 0-415-26604-1.

- Peter T. Daniels; William Bright (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. p. 395. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4411-0231-7.

- Cole, W. Owen; Sambhi, Piara Singh (1978). The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. 19. ISBN 0-7100-8842-6.

- Danesh Jain; George Cardona (26 July 2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 594–596. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- Shackle, Christopher; Mandair, Arvind-Pal Singh (2005). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. United Kingdom: Routledge. p. xviii. ISBN 0-415-26604-1.

- Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Green, Thomas (2010). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation, Volume 2. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 286. ISBN 9781598842432.

- Sharma, Rajkumar (2014). Second Sikh Guru: Shri Guru Angad Sahib Ji. Lulu Press. ISBN 9781312189553.

- Chowdhry, Mohindra (2018). Defence of Europe by Sikh Soldiers in the World Wars. Leicestershire: Troubador Publishing Ltd. p. 48. ISBN 9781789010985.

- Chowdhry, Mohindra (2018). Defence of Europe by Sikh Soldiers in the World Wars. Leicestershire: Troubador Publishing Ltd. p. 48. ISBN 9781789010985.

- Dogra, R. C.; Mansukhani, Gobind (1995). Encyclopaedia of Sikh Religion and Culture. Vikas Publishing House. p. 18. ISBN 9780706983685.

- Sikh Cultural Centre (2004). "Physical Fitness: Sangati Mal Akhara". The Sikh Review. 52 (1–6, Issues 601-606): 94.

Bibliography

- Harjinder Singh Dilgeer, SIKH HISTORY (in English) in 10 volumes, especially volume 1 (published by Singh Brothers Amritsar, 2009–2011).

- Sikh Gurus, Their Lives and Teachings, K.S. Duggal

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Guru Angad. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Guru Angad |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Preceded by Guru Nanak |

Sikh Guru 7 September 1539 – 26 March 1552 |

Succeeded by Guru Amar Das |