Roman Missal

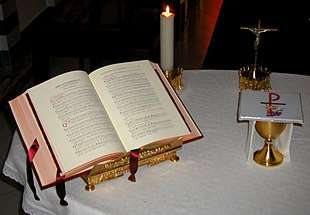

The Roman Missal (Latin: Missale Romanum) is the liturgical book that contains the texts and rubrics for the celebration of the Mass in the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church.

History

Missals before the Council of Trent

Before the high Middle Ages, several books were used at Mass: a Sacramentary with the prayers, one or more books for the Scriptural readings, and one or more books for the antiphons and other chants. Gradually, manuscripts came into being that incorporated parts of more than one of these books, leading finally to versions that were complete in themselves. Such a book was referred to as a Missale Plenum (English: "Full Missal").

In 1223 Saint Francis of Assisi instructed his friars to adopt the form that was in use at the Papal Court (Rule, chapter 3). They adapted this missal further to the needs of their largely itinerant apostolate. Pope Gregory IX considered, but did not put into effect, the idea of extending this missal, as revised by the Franciscans, to the whole Western Church; and in 1277 Pope Nicholas III ordered it to be accepted in all churches in the city of Rome. Its use spread throughout Europe, especially after the invention of the printing press; but the editors introduced variations of their own choosing, some of them substantial. Printing also favoured the spread of other liturgical texts of less certain orthodoxy. The Council of Trent determined that an end must be put to the resulting disparities.

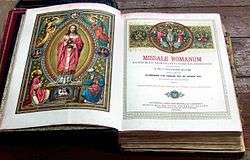

The first printed Missale Romanum (Roman Missal), containing the Ordo Missalis secundum consuetudinem Curiae Romanae (Order of the Missal in accordance with the custom of the Roman Curia), was produced in Milan in 1474.[1] Almost a whole century passed before the appearance of an edition officially published by order of the Holy See. During that interval, the 1474 Milanese edition was followed by at least 14 other editions: 10 printed in Venice, 3 in Paris, 1 in Lyon.[2] For lack of a controlling authority, these editions differ, sometimes considerably.[3]

Annotations in the hand of Cardinal Gugliemo Sirleto in a copy of the 1494 Venetian edition[4] show that it was used for drawing up the 1570 official edition of Pope Pius V. In substance, this 1494 text is identical with that of the 1474 Milanese edition.[3]

From the Council of Trent to the Second Vatican Council

Implementing the decision of the Council of Trent, Pope Pius V promulgated, in the Apostolic Constitution Quo primum of 14 July 1570, an edition of the Roman Missal that was to be in obligatory use throughout the Latin Church except where there was another liturgical rite that could be proven to have been in use for at least two centuries.

Some corrections to Pope Pius V's text proved necessary, and Pope Clement VIII replaced it with a new typical edition of the Roman Missal on 7 July 1604. (In this context, the word "typical" means that the text is the one to which all other printings must conform.) A further revised typical edition was promulgated by Pope Urban VIII on 2 September 1634.

Beginning in the late seventeenth century, France and neighbouring areas saw a flurry of independent missals published by bishops influenced by Jansenism and Gallicanism. This ended when Bishop Pierre-Louis Parisis of Langres and Abbot Guéranger initiated in the nineteenth century a campaign to return to the Roman Missal. Pope Leo XIII then took the opportunity to issue in 1884 a new typical edition that took account of all the changes introduced since the time of Pope Urban VIII. Pope Pius X also undertook a revision of the Roman Missal, which was published and declared typical by his successor Pope Benedict XV on 25 July 1920.

.jpg)

Though Pope Pius X's revision made few corrections, omissions, and additions to the text of the prayers in the Roman Missal, there were major changes in the rubrics, changes which were not incorporated in the section entitled "Rubricae generales", but were instead printed as an additional section under the heading "Additiones et variationes in rubricis Missalis."

