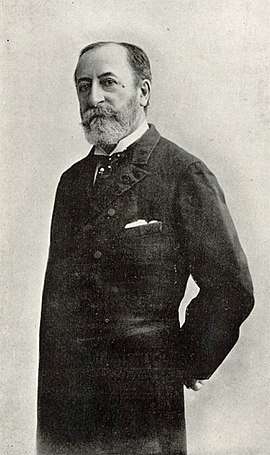

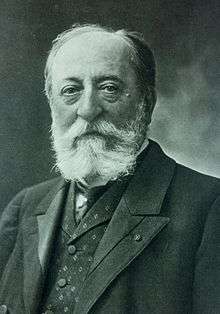

Camille Saint-Saëns

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns (French: [ʃaʁl kamij sɛ̃ sɑ̃(s)];[n 1] 9 October 1835 – 16 December 1921) was a French composer, organist, conductor and pianist of the Romantic era. His best-known works include Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso (1863), the Second Piano Concerto (1868), the First Cello Concerto (1872), Danse macabre (1874), the opera Samson and Delilah (1877), the Third Violin Concerto (1880), the Third ("Organ") Symphony (1886) and The Carnival of the Animals (1886).

Saint-Saëns was a musical prodigy; he made his concert debut at the age of ten. After studying at the Paris Conservatoire he followed a conventional career as a church organist, first at Saint-Merri, Paris and, from 1858, La Madeleine, the official church of the French Empire. After leaving the post twenty years later, he was a successful freelance pianist and composer, in demand in Europe and the Americas.

As a young man, Saint-Saëns was enthusiastic for the most modern music of the day, particularly that of Schumann, Liszt and Wagner, although his own compositions were generally within a conventional classical tradition. He was a scholar of musical history, and remained committed to the structures worked out by earlier French composers. This brought him into conflict in his later years with composers of the impressionist and dodecaphonic schools of music; although there were neoclassical elements in his music, foreshadowing works by Stravinsky and Les Six, he was often regarded as a reactionary in the decades around the time of his death.

Saint-Saëns held only one teaching post, at the École de Musique Classique et Religieuse in Paris, and remained there for less than five years. It was nevertheless important in the development of French music: his students included Gabriel Fauré, among whose own later pupils was Maurice Ravel. Both of them were strongly influenced by Saint-Saëns, whom they revered as a genius.

Life

Early life

Saint-Saëns was born in Paris, the only child of Jacques-Joseph-Victor Saint-Saëns (1798–1835), an official in the French Ministry of the Interior, and Françoise-Clémence, née Collin.[5] Victor Saint-Saëns was of Norman ancestry, and his wife was from an Haute-Marne family;[n 2] their son, born in the Rue du Jardinet in the 6th arrondissement of Paris, and baptised at the nearby church of Saint-Sulpice, always considered himself a true Parisian.[10] Less than two months after the christening, Victor Saint-Saëns died of consumption (tuberculosis) on the first anniversary of his marriage.[11] The young Camille was taken to the country for the sake of his health, and for two years lived with a nurse at Corbeil, 29 kilometres (18 mi) to the south of Paris.[12]

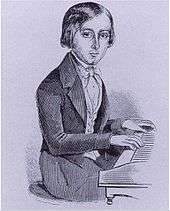

When Saint-Saëns was brought back to Paris he lived with his mother and her widowed aunt, Charlotte Masson. Before he was three years old he displayed perfect pitch and enjoyed picking out tunes on the piano.[13] His great-aunt taught him the basics of pianism, and when he was seven he became a pupil of Camille-Marie Stamaty, a former pupil of Friedrich Kalkbrenner.[14] Stamaty required his students to play while resting their forearms on a bar situated in front of the keyboard, so that all the pianist's power came from the hands and fingers rather than the arms, which, Saint-Saëns later wrote, was good training.[15] Clémence Saint-Saëns, well aware of her son's precocious talent, did not wish him to become famous too young. The music critic Harold C. Schonberg wrote of Saint-Saëns in 1969, "It is not generally realized that he was the most remarkable child prodigy in history, and that includes Mozart."[16] The boy gave occasional performances for small audiences from the age of five, but it was not until he was ten that he made his official public debut, at the Salle Pleyel, in a programme that included Mozart's Piano Concerto in B♭ (K450), and Beethoven's Third Piano Concerto.[5] Through Stamaty's influence, Saint-Saëns was introduced to the composition professor Pierre Maleden and the organ teacher Alexandre Pierre François Boëly. From the latter he acquired a lifelong love of the music of Bach, which was then little known in France.[17]

As a schoolboy Saint-Saëns was outstanding in many subjects. In addition to his musical prowess, he distinguished himself in the study of French literature, Latin and Greek, divinity, and mathematics. His interests included philosophy, archaeology and astronomy, of which, particularly the last, he remained a talented amateur in later life.[5][n 3]

In 1848, at the age of thirteen, Saint-Saëns was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire, France's foremost music academy. The director, Daniel Auber, had succeeded Luigi Cherubini in 1842, and brought a more relaxed regime than that of his martinet predecessor, though the curriculum remained conservative.[20][n 4] Students, even outstanding pianists like Saint-Saëns, were encouraged to specialise in organ studies, because a career as a church organist was seen to offer more opportunities than that of a solo pianist.[22] His organ professor was François Benoist, whom Saint-Saëns considered a mediocre organist but a first-rate teacher;[23] his pupils included Adolphe Adam, César Franck, Charles Alkan, Louis Lefébure-Wély and Georges Bizet.[24] In 1851 Saint-Saëns won the Conservatoire's top prize for organists, and in the same year he began formal composition studies.[n 5] His professor was a protégé of Cherubini, Fromental Halévy, whose pupils included Charles Gounod and Bizet.[26]

Saint-Saëns's student compositions included a symphony in A major (1850) and a choral piece, Les Djinns (1850), after an eponymous poem by Victor Hugo.[27] He competed for France's premier musical award, the Prix de Rome, in 1852 but was unsuccessful. Auber believed that the prize should have gone to Saint-Saëns, considering him to have more promise than the winner, Léonce Cohen, who made little mark during the rest of his career.[22] In the same year Saint-Saëns had greater success in a competition organised by the Société Sainte-Cécile, Paris, with his Ode à Sainte-Cécile, for which the judges unanimously voted him the first prize.[28] The first piece the composer acknowledged as a mature work and gave an opus number was Trois Morceaux for harmonium (1852).[n 6]

Early career

On leaving the Conservatoire in 1853, Saint-Saëns accepted the post of organist at the ancient Parisian church of Saint-Merri near the Hôtel de Ville. The parish was substantial, with 26,000 parishioners; in a typical year there were more than two hundred weddings, the organist's fees from which, together with fees for funerals and his modest basic stipend, gave Saint-Saëns a comfortable income.[30] The organ, the work of François-Henri Clicquot, had been badly damaged in the aftermath of the French Revolution and imperfectly restored. The instrument was adequate for church services but not for the ambitious recitals that many high-profile Parisian churches offered.[31] With enough spare time to pursue his career as a pianist and composer, Saint-Saëns composed what became his opus 2, the Symphony in E♭ (1853).[27] This work, with military fanfares and augmented brass and percussion sections, caught the mood of the times in the wake of the popular rise to power of Napoleon III and the restoration of the French Empire.[32] The work brought the composer another first prize from the Société Sainte-Cécile.[33]

Among the musicians who were quick to spot Saint-Saëns's talent were the composers Gioachino Rossini, Hector Berlioz and Franz Liszt, and the influential singer Pauline Viardot, who all encouraged him in his career.[5] In early 1858 Saint-Saëns moved from Saint-Merri to the high-profile post of organist of La Madeleine, the official church of the Empire; Liszt heard him playing there and declared him the greatest organist in the world.[34]

Although in later life he had a reputation for outspoken musical conservatism, in the 1850s Saint-Saëns supported and promoted the most modern music of the day, including that of Liszt, Robert Schumann and Richard Wagner.[5] Unlike many French composers of his own and the next generation, Saint-Saëns, for all his enthusiasm for and knowledge of Wagner's operas, was not influenced by him in his own compositions.[35][36] He commented, "I admire deeply the works of Richard Wagner in spite of their bizarre character. They are superior and powerful, and that is sufficient for me. But I am not, I have never been, and I shall never be of the Wagnerian religion."[36]

1860s: Teacher and growing fame

In 1861 Saint-Saëns accepted his only post as a teacher, at the École de Musique Classique et Religieuse, Paris, which Louis Niedermeyer had established in 1853 to train first-rate organists and choirmasters for the churches of France. Niedermeyer himself was professor of piano; when he died in March 1861, Saint-Saëns was appointed to take charge of piano studies. He scandalised some of his more austere colleagues by introducing his students to contemporary music, including that of Schumann, Liszt and Wagner.[37] His best-known pupil, Gabriel Fauré, recalled in old age:

After allowing the lessons to run over, he would go to the piano and reveal to us those works of the masters from which the rigorous classical nature of our programme of study kept us at a distance and who, moreover, in those far-off years, were scarcely known. ... At the time I was 15 or 16, and from this time dates the almost filial attachment ... the immense admiration, the unceasing gratitude I [have] had for him, throughout my life.[38]

Saint-Saëns further enlivened the academic regime by writing, and composing incidental music for, a one-act farce performed by the students (including André Messager).[39] He conceived his best-known piece, The Carnival of the Animals, with his students in mind, but did not finish composing it until 1886, more than twenty years after he left the Niedermeyer school.[40]

In 1864 Saint-Saëns caused some surprise by competing a second time for the Prix de Rome. Many in musical circles were puzzled by his decision to enter the competition again, now that he was establishing a reputation as a soloist and composer. He was once more unsuccessful. Berlioz, one of the judges, wrote:

We gave the Prix de Rome the other day to a young man who wasn't expecting to win it and who went almost mad with joy. We were all expecting the prize to go to Camille Saint-Saëns, who had the strange notion of competing. I confess I was sorry to vote against a man who is truly a great artist and one who is already well known, practically a celebrity. But the other man, who is still a student, has that inner fire, inspiration, he feels, he can do things that can't be learnt and the rest he'll learn more or less. So I voted for him, sighing at the thought of the unhappiness that this failure must cause Saint-Saëns. But, whatever else, one must be honest.[41]

According to the musical scholar Jean Gallois, it was apropos of this episode that Berlioz made his well-known bon mot about Saint-Saëns, "He knows everything, but lacks inexperience" ("Il sait tout, mais il manque d'inexpérience").[42][n 7] The winner, Victor Sieg, had a career no more notable than that of the 1852 winner, but Saint-Saëns's biographer Brian Rees speculates that the judges may "have been seeking signs of genius in the midst of tentative effort and error, and considered that Saint-Saëns had reached his summit of proficiency".[45] The suggestion that Saint-Saëns was more proficient than inspired dogged his career and posthumous reputation. He himself wrote, "Art is intended to create beauty and character. Feeling only comes afterwards and art can very well do without it. In fact, it is very much better off when it does."[46] The biographer Jessica Duchen writes that he was "a troubled man who preferred not to betray the darker side of his soul".[6] The critic and composer Jeremy Nicholas observes that this reticence has led many to underrate the music; he quotes such slighting remarks as "Saint-Saëns is the only great composer who wasn't a genius", and "Bad music well written".[47]

While teaching at the Niedermeyer school Saint-Saëns put less of his energy into composing and performing, but after he left in 1865 he pursued both aspects of his career with vigour.[48] In 1867 his cantata Les noces de Prométhée beat more than a hundred other entries to win the composition prize of the Grande Fête Internationale in Paris, for which the jury included Auber, Berlioz, Gounod, Rossini and Giuseppe Verdi.[5][49][n 8] In 1868 he premiered the first of his orchestral works to gain a permanent place in the repertoire, his Second Piano Concerto.[27] Playing this and other works he became a noted figure in the musical life of Paris and other cities in France and abroad during the 1860s.[5]

1870s: War, marriage and operatic success

In 1870, concerned at the dominance of German music and the lack of opportunity for young French composers to have their works played, Saint-Saëns and Romain Bussine, professor of singing at the Conservatoire, discussed the founding of a society to promote new French music.[51] Before they could take the proposal further, the Franco-Prussian War broke out. Saint-Saëns served in the National Guard during the war. During the brief but bloody Paris Commune that followed, his superior at the Madeleine, the Abbé Deguerry, was murdered by rebels;[52] Saint-Saëns was fortunate to escape to temporary exile in England where he arrived in May 1871.[51] With the help of George Grove and others he supported himself while there, giving recitals.[53] Returning to Paris in the same year, he found that anti-German sentiments had considerably enhanced support for the idea of a pro-French musical society.[n 9] The Société Nationale de Musique, with its motto, "Ars Gallica", had been established in February 1871, with Bussine as president, Saint-Saëns as vice-president and Henri Duparc, Fauré, Franck and Jules Massenet among its founder-members.[55]

As an admirer of Liszt's innovative symphonic poems, Saint-Saëns enthusiastically adopted the form; his first "poème symphonique" was Le Rouet d'Omphale (1871), premiered at a concert of the Sociéte Nationale in January 1872.[56] In the same year, after more than a decade of intermittent work on operatic scores, Saint-Saëns finally had one of his operas staged. La princesse jaune ("The Yellow Princess"), a one-act, light romantic piece, was given at the Opéra-Comique, Paris in June. It ran for five performances.[57]

Throughout the 1860s and early 1870s, Saint-Saëns had continued to live a bachelor existence, sharing a large fourth-floor flat in the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré with his mother. In 1875, he surprised many by marrying.[6][n 10] The groom was approaching forty and his bride was nineteen; she was Marie-Laure Truffot, the sister of one of the composer's pupils.[58] The marriage was not a success. In the words of the biographer Sabina Teller Ratner, "Saint-Saëns's mother disapproved, and her son was difficult to live with".[5] Saint-Saëns and his wife moved to the Rue Monsieur-le-Prince, in the Latin Quarter; his mother moved with them.[59] The couple had two sons, both of whom died in infancy. In 1878, the elder, André, aged two, fell from a window of the flat and was killed;[60] the younger, Jean-François, died of pneumonia six weeks later, aged six months. Saint-Saëns and Marie-Laure continued to live together for three years, but he blamed her for André's accident; the double blow of their loss effectively destroyed the marriage.[6]

For a French composer of the 19th century, opera was seen as the most important type of music.[61] Saint-Saëns's younger contemporary and rival, Massenet, was beginning to gain a reputation as an operatic composer, but Saint-Saëns, with only the short and unsuccessful La princesse jaune staged, had made no mark in that sphere.[62][n 11] In February 1877, he finally had a full-length opera staged. His four-act "drame lyricque", Le timbre d'argent ("The Silver Bell"), to Jules Barbier's and Michel Carré's libretto, reminiscent of the Faust legend, had been in rehearsal in 1870, but the outbreak of war halted the production.[66] The work was eventually presented by the Théâtre Lyrique company of Paris; it ran for eighteen performances.[67]

The dedicatee of the opera, Albert Libon, died three months after the premiere, leaving Saint-Saëns a large legacy "To free him from the slavery of the organ of the Madeleine and to enable him to devote himself entirely to composition".[68] Saint-Saëns, unaware of the imminent bequest, had resigned his position shortly before his friend died. He was not a conventional Christian, and found religious dogma increasingly irksome;[n 12] he had become tired of the clerical authorities' interference and musical insensitivity; and he wanted to be free to accept more engagements as a piano soloist in other cities.[70] After this he never played the organ professionally in a church service, and rarely played the instrument at all.[71] He composed a Messe de Requiem in memory of his friend, which was performed at Saint-Sulpice to mark the first anniversary of Libon's death; Charles-Marie Widor played the organ and Saint-Saëns conducted.[68]

In December 1877, Saint-Saëns had a more solid operatic success, with Samson et Dalila, his one opera to gain and keep a place in the international repertoire. Because of its biblical subject, the composer had met many obstacles to its presentation in France, and through Liszt's influence the premiere was given at Weimar in a German translation. Although the work eventually became an international success it was not staged at the Paris Opéra until 1892.[61]

Saint-Saëns was a keen traveller. From the 1870s until the end of his life he made 179 trips to 27 countries. His professional engagements took him most often to Germany and England; for holidays, and to avoid Parisian winters which affected his weak chest, he favoured Algiers and various places in Egypt.[72]

1880s: International figure

Saint-Saëns was elected to the Institut de France in 1881, at his second attempt, having to his chagrin been beaten by Massenet in 1878.[73] In July of that year he and his wife went to the Auvergnat spa town of La Bourboule for a holiday. On 28 July he disappeared from their hotel, and a few days later his wife received a letter from him to say that he would not be returning. They never saw each other again. Marie Saint-Saëns returned to her family, and lived until 1950, dying near Bordeaux at the age of ninety-five.[74] Saint-Saëns did not divorce his wife and remarry, nor did he form any later intimate relationship with a woman. Rees comments that although there is no firm evidence, some biographers believe that Saint-Saëns was more attracted to his own sex than to women.[75][n 10] After the death of his children and collapse of his marriage, Saint-Saëns increasingly found a surrogate family in Fauré and his wife, Marie, and their two sons, to whom he was a much-loved honorary uncle.[80] Marie told him, "For us you are one of the family, and we mention your name ceaselessly here."[81]

In the 1880s Saint-Saëns continued to seek success in the opera house, an undertaking made the more difficult by an entrenched belief among influential members of the musical establishment that it was unthinkable that a pianist, organist and symphonist could write a good opera.[82] He had two operas staged during the decade, the first being Henry VIII (1883) commissioned by the Paris Opéra. Although the libretto was not of his choosing, Saint-Saëns, normally a fluent, even facile composer,[n 13] worked at the score with unusual diligence to capture a convincing air of 16th-century England.[82] The work was a success, and was frequently revived during the composer's lifetime.[61] When it was produced at Covent Garden in 1898, The Era commented that though French librettists generally "make a pretty hash of British history", this piece was "not altogether contemptible as an opera story".[84]

The open-mindedness of the Société Nationale had hardened by the mid-1880s into a dogmatic adherence to Wagnerian methods favoured by Franck's pupils, led by Vincent d'Indy. They had begun to dominate the organisation and sought to abandon its "Ars Gallica" ethos of commitment to French works. Bussine and Saint-Saëns found this unacceptable, and resigned in 1886.[54][n 14] Having long pressed the merits of Wagner on a sometimes sceptical French public, Saint-Saëns was now becoming worried that the German's music was having an excessive impact on young French composers. His increasing caution towards Wagner developed in later years into stronger hostility, directed as much at Wagner's political nationalism as at his music.[54]

By the 1880s Saint-Saëns was an established favourite with audiences in England, where he was widely regarded as the greatest living French composer.[86] In 1886 the Philharmonic Society of London commissioned what became one of his most popular and respected works, the Third ("Organ") Symphony. It was premiered in London at a concert in which Saint-Saëns appeared as conductor of the symphony and as soloist in Beethoven's Fourth Piano Concerto, conducted by Sir Arthur Sullivan.[87] The success of the symphony in London was considerable, but was surpassed by the ecstatic welcome the work received at its Paris premiere early the following year.[88] Later in 1887 Saint-Saëns's "drame lyrique" Proserpine opened at the Opéra-Comique. It was well received and seemed to be heading for a substantial run when the theatre burnt down within weeks of the premiere and the production was lost.[82]

In December 1888 Saint-Saëns's mother died.[89] He felt her loss deeply, and was plunged into depression and insomnia, even contemplating suicide.[90] He left Paris and stayed in Algiers, where he recuperated until May 1889, walking and reading but unable to compose.[91]

1890s: Marking time

During the 1890s Saint-Saëns spent much time on holiday, travelling overseas, composing less and performing more infrequently than before. A planned visit to perform in Chicago fell through in 1893.[92] He wrote one opera, the comedy Phryné (1893), and together with Paul Dukas helped to complete Frédégonde (1895) an opera left unfinished by Ernest Guiraud, who died in 1892. Phryné was well received, and prompted calls for more comic operas at the Opéra-Comique, which had latterly been favouring grand opera.[93] His few choral and orchestral works from the 1890s are mostly short; the major concert pieces from the decade were the single movement fantasia Africa (1891) and his Fifth ("Egyptian") Piano Concerto, which he premiered at a concert in 1896 marking the fiftieth anniversary of his début at the Salle Pleyel in 1846.[94] Before playing the concerto he read out a short poem he had written for the event, praising his mother's tutelage and his public's long support.[95]

Among the concerts that Saint-Saëns undertook during the decade was one at Cambridge in June 1893, when he, Bruch and Tchaikovsky performed at an event presented by Charles Villiers Stanford for the Cambridge University Musical Society, marking the award of honorary degrees to all three visitors.[96] Saint-Saëns greatly enjoyed the visit, and even spoke approvingly of the college chapel services: "The demands of English religion are not excessive. The services are very short, and consist chiefly of listening to good music extremely well sung, for the English are excellent choristers".[97] His mutual regard for British choirs continued for the rest of his life, and one of his last large-scale works, the oratorio The Promised Land, was composed for the Three Choirs Festival of 1913.[98]

1900–21: Last years

In 1900, after ten years without a permanent home in Paris, Saint-Saëns took a flat in the rue de Courcelles, not far from his old residence in the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. This remained his home for the rest of his life.[99] He continued to travel abroad frequently, but increasingly often to give concerts rather than as a tourist. He revisited London, where he was always a welcome visitor, went to Berlin, where until the First World War, he was greeted with honour, and travelled in Italy, Spain, Monaco and provincial France.[99] In 1906 and 1909 he made highly successful tours of the United States, as a pianist and conductor.[100] In New York on his second visit he premiered his "Praise ye the Lord" for double choir, orchestra and organ, which he composed for the occasion.[101]

Despite his growing reputation as a musical reactionary, Saint-Saëns was, according to Gallois, probably the only French musician who travelled to Munich to hear the premiere of Mahler's Eighth Symphony in 1910.[102] Nonetheless, by the 20th century Saint-Saëns had lost much of his enthusiasm for modernism in music. Though he strove to conceal it from Fauré, he did not understand or like the latter's opera Pénélope (1913), of which he was the dedicatee.[103] In 1917 Francis Poulenc, at the beginning of his career as a composer, was dismissive when Ravel praised Saint-Saëns as a genius.[104] By this time, various strands of new music were emerging with which Saint-Saëns had little in common. His classical instincts for form put him at odds with what seemed to him the shapelessness and structure of the musical impressionists, led by Debussy. Nor did the theories of Arnold Schönberg's dodecaphony commend themselves to Saint-Saëns:

There is no longer any question of adding to the old rules new principles which are the natural expression of time and experience, but simply of casting aside all rules and every restraint. "Everyone ought to make his own rules. Music is free and unlimited in its liberty of expression. There are no perfect chords, dissonant chords or false chords. All aggregations of notes are legitimate." That is called, and they believe it, the development of taste.[105]

Holding such conservative views, Saint-Saëns was out of sympathy – and out of fashion – with the Parisian musical scene of the early 20th century, fascinated as it was with novelty.[106] It is often said that he walked out, scandalised, from the premiere of Vaslav Nijinsky and Igor Stravinsky's ballet The Rite of Spring in 1913.[107] In fact, according to Stravinsky, Saint-Saëns was not present on that occasion, but at the first concert performance of the piece the following year he expressed the firm view that Stravinsky was insane.[108]

When a group of French musicians led by Saint-Saëns tried to organise a boycott of German music during the First World War, Fauré and Messager dissociated themselves from the idea, though the disagreement did not affect their friendship with their old teacher. They were privately concerned that their friend was in danger of looking foolish with his excess of patriotism,[109] and his growing tendency to denounce in public the works of rising young composers, as in his condemnation of Debussy's En blanc et noir (1915): "We must at all costs bar the door of the Institut against a man capable of such atrocities; they should be put next to the cubist pictures."[110] His determination to block Debussy's candidacy for election to the Institut was successful, and caused bitter resentment from the younger composer's supporters. Saint-Saëns's response to the neoclassicism of Les Six was equally uncompromising: of Darius Milhaud's polytonal symphonic suite Protée (1919) he commented, "fortunately, there are still lunatic asylums in France".[111]

Saint-Saëns gave what he intended to be his farewell concert as a pianist in Paris in 1913, but his retirement was soon in abeyance as a result of the war, during which he gave many performances in France and elsewhere, raising money for war charities.[99] These activities took him across the Atlantic, despite the danger from German warships.[112]

In November 1921, Saint-Saëns gave a recital at the Institut for a large invited audience; it was remarked that his playing was as vivid and precise as ever, and that his personal bearing was admirable for a man of eighty-six.[113] He left Paris a month later for Algiers, with the intention of wintering there, as he had long been accustomed to do. While there, he died without warning of a heart attack on 16 December 1921. His body was taken back to Paris, and after a state funeral at the Madeleine he was buried at the cimetière du Montparnasse.[114] Heavily veiled, in an inconspicuous place among the mourners from France's political and artistic élite, was his widow, Marie-Laure, whom he had last seen in 1881.[114]

Music

In the early years of the 20th century, the anonymous author of the article on Saint-Saëns in Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians wrote:

Saint-Saëns is a consummate master of composition, and no one possesses a more profound knowledge than he does of the secrets and resources of the art; but the creative faculty does not keep pace with the technical skill of the workman. His incomparable talent for orchestration enables him to give relief to ideas which would otherwise be crude and mediocre in themselves ... his works are on the one hand not frivolous enough to become popular in the widest sense, nor on the other do they take hold of the public by that sincerity and warmth of feeling which is so convincing.[115]

Although a keen modernist in his youth, Saint-Saëns was always deeply aware of the great masters of the past. In a profile of him written to mark his eightieth birthday, the critic D C Parker wrote, "That Saint-Saëns knows Rameau ... Bach and Handel, Haydn and Mozart, must be manifest to all who are familiar with his writings. His love for the classical giants and his sympathy with them form, so to speak, the foundation of his art."[116]

Less attracted than some of his French contemporaries to the continuous stream of music popularised by Wagner, Saint-Saëns often favoured self-contained melodies. Though they are frequently, in Ratner's phrase, "supple and pliable", more often than not they are constructed in three- or four-bar sections, and the "phrase pattern AABB is characteristic".[117] An occasional tendency to neoclassicism, influenced by his study of French baroque music, is in contrast with the colourful orchestral music more widely identified with him. Grove observes that he makes his effects more by characterful harmony and rhythms than by extravagant scoring. In both of those areas of his craft he was normally content with the familiar. Rhythmically, he inclined to standard double, triple or compound metres (although Grove points to a 5/4 passage in the Piano Trio and another in 7/4 in the Polonaise for two pianos). From his time at the Conservatoire he was a master of counterpoint; contrapuntal passages crop up, seemingly naturally, in many of his works.[117]

Orchestral works

The authors of the 1955 The Record Guide, Edward Sackville-West and Desmond Shawe-Taylor write that Saint-Saëns's brilliant musicianship was "instrumental in drawing the attention of French musicians to the fact that that there are other forms of music besides opera."[118] In the 2001 edition of Grove's Dictionary, Ratner and Daniel Fallon, analysing Saint-Saëns's orchestral music rate the unnumbered Symphony in A (c.1850) as the most ambitious of the composer's juvenilia. Of the works of his maturity, the First Symphony (1853) is a serious and large-scale work, in which the influence of Schumann is detectable. The "Urbs Roma" Symphony (1856) in some ways represents a backward step, being less deftly orchestrated, and "thick and heavy" in its effect.[117] Ratner and Fallon praise the Second Symphony (1859) as a fine example of orchestral economy and structural cohesion, with passages that show the composer's mastery of fugal writing. The best known of the symphonies is the Third (1886) which, unusually, has prominent parts for piano and organ. It opens in C minor and ends in C major with a stately chorale tune. The four movements are clearly divided into two pairs, a practice Saint-Saëns used elsewhere, notably in the Fourth Piano Concerto (1875) and the First Violin Sonata (1885).[117] The work is dedicated to the memory of Liszt, and uses a recurring motif treated in a Lisztian style of thematic transformation.[118]

Saint-Saëns's four symphonic poems follow the model of those by Liszt, though, in Sackville-West's and Shawe-Taylor's view, without the "vulgar blatancy" to which the earlier composer was prone.[119] The most popular of the four is Danse macabre (1874) depicting skeletons dancing at midnight. Saint-Saëns generally achieved his orchestral effects by deft harmonisation rather than exotic instrumentation,[117] but in this piece he featured the xylophone prominently, representing the rattling bones of the dancers.[120] