Religious text

Religious texts are texts related to a religious tradition. They differ from literary texts by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual practices, commandments or laws, ethical conduct, spiritual aspirations, and for creating or fostering a religious community.[1][2][3] The relative authority of religious texts develops over time and is derived from the ratification, enforcement, and its use across generations. Some religious texts are accepted or categorized as canonical, some non-canonical, and others extracanonical, semi-canonical, deutero-canonical, pre-canonical or post-canonical.[4]

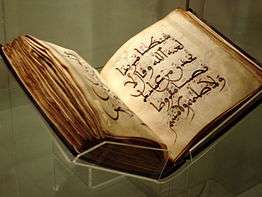

A scripture is a subset of religious texts considered to be "especially authoritative",[5][6] revered and "holy writ",[7] "sacred, canonical", or of "supreme authority, special status" to a religious community.[8][9] The terms sacred text and religious text are not necessarily interchangeable in that some religious texts are believed to be sacred because of the belief in some theistic religions such as the Abrahamic religions that the text is divinely or supernaturally revealed or divinely inspired, or in non-theistic religions such as some Indian religions they are considered to be the central tenets of their eternal Dharma. Many religious texts, in contrast, are simply narratives or discussions pertaining to the general themes, interpretations, practices, or important figures of the specific religion. In some religions (Islam), the scripture of supreme authority is well established (Quran). In others (Christianity), the canonical texts include a particular text (Bible) but is "an unsettled question", according to Eugene Nida. In yet others (Hinduism, Buddhism), there "has never been a definitive canon".[10][11] While the term scripture is derived from the Latin scriptura, meaning "writing", most sacred scriptures of the world's major religions were originally a part of their oral tradition, and were "passed down through memorization from generation to generation until they were finally committed to writing", according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica.[7][12][13]

Religious texts also serve a ceremonial and liturgical role, particularly in relation to sacred time, the liturgical year, the divine efficacy and subsequent holy service; in a more general sense, its performance.

Etymology and nomenclature

According to Peter Beal, the term scripture – derived from "scriptura" (Latin) – meant "writings [manuscripts] in general" prior to the medieval era, then became "reserved to denote the texts of the Old and New Testaments of the Bible".[14] Beyond Christianity, according to the Oxford World Encyclopedia, the term "scripture" has referred to a text accepted to contain the "sacred writings of a religion",[15] while The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions states it refers to a text "having [religious] authority and often collected into an accepted canon".[16] In modern times, this equation of the written word with religious texts is particular to the English language, and is not retained in most other languages, which usually add an adjective like "sacred" to denote religious texts.

Some religious texts are categorized as canonical, some non-canonical, and others extracanonical, semi-canonical, deutero-canonical, pre-canonical or post-canonical.[4] The term "canon" is derived from the Greek word "kανών", "a cane used as a measuring instrument". It connotes the sense of "measure, standard, norm, rule". In the modern usage, a religious canon refers to a "catalogue of sacred scriptures" that is broadly accepted to "contain and agree with the rule or canon of a particular faith", states Juan Widow.[17] The related terms such as "non-canonical", "extracanonical", "deuterocanonical" and others presume and are derived from "canon". These derived terms differentiate a corpus of religious texts from the "canonical" literature. At its root, this differentiation reflects the sects and conflicts that developed and branched off over time, the competitive "acceptance" of a common minimum over time and the "rejection" of interpretations, beliefs, rules or practices by one group of another related socio-religious group.[18] The earliest reference to the term "canon" in the context of "a collection of sacred Scripture" is traceable to the 4th-century CE. The early references, such as the Synod of Laodicea, mention both the terms "canonical" and "non-canonical" in the context of religious texts.[19]

History of religious texts

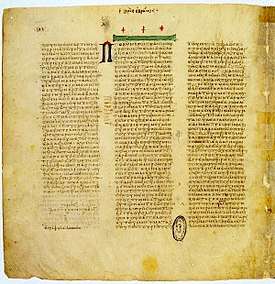

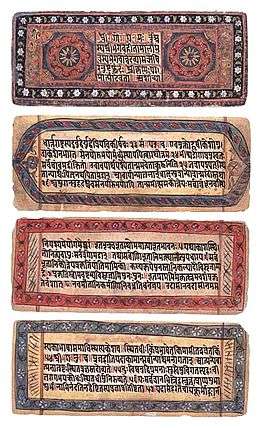

One of the oldest known religious texts is the Kesh Temple Hymn of ancient Sumer,[20][21] a set of inscribed clay tablets which scholars typically date around 2600 BCE.[22] The Epic of Gilgamesh from Sumer, although only considered by some scholars as a religious text, has origins as early as 2150 BCE,[23] and stands as one of the earliest literary works that includes various mythological figures and themes of interaction with the divine.[24] The ‘’Rig Veda’’ – a scripture of Hinduism – is dated to between 1500–1200 BCE. It is one of the oldest known complete religious texts that has survived into the modern age.[25]

There are many possible dates given to the first writings which can be connected to Talmudic and Biblical traditions, the earliest of which is found in scribal documentation of the 8th century BCE,[26] followed by administrative documentation from temples of the 5th and 6th centuries BCE,[27] with another common date being the 2nd century BCE.[27] Although a significant text in the history of religious text because of its widespread use among religious denominations and its continued use throughout history, the texts of the Abrahamic traditions are a good example of the lack of certainty surrounding dates and definitions of religious texts.

High rates of mass production and distribution of religious texts did not begin until the invention of the printing press in 1440,[28] before which all religious texts were hand written copies, of which there were relatively limited quantities in circulation.

Sacred texts of various religions

The following is a non-exhaustive list of links to specific religious texts which may be used for further, more in-depth study.

Bronze Age

- Pyramid Texts

- Coffin Texts

- Book of the Dead

- Book of Caverns

- Book of Gates

- Amduat

- Book of the Heavenly Cow

- Litany of Re

- Atenism: Great Hymn to the Aten

- Hymn to Enlil

- Kesh Temple Hymn

- Song of the hoe

- Innana Descent to the Underworld

- Epic of Gilgamesh

- Epic of Enmerkar

- Epic of Lugalbanda

Classical antiquity

- Etruscan religion

- Ancient Greece

- Aretalogy

- Argonautica

- Bibliotheca

- Derveni papyrus

- Ehoiai

- Homeric Hymns

- Iliad

- Odyssey

- Telegony

- The golden verses of Pythagoras

- Delphic maxims

- Theogony

- Works and Days

- Epic Cycle

- Theban Cycle

- Manichaeism

- The Gospel of Mani. Also known as The Living Gospel

- the Treasure of Life

- the Pragmateia (Greek: πραγματεία)

- The Book of Giants

- Fundamental Epistle

- Manichaean Psalter

- The Shabuhragan

- The Arzhang

- The Kephalaia (Greek: Κεφάλαια), "Discourses", found in Coptic translation.

- Orphism

- Orphic Poems

Ancient China

- Confucianism

- The Five Classics

- The Four Books

- The Thirteen Classics

- The Three Commentaries

Ethnic religions

- Bön (Tibetan folk religion): Bon Kangyur and Tengyur

- Old Norse Paganism: Edda

- Kiratism: The Mundhum of the Limbu ethnic group

- Qizilbash

- Buyruks of Qizilbash

- Fetevatnameh

- Samaritanism

- The Samaritan Torah

- Shabakism

- Shinto

- The Kojiki

- The Rikkokushi, which includes the Nihon Shoki and the Shoku Nihongi

- The Fudoki

- The Jinnō Shōtōki

- The Kujiki

Iranian

- Primary religious texts, that is, the Avesta collection:

- The Yasna, the primary liturgical collection, includes the Gathas.

- The Visperad, a collection of supplements to the Yasna.

- The Yashts, hymns in honor of the divinities.

- The Vendidad, describes the various forms of evil spirits and ways to confound them.

- shorter texts and prayers, the Yashts the five Nyaishes ("worship, praise"), the Sirozeh and the Afringans (blessings).

- There are some 60 secondary religious texts, none of which are considered scripture. The most important of these are:

- The Denkard (middle Persian, 'Acts of Religion'),

- The Bundahishn, (middle Persian, 'Primordial Creation')

- The Menog-i Khrad, (middle Persian, 'Spirit of Wisdom')

- The Arda Viraf Namak (middle Persian, 'The Book of Arda Viraf')

- The Sad-dar (modern Persian, 'Hundred Doors', or 'Hundred Chapters')

- The Rivayats, 15th-18th century correspondence on religious issues

- For general use by the laity:

- The Zend (lit. commentaries), various commentaries on and translations of the Avesta.