In contrast, the revision by Pope Pius XII, though limited to the liturgy of only five days of the Church's year, was much bolder, requiring changes even to canon law, which until then had prescribed that, with the exception of Midnight Mass for Christmas, Mass should not begin more than one hour before dawn or later than one hour after midday. In the part of the Missal thus thoroughly revised, he anticipated some of the changes affecting all days of the year after the Second Vatican Council. These novelties included the first official introduction of the vernacular language into the liturgy for renewal of baptismal promises within the Easter Vigil celebration.[5][6]

Pope Pius XII issued no new typical edition of the Roman Missal, but authorized printers to replace the earlier texts for Palm Sunday, Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and the Easter Vigil with those that he began to introduce in 1951 and that he made universally obligatory in 1955.[7] The Pope also removed from the Vigil of Pentecost the series of six Old Testament readings, with their accompanying Tracts and Collects, but these continued to be printed until 1962.

Acceding to the wishes of many of the bishops, Pope Pius XII judged it expedient also to reduce the rubrics of the missal to a simpler form, a simplification enacted by a decree of the Sacred Congregation of Rites of 23 March 1955. The changes this made in the General Roman Calendar are indicated in General Roman Calendar of Pope Pius XII.

In the following year, 1956, while preparatory studies were being conducted for a general liturgical reform, Pope Pius XII surveyed the opinions of the bishops on the liturgical improvement of the Roman breviary. After duly weighing the answers of the bishops, he judged that it was time to address the need for a general and systematic revision of the rubrics of the breviary and missal. This question he referred to the special committee of experts appointed to study the general liturgical reform.

His successor, Pope John XXIII, issued a new typical edition of the Roman Missal in 1962. This incorporated the revised Code of Rubrics which Pope Pius XII's commission had prepared, and which Pope John XXIII had made obligatory with effect from 1 January 1961. In the Missal, this Code of Rubrics replaced two of the documents in the 1920 edition; and the Pope's motu proprio Rubricarum instructum took the place of the superseded Apostolic constitution Divino afflatu of Pope Pius X.

Other notable revisions were the omission of the adjective "perfidis" in the Good Friday Prayer for the Jews and the insertion of the name of Saint Joseph into the Canon (or Eucharistic Prayer) of the Mass.

Revision of the Missal following the Second Vatican Council

_001.jpg)

In 1965 and 1967 some changes were officially introduced into the Mass of the Roman Rite in the wake of Sacrosanctum Concilium, but no new edition of the Roman Missal had been produced to incorporate them. They were reflected in the provisional vernacular translations produced in various countries when the language of the people began to be used in addition to Latin. References sometimes met in an English-language context to "the 1965 Missal" concern these temporary vernacular productions, not the Roman Missal itself. Some countries that had the same language used different translations and varied in the amount of vernacular admitted.

A new edition of the Roman Missal was promulgated by Pope Paul VI with the apostolic constitution Missale Romanum of 3 April 1969. The full text of the revised Missal was not published until the following year, and full vernacular translations appeared some years later, but parts of the Missal in Latin were already available since 1964 in non-definitive form, and provisional translations appeared without delay.

In his apostolic constitution, Pope Paul made particular mention of the following significant changes that he had made in the Roman Missal:

- To the single Eucharistic Prayer of the previous edition (which, with minor alterations, was preserved as the "First Eucharistic Prayer or Roman Canon") he added three alternative Eucharistic Prayers, increasing also the number of prefaces.

- The rites of the Order of Mass (in Latin, Ordo Missae)—that is, the largely unvarying part of the liturgy—were "simplified, while due care is taken to preserve their substance." "Elements which, with the passage of time, came to be duplicated, or were added with but little advantage" were eliminated, especially in the rites for the preparation of the bread and wine, the breaking of the bread, and communion.

- "'Other elements which have suffered injury through accidents of history are now to be restored to the earlier norm of the Holy Fathers' (Sacrosanctum Concilium, art. 50), for example, the homily (see Sacrosanctum Concilium, art. 52) and the 'common prayer' or 'prayer of the faithful' (see Sacrosanctum Concilium, art. 53)."[8] Paul VI also added the option of "a penitential rite or act of reconciliation with God and the brothers, at the beginning of the Mass," though this was neither an ancient part of the Introductory Rite nor mentioned in Sacrosanctum Concilium.[9]

- He greatly increased the proportion of the Bible read at Mass. Even before Pius XII reduced the proportion further, only 1% of the Old Testament and 16.5% of the New Testament was read at Mass. In Pope Paul's revision, 13.5% of the Old Testament and 71.5% of the New Testament are read.[10] He was able to do this by having more readings at Mass and introducing a three-year cycle of readings on Sundays and a two-year cycle on weekdays.

In addition to these changes, the Pope noted that his revision considerably modified other sections of the Missal, such as the Proper of Seasons, the Proper of Saints, the Common of Saints, the Ritual Masses, and the Votive Masses, adding: "In all of these changes, particular care has been taken with the prayers: not only has their number been increased, so that the new texts might better correspond to new needs, but also their text has been restored on the testimony of the most ancient evidences."

Editions of the Vatican II Roman Missal

In 1970, the first typical edition of the Roman Missal (in Latin) bearing the title Missale Romanum ex decreto Sacrosancti Oecumenici Concilii Vaticani II instauratum was published, after being formally promulgated by Pope Paul VI in the previous year. A reprint that corrected misprints appeared in 1971. A second typical edition, with minor changes, followed in 1975. In 2000, Pope John Paul II approved a third typical edition, which appeared in 2002. This third edition added feasts, especially of some recently canonized saints, new prefaces of the Eucharistic Prayers, and additional Masses and prayers for various needs, and it revised and amplified the General Instruction of the Roman Missal.[11]

In 2008, under Pope Benedict XVI, an emended reprint of the third edition was issued, correcting misprints and some other mistakes (such as the insertion at the beginning of the Apostles' Creed of "unum", as in the Nicene Creed). A supplement gives celebrations, such as that of Saint Pio of Pietrelcina, added to the General Roman Calendar after the initial printing of the 2002 typical edition.

Three alterations required personal approval by Pope Benedict XVI:

- A change in the order in which a bishop celebrating Mass outside his own diocese mentions the local bishop and himself

- Omission from the Roman Missal of the special Eucharistic Prayers for Masses with Children (which were not thereby abolished)

- The addition of three alternatives to the standard dismissal at the end of Mass, Ite, missa est (Go forth, the Mass is ended):

- Ite ad Evangelium Domini annuntiandum (Go and announce the Gospel of the Lord)

- Ite in pace, glorificando vita vestra Dominum (Go in peace, glorifying the Lord by your life)

- Ite in pace (Go in peace)[12]

Pope John XXIII's 1962 edition of the Roman Missal began a period of aesthetic preference for a reduced number of illustrations in black and white instead of the many brightly coloured pictures previously included. The first post-Vatican II editions, both in the original Latin and in translation, continued that tendency. The first Latin edition (1970) had in all 12 black-and-white woodcut illustrations by Gian Luigi Uboldi. The 1974 English translation adopted by the United States episcopal conference appear in several printings. Our Sunday Visitor printed it with further illustrations by Uboldi, while the printing by Catholic Book Publishing had woodcuts in colour. The German editions of 1975 and 1984 had no illustrations, thus emphasizing the clarity and beauty of the typography. The French editions of 1974 and 1978 were also without illustrations, while the Italian editions of 1973 and 1983 contained both reproductions of miniatures in an 11th-century manuscript and stylized figures whose appropriateness is doubted by the author of a study on the subject, who also makes a similar observation about the illustrations in the Spanish editions of 1978 and 1988. The minimalist presentation in these editions contrasts strongly with the opulence of United States editions of the period between 2005 and 2011 with their many full-colour reproductions of paintings and other works of art.[13]

The first vernacular version of the third edition (2002) of the Vatican II Roman Missal to be published was that in Greek. It appeared in 2006.[14] The English translation. taking into account the 2008 changes, came into use in 2011. Translations into some other languages took longer: that into Italian was decided on by the Episcopal Conference of Italy at its November 2018 meeting and was confirmed by the Holy See in the following year, as announced by the conference's president at its 22 May 2019 meeting. It replaces the 1983 Italian translation of the 1975 second Latin edition. The new text includes changes to the Italian Lord's Prayer and Gloria. In the Lord's Prayer, e non c'indurre in tentazione ("and lead us not into temptation") becomes non abbandonarci alla tentazione ("do not abandon us to temptation") and come noi li rimettiamo ai nostri debitori ("as we forgive our debtors") becomes come anche noi li rimettiamo ai nostri debitori ("as we too forgive our debtors"). In the Gloria pace in terra agli uomini di buona volontà ("peace on earth to people of good will") becomes pace in terra agli uomini, amati dal Signore ("peace on earth to people, who are loved by the Lord").[15][16][17][18][19][20]

Continued use of earlier editions

In his motu proprio Summorum Pontificum of 7 July 2007, Pope Benedict XVI stated that the 1962 edition of the Roman Missal was never juridically abrogated and that it may be freely used by any priest of the Latin Rite when celebrating Mass "without a congregation".[21] Use of the 1962 edition at Mass with a congregation is allowed, with the permission of the priest in charge of a church, for stable groups attached to this earlier form of the Roman Rite, provided that the priest using it is "qualified to do so and not juridically impeded" (as for instance by suspension). Accordingly, many dioceses schedule regular Masses celebrated using the 1962 edition, which is also used habitually by priests of traditionalist fraternities in full communion with the Holy See such as the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter, the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest, the Personal Apostolic Administration of Saint John Mary Vianney, the Canons Regular of Saint John Cantius, and the Canons Regular of the Mother of God [22] in Lagrasse, France.

Of groups in dispute with the Holy See, the Society of St. Pius X uses the 1962 Missal, and smaller groups such as the Society of St. Pius V and the Congregation of Mary Immaculate Queen use earlier editions.

For information on the calendars included in pre-1970 editions (a small part of the full Missal), see General Roman Calendar of 1960, General Roman Calendar of Pope Pius XII, General Roman Calendar of 1954, and Tridentine Calendar.

Official English translations

The International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL) prepared an English translation of the 1970 Roman Missal, which was approved by the individual English-speaking episcopal conferences and, after being reviewed by the Holy See, was put into effect, beginning with the United States in 1973.

The authority for the episcopal conferences, with the consent of the Holy See, to decide on such translations was granted by the Second Vatican Council.[23][24]

ICEL prepared a greatly altered English translation, and presented it for the consent of the Holy See in 1998. The Holy See withheld its consent and informed ICEL that the Latin text of the Missal, which must be the basis of translations into other languages, was being revised, making irrelevant a translation based on what would no longer be the official text of the Roman Missal.

On 28 March 2001, the Holy See issued the Instruction Liturgiam Authenticam, which included the requirement that in translations of the liturgical texts from the official Latin originals, "the original text, insofar as possible, must be translated integrally and in the most exact manner, without omissions or additions in terms of their content, and without paraphrases or glosses. Any adaptation to the characteristics or the nature of the various vernacular languages is to be sober and discreet." This was a departure from the principle of dynamic equivalence promoted in ICEL translations after the Second Vatican Council.

