Communist Party of Germany

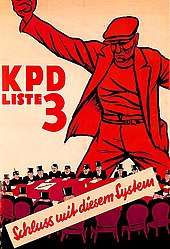

The Communist Party of Germany (German: Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, KPD) was a major political party in the Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1933, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West Germany in the postwar period until it was banned in 1956.

Communist Party of Germany Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founder | |

| Founded | 30 December 1918 – 1 January 1919 |

| Dissolved |

|

| Preceded by | Spartacus League |

| Succeeded by |

|

| Newspaper | Die Rote Fahne |

| Youth wing | Young Communist League |

| Paramilitary wing | Rotfrontkämpferbund (RFB) |

| Membership (1932) | 360,000[7] |

| Ideology |

|

| Political position | Far-left |

| International affiliation | Comintern |

| Colors | Red Yellow |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Communist parties |

|---|

|

Africa

|

|

Europe

Former parties |

|

Oceania

Former parties

|

|

Related topics |

|

Founded in the aftermath of the First World War by socialists who had opposed the war, the party became gradually ever more committed to Leninism and later Stalinism after the death of its founding figures. During the Weimar Republic period, the KPD usually polled between 10 and 15 percent of the vote and was represented in the national Reichstag and in state parliaments. Under the leadership of Ernst Thälmann from 1925 the party became staunchly Stalinist and loyal to the leadership of the Soviet Union, and from 1928 it was largely controlled and funded by the Comintern in Moscow. Under Thälmann's leadership the party directed most of its attacks against the Social Democratic Party of Germany, which it regarded as its main adversary and referred to as "social fascists"; the KPD considered all other parties in the Weimar Republic to be "fascists".[8]

The KPD was banned in the Weimar Republic one day after the Nazi Party emerged triumphant in the German elections in 1933. It maintained an underground organization in Nazi Germany, and the KPD and groups associated with it led the internal resistance to the Nazi regime, with a focus on distributing anti-Nazi literature. The KPD suffered heavy losses between 1933–39, with 30,000 communists executed and 150,000 sent to Nazi concentration camps.[9]

The party was revived in divided postwar West and East Germany and won seats in the first Bundestag (West German Parliament) elections in 1949, but its support collapsed following the establishment of a communist state in the Soviet Occupation Zone in the east. The KPD was banned as extremist in West Germany in 1956 by the Constitutional Court. In 1969, some of its former members founded an even smaller fringe party, the German Communist Party (DKP), which remains legal, and multiple tiny splinter groups claiming to be the successor to the KPD have also subsequently been formed.

In East Germany, the party was merged, by Soviet decree, with remnants of the Social Democratic Party to form the Socialist Unity Party (SED) which ruled East Germany from 1949 until 1989–1990; the forced merger was opposed by the Social Democrats, many of whom fled to the western zones. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, reformists took over the SED and renamed it the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS); in 2007 the PDS subsequently merged with the SPD splinter faction WASG to form Die Linke.

Early history

Before the First World War the Social Democratic Party (SPD) was the largest party in Germany and the world's most successful socialist party. Although still officially claiming to be a Marxist party, by 1914 it had become in practice a reformist party. In 1914 the SPD members of the Reichstag voted in favour of the war. Left-wing members of the party, led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, strongly opposed the war, and the SPD soon suffered a split, with the leftists forming the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD) and the more radical Spartacist League. In November 1918, revolution broke out across Germany. The leftists, led by Rosa Luxemburg and the Spartacist League, formed the KPD at a founding congress held in Berlin on 30 December 1918 – 1 January 1919 in the reception hall of the City Council.[10] Apart from the Spartacists, another dissent group of Socialists called the International Communists of Germany, also dissenting members of the Social Democratic party, but mainly located in Hamburg, Bremen and Northern Germany, joined the young party.[11] The Revolutionary Shop Stewards, a network of dissenting socialist trade unionists centered in Berlin were also invited to the Congress, but eventually did not join the party because they deemed the founding congress leaning into a syndicalist direction.

There were seven main reports given at the founding congress:

- Economical Struggles – by Paul Lange

- Greeting speech – by Karl Radek

- International Conferences – by Hermann Duncker

- Our Organization – by Hugo Eberlein

- Our Program – by Rosa Luxemburg

- The crisis of the USPD – by Karl Liebknecht

- The National Assembly – by Paul Levi

These reports were given by leading figures of the Spartacist League, however members of the Internationale Kommunisten Deutschlands also took part in the discussions

Under the leadership of Liebknecht and Luxemburg, the KPD was committed to a revolution in Germany, and during 1919 and 1920 attempts to seize control of the government continued. Germany's Social Democratic government, which had come to power after the fall of the Monarchy, was vehemently opposed to the KPD's idea of socialism. With the new regime terrified of a Bolshevik Revolution in Germany, Defense Minister Gustav Noske formed a series of anti-communist paramilitary groups, dubbed "Freikorps", out of demobilized World War I veterans. During the failed Spartacist uprising in Berlin of January 1919, Liebknecht and Luxemburg, who had not initiated the uprising but joined once it had begun, were captured by the Freikorps and murdered. The Party split a few months later into two factions, the KPD and the Communist Workers Party of Germany (KAPD).

Following the assassination of Leo Jogiches, Paul Levi became the KPD leader. Other prominent members included Clara Zetkin, Paul Frölich, Hugo Eberlein, Franz Mehring, August Thalheimer, and Ernst Meyer. Levi led the party away from the policy of immediate revolution, in an effort to win over SPD and USPD voters and trade union officials. These efforts were rewarded when a substantial section of the USPD joined the KPD, making it a mass party for the first time.

Through the 1920s the KPD was racked by internal conflict between more and less radical factions, partly reflecting the power struggles between Zinoviev and Stalin in Moscow. Germany was seen as being of central importance to the struggle for socialism, and the failure of the German revolution was a major setback. Eventually Levi was expelled in 1921 by the Comintern for "indiscipline." Further leadership changes took place in the 1920s. Supporters of the Left or Right Opposition to the Stalin-controlled Comintern leadership were expelled; of these, Heinrich Brandler, August Thalheimer and Paul Frölich set up a splinter Communist Party Opposition.

Weimar Republic years

.svg.png)

A new KPD leadership more favorable to the Soviet Union was elected in 1923. This leadership, headed by Ernst Thälmann, abandoned the goal of immediate revolution, and from 1924 onwards contested Reichstag elections, with some success.

In the first five years of Thälmann's leadership, the KPD broadly followed the united front policy developed in the early 1920s of working with other working class and socialist parties to contest elections, pursue social struggles and fight the rising right-wing militias.[12][13][14][15]

During the years of the Weimar Republic, the KPD was the largest Communist party in Europe and was seen as the "leading party" of the Communist movement outside the Soviet Union.[16] It maintained a solid electoral performance, usually polling more than 10% of the vote and gaining 100 deputies in the November 1932 elections. In the presidential election of the same year, Thälmann took 13.2% of the vote, compared to Hitler's 30.1%. Under Thälmann's leadership, the party was closely aligned with the Soviet leadership headed by Joseph Stalin, and from 1928 the party was largely controlled and funded by Comintern in Moscow.[8]

The party's first paramilitary wing was the Roter Frontkämpferbund ("Alliance of Red Front-Fighters"), which was banned by the governing Social Democrats in 1929.[17]

Aligning with the Comintern's ultra-left Third Period the KPD abruptly turned to viewing the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) as its main adversary.[18][8] In this period, the KPD referred to the SPD as "social fascists".[19] The term social fascism was introduced to the German Communist Party shortly after the Hamburg Uprising of 1923 and gradually became ever more influential in the party; by 1929 it was being propagated as a theory.[20] The KPD regarded itself as "the only anti-fascist party" in Germany and held that all other parties in the Weimar Republic were "fascist".[8] Nevertheless, it cooperated with the Nazis in the early 1930s in attacking the social democrats, and both sought to destroy the liberal democracy of the Weimar Republic.[21] In the early 1930s the KPD sought to appeal to Nazi voters with nationalist slogans[8] and in 1931 the KPD had united with the Nazis, whom they then referred to as "working people's comrades", in an unsuccessful attempt to bring down the social democrat state government of Prussia by means of a plebiscite.[22]

