Western Ghats

The Western Ghats, also known as Sahyadri (Benevolent Mountains), are a mountain range that covers an area of 140,000 square kilometres (54,000 sq mi) in a stretch of 1,600 kilometres (990 mi) parallel to the western coast of the Indian peninsula, traversing the states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, Goa, Maharashtra and Gujarat.[1] It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is one of the eight hot-spots of biological diversity in the world.[2][3] It is sometimes called the Great Escarpment of India.[4] It contains a large proportion of the country's flora and fauna, many of which are only found in India and nowhere else in the world.[5] According to UNESCO, the Western Ghats are older than the Himalayas. They influence Indian monsoon weather patterns by intercepting the rain-laden monsoon winds that sweep in from the south-west during late summer.[1] The range runs north to south along the western edge of the Deccan Plateau, and separates the plateau from a narrow coastal plain, called Konkan, along the Arabian Sea. A total of thirty-nine areas in the Western Ghats, including national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and reserve forests, were designated as world heritage sites in 2012 – twenty in Kerala, ten in Karnataka, six in Tamil Nadu and four in Maharashtra.[6][7]

| Western Ghats | |

|---|---|

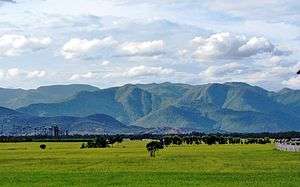

The Western Ghats as seen from Gobichettipalayam, Tamil Nadu | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Anamudi, Kerala, Eravikulam National Park |

| Elevation | 2,695 m (8,842 ft) |

| Coordinates | 10°10′N 77°04′E |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 1,600 km (990 mi) N–S |

| Width | 100 km (62 mi) E–W |

| Area | 160,000 km2 (62,000 sq mi) |

| Geography | |

The Western Ghats lie roughly parallel to the west coast of India.

| |

| Country | India |

| States | |

| Regions | Western India and Southern India |

| Settlements | |

| Biome | Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Cenozoic |

| Type of rock | Basalt, Laterite and Limestone |

| Climbing | |

| Criteria | Natural: ix, x |

| Reference | 1342 |

| Inscription | 2012 (36th session) |

| Area | 795,315 ha |

The range starts near the Songadh town of Gujarat, south of the Tapti river, and runs approximately 1,600 km (990 mi) through the states of Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu ending at Marunthuvazh Malai, at Swamithope near the southern tip of India in Tamil Nadu. These hills cover 160,000 km2 (62,000 sq mi) and form the catchment area for complex riverine drainage systems that drain almost 40% of India. The Western Ghats block southwest monsoon winds from reaching the Deccan Plateau. The average elevation is around 1,200 m (3,900 ft).[8] Kalsubai, the highest peak of Maharashtra is in the Sahyadri Mountains.

The area is one of the world's ten "hottest biodiversity hotspots" and has over 7,402 species of flowering plants, 1,814 species of non-flowering plants, 139 mammal species, 508 bird species, 179 amphibian species, 6,000 insects species and 290 freshwater fish species; it is likely that many undiscovered species live in the Western Ghats. At least 325 globally threatened species occur in the Western Ghats.[9][10][11]

Etymology

The word ghat is explained by numerous Dravidian etymons such as Kannada gaati and ghatta (mountain range), Tulu gatta (hill or hillside), Tamil gattu (hill and hill forest) and ghattam in Malayalam (mountainous way, riverside and hairpin bends).[12]

Ghat, a term used in the Indian subcontinent, depending on the context could either refer to a range of stepped-hill such as the Eastern Ghats and Western Ghats; or the series of steps leading down to a body of water or wharf, such bathing or cremation place along the banks of a river or pond, Ghats in Varanasi, Dhoby Ghaut or Aapravasi Ghat.[13][14] Roads passing through ghats are called Ghat Roads.

Geology

The Western Ghats are the mountainous faulted and eroded edge of the Deccan Plateau. Geologic evidence indicates that they were formed during the break-up of the supercontinent of Gondwana some 150 million years ago. Geophysical evidence indicates that the west coast of India came into being somewhere around 100 to 80 mya after it broke away from Madagascar. After the break-up, the western coast of India would have appeared as an abrupt cliff some 1,000 m (3,300 ft) in elevation.[15] Basalt is the predominant rock found in the hills reaching a thickness of 3 km (2 mi). Other rock types found are charnockites, granite gneiss, khondalites, leptynites, metamorphic gneisses with detached occurrences of crystalline limestone, iron ore, dolerites and anorthosites. Residual laterite and bauxite ores are also found in the southern hills.

Geography

The Western Ghats extend from the Satpura Range in the north, stretching from Gujarat to Tamil Nadu.[16] It traverses south through the states of Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka and Kerala. Major gaps in the range are the Goa Gap, between the Maharashtra and Karnataka sections, and the Palghat Gap on the Tamil Nadu and Kerala border between the Nilgiri Hills and the Anaimalai Hills. The mountains intercept the rain-bearing westerly monsoon winds, and are consequently an area of high rainfall, particularly on their western side. The dense forests also contribute to the precipitation of the area by acting as a substrate for condensation of moist rising orographic winds from the sea, and releasing much of the moisture back into the air via transpiration, allowing it to later condense and fall again as rain.

The northern portion of the narrow coastal plain between the Western Ghats and the Arabian Sea is known as the Konkan, the central portion is called Kanara and the southern portion is called Malabar. The foothill region east of the Ghats in Maharashtra is known as Desh, while the eastern foothills of the central Karnataka state is known as Malenadu.[17] The range is known as Sahyadri in Maharashtra and Karnataka. The Western Ghats meet the Eastern Ghats at the Nilgiri mountains in northwestern Tamil Nadu. The Nilgiris connect the Biligiriranga Hills in southeastern Karnataka with the Shevaroys and Tirumala hills. South of the Palghat Gap are the Anamala Hills, located in western Tamil Nadu and Kerala with smaller ranges further south, including the Cardamom Hills, then Aryankavu pass, and Aralvaimozhi pass near Kanyakumari. The range is known as Sahyan or Sahian in Kerala. In the southern part of the range is Anamudi (2,695 metres (8,842 ft)), the highest peak in the Western Ghats.

Peaks

The Western Ghats have many peaks that rise above 2,000 m (6,600 ft), with Anamudi (2,695 m (8,842 ft)) being the highest peak.

Water bodies

The Western Ghats form one of the four watersheds of India, feeding the perennial rivers of India. The major river systems originating in the Western Ghats are the Godavari, Kaveri, Krishna, Thamiraparani and Tungabhadra rivers. The majority of streams draining the Western Ghats join these rivers, and carry a large volume of water during the monsoon months. These rivers flow to the east due to the gradient of the land and drain out into the Bay of Bengal. Major tributaries include the Bhadra, Bhavani, Bhima, Malaprabha, Ghataprabha, Hemavathi and Kabini rivers. The Periyar, Bharathappuzha, Pamba, Netravati, Sharavathi, Kali, Mandovi and Zuari rivers flow westwards towards the Western Ghats, draining into the Arabian Sea, and are fast-moving, owing to the steeper gradient.

The rivers have been dammed for hydroelectric and irrigation purposes with major reservoirs spread across the states. The reservoirs are important for their commercial and sport fisheries of rainbow trout, mahseer and common carp.[18] There are about 50 major dams along the length of the Western Ghats.[19] Most notable of these projects are the Koyna in Maharashtra, Linganmakki and krishna Raja Sagara in Karnataka, Mettur and Pykara in Tamil Nadu, Parambikulam, Malampuzha and Idukki in Kerala.[17][20][21]

During the monsoon season, numerous streams fed by incessant rain drain off the mountain sides leading to numerous waterfalls. Major waterfalls include Dudhsagar, Unchalli, Sathodi, Magod, Hogenakkal, Jog, Kunchikal, Shivanasamudra, Meenmutty Falls, Athirappilly Falls. Talakaveri is the source of the river Kaveri and the Kuduremukha range is the source of the Tungabhadra. The Western Ghats have several man-made lakes and reservoirs with major lakes at Ooty (34 hectares (84 acres)) in Nilgiris, Kodaikanal (26 hectares (64 acres)) and Berijam in Palani Hills, Pookode lake, Karlad Lake in Wayanad, Vagamon lake, Devikulam (6 hectares (15 acres)) and Letchmi (2 hectares (4.9 acres)) in Idukki, Kerala.

Climate

The area including Agumbe, Hulikal and Amagaon in Karnataka, Mahabaleshwar and Tamhini in Maharashtra are often referred to as the "Cherrapunji of southwest India" or the "rain capital of southwest India". Kollur in Udupi district, Kokkali and Nilkund in Sirsi, Samse in Mudigere of Karnataka, and Neriamangalam in the Ernakulam district of Kerala are the wettest places in the Western Ghats. Heavy precipitation does occur in the surrounding regions due to the long continuity of the mountains without passes and gaps. Changes in the direction and pace of the wind do affect the average rainfall and the wettest places might vary. However, Maharashtra and the northern part of Western Ghats in Karnataka on average receive heavier rainfall than Kerala and the southern part of Western Ghats in Karnataka.

The climate in the Western Ghats varies with altitudinal gradation and distance from the equator. The climate is humid and tropical in the lower reaches tempered by the proximity to the sea. Elevations of 1,500 m (4,921 ft) and above in the north and 2,000 m (6,562 ft) and above in the south have a more temperate climate. The average annual temperature is around 15 °C (59 °F). In some parts frost is common, and temperatures reach the freezing point during the winter months. Mean temperatures range from 20 °C (68 °F) in the south to 24 °C (75 °F) in the north. It has also been observed that the coldest periods in the South Western Ghats coincide with the wettest.[22]

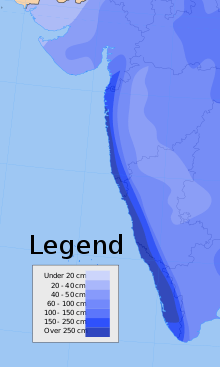

During the monsoon season between June and September, the unbroken Western Ghats chain acts as a barrier to the moisture-laden clouds. The heavy, eastward-moving rain-bearing clouds are forced to rise and in the process deposit most of their rain on the windward side. Rainfall in this region averages 300 centimetres (120 in) to 400 centimetres (160 in) with localised extremes reaching 900 centimetres (350 in). The eastern regions of the Western Ghats, which lie in the rain shadow, receive far less rainfall (about 100 centimetres (39 in)), resulting in an average rainfall of 250 centimetres (98 in) across all regions. The total amount of rain does not depend on the spread of the area; areas in northern Maharashtra receive heavy rainfall followed by long dry spells, while regions closer to the equator receive less annual rainfall and have rain spells lasting several months in a year.[22]

Rainfall

The Karnataka region on average receives heavier rainfall than the Kerala, Maharashtra and Goa. Meanwhile, the Ghats in Karnataka have fewer passes and gaps and therefore the western slopes of Karnataka receive heavy rainfall, over 400 cm more than other regional parts of the Western Ghats.

Some of the wettest places in the Western Ghats are:

Ecoregions

The Western Ghats are home to four tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forest ecoregions – the North Western Ghats moist deciduous forests, North Western Ghats montane rain forests, South Western Ghats moist deciduous forests, and South Western Ghats montane rain forests. The northern portion of the range is generally drier than the southern portion, and at lower elevations makes up the North Western Ghats moist deciduous forests ecoregion, with mostly deciduous forests made up predominantly of teak. Above 1,000 meters elevation are the cooler and wetter North Western Ghats montane rain forests, whose evergreen forests are characterised by trees of the family Lauraceae.

The evergreen forests in Wayanad mark the transition zone between the northern and southern ecoregions of the Western Ghats. The southern ecoregions are generally wetter and more species-rich. At lower elevations are the South Western Ghats moist deciduous forests, with Cullenia the characteristic tree genus, accompanied by teak, dipterocarps, and other trees. The moist forests transition to the drier South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests, which lie in its rain shadow to the east. Above 1,000 meters are the South Western Ghats montane rain forests, also cooler and wetter than the surrounding lowland forests, and dominated by evergreen trees, although some montane grasslands and stunted forests can be found at the highest elevations. The South Western Ghats montane rain forests are the most species-rich ecoregion in peninsular India; eighty percent of the flowering plant species of the entire Western Ghats range are found in this ecoregion.

Biodiversity protection

Historically the Western Ghats were covered in dense forests that provided wild foods and natural habitats for native tribal people. Its inaccessibility made it difficult for people from the plains to cultivate the land and build settlements. After the arrival of the British in the area, large swathes of territory were cleared for agricultural plantations and timber. The forest in the Western Ghats has been severely fragmented due to human activities, especially clear-felling for tea, coffee, and teak plantations[24] from 1860 to 1950. Species that are rare, endemic and habitat specialists are more adversely affected and tend to be lost faster than other species. Complex and species rich habitats like the tropical rainforest are much more adversely affected than other habitats.[25]

The area is ecologically sensitive to development and was declared an ecological hotspot in 1988 through the efforts of ecologist Norman Myers. The area covers five percent of India's land; 27% of all species of higher plants in India (4,000 of 15,000 species) are found here and 1,800 of these are endemic to the region. The range is home to at least 84 amphibian species, 16 bird species, seven mammals, and 1,600 flowering plants which are not found elsewhere in the world. The Government of India has established many protected areas including 2 biosphere reserves, 13 national parks to restrict human access, several wildlife sanctuaries to protect specific endangered species and many reserve forests, which are all managed by the forest departments of their respective state to preserve some of the ecoregions still undeveloped. The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, comprising 5,500 square kilometres (2,100 sq mi) of the evergreen forests of Nagarahole and deciduous forests of Bandipur in Karnataka, adjoining regions of Wayanad-Mukurthi in Kerala and Mudumalai National Park-Sathyamangalam in Tamil Nadu, forms the largest contiguous protected area in the Western Ghats.[26] Silent Valley in Kerala is among the last tracts of virgin tropical evergreen forest in India.[27][28]

In August 2011, the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel (WGEEP) designated the entire Western Ghats as an Ecologically Sensitive Area (ESA) and assigned three levels of Ecological Sensitivity to its different regions.[29] The panel, headed by ecologist Madhav Gadgil, was appointed by the Union Ministry of Environment and Forests to assess the biodiversity and environmental issues of the Western Ghats.[30] The Gadgil Committee and its successor, the Kasturirangan Committee, recommended suggestions to protect the Western Ghats. The Gadgil report was criticised as being too environment-friendly and the Kasturirangan report was labelled as being anti-environmental.[31][32][33]

In 2006, India applied to the UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB) for the Western Ghats to be listed as a protected World Heritage Site.[34] In 2012, the following places were declared as World Heritage Sites:[35][36]

- Kali Tiger Reserve, Dandeli, Karnataka

- Indira Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary and National Park, Tamil Nadu

- Mundigekere Bird Sanctuary, Sirsi, Karnataka

- Kalakkad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve, Tamil Nadu

- Thattekad Bird Sanctuary, Kerala

- Shendurney Wildlife Sanctuary, Kerala

- Neyyar Wildlife Sanctuary, Kerala

- Peppara Wildlife Sanctuary, Kerala

- Periyar Tiger Reserve, Kerala

- Srivilliputtur Wildlife Sanctuary, Tamil Nadu

- Eravikulam National Park, Kerala

- Grass Hills National Park, Tamil Nadu and Kerala

- Karian Shola National Park, Karnataka

- Sathyamangalam Wildlife Sanctuary, Tamil Nadu

- Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary, Kerala

- Silent Valley National Park, Kerala

- Mukurthi National Park, Tamil Nadu

- Pushpagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, Karnataka

- Brahmagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, Karnataka

- Mookambika Wildlife Sanctuary

- Talakaveri Wildlife Sanctuary, Karnataka

- Aralam Wildlife Sanctuary, Kerala

- Kudremukh National Park, Karnataka

- Someshwara Wildlife Sanctuary, Karnataka

- Kaas Plateau, Maharashtra

- Bhimashankar Wildlife Sanctuary, Maharashtra

- Koyna Wildlife Sanctuary, Maharashtra

- Chandoli National Park, Maharashtra

- Radhanagari Wildlife Sanctuary, Maharashtra

- Parambikulam Wildlife Sanctuary, Kerala

- Pambadum Shola National Park, Kerala

- Anamudi Shola National Park, Kerala

- Chimmony Wildlife Sanctuary

- Peechi-Vazhani Wildlife Sanctuary, Kerala

- Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary, Kerala

- Mathikettan Shola National Park, Kerala

- Kurinjimala Sanctuary, Kerala

- Karimpuzha National Park, Kerala

- Idukki Wildlife Sanctuary

- Ranipuram National Park

- Megamalai Wildlife Sanctuary, Tamil Nadu

- Palani Hills Wildlife Sanctuary and National Park, Tamil Nadu

- Kanyakumari Wildlife Sanctuary, Tamil Nadu

- Bandipur National Park , Karnataka

- Nagarhole National Park, Karnataka

- Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, Tamil Nadu

Fauna

The Western Ghats are home to thousands of animal species including at least 325 globally threatened species.[37]

Mammals

There are at least 139 mammal species. Of the 16 endemic mammals, 13 are threatened. Among the 32 threatened species are the critically endangered Malabar large-spotted civet, the endangered lion-tailed macaque, Nilgiri tahr, Bengal tiger and Indian elephants, the vulnerable Indian leopard, Nilgiri langur and gaur.[38][39][40]

These hill ranges serve as important wildlife corridors and form an important part of Project Elephant and Project Tiger reserves. The largest population of tigers outside the Sundarbans is in the Western Ghats, where there are seven populations with an estimated population size of 336 to 487 individuals occupying 21,435 km2 (8,276 sq mi) of forest in three major landscape units spread across Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala.[41] The Western Ghats ecoregion has the largest Indian elephant population in the wild with an estimated 11,000 individuals across eight distinct populations.[42][43] The endemic Nilgiri tahr, which was on the brink of extinction, has recovered and has an estimated 3,122 individuals in the wild.[44] The critically endangered endemic Malabar large-spotted civet is estimated to number fewer than 250 mature individuals, with no sub-population greater than 50 individuals.[45] About 3500 lion-tailed macaques live scattered over several areas in the Western Ghats.[46]

The Western Ghats have the largest tiger population outside Sunderbans.

The Western Ghats have the largest tiger population outside Sunderbans. The endangered lion-tailed macaque is endemic to the Western Ghats.

The endangered lion-tailed macaque is endemic to the Western Ghats..jpg) The Western Ghats region has the largest Indian elephant population in India.

The Western Ghats region has the largest Indian elephant population in India.- Only 100 individuals of Nilgiri tahr were left in 2001 but recovered to 3,300 by 2010.

_by_N._A._Naseer.jpg) The endemic Nilgiri langur is endangered.

The endemic Nilgiri langur is endangered.

