Saarbrücken

Saarbrücken (/sɑːrˈbrʊkən/,[4] also US: /zɑːrˈ-, ˈsɑːrbrʊkən, ˈzɑːr-/,[5][6] German: [zaːɐ̯ˈbʁʏkn̩] (![]()

Saarbrücken | |

|---|---|

Saarbrücken in January 2006 | |

Coat of arms | |

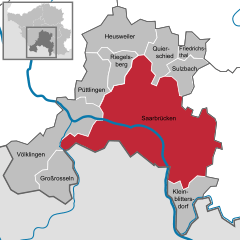

Location of Saarbrücken within Saarbrücken district   | |

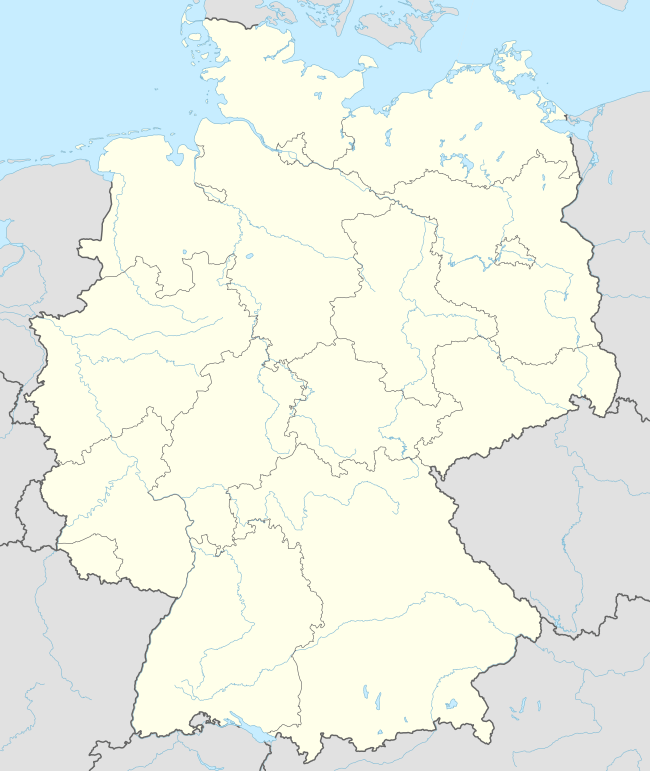

Saarbrücken  Saarbrücken | |

| Coordinates: 49°14′N 7°0′E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Saarland |

| District | Saarbrücken |

| Subdivisions | 20 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Uwe Conradt (CDU) |

| Area | |

| • City | 167.07 km2 (64.51 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 230.1 m (754.9 ft) |

| Population (2018-12-31)[1] | |

| • City | 180,741 |

| • Density | 1,100/km2 (2,800/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 329,593[2] |

| • Metro | 700,000[3] |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) |

| Postal codes | 66001–66133 |

| Dialling codes | 0681, 06893, 06897, 06898, 06805 |

| Vehicle registration | SB |

| Website | www.saarbruecken.de |

Saarbrücken was created in 1909 by the merger of three towns, Saarbrücken, St. Johann, and Malstatt-Burbach. It was the industrial and transport centre of the Saar coal basin. Products included iron and steel, sugar, beer, pottery, optical instruments, machinery, and construction materials.

Historic landmarks in the city include the stone bridge across the Saar (1546), the Gothic church of St. Arnual, the 18th-century Saarbrücken Castle, and the old part of the town, the Sankt Johanner Markt (Market of St. Johann).

In the 20th century, Saarbrücken was twice separated from Germany: in 1920–35 as capital of the Territory of the Saar Basin and in 1947–56 as capital of the Saar Protectorate.

Toponymy

In modern German, Saarbrücken literally translates to Saar bridges (Brücken is the plural of Brücke), and indeed there are about a dozen bridges across the Saar river. However, the name actually predates the oldest bridge in the historic center of Saarbrücken, the Alte Brücke, by at least 500 years.[wp 1]

The name Saar stems from the Celtic word sara (streaming water), and the Roman name of the river, saravus.[8]

However, there are three theories about the origin of the second part of the name Saarbrücken.

Briga (rock)

The most popular theory states that the historical name of the town, Sarabrucca, derived from the Celtic word briga (hill, or rock, big stone[8]), which became Brocken (can mean rock or boulder) in High German. The castle of Sarabrucca was located on a large rock by the name of Saarbrocken overlooking the river Saar.[9]

Brucca (ford)

A minority opinion holds that the historical name of the town, Sarabrucca, derived from the Old High German word Brucca(in German), meaning bridge, or more precisely a Corduroy road, which was also used in fords. Next to the castle, there was a ford allowing land-traffic to cross the Saar.[10]

Bruco (swamp)

A mostly rejected theory claims that the historical name of the town, Sarabrucca, derived from the Germanic word bruco (swamp, marsh). There is an area in St Johann called Bruchwiese (wiese meaning meadow), which used to be swampy before it was developed, and there were flood-meadows along the river, and those are often marshy. However, the Saarbrücken area was first settled by Celts and not by Germanic peoples.[wp 1]

History

Roman Empire

In the last centuries BC, the Mediomatrici settled in the Saarbrücken area.[11] When Julius Caesar conquered Gaul in the 1st century BC, the area was incorporated into the Roman Empire.

From the 1st century AD to the 5th century,[12] there was the Gallo-Roman settlement called vicus Saravus west of Saarbrücken's Halberg hill,[13] on the roads from Metz to Worms and from Trier to Strasbourg.[10] Since the 1st or 2nd century AD,[10] a wooden bridge, later upgraded to stone,[9] connected vicus Saravus with the south-western bank of the Saar, today's St Arnual, where at least one Roman villa was located.[14] In the 3rd century AD, a Mithras shrine was built in a cave in Halberg hill, on the eastern bank of the Saar river, next to today's old "Osthafen" harbor,[15] and a small Roman camp was constructed at the foot of Halberg hill[13] next to the river.[12]

Toward the end of the 4th century, the Alemanni destroyed the castra and vicus Saravus, removing permanent human presence from the Saarbrücken area for almost a century.[10]

Middle Ages to 18th century

The Saar area came under the control of the Franks towards the end of the 5th century. In the 6th century, the Merovingians gave the village Merkingen, which had formed on the ruins of the villa on the south-western end of the (in those times still usable) Roman bridge, to the Bishopric of Metz. Between 601 and 609, Bishop Arnual founded a community of clerics, a Stift, there. Centuries later the Stift, and in 1046 Merkingen, took on his name, giving birth to St Arnual.[10]

The oldest documentary reference to Saarbrücken is a deed of donation from 999, which documents that Emperor Otto III gave the "castellum Sarabrucca" (Saarbrücken castle) to the Bishops of Metz. The Bishops gave the area to the Counts of Saargau as a fief.[10] By 1120, the county of Saarbrücken had been formed and a small settlement around the castle developed. In 1168, Emperor Barbarossa ordered the slighting of Saarbrücken because of a feud with Count Simon I. The damage cannot have been grave, as the castle continued to exist.[16]

In 1321/1322[9] Count Johann I of Saarbrücken-Commercy gave city status to the settlement of Saarbrücken and the fishing village of St Johann on the opposite bank of the Saar, introducing a joint administration and emancipating the inhabitants from serfdom.[11]

From 1381 to 1793 the counts of Nassau-Saarbrücken were the main local rulers. In 1549, Emperor Charles V prompted the construction of the Alte Brücke (old bridge) connecting Saarbrücken and St Johann. At the beginning of the 17th century, Count Ludwig II ordered the construction of a new Renaissance-style castle on the site of the old castle, and founded Saarbrücken's oldest secondary school, the Ludwigsgymnasium. During the Thirty Years' War, the population of Saarbrücken was reduced to just 70 by 1637, down from 4500 in 1628. During the Franco-Dutch War, King Louis XIV's troops burned down Saarbrücken in 1677, almost completely destroying the city such that just 8 houses remained standing.[11] The area was incorporated into France for the first time in the 1680s. In 1697 France was forced to relinquish the Saar province, but from 1793 to 1815 regained control of the region.