During the joint KPD and Nazi campaign to dissolve the Prussian Parliament, Berlin Police Captains Paul Anlauf and Franz Lenck were assassinated in Bülowplatz by Erich Mielke and Erich Ziemer, who were members of the KPD's paramilitary wing, the Parteiselbstschutz. The detailed planning for the murders had been carried out by KPD members of the Reichstag, Heinz Neumann and Hans Kippenberger, based on orders issued by Walter Ulbricht, the Party's leader in the Berlin-Brandenberg region. Shooter Erich Mielke who later became the head of the East German Secret Police, would only face trial for the murders in 1993. In this period, while also opposed to the Nazis, the KPD regarded the Nazi Party as a less sophisticated and thus less dangerous fascist party than the SPD, and KPD leader Ernst Thälmann declared that "some Nazi trees must not be allowed to overshadow a forest" of social democrats.[23]

Critics of the KPD accused it of having pursued a sectarian policy, e.g. the Social Democratic Party criticized the KPD's thesis of "social fascism" (which addressed the SPD as the Communist's main enemy), and both Leon Trotsky, from the Comintern's Left Opposition, and August Thalheimer, of the Right Opposition continued to argue for a united front.[24] Critics believed that the KPD's sectarianism scuttled any possibility of a united front with the SPD against the rising power of the National Socialists. These allegations were repudiated by supporters of the KPD as it was said the right-wing leadership of the SPD rejected the proposals of the KPD to unite for the defeat of fascism. The SPD leaders were accused of having countered KPD efforts to form a united front of the working class. For instance, after Franz von Papen's government carried out a coup d'état in Prussia the KPD called for a general strike and turned to the SPD leadership for joint struggle, but the SPD leaders again refused to cooperate with the KPD.

In 1932, as the party began to shift focus to the fascist threat, the KPD founded Antifaschistische Aktion, commonly known as Antifa, which it described as a "red united front under the leadership of the only anti-fascist party, the KPD".[17]

Nazi era

On 27 February, soon after the appointment of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor, the Reichstag was set on fire and Dutch council communist Marinus van der Lubbe was found near the building. The Nazis publicly blamed the fire on communist agitators in general, although in a German court in 1933, it was decided that van der Lubbe had acted alone, as he claimed to have done. The following day, Hitler persuaded Hindenburg to issue the Reichstag Fire Decree. It suspended the civil liberties enshrined in the constitution, ostensibly to deal with Communist acts of violence.

Repression began within hours of the fire, when police arrested dozens of Communists. Although Hitler could have formally banned the KPD, he did not do so right away. Not only was he reluctant to chance a violent uprising, but he believed the KPD could siphon off SPD votes and split the left. However, most judges held the KPD responsible for the fire, and took the line that KPD membership was in and of itself a treasonous act. At the March 1933 election, the KPD elected 81 deputies. However, it was an open secret that they would never be allowed to take up their seats; they were all arrested in short order. For all intents and purposes, the KPD was "outlawed" on the day the Reichstag Fire Decree was issued, and "completely banned" as of 6 March, the day after the election.[25]

Shortly after the election, the Nazis pushed through the Enabling Act, which allowed the cabinet–in practice, Hitler–to enact laws without the involvement of the Reichstag, effectively giving Hitler dictatorial powers. Since the bill was effectively a constitutional amendment, a quorum of two-thirds of the entire Reichstag had to be present in order to formally call up the bill. Leaving nothing to chance, Reichstag President Hermann Göring did not count the KPD seats for purposes of obtaining the required quorum. This led historian Richard J. Evans to contend that the Enabling Act had been passed in a manner contrary to law. The Nazis did not need to count the KPD deputies for purposes of getting a supermajority of two-thirds of those deputies present and voting. However, Evans argued, not counting the KPD deputies for purposes of a quorum amounted to "refusing to recognize their existence", and was thus "an illegal act".[25]

The KPD was efficiently suppressed by the Nazis. The most senior KPD leaders were Wilhelm Pieck and Walter Ulbricht, who went into exile in the Soviet Union. The KPD maintained an underground organisation in Germany throughout the Nazi period, but the loss of many core members severely weakened the Party's infrastructure.