In the following year, the third typical edition of the revised Roman Missal in Latin, which had already been promulgated in 2000, was released. These two texts made clear the need for a new official English translation of the Roman Missal, particularly because the previous one was at some points an adaptation rather than strictly a translation. An example is the rendering of the response "Et cum spiritu tuo" (literally, "And with your spirit") as "And also with you." Accordingly, the International Commission for English in the Liturgy prepared, with some hesitancy on the part of the bishops, a new English translation of the Roman Missal, the completed form of which received the approval of the Holy See in April 2010.[25]

On 19 July 2001, the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments established an international committee of English-speaking bishops, called the Vox Clara Committee, "to advise that Dicastery in its responsibilities related to the translation of liturgical texts in the English language and to strengthen effective cooperation with the Conferences of Bishops".[26] On the occasion of the meeting of the committee in Rome in April 2002, Pope John Paul II sent them a message emphasizing that "fidelity to the rites and texts of the Liturgy is of paramount importance for the Church and Christian life" and charging the committee to ensure that "the texts of the Roman Rite are accurately translated in accordance with the norms of the Instruction Liturgiam authenticam".[27] Liturgiam authenticam also took from the Bishops' conferences the power to make its own translations and instituted a papal commission, Vox Clara, to revise the Bishops' work. In 2008 it made an estimated 10,000 changes to the ICEL's proposed text. By 2017 Pope Francis had formed a commission to review and evaluate Liturgiam authenticam.[28][29]

The work of making a new translation of the Roman Missal was completed in time to enable the national episcopal conference in most English-speaking countries to put it into use from the first Sunday of Advent (27 November) 2011.

As well as translating "Et cum spiritu tuo" as "And with your spirit", which some scholars suggest refers to the gift of the Holy Spirit the priest received at ordination,[30] in the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed "consubstantial with the Father" was used as a translation of "consubstantialem Patri" (in Greek "ὁμοούσιον τῷ Πατρί"),[31] instead of "of one Being with the Father" (or, in the United States only, "one in Being with the Father"), and the Latin phrase qui pro vobis et pro multis effundetur in remissionem peccatorum, formerly translated as "It will be shed for you and for all so that sins may be forgiven," was translated literally as "which will be poured out for you and for many for the forgiveness of sins" (see Pro multis).[32]

This new official translation of the entire Order of Mass is available on the website of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops,[33] which also provides a comparison between the new text of the people's parts and that hitherto in use in the United States (where the version of the Nicene Creed was slightly different from that in other English-speaking countries).[34]

Pope Benedict XVI remarked: "Many will find it hard to adjust to unfamiliar texts after nearly forty years of continuous use of the previous translation. The change will need to be introduced with due sensitivity, and the opportunity for catechesis that it presents will need to be firmly grasped. I pray that in this way any risk of confusion or bewilderment will be averted, and the change will serve instead as a springboard for a renewal and a deepening of Eucharistic devotion all over the English-speaking world."[35]

The plan to introduce the new English translation of the missal was not without critics. Over 22,000 electronic signatures, some of them anonymous, were collected on a web petition to ask the Bishops, Cardinals and the Pope to reconsider the new translation.[36] At the time there was open dissent from one parish in Seattle.[37]

The Southern African Catholic Bishops' Conference (Botswana, South Africa, Swaziland) put into effect the changes in the people's parts of the revised English translation of the Order of Mass[38] from 28 November 2008, when the Missal as a whole was not yet available. Protests were voiced on grounds of content[39][40][41] and because it meant that Southern Africa was thus out of line with other English-speaking countries.[42] One bishop claimed that the English-speaking conferences should have withstood the Holy See's insistence on a more literal translation.[43] However, when in February 2009 the Holy See declared that the change should have awaited completion of work on the Missal, the bishops conference appealed, with the result that those parishes that had adopted the new translation were directed to continue using it, while those that had not were told to await further instructions before doing so.[44]

In view of the foreseen opposition to making changes, the various English-speaking episcopal conferences arranged catechesis on the Mass and the Missal, and made information available also on the Internet.[45] Other initiatives included publication by the conservative,[46] United States-based Catholic News Agency of a series of ten articles on the revised translation.[47]

Pope Francis' approach

On 9 September 2017 Pope Francis issued the motu proprio Magnum Principium ("The Great Principle") which allowed local bishops' conferences more authority over translation of liturgical documents. The motu proprio "grants the episcopal conferences the faculty to judge the worth and coherence of one or another phrase in the translations from the original."[48] The role of the Vatican is also modified in accord with the decree of Vatican II,[49] to confirming texts already prepared by bishops' conferences, rather than "recognition" in the strict sense of Canon Law no. 838.[50]

See also

References

- Catholic Church (1899). Missale romanum Mediolani, 1474 (in Latin). unknown library. [Printed for the Society by Harrison and sons].