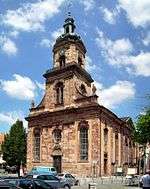

During the reign of Prince William Henry from 1741 to 1768, the coal mines were nationalized and his policies created a proto-industrialized economy, laying the foundation for Saarland's later highly industrialized economy. Saarbrücken was booming, and Prince William Henry spent on building and on infrastructure like the Saarkran river crane (1761), far beyond his financial means. However, the famous baroque architect Friedrich Joachim Stengel created not only the Saarkran, but many iconic buildings that still shape Saarbrücken's face today, like the Friedenskirche (Peace Church), which was finished in 1745, the Old City Hall (1750), the catholic St. John's Basilica (1754), and the famous Ludwigskirche (1775), Saarbrücken's landmark.[11]

19th century

_b_753.jpg)

In 1793, Saarbrücken was captured by French Revolutionary troops and in the treaties of Campo Formio and Lunéville, the county of Saarbrücken was ceded to France.[11]

After 1815 Saarbrücken became part of the Prussian Rhine Province. The office of the mayor of Saarbrücken administered the urban municipalities Saarbrücken and St Johann, and the rural municipalities Malstatt, Burbach, Brebach, and Rußhütte. The coal and iron resources of the region were developed: in 1852, a railway connecting the Palatine Ludwig Railway with the French Eastern Railway was constructed, the Burbach ironworks started production in 1856, beginning in 1860 the Saar up to Ensdorf was channeled, and Saarbrücken was connected to the French canal network.[11]

At the start of the Franco-Prussian War, Saarbrücken was the first target of the French invasion force which drove off the Prussian vanguard and occupied Alt-Saarbrücken on 2 August 1870. Oral tradition has it that 14-year-old French Prince Napoléon Eugène Louis Bonaparte fired his first cannon in this battle, an event commemorated by the Lulustein memorial in Alt-Saarbrücken. On 4 August 1870 the French left Saarbrücken, driven away towards Metz in the Battle of Spicheren on 6 August 1870.

20th century

In 1909 the cities of Saarbrücken, St Johann and Malstatt-Burbach merged and formed the major city of Saarbrücken with a population of over 100,000.

During World War I, factories and railways in Saarbrücken were bombed by British forces. The Royal Naval Air Service raided Saarbrücken with 11 DH4s on 17 October 1917, and a week later with 9 HP11s.[17] The Royal Air Force raided Saarbrücken's railway station with 5 DH9s on 31 July 1918, on which occasion one DH9 crashed near the town centre.[18]

Saarbrücken became capital of the Saar territory established in 1920. Under the Treaty of Versailles (1919), the Saar coal mines were made the exclusive property of France for a period of 15 years as compensation for the destruction of French mines during the First World War. The treaty also provided for a plebiscite, at the end of the 15-year period, to determine the territory's future status, and in 1935 more than 90% of the electorate voted for reunification with Germany, while only 0.8% voted for unification with France. The remainder wanted to rejoin Germany but not while the Nazis were in power. This "status quo" group voted for maintenance of the League of Nations' administration. In 1935, the Saar territory rejoined Germany and formed a district under the name Saarland.

World War II

Saarbrücken was heavily bombed in World War II.[19] In total 1,234 people (1.1 percent of the population) in Saarbrücken were killed in bombing raids 1942–45.[20] 11,000 homes were destroyed and 75 percent of the city left in ruins.

