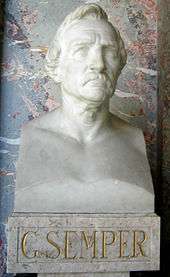

Gottfried Semper

Gottfried Semper (German: [ˌɡɔtfriːt ˈzɛmpɐ]; 29 November 1803 – 15 May 1879) was a German architect, art critic, and professor of architecture, who designed and built the Semper Opera House in Dresden between 1838 and 1841. In 1849 he took part in the May Uprising in Dresden and was put on the government's wanted list. Semper fled first to Zürich and later to London. Later he returned to Germany after the 1862 amnesty granted to the revolutionaries.

Gottfried Semper | |

|---|---|

-Portrait-Portr_10869.tif_(cropped).jpg) Gottfried Semper | |

| Born | 29 November 1803 |

| Died | 15 May 1879 (aged 75) |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | Semper Opera House |

Semper wrote extensively about the origins of architecture, especially in his book The Four Elements of Architecture from 1851, and he was one of the major figures in the controversy surrounding the polychrome architectural style of ancient Greece. Semper designed works at all scales, from major urban interventions like the re-design of the Ringstraße in Vienna, to a baton for Richard Wagner.[1] His unrealised design for an opera house in Munich was, without permission, adapted by Wagner for the Bayreuth Festspielhaus.

Life

Early life (to 1834)

Semper was born into a well-to-do industrialist family in Altona. The fifth of eight children, he attended the Gelehrtenschule des Johanneums in Hamburg before starting his university education at Göttingen in 1823, where he studied historiography and mathematics. He subsequently studied architecture in 1825 at the University of Munich under Friedrich von Gärtner. In 1826, Semper travelled to Paris in order to work for the architect Franz Christian Gau, and he was present when the July Revolution of 1830 broke out. Between 1830 and 1833 he travelled to Italy and Greece in order to study the architecture and designs of antiquity. In 1832 he participated for four months in archaeological research at the Acropolis in Athens. During this period he became very interested in the Biedermeier-inspired polychromy debate, which centered on the question whether buildings in Ancient Greece and Rome had been colorfully painted or not. The drawn reconstructions of the painterly decorations of ancient villas he created in Athens inspired his later designs for the painted decorations in Dresden and Vienna. His 1834 publication Vorläufige Bemerkungen über bemalte Architectur und Plastik bei den Alten (Preliminary Remarks on Polychrome Architecture and Sculpture in Antiquity), in which he took a strong position in favor of polychromy - supported by his investigation of pigments on the Trajan's column in Rome - brought him sudden recognition in architectural and aesthetic circles across Europe .

Dresden period (1834–1849)

On September 30, 1834 Semper obtained a post as Professor of Architecture at the Königlichen Akademie der bildenden Künste (today called the Hochschule) in Dresden thanks largely to the efforts and support of his former teacher Franz Christian Gau and swore an oath of allegiance to the King (formerly Elector) of Saxony, Anthony Clement. The flourishing growth of Dresden during this period provided the young architect with considerable creative opportunities. In 1838-40 a synagogue was built in Dresden to Semper's design, it was ever afterward called the Semper Synagogue and is noted for its Moorish Revival interior style.[2] The Synagogue's exterior was built in romanesque style so as not to call attention to itself. The interior design included not only the Moorish inspired wall decorations but furnishings: specifically, a silver lamp of eternal light, which caught Richard Wagner and his wife Cosima's fancy. They gave a great deal of effort to have a copy of this lamp.[3][4] Semper's student, Otto Simonson would construct the magnificent Moorish Revival Leipzig synagogue in 1855.

Certain civic structures remain today, such as the Elbe-facing gallery of the Zwinger Palace complex. His first building for the Dresden Hoftheater burnt down, and the second, today called the Semperoper, was built in 1841. Other buildings also remain indelibly attached to his name, such as the Maternity Hospital, the Synagogue (destroyed during the Third Reich), the Oppenheim Palace, and the Villa Rosa built for the banker Martin Wilhelm Oppenheim. This last construction stands as a prototype of German villa architecture.

On September 1, 1835, Semper married Bertha Thimmig. The marriage ultimately produced six children.

A convinced Republican, Semper took a leading role, along with his friend Richard Wagner, in the May 1849 uprising which swept over the city. He was a member of the Civic Guard (Kommunalgarde) and helped to erect barricades in the streets. When the rebellion collapsed, Semper was considered a leading agitator for democratic change and a ringleader against government authority and he was forced to flee the city.

He was destined never to return to the city that would, ironically, become most associated with his architectural (and political) legacy. The Saxon government maintained a warrant for his arrest until 1863. When the Semper-designed Hoftheater burnt down in 1869, King John, on the urging of the citizenry, commissioned Semper to build a new one. Semper produced the plans but left the actual construction to his son, Manfred.

"What must I have done in 48, that one persecutes me forever? One single barricade did I construct - it held, because it was practical, and as it was practical, it was beautiful", wrote Semper in dismay.[5]

Post-revolutionary period (1849–1855)

After stays in Zwickau, Hof, Karlsruhe and Strasbourg, Semper eventually ended up back in Paris, like many other disillusioned Republicans from the 1848 Revolutions (such as Heinrich Heine and Ludwig Börne). In the fall of 1850, he travelled to London, England. But while he was able to pick up occasional contracts — including participation in the design of the funeral carriage for the Duke of Wellington and the designs of the Canadian, Danish, Swedish, and Ottoman sections of the 1851 Great Exhibition in the Crystal Palace — he found no steady employment. If his stay in London was disappointing professionally, however, it proved a fertile period for Semper's theoretical, creative and academic development. He published Die vier Elemente der Baukunst (The Four Elements of Architecture) in 1851 and Wissenschaft, Industrie und Kunst (Science, Industry and Art) in 1852. These works would ultimately provide the groundwork for his most widely regarded publication, Der Stil in den technischen und tektonischen Künsten oder Praktische Ästhetik, which was published in two volumes in 1861 and 1863.[6]

Zürich period (1855–1871)

Concurrently with the onset of the industrial revolution, the Swiss Federation planned to establish a polytechnical school. As the principal judge for the competition held to select a design for the new building, Semper deemed the submitted entries unsatisfactory and, ultimately, designed the building himself. Proudly situated (where fortified walls once stood), visible from all sides on a terrace overlooking the core of Zurich, the new school became a symbol of a new epoch. The building (1853–1864), which despite frequent remodeling continues to evoke Semper's concept, was initially required to accommodate not only the new school (known today as the ETH Zurich), but the existing University of Zurich, as well.

In 1855 Semper became a professor of architecture at the new school and the success of many of his students who attained success and renown served to ensure his legacy. The Swiss architect Emil Schmid was one such student. With his income as a professor, Semper was able to reunite his family, bringing them to Zurich from Saxony. The City Hall in Winterthur is among other buildings designed by Semper in Switzerland.

Semper provided Bavaria's King Ludwig II with a conceptual design for a theatre dedicated to the work of Richard Wagner to be built in Munich. The project, developed from 1864 to 1866, was never realized, although Wagner 'borrowed' many of its features for his own later theatre at Bayreuth.

Later life (from 1871)

Already in 1833, there were first plans in Vienna for the public presentation of the Imperial Art Collections. With the planning of the Vienna Ring Road, the museum question became pressing again. Works forming the imperial art collection were scattered among several buildings. Semper was assigned to submit a proposal for locating new buildings in conjunction with redevelopment of the Ring Road. In 1869 he designed a gigantic 'Imperial Forum' which was not realized. The National Museum of Art History and the National Museum of Natural History were erected, however, opposite the Palace according to his plan, as was the Burgtheater. In 1871 Semper moved to Vienna to undertake the projects. During construction, repeated disagreements with his appointed associate architect (Karl Freiherr von Hasenauer), led Semper to resign from the project in 1876. In the following year, his health began to deteriorate. He died two years later while on a visit to Italy and is buried in the Protestant Cemetery, Rome. [7]