Purge of 1937

A number of senior KPD leaders in exile were caught up in Joseph Stalin's Great Purge of 1937–38 and executed, among them Hugo Eberlein, Heinz Neumann, Hermann Remmele, Fritz Schulte and Hermann Schubert, or sent to the gulag, like Margarete Buber-Neumann. Still others, like Gustav von Wangenheim and Erich Mielke (later the head of the Stasi in East Germany), denounced their fellow exiles to the NKVD.[26] Willi Münzenberg, the KPD's propaganda chief, was murdered in mysterious circumstances in France in 1940. The NKVD is believed to have been responsible.

Postwar history

In East Germany, the Soviet occupation authorities forced the eastern branch of the SPD to merge with the KPD (led by Pieck and Ulbricht) to form the Socialist Unity Party (SED) in April 1946.[27] Although nominally a union of equals, the SED quickly fell under Communist domination, and most of the more recalcitrant members from the SPD side of the merger were pushed out in short order. By the time of the formal formation of the East German state in 1949, the SED was a full-fledged Communist party, and developed along lines similar to other Soviet-bloc Communist parties.[28] It was the ruling party in East Germany from its formation in 1949 until 1989. The SPD managed to preserve its independence in Berlin, forcing the SED to form a small branch in West Berlin, the Socialist Unity Party of West Berlin.

The KPD reorganised in the western part of Germany, and received 5.7% of the vote in the first Bundestag election in 1949. But the onset of the Cold War and the subsequent widespread repression of the far left soon caused a collapse in the party's support. At the 1953 election the KPD only won 2.2 percent of the total votes and lost all of its seats, never to return. The party was banned in August 1956 by the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany.[27] The decision was upheld by the European Commission of Human Rights in Communist Party of Germany v. the Federal Republic of Germany. The ban was due to the aggressive and combative methods that the party used as a "Marxist-Leninist party struggle" to achieve their goals.

After the party was declared illegal, many of its members continued to function clandestinely despite increased government surveillance. Part of its membership refounded the party in 1968 as the German Communist Party (DKP). Following German reunification many DKP members joined the new Party of Democratic Socialism, formed out of the remains of the SED. In 1968, a self-named "true successor" to the (banned) West German KPD was formed, the KPD/ML (Marxist–Leninist), which followed Maoist ideas. It went through multiple splits and united with a Trotskyist group in 1986 to form the Unified Socialist Party (VSP), which failed to gain any influence and dissolved in the early 1990s.[27] However, multiple tiny splinter groups originating in the KPD/ML still exist, several of which claim the name of KPD. Another party with this name was formed in 1990 in East Berlin by several hardline Communists who had been expelled from the PDS, including Erich Honecker. The "KPD (Bolshevik)" split off from the East German KPD in 2005, bringing the total number of (more or less) active KPDs to at least 5.

The Left, formed out of a merger between the PDS and Labour and Social Justice – The Electoral Alternative in 2007, claims to be the historical successor of the KPD (by way of the PDS).

Organization

In the early 1920s, the party operated under the principle of democratic centralism, whereby the leading body of the party was the Congress, meeting at least once a year.[29] Between Congresses, leadership of the party resided in the Central Committee, which was elected at the Congress, of one group of people who had to live where the leadership was resident and formed the Zentrale and others nominated from the districts they represented (but also elected at the Congress) who represented the wider party.[30] Elected figures were subject to recall by the bodies that elected them.[31]

The KPD employed around about 200 full-timers during its early years of existence, and as Broue notes "They received the pay of an average skilled worker, and had no privileges, apart from being the first to be arrested, prosecuted and sentenced, and when shooting started, to be the first to fall".[32]