The British Royal Air Force (RAF) raided Saarbrücken at least 10 times. Often employing area bombing, the RAF used total of at least 1495 planes to attack Saarbrücken, killing a minimum of 635 people and heavily damaging more than 8400 buildings, of which more than 7700 were completely destroyed, thus dehousing more than 50,000 people.[19] The first major raid on Saarbrücken was done by 291 aircraft of the RAF on 29 July 1942, targeting industrial facilities. Losing 9 aircraft, the bombers destroyed almost 400 buildings, damaging more than 300 others, and killed more than 150 people.[21] On 28 August 1942, 113 RAF planes raided Saarbrücken doing comparably little damage due to widely scattered bombing.[21] After the RAF mistakenly bombed Saarlouis instead of Saarbrücken on 1 September 1942, it raided Saarbrücken with 118 planes on 19 September 1942, causing comparably little damage as the bombing scattered to the west of Saarbrücken due to ground haze.[21] There were small raids with 28 Mosquitos[21] on 30 April 1944, with 33 Mosquitos[21] on 29 June 1944, and with just 2 Mosquitos[21] on 26 July 1944. At the request of the American Third Army, the RAF massively raided Saarbrücken on 5 October 1944, to destroy supply lines, especially the railway. The 531 Lancasters and 20 Mosquitos achieved these goals, but lost 3 Lancasters and destroyed large parts of Malstatt and nearly all of Alt-Saarbrücken.[21] From 13 to 14 January, the RAF raided Saarbrücken three times, targeting the railway yard. The attacks with 158, 274, and 134 planes, respectively, were very effective.[21]

The 8th US Air Force raided Saarbrücken at least 16 times, from 4 October 1943, to 9 November 1944. Targeting mostly the marshalling yards, a total of at least 2387 planes of the 8th. USAF killed a minimum of 543 people and heavily damaged more than 4400 buildings, of which more than 700 were completely destroyed, thus depriving more than 2300 people of shelter.[19] Donald J. Gott and William E. Metzger, Jr. were posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions during the bombing run on 9 November 1944.

On the ground, Saarbrücken was defended by the 347th Infantry Division commanded by Wolf-Günther Trierenberg in 1945.[22] The US 70th Infantry Division was tasked with punching through the Siegfried Line and taking Saarbrücken. As the fortifications were unusually strong, it first had to take the Siegfried Line fortifications on the French heights near Spicheren overlooking Saarbrücken. This Spichern-Stellung had been constructed in 1940 after the French had fallen back on the Maginot Line during the Phoney War. The 276th Infantry Regiment attacked Forbach on 19 February 1945, and a fierce battle ensued, halting the American advance at the rail-road tracks cutting through Forbach on 22 February 1945.[23] The 274th and 275th Infantry Regiments took Spicheren on 20 February 1945.[23] When the 274th Infantry Regiment captured the Spicheren Heights[23] on 23 February 1945, after a heavy battle on the previous day, the Germans counter-attacked for days, but by 27 February 1945, the heights were fully under American control.[24] A renewed attack on 3 March 1945, allowed units of the 70th Infantry Division to enter Stiring-Wendel and the remainder of Forbach. By 5 March 1945, all of Forbach and major parts of Stiring-Wendel had been taken. However, fighting for Stiring-Wendel, especially for the Simon mine, continued for days.[23] After the German defenders of Stiring-Wendel fell back to Saarbrücken on 12 and 13 March 1945,[25] the 70th Infantry Division still faced a strong segment of the Siegfried Line, which had been reinforced[26] around Saarbrücken as late as 1940. After having the German troops south of the Saar fall back across the Saar at night, the German defenders of Saarbrücken retreated early on 20 March 1945. The 70th Infantry Division flanked Saarbrücken by crossing the Saar north-west of Saarbrücken. The 274th Infantry Regiment entered Saarbrücken on 20 March 1945, fully occupying it the following day, thus ending the war for Saarbrücken.[25]

After World War II

In 1945, Saarbrücken temporarily became part of the French Zone of Occupation. In 1947, France created the nominally politically independent Saar Protectorate and merged it economically with France to exploit the area's vast coal reserves. Saarbrücken became capital of the new Saar state. A referendum in 1955 came out with over two-thirds of the voters rejecting an independent Saar state. The area rejoined the Federal Republic of Germany on 1 January 1957, sometimes called Kleine Wiedervereinigung (little reunification). Economic reintegration would, however, take many more years. Saarbrücken became capital of the Bundesland (federal state) Saarland. After the administrative reform of 1974, the city had a population of more than 200,000.