- Manlio Sodi and Achille Maria Triacca, Missale Romanum: Editio Princeps (1570) (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1998), p. XV

- Celiński, Łukasz. "Per una rilettura della storia della formazione e dello sviluppo del Messale Romano. Il caso del Messale di Clemente V." Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Missale secundum morem Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae (Missal in line with the use of the Holy Roman Church)

- Thomas A. Droleskey. "Presaging a Revolution". ChristorChaos.com. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Rev. Francesco Ricossa. "Liturgical Revolution". TraditionalMass.org. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Decree Maxima redemptionis nostrae mysteria Archived 12 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine (Acta Apostolicae Sedis 47 (1955) 838-847

- Missale Romanum. The internal references to Sacrosanctum Concilium are to the Constitution of the Second Vatican Council on the Sacred Liturgy.

- "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Confiteor". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- Felix Just, S.J. (2 January 2009). "Lectionary Statistics". Catholic-resources.org. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Archived from the original on 20 December 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- A full account of the corrections, additions and emendations is given on pages 367-387 of the July–August 2008 issue of Notitiae, the bulletin of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. Some much less detailed information may also be found in an interview given by Cardinal Francis Arinze.

- Ralf van Bühren, "Die Bildausstattung des „Missale Romanum“ nach dem Zweiten Vatikanischen Konzil (1962−1965)", in Hans Peter Neuheuser (editor), Liturgische Bücher in der Kulturgeschichte EuropasHans Peter Neuheuser Hans Peter Neuheuser Hans Peter Neuheuser Hans Peter Neuheuser Hans Peter Neuheuser Hans Peter Neuheuser Hans Peter Neuheuser Hans Peter Neuheuser Hans Peter Neuheuser (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2018), pp. 173–181

- Επιστολή της Ι. Συνόδου Ιεραρχίας προς τους Ιερείς (Letter of the Greek Episcopal Conference to Priests 7 September 2006

- Gambassi, Giacomo (22 May 2019). "Liturgia. Via libera del Papa alla nuova traduzione italiana del Messale" [Liturgy. Pope okays new Italian translation of the Missal] (in Italian). Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- uCatholic (3 June 2019). "Pope Francis Approves Changes to Lord's Prayer & Gloria of Italian Missal". uCatholic. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "Pope Francis Approves Updated Translation of Lord's Prayer: 'Do Not Let Us Fall Into Temptation'". CBN News. 4 June 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- enquiries@thetablet.co.uk, The Tablet-w. "'Lead us not into temptation' falls out of Lord's Prayer". The Tablet. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- uCatholic (3 June 2019). "Pope Francis Approves Changes to Lord's Prayer & Gloria of Italian Missal". uCatholic. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "Francis approves revised translation of Italian Missal- La Croix International". international.la-croix.com. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum on the "Roman liturgy prior to the reform of 1970" (July 7, 2007) | BENEDICT XVI". w2.vatican.va. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "Accueil - Abbaye". Abbaye (in French). Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- "It is for the competent territorial ecclesiastical authority mentioned in Art. 22, 2, to decide whether, and to what extent, the vernacular language is to be used; their decrees are to be approved, that is, confirmed, by the Apostolic See. And, whenever it seems to be called for, this authority is to consult with bishops of neighbouring regions which have the same language. Translations from the Latin text into the mother tongue intended for use in the liturgy must be approved by the competent territorial ecclesiastical authority mentioned above" (Sacrosanctum Concilium, Second Vatican Council, Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, art. 36, 3-4).