Reptiles

The major population of the snake family Uropeltidae is restricted to the region.[47] Several endemic reptile genera occur here, including the cane turtle Vijayachelys silvatica, lizards like Salea, Ristella, Kaestlea, snakes like Melanophidium, Plectrurus, Teretrurus, Platyplectrurus, Xylophis, Rhabdops and so on. Species-level endemism is much higher and is common to almost all genera present here. Some enigmatic endemic reptiles include the venomous snakes such as the striped coral snake, the Malabar pit viper, the large-scaled pitviper and the horseshoe pitviper. The region has a significant population of the vulnerable mugger crocodile.[48]

Amphibians

The amphibians of the Western Ghats are diverse and unique, with more than 80% of the 179 amphibian species being endemic to the rainforests of the mountains.[49] The endangered purple frog was discovered in 2003.[50] Several families of frogs, namely of the genera Micrixalus, Indirana, Nyctibatrachus, are endemic to this region. Endemic genera include the toads Pedostibes, Ghatophryne, Xanthophryne; arboreal frogs such as Ghatixalus, Mercurana and Beddomixalus; and microhylids like Melanobatrachus. New frog species were described from the Western Ghats in 2005, and more recently a new species, monotypic of its genus Mysticellus, was discovered.[51][52] The region is also home to many caecilian species.

- The region has a significant population of the vulnerable mugger crocodile.

The purple frog (Nasikabatrachus sahyadrensis) was discovered in 2003.

The purple frog (Nasikabatrachus sahyadrensis) was discovered in 2003. The Malabar gliding frog is endemic to the Western Ghats.

The Malabar gliding frog is endemic to the Western Ghats. Pipe snakes are found only in South India and Sri Lanka.

Pipe snakes are found only in South India and Sri Lanka. Denison's barb is threatened from habitat loss and is now bred in captivity.

Denison's barb is threatened from habitat loss and is now bred in captivity.

Fish

As of 2004, 288 freshwater fish species were listed for the Western Ghats, including 35 also known from brackish or marine water.[11] Several new species have been described from the region since then (e.g., Dario urops and S. sharavathiensis).[53][54] There are 118 endemic species, including 13 genera entirely restricted to the Western Ghats (Betadevario, Dayella, Haludaria, Horabagrus, Horalabiosa, Hypselobarbus, Indoreonectes, Lepidopygopsis, Longischistura, Mesonoemacheilus, Parapsilorhynchus, Rohtee and Travancoria).[55]

There is a higher fish richness in the southern part of the Western Ghats than in the northern,[55] and the highest is in the Chalakudy River, which alone holds 98 species.[56] Other rivers with high species numbers include the Periyar, Bharatapuzha, Pamba and Chaliyar, as well as upstream tributaries of the Kaveri, Pambar, Bhavani and Krishna rivers.[55] The most species rich families are the Cyprinids (72 species), hillstream loaches (34 species; including stone loaches, now regarded a separate family), Bagrid catfishes (19 species) and Sisorid catfishes (12 species).[11][55][56] The region is home to several brilliantly coloured ornamental fishes like the Denison (or red line torpedo) barb,[57] melon barb, several species of Dawkinsia barbs, zebra loach, Horabagrus catfish, dwarf pufferfish and dwarf Malabar pufferfish.[58] The rivers are also home to Osteobrama bakeri, and larger species such as the Malabar snakehead and Malabar mahseer.[59][60] A few are adapted to an underground life, including some Monopterus swampeels,[61] and the catfish Horaglanis and Kryptoglanis.[62]

According to the IUCN, 97 freshwater fish species from the Western Ghats were considered threatened in 2011, including 12 critically endangered, 54 endangered and 31 vulnerable.[55] All but one (Tor khudree) of these are endemic to the Western Ghats. An additional 26 species from the region are considered data deficient (their status is unclear at present). The primary threats are from habitat loss, but also from overexploitation and introduced species.[55]

Birds

There are at least 508 bird species. Most of Karnataka's five hundred species of birds are from the Western Ghats region.[63][64] There are at least 16 species of birds endemic to the Western Ghats including the endangered rufous-breasted laughingthrush, the vulnerable Nilgiri wood-pigeon, white-bellied shortwing and broad-tailed grassbird, the near threatened grey-breasted laughingthrush, black-and-rufous flycatcher, Nilgiri flycatcher, and Nilgiri pipit, and the least concern Malabar (blue-winged) parakeet, Malabar grey hornbill, white-bellied treepie, grey-headed bulbul, rufous babbler, Wayanad laughingthrush, white-bellied blue-flycatcher and the crimson-backed sunbird.[65]

Nilgiri wood-pigeon

Nilgiri wood-pigeon

_-_Male_-_Sakleshpur_-_India_-2009.jpg)

Insects

There are roughly 6,000 insect species.[66] Of 334 Western Ghats butterfly species, 316 species have been reported from the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve.[67] The Western Ghats are home to 174 species of odonates (107 dragonflies and 67 damselflies), including 69 endemics.[55] Most of the endemic odonate are closely associated with rivers and streams, while the non-endemics typically are generalists.[55] There are several species of leeches found all along the Western Ghats.[68]

The Malabar tree nymph is endemic to the Western Ghats.