From 1990 to 1993, students and an arts professor from the town first secretly, then officially, created an invisible memorial to Jewish cemeteries. It is located on the fore-court of the Saarbrücken Castle.

On 9 March 1999 at 4:40 am, there was a bomb attack on the controversial Wehrmachtsausstellung exhibition next to Saarbrücken Castle, resulting in minor damage to the Volkshochschule building housing the exhibition and the adjoining Schlosskirche church; this attack did not cause any injuries.[27]

Geography

Climate

Climate in this area has mild differences between highs and lows, and there is adequate rainfall year-round. The Köppen Climate Classification subtype for this climate is "Cfb" (Marine West Coast Climate/Oceanic climate).[28]

| Climate data for Saarbrücken | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 2.6 (36.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

8.5 (47.3) |

12.7 (54.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

20.2 (68.4) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.1 (71.8) |

18.8 (65.8) |

13.5 (56.3) |

7.1 (44.8) |

3.6 (38.5) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.0 (28.4) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

1.1 (34.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

7.8 (46.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

6.2 (43.2) |

1.6 (34.9) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

5.2 (41.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 69 (2.7) |

59 (2.3) |

66 (2.6) |

60 (2.4) |

81 (3.2) |

83 (3.3) |

72 (2.8) |

73 (2.9) |

62 (2.4) |

71 (2.8) |

84 (3.3) |

83 (3.3) |

863 (34.0) |

| Average precipitation days | 13 | 10 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 130 |

| Average rainy days | 12.2 | 9.8 | 11.3 | 10.0 | 11.0 | 11.3 | 9.3 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 11.2 | 11.7 | 12.7 | 128.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 88 | 83 | 77 | 71 | 71 | 72 | 70 | 73 | 78 | 84 | 87 | 88 | 79 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 44 | 77 | 119 | 171 | 201 | 214 | 234 | 212 | 153 | 100 | 48 | 34 | 1,607 |

| Source 1: Wetterkontor[29] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst[30] World Weather Information Service[31] | |||||||||||||

Region

Some of the closest cities are Trier, Luxembourg, Nancy, Metz, Kaiserslautern, Karlsruhe and Mannheim. Saarbrücken is connected by the city's public transport network to the town of Sarreguemines in France, and to the neighboring town of Völklingen, where the old steel works were the first industrial monument to be declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1994 – the Völklinger Hütte.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 105,089 | — |

| 1919 | 110,623 | +5.3% |

| 1927 | 125,020 | +13.0% |

| 1935 | 129,085 | +3.3% |

| 1946 | 89,709 | −30.5% |

| 1961 | 130,705 | +45.7% |

| 1970 | 127,989 | −2.1% |

| 1987 | 188,702 | +47.4% |

| 2011 | 175,853 | −6.8% |

| 2018 | 180,741 | +2.8% |

| source:[32] | ||

| Largest groups of foreign residents[33] | |

| Country of birth | Population (2014) |

|---|---|

| 3,851 | |

| 2,292 | |

| 2,245 | |

| 1,555 | |

| 1,000 | |

Infrastructure

The city is served by Saarbrücken Airport (SCN), and since June 2007 ICE high speed train services along the LGV Est line provide high speed connections to Paris from Saarbrücken Hauptbahnhof. Saarbrücken's Saarbahn (modelled on the Karlsruhe model light rail) crosses the French–German border, connecting to the French city of Sarreguemines.

Science and education

Saarbrücken is also the home of the main campus of Saarland University (Universität des Saarlandes). There are several research institutes and centres on or near the campus, including:

- the Max Planck Institute for Informatics,

- the Max Planck Institute for Software Systems,

- the Helmholtz Institute for Pharmaceutical Research Saarland (HIPS),[34]

- the Fraunhofer Institute for Non-destructive Testing,

- the German Research Centre for Artificial Intelligence,

- the Center for Bioinformatics,

- the Europa-Institut,

- the Korea Institute of Science and Technology Europe Research Society,

- the Leibniz Institute for New Materials (INM), and

- the Intel Visual Computing Institute,[35]

- the CISPA Helmholtz Center for Information Security,[36] [37]

- the Society for Environmentally Compatible Process Technology,

- the Institut für Angewandte Informationsforschung for applied linguistics,

- several institutes focusing on transfer of technology between academia and companies, and the Science Park Saar startup incubator.