- "Code of Canon Law, canon 455". Intratext.com. 4 May 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "News". Icelweb.org. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "Press Release". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- Helen Hull Hitchcock. "Vox Clara committee to assure fidelity, accuracy". Adoremusweb.org. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- "Revisiting Liturgiam Authenticam, Part I: Vox Clara | Commonweal Magazine". www.commonwealmagazine.org. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- "Revisiting 'Liturgiam Authenticam': An Update | Commonweal Magazine". www.commonwealmagazine.org. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Notes on the New Translation of the Missale Romanum, editio typica tertia. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Archived from the original on 26 November 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". In the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Six Questions on the Translation of Pro Multis as “For Many”. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Archived from the original on 6 December 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "Order of Mass" (PDF). Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "Changes in the People's Parts". Usccb.org. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "To Members and Consultors of the Vox Clara Committee, 28 April 2010". Vatican.va. 28 April 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "What If We Just Said Wait?". WhatIfWeJustSaidWait.org. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "St. Leo Parish Council" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- "A pastoral response to the faithful with regard to the new English Language Mass translations :: bisdomoudtshoorn.org ::". 8 March 2009. Archived from the original on 8 March 2009. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- Gunther Simmermacher. "Liturgical Anger". Scross.co.za. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Fr John Conversett MCCJ. "Letter". Scross.co.za. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Coyle IHM. Mass translations: A missed opportunity

- Risi, Edward (3 February 2009). "Pastoral Response to the New English Translation Text for Mass". South African Bishops Conference. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- Bishop Dowling. "Letter". Scross.co.za. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- Brennan, Vincent (5 March 2009). "Clarification on the Implementation of the New English Mass Translation in South Africa". Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- England and Wales; Australia; New Zealand; Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine United States.

- Winters, Michael (22 June 2010). "When Is News Not News? When It's Made Up". America Magazine. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "Preparing the way for the Roman Missal – 3rd Edition". CatholicNewsAgency.com. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- McElwee, Joshua J. (22 October 2017). "Francis corrects Sarah: Liturgical translations not to be 'imposed' from Vatican". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "Sacrosanctum Concilium, 39,40". 4 December 1963. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- Carstens, Christopher (4 January 2018). "What is the current status of the translation document Liturgiam Authenticam?". Adoremus.

Further reading

- Goldhead Group, The (2010). New Translation of the English Roman Missal: A Comprehensive Guide and Explanation. Minneapolis: Lulu. ISBN 978-0-557-86206-1. An exploration of the changes to the English Roman Missal affecting English speaking Catholics as of the First Sunday of Advent in 2011.

External links

Online texts of editions of the Roman Missal

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Missals. |

Full texts of the Missale Romanum

- 2008 Roman Missal in English translation (2011)

- 2002 third typical Vatican II edition of the Roman Missal

- 1962 typical edition of the Roman Missal scanned in black and white (musicasacra.com)

- 1920 typical edition of the Roman Missal, with feasts updated to the late 1920s (musicasacra.com)

- Missale Romanum published by Pustet, 1894 (1884 typical edition)

- Roman Missal, published by Pustet, 1862 (1634 typical edition, updated to 1862)

- List of links to on-line reproductions of Latin manuscripts and printed editions from c. 1100 to 2002 and old translations

Texts of Roman Rite missals earlier than the 1570 Roman Missal

Partial texts

- Order of Mass (2011 translation) as a web page and downloadable in ePub and Kindle formats

- Ordo Missae of the 1962 Roman Missal with an English translation and audio of the (Latin) text

- General Instruction of the Roman Missal of 2002 English translation, but with adaptations for Australia

- General Instruction of the Roman Missal of 2002 English translation, but with adaptations for the United States of America

- General Instruction of the Roman Missal of 2002 English translation, but with adaptations for England and Wales

- General Instruction of the Roman Missal of 2002 Latin text, free from adaptations for particular countries

- Promulgation of the Roman Missal Revised by Decree of the Second Vatican Council, 1969

- English translation of the Rubrics of the 1962 Roman Missal