Election results

Federal elections

| Election | Votes | Seats | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | +/– | No. | +/– | ||

| 1920 | 589.454 | 2.1 (No. 8) | 4 / 459 |

Boycotted the previous election | ||

| May 1924 | 3.693.280 | 12.6 (No. 4) | 62 / 472 |

After the merger with the left-wing of the USPD | ||

| December 1924 | 2.709.086 | 8.9 (No. 5) | 45 / 493 |

|||

| 1928 | 3.264.793 | 10.6 (No. 4) | 54 / 491 |

|||

| 1930 | 4.590.160 | 13.1 (No. 3) | 77 / 577 |

After the financial crisis | ||

| July 1932 | 5.282.636 | 14.3 (No. 3) | 89 / 608 |

|||

| November 1932 | 5.980.239 | 16.9 (No. 3) | 100 / 584 |

|||

| March 1933 | 4.848.058 | 12.3 (No. 3) | 81 / 647 |

During Hitler's term as Chancellor of Germany | ||

| 1949 | 1.361.706 | 5.7 (No. 5) | 15 / 402 |

First West German federal election | ||

| 1953 | 607.860 | 2.2 (No. 8) | 0 / 402 |

|||

Presidential elections

| Election | Votes | Candidate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | +/– | ||

| 1925 | 1,931,151 | 6.4 (No. 3) | Ernst Thälmann | |

| 1932 | 3,706,759 | 10.2 (No. 3) | Ernst Thälmann | |

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Communist Party of Germany. |

- Communist Party Opposition

- Communist Workers' Party of Germany

- Freies Volk

- German resistance

- German Revolution of 1918–1919

- Hotel Lux, Moscow hotel where many German party members lived in exile

- Luxemburgism

- Revolutionary Trade Union Opposition

- Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Ernst Thälmann, Paul Levi, Erich Mielke, Richard Müller (socialist)

- Rotfrontkämpferbund

- Socialist Workers' Party of Germany

- Sozialistische Volkszeitung

- Spartacus League

- Union of Manual and Intellectual Workers

Footnotes

- Steffen Kailitz: Politischer Extremismus in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Eine Einführung. S. 68.

- Olav Teichert: Die Sozialistische Einheitspartei Westberlins. Untersuchung der Steuerung der SEW durch die SED. kassel university press, 2011, ISBN 978-3-89958-995-5, S. 93. (, p. 93, at Google Books)

- Eckhard Jesse: Deutsche Geschichte. Compact Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-8174-6606-1, S. 264. (, p. 264, at Google Books)

- Bernhard Diestelkamp: Zwischen Kontinuität und Fremdbestimmung. Mohr Siebeck, 1996, ISBN 3-16-146603-9, S. 308. (, p. 308, at Google Books)

- Beschluss vom 31. Mai 1946 der Alliierten Stadtkommandantur: In allen vier Sektoren der ehemaligen Reichshauptstadt werden die Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands und die neugegründete Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands zugelassen.

- Cf. Siegfried Heimann: Ostberliner Sozialdemokraten in den frühen fünfziger Jahren

- Catherine Epstein. The last revolutionaries: German communists and their century. Harvard University Press, 2003. Pp. 39.

- Hoppe, Bert (2011). In Stalins Gefolgschaft: Moskau und die KPD 1928–1933. Oldenbourg Verlag. ISBN 9783486711738.

- https://libcom.org/files/opposition_and_resistance_in_nazi_germany.pdf

- Nettl, J. P. (1969). Rosa Luxemburg (Abridged ed.). London: Oxford U.P. p. 472. ISBN 0-19-281040-5. OCLC 71702.

- Gerhard Engel, The International Communists of Germany, 191z-1919, in: Ralf Hoffrogge / Norman LaPorte (eds.): Weimar Communism as Mass Movement 1918–1933, London: Lawrence & Wishart, pp. 25-45.

- Peterson, Larry (1993). "The United Front". German Communism, Workers' Protest, and Labor Unions. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 399–428. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-1644-2_12. ISBN 978-94-010-4718-0.

- Gaido, Daniel (3 April 2017). "Paul Levi and the Origins of the United-Front Policy in the Communist International". Historical Materialism. Brill. 25 (1): 131–174. doi:10.1163/1569206x-12341515. ISSN 1465-4466.

- Fowkes, Ben (1984). Communism in Germany under the Weimar republic. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-27271-8. OCLC 10553402.

- Bois, Marcel (30 April 2020). "'March Separately, But Strike Together!' The Communist Party's United-Front Policy in the Weimar Republic". Historical Materialism. Brill: 1–28. doi:10.1163/1569206x-00001281. ISSN 1465-4466.