The Saarland University also has a Centre Juridique Franco-Allemand, offering a French and a German law degree program.

The Botanischer Garten der Universität des Saarlandes (a botanical garden) was closed in 2016 due to budget cuts.

The main campus of the Saarland University also houses the office of the Schloss Dagstuhl – Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik computer science research and meeting center.

Furthermore, Saarbrücken houses the administration of the Franco-German University (Deutsch-Französische Hochschule), a French-German cooperation of 180 institutions of tertiary education mainly from France and Germany but also from Bulgaria, Canada, Spain, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Great Britain, Russia and Switzerland, which offers bi-national French-German degree programs and doctorates as well as tri-national degree programs.

Saarbrücken houses several other institutions of tertiary education as well:

- the University of Applied Sciences Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft des Saarlandes,

- the University of Arts Hochschule der Bildenden Künste Saar,

- the University of Music Hochschule für Musik Saar, and

- the private Fachhochschule for health promotion and physical fitness Deutsche Hochschule für Prävention und Gesundheitsmanagement

- The Höhere Berufsfachschule für Wirtschaftsinformatik (HBFS-WI) providing higher vocational education and awarding the degree "Staatlich geprüfte(r) Wirtschaftsinformatiker(in)" (English: "state-examined business data processing specialist")

Saarbrücken also houses a Volkshochschule.

With the end of coal mining in the Saar region, Saarbrücken's Fachhochschule for mining, the Fachhochschule für Bergbau Saar, was closed at the beginning of the 21st century. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Trier's Katholische Hochschule für Soziale Arbeit, a Fachhochschule for social work, was closed in 2008 for cost cutting reasons. The Saarland's Fachhochschule for administrative personnel working for the government, the Fachhochschule für Verwaltung des Saarlandes, was moved from Saarbrücken to Göttelborn in 2012.

Saarbrücken houses several institutions of primary and secondary education. Notable is the Saarland's oldest grammar school, the Ludwigsgymnasium, which was founded in 1604 as a latin school. The building of Saarbrücken's bi-lingual French-German Deutsch-Französisches Gymnasium, founded in 1961 and operating as a laboratory school under the Élysée Treaty, also houses the École française de Sarrebruck et Dilling, a French primary school which offers bi-lingual German elements. Together with several Kindergartens offering bi-lingual French-German education, Saarbrücken thus offers a full bi-lingual French-German formal education.

Sport

The city is home to several different teams, most notable of which is association football team based at the Ludwigsparkstadion, 1. FC Saarbrücken, which also has a reserve team and a women's section. In the past a top-flight team, twice the country's vice-champions, and participant in European competitions, the club draws supporters from across the region.

Lower league SV Saar 05 Saarbrücken is the other football team in the city.

The Saarland Hurricanes are one of the top American football teams in the country, with its junior team winning the German Junior Bowl in 2013.

Various sporting events are held at the Saarlandhalle, most notable of which was the badminton Bitburger Open Grand Prix Gold, part of the BWF Grand Prix Gold and Grand Prix tournaments, held in 2013 and 2012.

International relations

Saarbrücken is a fellow member of the QuattroPole union of cities, along with Luxembourg, Metz, and Trier (formed by cities from three neighbouring countries: Germany, Luxembourg and France).