- The Khordeh Avesta, Zoroastrian prayer book for lay people from the Avesta.

- Kalâm-e Saranjâm

- The true core texts of the Yazidi religion that exist today are the hymns, known as qawls. Spurious examples of so-called "Yazidi religious texts" include the Yazidi Black Book and the Yazidi Book of Revelation, which were forged in the early 20th century

- Rasa'il al-hikmah (Epistles of Wisdom)

Indian

Hinduism

- The Four Vedas

- Rig Veda

- Sama Veda

- Yajur Veda

- Atharva Veda

- Samhitas (Mantras, Prayers)

- Brahmanas (Commentaries, Instructions)

- Aranyakas (Meditation, Rituals)

- Upanishads (Essence, Wisdom)

- Itihāsas

- Mahābhārata (including the Bhagavad Gita)

- Ramayana

- Puranas (List)

- Tantras

- Sutras (List)

- Stotras

- Ashtavakra Gita

- Gherand Samhita

- Gita Govinda

- Hatha Yoga Pradipika

- Yoga Vasistha

- In Purva Mimamsa

- In Vedanta (Uttar Mimamsa)

- In Yoga

- In Samkhya

- Samkhya Sutras of Kapila

- In Nyaya

- Nyāya Sūtras of Gautama

- In Vaisheshika

- Vaisheshika Sutras of Kanada

- In Vaishnavism

- Vaikhanasa Samhitas

- Pancaratra Samhitas

- Divyaprabandha

- In Saktism

- Sakta Tantras

- In Kashmir Saivism

- 64 Bhairavagamas

- 28 Shaiva Agamas

- Shiva Sutras of Vasugupta

- Vijnana Bhairava Tantra

- Pashupata Sutras of Lakulish

- Panchartha-bhashya of Kaundinya (a commentary on the Pashupata Sutras)

- Ganakarika

- Ratnatika of Bhasarvajna

- 28 Saiva Agamas

- Tirumurai (canon of 12 works)

- Meykandar Shastras (canon of 14 works)

- Krishna-karnamrita

- Chaitanya Bhagavata

- Chaitanya Charitamrita

- Prema-bhakti-candrika

- Hari-bhakti-vilasa

- In Lingayatism

- Siddhanta Shikhamani

- Vachana sahitya

- Mantra Gopya

- Shoonya Sampadane

- 28 Agamas

- Karana Hasuge

- Basava purana

- In Kabir Panth

- poems of Kabir

- In Dadu Panth

- poems of Dadu

Buddhism

- Theravada Buddhism

- The Tipitaka or Pāli Canon

- Vinaya Pitaka

- Sutta Pitaka

- Digha Nikaya, the "long" discourses

- Majjhima Nikaya, the "middle-length" discourses

- Samyutta Nikaya, the "connected" discourses

- Anguttara Nikaya, the "numerical" discourses

- Khuddaka Nikaya, the "minor collection"

- Abhidhamma Pitaka

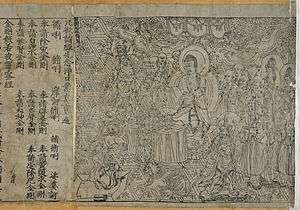

- East Asian Mahayana

- The Chinese Buddhist Mahayana sutras, including

- Diamond Sutra and the Heart Sutra

- Shurangama Sutra and its Shurangama Mantra

- Great Compassion Mantra

- Pure Land Buddhism

- Infinite Life Sutra

- Amitabha Sutra

- Contemplation Sutra

- other Pure Land Sutras

- Tiantai, Tendai, and Nichiren

- Shingon

Jainism

- Svetambara

- 11 Angas

- Secondary

- 12 Upangas, 4 Mula-sutras, 6 Cheda-sutras, 2 Culika-sutras, 10 Prakirnakas

- Secondary

- Samaysara

- Pravachanasara

- Niyamsara

- Pancastikayasara

- Karmaprabhrita, also called Satkhandagama

- Kashayaprabhrita

- Nonsectarian/Nonspecific

- Jina Vijaya

- Tattvartha Sutra

- GandhaHasti Mahabhashya (authoritative and oldest commentary on the Tattvartha Sutra)