- Ralf Hoffrogge / Norman LaPorte (eds.): Weimar Communism as Mass Movement 1918–1933, London: Lawrence & Wishart, p. 2

- Stephan, Pieroth (1994). Parteien und Presse in Rheinland-Pfalz 1945–1971: ein Beitrag zur Mediengeschichte unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Mainzer SPD-Zeitung 'Die Freiheit'. v. Hase & Koehler Verlag. p. 96. ISBN 9783775813266.

- Grenville, Anthony (1992). "From Social Fascism to Popular Front: KPD Policy as Reflected in the Works of Friedrich Wolf, Anna Seghers and Willi Bredel, 1928–1938". German Writers and Politics 1918–39. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 89–102. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-11815-1_7. ISBN 978-1-349-11817-5.

- Winner, David. "How the left enabled fascism: Ernst Thälmann, leader of Germany's radical left in the last years of the Weimar Republic, thought the centre left was a greater danger than the right". New Statesman.

- Haro, Lea (2011). "Entering a Theoretical Void: The Theory of Social Fascism and Stalinism in the German Communist Party". Critique: Journal of Socialist Theory. 39 (4): 563–582. doi:10.1080/03017605.2011.621248.

- Fippel, Günter (2003). Antifaschisten in "antifaschistischer" Gewalt: mittel- und ostdeutsche Schicksale in den Auseinandersetzungen zwischen Demokratie und Diktatur (1945 bis 1961). A. Peter. p. 21. ISBN 9783935881128.

- Rob Sewell, Germany: From Revolution to Counter-Revolution, Fortress Books (1988), ISBN 1-870958-04-7, Chapter 7.

- Coppi, Hans (1998). "Die nationalsozialistischen Bäume im sozialdemokratischen Wald: Die KPD im antifaschistischen Zweifrontenkrieg (Teil 2)" [The national socialist trees in the social democratic forest: The KPD in the anti-fascist two-front war (Part 2)]. Utopie Kreativ. 97–98: 7–17.

- Marcel Bois, "Hitler wasn't inevitable", Jacobin 11.25.2015

- Evans, Richard J. (2003). The Coming of the Third Reich. New York City: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-0141009759.

- Robert Conquest, The Great Terror, 576-77.

- Eric D. Weitz, Creating German Communism, 1890–1990: From Popular Protests to Socialist State. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997

- David Priestand, Red Flag: A History of Communism," New York: Grove Press, 2009

- Broue, P. (2006) The German Revolution: 1917–1923, Chicago: Haymarket Books, pg.635

- Broue, P. (2006) The German Revolution: 1917–1923, Chicago: Haymarket Books, pg.635-636

- Broue, P. (2006) The German Revolution: 1917–1923, Chicago: Haymarket Books, pg.864 — Broue cites the cases of Freisland and Ernst Meyer as being recalled when their electors were not satisfied with their actions

- Broue, P. (2006) The German Revolution: 1917–1923, Chicago: Haymarket Books, pg.863-864

Further reading

- Rudof Coper, Failure of a Revolution: Germany in 1918–1919. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1955.

- Catherine Epstein, The Last Revolutionaries: German Communists and Their Century. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2003.

- Ruth Fischer, Stalin and German Communism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1948.

- Ben Fowkes, Communism in Germany under the Weimar Republic; London: Palgrave Macmillan 1984.

- John Riddell (ed.), The German Revolution and the Debate on Soviet Power: Documents: 1918–1919: Preparing the Founding Congress. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1986.

- John Green, Willi Münzenberg - Fighter against Fascism and Stalinism, Routledge 2019

- Bill Pelz, The Spartakusbund and the German working class movement, 1914–1919, Lewiston [N.Y.]: E. Mellen Press, 1988.

- Aleksandr Vatlin, "The Testing Ground of World Revolution: Germany in the 1920s," in Tim Rees and Andrew Thorpe (eds.), International Communism and the Communist International, 1919–43. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998.

- Eric D. Weitz, Creating German Communism, 1890–1990: From Popular Protests to Socialist State. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997

- David Priestand, Red Flag: A History of Communism," New York: Grove Press, 2009

- Ralf Hoffrogge, Norman LaPorte (eds.): Weimar Communism as Mass Movement 1918–1933, London: Lawrence & Wishart.