Legacy

- Semperdepot, Lehargasse, Vienna

Works (selected)

.png)

- Dresden

- Hoftheater – 1838-1841 (destroyed by fire in 1869)

- Villa Rosa – 1839 (destroyed in the Second World War)

- Semper Synagogue – 1839-1840 (destroyed on November 9, 1938 - Kristallnacht)

- Oppenheim-Palace – 1845-1848

- Semper Gallery (Dresden Gemäldegalerie)– 1847-1855

- Neues Hoftheater (Semperoper) – 1871-1878

- Zürich

- City Hall – 1858 (only concept for competition; not built)

- Polytechnical School, (ETH Zurich) – 1858-1864

- Observatory - 1861-1864

- Winterthur

- City Hall – 1865-1869

- Vienna

- Municipal Theater (Burgtheater) – 1873 - 1888

- Museum of Art History (Kunsthistorisches Museum) (1872–1881, finished 1889)

- Natural History Museum (Naturhistorisches Museum) (1872–1881, finished 1891)

See also

Notes

- Dorothea Schröder: "Nibelungenring und mystischer Knoten. Gottfried Sempers Entwurf zu einem Taktstock für Richard Wagner" Jahrbuch des Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg,1993, P.120

- H.A. Meek, The Synagogue, Phaidon, 1995, p. 188

- Colin Eisler "Wagner's Three Synagogues", Artibus et Historiae 2004, Vol. 25/Nr. 50

- Eytan Pessen, Zusammenhängende Reliquien, eine Geschichte über Richard Wagner und Gottfried Semper, pp. 1-22, Semperoper Dresden, Erchien in Wagnerjahr 2013, Spielzeit 2012-2013 & 2013-2014

- Letter to Heinrich Hübsch, January 1852

- Curl, James Stevens (2006). A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (Paperback) (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 880. ISBN 0-19-860678-8.

- Non-Catholic Cemetery in Rome databases Semper Goffredo Archived 2013-02-07 at the Wayback Machine

References

- Berry, J. Duncan. The Legacy of Gottfried Semper. Studies in Späthistorismus (Ph. D. Diss., Brown University, 1989).

- Hvattum, Mari. Gottfried Semper and the Problem of Historicism (Cambridge, 2004). ISBN 0-521-82163-0

- Herrmann, Wolfgang. Gottfried Semper: In Search of Architecture (Cambridge, MA/London, 1984). ISBN 0-262-08144-X

- Karge, Henrik (ed.). Gottfried Semper. Die moderne Renaissance der Künste (Berlin, 2006). ISBN 3-422-06606-3

- Mallgrave, Harry Francis. Gottfried Semper - Architect of the Nineteenth Century (New Haven/London, 1996). ISBN 0-300-06624-4

- Mallgrave, Harry Francis. Modern Architectural Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673-1968 (Cambridge, 2005). ISBN 0-521-79306-8

- Mallgrave, Harry Francis. Architectural Theory: An Anthology from Vitruvius to 1870 (Malden, MA/Oxford, 2006). ISBN 1-4051-0258-6

- Muecke, Mikesch W. Gottfried Semper in Zurich - An Intersection of Theory and Practice (Ames, IA, 2005). ISBN 978-1-4116-3391-9

- Nerdinger, Winfried and Werner Oechslin (eds.). Gottfried Semper 1803-1879 (Munich/Zurich, 2003). ISBN 3-7913-2885-9

- Semper, Gottfried. The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings. Trans. Harry F. Mallgrave and Wolfgang Herrmann (Cambridge, 1989). ISBN 0-521-35475-7

- Semper, Gottfried. Style in the Technical and Tectonic Arts; or, Practical Aesthetics. Trans. Harry F. Mallgrave (Santa Monica, 2004). ISBN 0-89236-597-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gottfried Semper. |

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Villa Garbald

- Semper, Gottfried at Deutsche Biographie (in German)

- Wagner and Semper