The Malabar tree nymph is endemic to the Western Ghats. Tamil Lacewings are found only in South Asia.

Tamil Lacewings are found only in South Asia. The Western Ghats have 67 species of damselflies.

The Western Ghats have 67 species of damselflies. The endemic land snail Indrella ampulla

The endemic land snail Indrella ampulla Phallus indusiatus found in the Western Ghats

Phallus indusiatus found in the Western Ghats

Molluscs

Seasonal rainfall patterns of the Western Ghats necessitate a period of dormancy for its land snails, resulting in their high abundance and diversity including at least 258 species of gastropods from 57 genera and 24 families.[69] A total of 77 species of freshwater molluscs (52 gastropods and 25 bivalves) have been recorded from the Western Ghats, but the actual number is likely higher.[55] This include 28 endemics. Among the threatened freshwater molluscs are the mussels Pseudomulleria dalyi, which is a Gondwanan relict, and the snail Cremnoconchus, which is restricted to the spray zone of waterfalls.[55] According to the IUCN, 4 species of freshwater molluscs are considered endangered and 3 are vulnerable. An additional 19 species are considered data deficient.[55]

Flora

Of the 7,402 species of flowering plants occurring in the Western Ghats, 5,588 species are native or indigenous and 376 are exotics naturalised; 1,438 species are cultivated or planted as ornamentals. Among the indigenous species, 2,253 species are endemic to India and of them, 1,273 species are exclusively confined to the Western Ghats. Apart from 593 confirmed subspecies and varieties; 66 species, 5 subspecies and 14 varieties of doubtful occurrence are also reported, amounting to 8,080 taxa of flowering plants.[70]

See also

Notes

- "Western Ghats".

- Myers, Norman; Mittermeier, Russell A.; Mittermeier, Cristina G.; Da Fonseca, Gustavo A. B.; Kent, Jennifer (2000). "Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities". Nature. 403 (6772): 853–858. doi:10.1038/35002501. PMID 10706275.

- "UN designates Western Ghats as world heritage site". Times of India. 2 July 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- Migon, Piotr (12 May 2010). Geomorphological Landscapes of the World. Springer. p. 257. ISBN 978-90-481-3054-2.

- A biodiversity hotspot

- "Western Ghats". UNESCO. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Lewis, Clara (3 July 2012). "39 sites in Western Ghats get world heritage status". Times of India. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- "The Peninsula". Asia-Pacific Mountain Network. Archived from the original on 12 August 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2007.

- Nayar, T.S.; Rasiya Beegam, A; Sibi, M. (2014). Flowering Plants of the Western Ghats, India (2 Volumes). Thiruvananthapuram, India: Jawaharlal Nehru Tropical Botanic Garden and Research Institute. p.1700.

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Fonseca, G.A.B.Da; Kent, J. (2000). "Biodiversity Hotspots for Conservation Priorities". Nature. 403 (6772): 853–858. doi:10.1038/35002501. PMID 10706275.

- Dahanukar, N.; Raut, R.; Bhat, A. (2004). "Distribution, endemism and threat status of freshwater fishes in the Western Ghats of India". Journal of Biogeography. 31 (1): 123–136. doi:10.1046/j.0305-0270.2003.01016.x.

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (2003). Jainism and Early Buddhism. Jain Publishing Company. pp. 523–538. ISBN 9780895819567.

- Sunithi L. Narayan, Revathy Nagaswami, 1992, Discover sublime India: handbook for tourists, Page 5.

- Ghat definition, Cambridge dictionary.

- Barron, E.J.; Harrison, C.G.A.; Sloan, J.L. II; Hay, W.W. (1981). "Paleogeography, 180 million years ago to the present". Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae. 74 (2): 443–470.

- "Western Ghats - UNESCO World Heritage Centre".

- "The Geography of India". all-about-india.com. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- Sehgal, K. L. "Coldwater fish and fisheries in the Western Ghats, India". FAO. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- "Indian Dams by River and State". Rain water harvesting. Retrieved 19 March 2007.

- Menon, Rajesh (3 October 2005). "Tremors may rock Koyna for another two-decade". Indian Express. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2007.

- Samani, R.L.; Ayhad, A.P. (2002). "Siltation of Reservoirs-Koyna Hydroelectric Project-A Case Study". In S. P. Kaushish; B. S. K. Naidu (eds.). Silting Problems in Hydropower Plants. Bangkok: Central Board of Irrigation and Power. ISBN 978-90-5809-238-0.

- Ranjit Daniels, R.J. "Biodiversity of the Western Ghats – An Overview". Wildlife Institute of India. Archived from the original on 28 February 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2007.

- https://en.climate-data.org

- "Camp at world's highest tea estate Kolukkumalai". OnManorama. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- Kumar, Ajith. "Impact of rainforest fragmentation on small mammals and herpetofauna in the Western Ghats, South India" (PDF). Salim Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, Coimbatore. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "The Nilgiri Bio-sphere Reserve". Archived from the original on 28 September 2006.