Twin towns – Sister cities

Saarbrücken is twinned with:

Saarbrücken has a Städtefreundschaft (city friendship) with:

Some boroughs of Saarbrücken are also twinned:

| Borough | Twinned with |

|---|---|

| Dudweiler |

|

| Altenkessel |

|

Notable people

- Edmond Pottier (1855–1934), French art historian and archaeologist

- Carl Röchling (1855–1920), painter and illustrator

- Peter Kurtz (1881–1977), native of Saarbrücken; introduced the music of Peer Gynt to America

- Walther Poppelreuter (1886–1939), neurologist and psychiatrist

- Alfred Sturm (1888–1962), German lieutenant-general in the Second World War

- Margot Benary-Isbert (1889–1979), author

- Hans Wagner (1896–1967), German general lieutenant in the Second World War

- Peter Altmeier (1899–1977), politician

- Max Ophüls (1902–1957), film director

- Wolfgang Staudte (1906–1984), film director

- Walter Schellenberg (1910–1952), Senior German SS officer (head of Foreign intelligence)

.jpg)

- Gerhard Schröder (1910–1989), politician (CDU)

- Otto Steinert (1915–1978), photographer

- Frédéric Back (1924–2013), Canadian animator

- Michel Antoine (1925–2015), French historian

- Frederic Vester (1925–2003), biochemist

- Hannelore Baron (1926–1987), collage and assemblage artist, emigrated to the United States in 1941

- Gerd Peehs (born 1942), football player

- Sandra Cretu (born 1962), singer

- Claudia Kohde-Kilsch (born 1963), tennis player

- Nicole (born 1964), singer

- Manfred Trenz (born 1965), game designer

- Saskia Vester (born 1959), actress and author

- Lisa Klein (born 1996), cyclist

Honorary citizens

- Willi Graf (1918–1943), member of the White Rose resistance group

- Tzvi Avni (born Hermann Jakob Steinke, 1927), Israeli composer[43]

- Max Braun (1892–1945), politician and journalist, renown for his fight against Nazism, especially over the Saar status.[44]

Gallery

- Town Hall St. Johann

Stiftskirche St. Arnual

Stiftskirche St. Arnual.jpg) Schlosskirche St. Nikolaus

Schlosskirche St. Nikolaus Friedenskirche, seen from Ludwigsplatz

Friedenskirche, seen from Ludwigsplatz St. John's Basilica

St. John's Basilica- Ludwigskirche

Alte Brücke (Old Bridge)

Alte Brücke (Old Bridge) Staatstheater (Theatre)

Staatstheater (Theatre) St. Michael

St. Michael Saarbahn tramway

Saarbahn tramway The central station

The central station

Saarbrücken, Harbour Road

Saarbrücken, Harbour Road Bürgerpark

Bürgerpark Campus of the Saarland University

Campus of the Saarland University

References

- Notes

- "Saarland.de – Amtliche Einwohnerzahlen Stand 31.12.2018" (PDF). Statistisches Amt des Saarlandes (in German). June 2019.

- "Fläche, Bevölkerung in den Gemeinden am 30.06.2017 nach Geschlecht, Einwohner je km 2 und Anteil an der Gesamtbevölkerung (Basis Zensus 2011)" (PDF). Saarland.de.

- "Euro District Saar-Moselle". saarmoselle.org.

- "Saarbrücken". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- "Saarbrücken". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- "Saarbrücken". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- "Start | Landeshauptstadt Saarbrücken". Saarbruecken.de (in French and German).

- Dr. Andreas Neumann. "Saarbrücken hat nichts mit Brücken zu tun?" (in German). Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Krebs, Gerhild; Hudemann, Rainer; Marcus Hahn (2009). "Brücken an der mittleren Saar und ihren Nebenflüssen [Bridges in the middle Saar and its tributaries]". Stätten grenzüberschreitender Erinnerung – Spuren der Vernetzung des Saar-Lor-Lux-Raumes im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert [Places of transnational memory – traces of crosslinking of the Saar-Lor-Lux area in the 19th and 20th centuries] (in German) (3rd ed.). Saarbrücken: Johannes Großmann. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Sander, Eckart (1999), "Meine Geburt war das erste meiner Mißgeschicke", Stadtluft macht frei (in German), Stadtverband Saarbrücken, Pressereferat, pp. 8–9, ISBN 3-923405-10-3