- Four Anuyogas (they call them, the four vedas of jainism)

Sikhism

Secondary disputed scripture

- The Dasam Granth

Judaism

- Rabbinic Judaism

- See also: Rabbinic literature

- The Tanakh i.e. Hebrew Bible

- The Talmud

- The Midrash

- Kabbalah: Primary texts

- Zohar

- Early texts:

- Noam Elimelech (Elimelech of Lizhensk)

- Kedushat Levi (Levi Yitzchok of Berditchev)

- Foundational texts of various Hasidic sects:

- The Tanakh

- The Tanakh with several Jewish apocrypha

- Tanakh

- Jewish Science: Divine Healing in Judaism

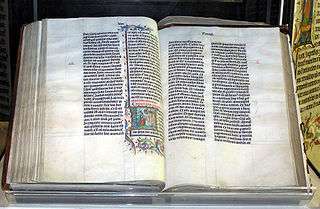

Christianity

Bible

The books of the Christian Bible differ by denomination.

- Common to the canons of all Christian denominations arising from proto-orthodox Christianity are the Old Testament of 39 protocanonical books and the New Testament of 27 books.

- Aside from Protestantism, at least 7 more books in the Old Testament, the deuterocanonical books.

- Catholicism defines only the above, for a total of 73 books, called the Canon of Trent (in versions of the Latin Vulgate, 3 Esdras, 4 Esdras, and the Prayer of Manasseh are included in an appendix, but considered non-canonical).

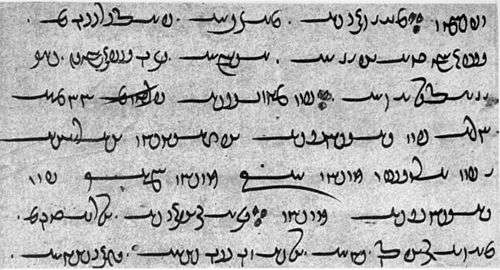

- For the Church of the East, this includes most of the deuterocanonical books of the Old Testament which are found in the Peshitta (The Syriac Version of the Bible). The New Testament in modern versions contains the 5 disputed books (2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, Jude, and Revelation) that were originally excluded.

- For Eastern Orthodoxy, this includes the anagignoskomena, which consist of the Catholic deuterocanon, plus 3 Maccabees, Psalm 151, the Prayer of Manasseh, and 3 Esdras; 4 Maccabees is considered to be canonical by the Georgian Orthodox Church.[29] Also, the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Old Testament, is authoritative.

- For Oriental Orthodoxy, the biblical canon differs in each Patriarchate.

- The Armenian Apostolic Orthodox Church has at various times included a variety of books in the New Testament which are not included in the canons of other traditions.

- The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (and its daughter, the Eritrean Orthodox Church) accept various books according to either of the Narrower or the Broader Canons but always include the entire Catholic deuterocanon, The Prayer of Manasseh, 3 Ezra, 4 Ezra, and The Book of Josippon. They may also include the Book of Jubilees, Book of Enoch, 1 Baruch, 4 Baruch, as well as 1, 2, and 3 Meqabyan (no relation to the Books of Maccabees). The New Testament contains the Sinodos, the Books of the Covenant, Clement, and the Didascalia.

- Some Syrian Churches, regardless of whether they are Eastern Catholic, Nestorian, Oriental or Eastern Orthodox, accept the Letter of Baruch as scripture.

- For most of Protestantism, this includes the 66-book canon - the Jewish Tanakh of 24 books divided differently (into 39 books) and the universal 27-book New Testament. Some denominations (e.g. Anglicanism) also include the 15 books of the biblical apocrypha between the Old Testament and the New Testament, for a total of 81 books.

- Some early Quakers also included the Epistle to the Laodiceans.[30]

- For Jehovah's Witnesses, the Bible (The New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures is their preferred translation.)

Additional and alternate scriptures

Some Christian denominations have additional or alternate holy scriptures, some with authoritativeness similar to the Old Testament and New Testament.

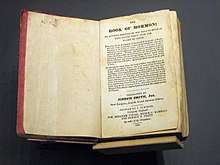

- Latter Day Saint movement (standard works) include:

- The Bible:

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) uses the LDS edition of the King James Bible for English-speaking members; other versions are used in non-English speaking countries.

- The Community of Christ (RLDS) uses the Joseph Smith Translation, which it calls the Inspired Version, as well as updated modern translations.

- The Book of Mormon

- The Doctrine and Covenants. There are significant differences in content and section numbering between the Doctrine and Covenants used by the Community of Christ (RLDS) and the LDS Church.

- The Pearl of Great Price is authoritative in the LDS Church, rejected by Community of Christ.

- Other, smaller branches of Latter Day Saints include other scriptures such as:

- The Book of the Law of the Lord used by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Strangite)

- The Word of the Lord and The Word of the Lord Brought to Mankind by an Angel used by (Fettingite) branches.

- (See also Biblical canon#Latter Day Saint canons.)

- The Bible:

- The Unification Church includes the Divine Principle in its holy scriptures.

- The Jewish–Christian gospels have been lost, so the scriptural canon of Jewish Christians outside of proto-orthodox Christianity is uncertain, beyond continued reliance on the Hebrew Bible.

- Gnostic Christianity rejected the narrative in Pauline Christianity that the arrival of Jesus had to do with the forgiveness of sins, and instead were concerned with illusion and enlightenment. Gnostic texts include Gnostic gospels about the life of Jesus, books attributed to various apostles, apocalyptic writings, and philosophical works. Though there is some overlap with some New Testament works, the rest were eventually considered heretical by Christian orthodoxy. Gnostics generally did not include the Old Testament as canon. They believed in two gods, one of which was Yahweh (generally considered evil), the author of the Hebrew Bible and god of the Jews, separate from a Supreme God who sent Jesus.

- The canon adopted by Marcion of Sinope included only the Gospel of Marcion and a set of Pauline epistles which overlap with the canon of orthodox Pauline Christianity. His gospel was a version of the Gospel of Luke that did not contain any references to the Old Testament.

- Cainites allied themselves with people who Yahweh of the Hebrew Bible oppressed, and apparently used the Gospel of Judas.

Doctrines and laws

Various Christian denominations have texts which define the doctrines of the group or set out laws which are considered binding. The groups consider these to range in permanence from unquestionable interpretations of divine revelations to human decisions made for convenience or elucidation which are subject to reconsideration.

- Seventh-day Adventists hold the writings of Ellen White are held to an elevated status, though not equal with the Bible, as she is considered to have been an inspired prophetess.

- The Christian Science textbook Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy, along with the Bible, serves as the permanent "impersonal pastor" of the Church of Christ, Scientist.

- Swedenborgianism is defined by the Biblical interpretations of Emanuel Swedenborg starting with Arcana Cœlestia

Liturgical books

Liturgical books are used to guide or script worship, and many are specific to a denomination.

- Catholic liturgical books

- Books of the clergy

- The Roman Missal (The pope, archbishops, bishops, priests and deacons editions)

- The Book of the Gospels (evangeliary/evangelion)

- The Lectionary

- Sacramentary (for bishops and priests)

- Pontifical (for bishops)

- Cæremoniale Episcoporum (for bishops)

- Breviary (Hours/Divine Office)

- Gradual (Roman gradual, antiphonal, cantatory)

- Liber Usualis (Book of Common Use/Gregorian chants)

- Roman Ritual (baptism, benedictions, blessings, burials, exorcisms, etc.)

- Roman Martyrology (saints/The blessed)

- Books of church attendants:

- Missal (pew cyclical editions)

- Missalette (pew seasonal editions)

- Hymnal (pew hymnbook editions)

- Books of the clergy

- Protestant liturgical books

- Lutheranism

- Evangelical Lutheran Hymn-Book (ELHB) 1912

- The Lutheran Hymnal (TLH) 1941

- Lutheran Book of Prayer (LBP) 1941

- Lutheran Service Book and Hymnal (SBH) 1958

- Lutheran Book of Worship (LBW) 1978

- Lutheran Worship (LW) 1982

- Evangelical Lutheran Worship (ELW) 2006

- Lutheran Service Book (LSB) 2006

- Numerous hymn, service and guide books (varies by church)

- Methodism

- The Sunday Service of the Methodists

- Book of Worship for Church and Home (1965)

- The Book of Hymns

- The United Methodist Hymnal (United Methodist Church)

- The United Methodist Book of Worship (1992) (United Methodist Church)

- Book of Discipline (United Methodist) (John Wesley-1784, United Methodist Church-2016)

- Numerous hymn, service and guide books (varies by church)

- Southern Baptists

- Baptist Hymnal

- Numerous hymn, service and guide books (varies by church)

- Lutheranism

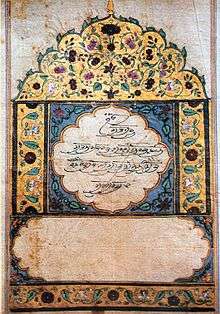

Islam

- The Quran (also referred to as Kuran, Koran, Qur’ān, Coran or al-Qur’ān) – Four books considered to be revealed and mentioned by name in the Quran are the Quran (revealed to Muhammad), Tawrat (revealed to Musa), the Zabur (revealed to Dawud) and the Injil (revealed to Isa)

- Hadith books (Sunni) (Kutub al-Sittah):

- Sahih Al-Bukhari

- Sahih Muslim

- Jami` at-Tirmidhi

- Sunan Abu Dawood

- Al-Sunan al-Sughra (Sunan an-Nasa'i)

- Sunan ibn Majah

- Other Hadith books

- Muwatta Imam Malik

- Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal

- Sunan al-Kubra

- The Meadows of the Righteous (Riyadh al-saliheen)

- Bulugh al-Maram

- Musannaf of Abd al-Razzaq

- Sunan al-Daraqutni

- Sahih Ibn Hibban

- Sunan al-Darimi

- Musnad al-Shafi'i

- Musnad Abu Hanifa

- Sahih ibn Khuzaima

- Musnad Tayalisi

- Musnad al-Bazzar

- Musnad Abi Ya'la

- Musnad Rahwayh

- Musnad ibn Humayd

- Musnad al-Firdous

- Tahdhib al-Athar

- Al-Mu'jam al-Awsat

- Al-Mu'jam as-Saghir

- Majma al-Zawa'id

- Kanz al-Ummal

- Shuab ul Iman

- Sharh Ma'anir Athar

- Sharh Mushkīlil Athar

- Silsilah Sahiha

- Mishkat al-Masabih

- Al-Adab al-Mufrad

- Sahih Hadith Kudsi

- Shama'il Muhammadiyah

- At-Targhib wat-Tarhib

- Shia Islam

- Hadith books (The Four Books): Kitab al-Kafi, Man La Yahduruhu al-Faqih Tahdhib al-Ahkam, Al-Istibsar.

- Other Hadith books (discourses of Prophet Muhammad and his household), like Bihar al-Anwar, Awalim al-Ulum; and Tafsirs, such as Tafsir al-Burhan

- Prayer books and Ziyarat such as Mafateh al Jinan and Kamel al Ziyarat.

- Books on biography of Prophet Muhammad. There are thousands of biographies written, though unlike the Hadith collections, they are usually not accepted as canonical religious texts. Some of the more authentic and famous of them are:

- Al-Sira Al-Nabawiyya.

- The Making of the last prophet by Ibn Ishaq

- The Life of Prophet Muhammad by Ibn Ishaq

- Sira Manzuma.

- al-Mawahib al-Ladunniya.

- al-Zurqani 'ala al-Mawahib.

- Sirah al-Halabiyya.

- I`lam al-Nubuwwa.

- Madarij al-Nubuwwa.

- Shawahid al-Nubuwwa.

- Nur al-Safir.

- Sharh al-Mawahib al-laduniyya.

- al-Durar fi ikhtisar al-maghazi was-siyar.

- Ashraf al-wasa'il ila faham al-Shama'il.

- Ghayat al-sul fi Khasa'is al-Rasul.

- Ithbat al-Nubuwwa.

- Nihaya al-Sul fi Khasa'is al-Rasul.

- Al Khasais-ul-Kubra, al-Khasa'is al-Sughra and Shama'il al-Sharifa.

- al-Durra al-Mudiyya.

- Alawites

- Quran

- Kitab al Majmu

- Other 114 canonical scriptures such as (Kitab ul Asus by an ancient prophet) and the other 113 scriptures were authored by imam Ali, imam Ja'far al-Sadiq, the 11th Bab Ibn Nusayr and the medieval sages of the sect such as Al-Khasibi.

- Mevlevi Order

- Alevism

- Quran

- Nahj al-Balagha

- Buyruks

- Makalat

- Vilayetname

- Akhiratnama

Pre-Columbian Americas

- Aztec religion

- The Borgia Group codices

- Maya religion

- The Popol Vuh

- the Dresden Codex

- the Madrid Codex

- the Paris Codex

New religious movements

- Ayyavazhi

- The Akilathirattu Ammanai

- The Arul Nool

- The writings of Franklin Albert Jones a.k.a. Adi Da Love-Ananda Samraj

- Aletheon

- The Companions of the True Dawn Horse

- The Dawn Horse Testament

- Gnosticon

- The Heart of the Adi Dam Revelation

- Not-Two IS Peace

- Pneumaton

- Transcendental Realism

- Aetherius Society

- The Nine Freedoms

- Bahá'í Faith: see Bahá'í literature

- Caodaism

- Kinh Thiên Đạo Và Thế Đạo (Prayers of the Heavenly and the Earthly Way)

- Pháp Chánh Truyền (The Religious Constitution of Caodaism)

- Tân Luật (The Canonical Codes)

- Thánh Ngôn Hiệp Tuyển (Compilation of Divine Messages)[31]

- Creativity Movement: The writings of Ben Klassen

- Nature's Eternal Religion

- White Man's Bible

- Salubrious Living

- Dudeism

- The Dude De Ching

- Duderonomy

- Freemasonry

- Book of Constitutions

- All Scriptures

- Jediism

- Aionomica

- Rammahgon

- Meher Baba

- God Speaks

- Discourses

- Meivazhi

- The four vedas of Meivazhi

- Āti mey utaya pūrana veētāntam

- Āntavarkal mānmiyam

- Eman pātar atipatu tiru meyññanak koral

- Eman pātar atipatu kotāyūtak kūr

- The four vedas of Meivazhi

- Raëlism: The writings of Raël aka Claude Vorilhon

- Intelligent Design: Message from the Designers

- Sensual Meditation

- Yes to Human Cloning

- Rastafari movement

- The Bible (Ethiopian Orthodox canon)

- the Holy Piby

- the Kebra Nagast

- The speeches and writings of Haile Selassie I (including his autobiography My Life and Ethiopia's Progress)

- Royal Parchment Scroll of Black Supremacy

- Science of Mind

- The Science of Mind by Ernest Holmes

- Scientology

- Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health

- List of Scientology texts

- Tenrikyo

- The Ofudesaki

- The Mikagura-uta

- The Osashizu

- Thelema

- The Holy Books of Thelema, especially The Book of the Law

- Unarius Academy of Science

- The Pulse of Creation Series

- The Infinite Concept of Cosmic Creation

- Wicca

- Book of Shadows

- Charge of the Goddess

- Threefold Law

- Wiccan Rede

References

- Charles Elster (2003). "Authority, Performance, and Interpretation in Religious Reading: Critical Issues of Intercultural Communication and Multiple Literacies". Journal of Literacy Research. 35 (1): 667–670., Quote: "religious texts serve two important regulatory functions: on the group level, they regulate liturgical ritual and systems of law; at the individual level, they (seek to) regulate ethical conduct and direct spiritual aspirations."

- Eugene Nida (1994). "The Sociolinguistics of Translating Canonical Religious Texts". TTR: Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction. Érudit: Université de Montréal. 7 (1): 195–197., Quote: "The phrase "religious texts" may be understood in two quite different senses: (1) texts that discuss historical or present-day religious beliefs and practices of a believing community and (2) texts that are crucial in giving rise to a believing community."

- Ricoeur, Paul (1974). "Philosophy and Religious Language". The Journal of Religion. University of Chicago Press. 54 (1): 71–85. doi:10.1086/486374.

- Lee Martin McDonald; James H. Charlesworth (5 April 2012). 'Noncanonical' Religious Texts in Early Judaism and Early Christianity. A&C Black. pp. 1–5, 18–19, 24–25, 32–34. ISBN 978-0-567-12419-7.

- Charles Elster (2003). "Authority, Performance, and Interpretation in Religious Reading: Critical Issues of Intercultural Communication and Multiple Literacies". Journal of Literacy Research. 35 (1): 669–670.

- John Goldingay (2004). Models for Scripture. Clements Publishing Group. pp. 183–190. ISBN 978-1-894667-41-8.

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (2009). Scripture. Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Wilfred Cantwell Smith (1994). What is Scripture?: A Comparative Approach. Fortress Press. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-1-4514-2015-9.

- William A. Graham (1993). Beyond the Written Word: Oral Aspects of Scripture in the History of Religion. Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-0-521-44820-8.

- Eugene Nida (1994). "The Sociolinguistics of Translating Canonical Religious Texts". 7 (1): 194–195. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Thomas B. Coburn (1984). ""Scripture" in India: Towards a Typology of the Word in Hindu Life". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. Oxford University Press. 52 (3): 435–459. doi:10.1093/jaarel/52.3.435. JSTOR 1464202.

- William A. Graham (1993). Beyond the Written Word: Oral Aspects of Scripture in the History of Religion. Cambridge University Press. pp. ix, 5–9. ISBN 978-0-521-44820-8.

- Carroll Stuhlmueller (1958). "The Influence of Oral Tradition Upon Exegesis and the Senses of Scripture". The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 20 (3): 299–302. JSTOR 43710550.

- Peter Beal (2008). A Dictionary of English Manuscript Terminology: 1450 to 2000. Oxford University Press. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-19-926544-2.

- "Scriptures". The World Encyclopedia. Oxford University Press. 2004. ISBN 978-0-19-954609-1.

- John Bowker (2000). "Scripture". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280094-7.

- Juan Carlos Ossandón Widow (2018). The Origins of the Canon of the Hebrew Bible. BRILL Academic. pp. 22–27. ISBN 978-90-04-38161-2.

- Gerbern Oegema (2012). Lee Martin McDonald and James H. Charlesworth (ed.). 'Noncanonical' Religious Texts in Early Judaism and Early Christianity. A&C Black. pp. 18–23 with footnotes. ISBN 978-0-567-12419-7.

- Edmon L. Gallagher; John D. Meade (2017). The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity: Texts and Analysis. Oxford University Press. pp. xii–xiii. ISBN 978-0-19-879249-9.

- Kramer, Samuel (1942). "The Oldest Literary Catalogue: A Sumerian List of Literary Compositions Compiled about 2000 B.C.". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 88 (88): 10–19. doi:10.2307/1355474. JSTOR 1355474.

- Sanders, Seth (2002). "Old Light on Moses' Shining Face". Vetus Testamentum. 52 (3): 400–406. doi:10.1163/156853302760197520.

- Enheduanna; Meador, Betty De Shong (2009-08-01). Princess, priestess, poet: the Sumerian temple hymns of Enheduanna. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292719323.

- Stephanie Dalley (2000). Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Oxford University Press. pp. 41–45. ISBN 978-0-19-953836-2.

- George, Andrew (2002-12-31). The Epic of Gilgamesh: The Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian. Penguin. ISBN 9780140449198.

- Sagarika Dutt (2006). India in a Globalized World. Manchester University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-84779-607-3

- "The Yahwist". Contradictions in the Bible. 2012-12-23. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- Jaffee, Martin S. (2001-04-19). Torah in the Mouth: Writing and Oral Tradition in Palestinian Judaism 200 BCE-400 CE. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198032236.

- "The History Guide". www.historyguide.org. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- Eastern Orthodox also generally divide Baruch and Letter of Jeremiah into two books instead of one. The enumeration of the Books of Ezra is different in many Orthodox Bibles, as it is in all others: see Wikipedia's article on the naming conventions of the Books of Esdras.

- Angell, Stephen W (2015), "Renegade Oxonian: Samuel Fisher's Importance in Formulating a Quaker Understanding of Scripture", in Angell, Stephen W; Dandelion, Pink (eds.), Early Quakers and Their Theological Thought 1647–1723, Cambridge University Press, pp. 137–154, doi:10.1017/cbo9781107279575.010, ISBN 9781107279575

- "Caodaism In A Nutshell".

- "chondogyo.or.kr". Archived from the original on February 18, 2005.

- "Sacred Scripture (Kyoten) - KONKOKYO".

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: religious text |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Religious texts. |