- Ramesh (21 November 2009). "No clearance for mining, hydel projects that destroy Western Ghat". The Hindu. Palakkad: Kasturi & Sons Ltd. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- staff (4 August 2009). "Gundia project has not got Centre's nod". The Hindu. Chennai, India: Kasturi & Sons Ltd. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- Madhav Gadgil (31 August 2012). "Report of the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel" (PDF). Westernghatindia.org. Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India. Part 1: summary XIX. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- "Vested interests in Western Ghats". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- "Report is anti environmental". The Hindu. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Disaster for Western Ghats".

- "Paradise lost". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "World Heritage sites, Tentative lists, Western Ghats sub cluster". UNESCO. 2007. Retrieved 30 March 2007.

- "UNESCO heritage sites". UNESCO. Retrieved 30 March 2007.

- "UN designates Western Ghats as world heritage site". Times of India. 2 July 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Nameer, P.O.; Molur, Sanjay; Walker, Sally (November 2001). "Mammals of the Western Ghats: A Simplistic Overview". Zoos' Print Journal. 16 (11): 629–639. doi:10.11609/jott.zpj.16.11.629-39.

- Participants of CBSG CAMP workshop: Status of South Asian Primates (March 2002) (2004). "Macaca silenus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2004. Retrieved 9 May 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Database entry includes justification for why this species is endangered

- Mewa, Singh; Werner, Kaumanns (2005). "Behavioural studies: A necessity for wildlife management" (PDF). Current Science. 89 (7): 1233. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2007.

- Malviya, M.; Srivastav, A.; Nigam, P.; Tyagi, P.C. (2011). "Indian National Studbook of Nilgiri Langur (Trachypithecus johnii)" (PDF). Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun and Central Zoo Authority, New Delhi.

- Jhala, Y. V.; Gopal, R.; Qureshi, Q (2008). "Status of the Tigers, co-predators, and Prey in India" (PDF). TR 08/001. National Tiger Conservation Authority, Govt. of India, New Delhi; Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Elephant Reserves". ENVIS Centre on Wildlife & Protected Areas. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- "Census population 2005" (PDF). Note on Project Elephant. Ministry of Environment and Forests. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- "Nilgiri tahr population over 3,000: WWF-India". The Hindu. 3 October 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Jennings, A.; Veron, G. & Helgen, K. (2008). "Viverra civettina". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Molur S; D Brandon-Jones; W Dittus; A. Eudey; A. Kumar; M. Singh; M.M. Feeroz; M. Chalise; P. Priya & S. Walker (2003). "Status of South Asian Primates: Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (C.A.M.P.) Workshop Report, 2003". Zoo Outreach Organization/CBSG-South Asia, Coimbatore. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Greene, H. W. & R. W. Mcdiarmid (2005). Wallace and Savage: heroes, theories and venomous snake mimicry, Ecology and Evolution in the Tropics, a Herpetological Perspective. Chicago University of Chicago Press. pp. 190–208.

- Harry V., Andrews, Status and Distribution of the Mugger Crocodile in Tamil Nadu, WII, archived from the original on 20 December 2004

- Vasudevan Karthikeyan, A Report on the Survey of Rainforest Fragments in the Western Ghats for Amphibian Diversity, archived from the original on 15 December 2005

- Radhakrishnan, C; K.C. Gopi & K.P. Dinesh (2007). "Zoogeography of Nasikabatrachus sahyadrensis Biju and Bossuyt (Amphibia: Anura; Nasikabatrachidae) in the Western Ghats, India". Records of the Zoological Survey of India. 107: 115–121.

- "An evaluation of the endemism of the amphibian assemblages from the Western Ghats using molecular techniques" (PDF). WII. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "New 'mysterious' frog species discovered in India's Western Ghats". BBC News. 13 February 2019.

- Britz; Ali; Philip (2012). "Dariourops, a new species of badid fish from the Western Ghats, southern India". Zootaxa. 3348: 63–68. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3348.1.5.

- Sreekantha; Gururaja; Remadevi; Indra; Ramachandra (2006). "Two new species of the genus Schistura McClell and (Cypriniformes: Balitoridae) from western Ghats, India". Zoos' Print Journal. 21 (4): 2211–2216. doi:10.11609/jott.zpj.1386.2211-6.

- Molur, M.; Smith, K.G.; Daniel, B.A. & Darwall, W.R.T. (2011). The status and distribution of freshwater biodiversity in the Western Ghats, India (PDF). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species – Regional Assessment. ISBN 978-2-8317-1381-6.

- Raghavan; Prasad; Ali; Pereira (2008). "Fish fauna of Chalakudy River, part of Western Ghats biodiversity hotspot, Kerala, India: patterns of distribution, threats and conservation needs". Biodiversity and Conservation. 17 (13): 3119–3131. doi:10.1007/s10531-007-9293-0.

- Raghavan, R., Philip, S., Ali, A. & Dahanukar, N. (2013): Sahyadria, a new genus of barbs (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) from Western Ghats of India. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 5 (15): 4932-4938.

- "Zoologica" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2004. Retrieved 18 December 2006.

- Benziger; Philip; Raghavan; Ali; Sukumaran; Tharian; Dahanukar; Baby; Peter; Devi; Radhakrishnan; Haniffa; Britz; Antunes (2011). "Unraveling a 146 Years Old Taxonomic Puzzle: Validation of Malabar Snakehead, Species-Status and Its Relevance for Channid Systematics and Evolution". PLOS One. 6 (6): e21272. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021272. PMC 3123301. PMID 21731689.

- Silas; et al. (2005). "Indian Journal of Fisheries". 52 (2): 125–140. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gobi, K.C. (2002). "A new synbranchid fish, Monopterus digressus from Kersla, Peninsular India". Rec. Zool. Surv. India. 100 (1–2): 137–143.

- Vincent, Moncey; Thomas, John (April 2011). "Kryptoglanis shajii, an enigmatic subterranean-spring catfish (Siluriformes, Incertae sedis) from Kerala, India". Ichthyological Research. 58 (2): 161–165. doi:10.1007/s10228-011-0206-6.

- "Karnataka birds". karnatakabirds.net. Archived from the original on 29 April 2006.

- "Karnataka forest department (forests at a glance – Bio-diversity". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- "Restricted-range species". BirdLife EBA Factsheet 12 : Western Ghats. BirdLife International. 1998. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

- Mathew George & Binoy C.F., An Overview of Insect Diversity of Western Ghats with Special Reference to Kerala State, WII, archived from the original on 16 March 2009, retrieved 24 July 2007

- George Mathew & M. Mahesh Kumar, State of the Art Knowledge on the Butterflies of Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, WII, archived from the original on 8 January 2009

- Chandra, Mahesh (1976). "Collection of leeches from Maharashtra" (PDF). Zoological Survey of India. 69 : 325–328. Rec. Zool. Surv. India. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- Madhyastha N. A.; Rajendra; Mavinkurve G. & Shanbhag Sandhya P., Land Snails of Western Ghats, WII, archived from the original on 17 July 2009

- Nayar, T.S., Rasiya Beegam A., and M. Sibi. (2014). Flowering Plants of the Western Ghats, India (2 Volumes), Jawaharlal Nehru Tropical Botanic Garden and Research Institute, Palode, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India. p.1700

References

- Mahajan, Harshal. A rendezvous with Sahyadri

- Ingalhalikar, Shrikant. Flowers of Sahyadri. Corolla Publication; Pune

- Wikramanayake, Eric; Eric Dinerstein; Colby J. Loucks; et al. (2002). Terrestrial Ecoregions of the Indo-Pacific: a Conservation Assessment. Island Press; Washington, DC.

- Kapadia, Harish. Trek the Sahyadris

- Daniels, R.J. Ranjit, Wildlife institute of India, "Biodiversity in the Western Ghats"

- Ajith Kumar, Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, Coimbatore, India, Ravi Chellam, B.C.Choudhury, Divya Mudappa, Karthikeyan Vasudevan, N.M.Ishwar, Wildlife Institute of India, Dehra Dun, India, Barry Noon, Department of Fish and Wildlife Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, U.S. (2002) "Impact of Rainforest Fragmentation on Small Mammals and Herpetofauna in the Western Ghats, South India", Final Report, pp. 146, illus. Full text retrieved 14 March 2007

- Verma Desh Deepak (2002) "Thematic Report on Mountain Ecosystems", Ministry of Environment and Forests,13pp, retrieved 27 March 2007 Thematic Report on Mountain Ecosystems Full text, detailed data, not cited.

- Abstracts, Edited by Lalitha Vijayan, Saconr. Vasudeva, University of Dharwad, Priyadarsanan, ATREE, Renee Borges, CES, ISSC, Jagdish Krishnaswamy, Atree & WCSP. Pramod, Sacon, Jagannatha Rao, R., FRLHTR. J. Ranjit Daniels, Care Earth, Compiled by S. Somasundaram, Sacon (1–2 December 2005) Integrating Science and Management of Biodiversity in the Western Ghats, 2nd National Conference of the Western Ghats Forum, Venue: State Forest Service College Coimbatore, Organized by Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, Anaikatty, Coimbatore – 641108, India. Sponsored by Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India. Supported by The Arghyam Foundation, The Ford Foundation & Sir Dorabiji Trust Through Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE)

- Shifting Cultivation, Sacred Groves and Conflicts in Colonial Forest Policy in the Western Ghats. M.D. Subash Chandran; Chapter 22

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Western Ghats. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Western Ghats. |

- Western Ghats, UNESCO World Heritage site

- Western Ghats, WWF