- "Chronik von Saarbrücken" (in German). Landeshauptstadt Saarbrücken. Archived from the original on 6 December 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- "Das Römerkastell in Saarbrücken" (in German). Interessengemeinschaft Warndt und Rosseltalbahn (IGWRB) e. V. Archived from the original on 13 February 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- "Röerkastell in Saarbrücken". Saarlandbilder (in German). Andreas Rockstein. 20 January 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Jan Selmer (2005). "Ausgrabungen im Kreuzgangbereich des ehem. Stiftes St. Arnual, Saarbrücken 1996–2004" (in German). Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Mithras-Heiligtum Saarbrücken" (in German). Tourismus Zentrale Saarland GmbH. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- Behringer, Wolfgang; Clemens, Gabriele (20 July 2011). "Hochmittelalterlicher Landesausbau". Geschichte des Saarlandes [History of the Saarland] (in German). München: C.H.Beck. p. 21. ISBN 978-3-406-62520-6. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Development of the Strategic Bomber". RAF History – Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. 13 March 2006. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- "No. 99 Squadron". RAF History – Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. 13 March 2006. Archived from the original on 1 March 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- Klaus Zimmer (27 July 2012). "air raids". The results of the air war 1939–1945 in the Saarland. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- After the Battle Magazine, Issue 170, November 2015, page 34

- "Campaign Diary". RAF History – Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. UK Crown. 13 March 2006. Archived from the original on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

1942: July, August, September,

1944: April, June, July, October,

1945: January - After the Battle Magazine, Issue 170, November 2015, page 36

- 70th Regional Readiness Command (10 November 2004). "Abbreviated History of the 70th Infantry Division" (PDF). taken from "The 50th Anniversary program book of the 70th Division (Training)". Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- Charlie Pence (1 February 2013). "The Battle for Spicheren Heights". taken from "Trailblazer" magazine, Fall 1997, pp. 10–12. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- Headquarters 274th Infantry – APO 461 US Army. "Period from 1 Mar 1945 to 31 Mar 1945". Narrative Report of Operations. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- "Die Höckerlinie in St. Arnual". Operation Linsenspalter- Der Westwall im Saarland (in German). 15 May 2005. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- Karl-Otto Sattler (10 March 1999). "Sprengstoffanschlag auf Wehrmachtsausstellung". Berliner Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- Climate Summary for Saarbrücken from Weatherbase.com

- "Klima Deutschland, Saarbrücken". Retrieved 22 June 2014.

- "Sonnenscheindauer: langjährige Mittelwerte 1981 – 2010". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2014.

- "Weather Information for Saarbruecken". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- Link

- Waespi-Oeß, Rainer. "Die Bevölkerung Saarbrückens im Jahr 2013". Amt für Entwicklungsplanung, Statistik und Wahlen. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research : About HIPS". Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- "Intel Visual Computing Institute: Bridging Real and Virtual Worlds". Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- "About CISPA". Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "Helmholtz Centers". Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "Town Twinnings". Landeshauptstadt Saarbrücken. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- "Our twin cities – Cottbus". cottbus.de/. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- "Tbilisi Sister Cities". Tbilisi City Hall. Tbilisi Municipal Portal. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- "Städtepartnerschaften" (in German). Landeshauptstadt Saarbrücken. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- Tauchert, Wolfgang. "Saarbrücken – Diriamba". Saarland:Parnterschaftsprojekte (in German). Staatskanzlei des Saarlandes. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- "Tzvi Avni Saarbrücker Ehrenbürger" (in German). Landeshauptstadt Saarbrücken. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "Neuer Ehrenbürger Max Braun" (in German). Landeshauptstadt Saarbrücken. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- Non-English Wikipedia links

- Saarbrücken#Stadtname (in German). Retrieved 11 June 2013

- Dudweiler#Partnerschaften/Patenschaft (in German). Retrieved 11 June 2013

- Duttweiler (Neustadt)#Politik (in German). Retrieved 11 June 2013

- Saarbrücken#Städtepartnerschaften (in German). Retrieved 11 June 2013

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Saarbrücken. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saarbrücken. |

- Official website

- Official website (in German)

- Saarbrücken-Ensheim Airport

- Saarbrücken-Ensheim Airport (in German)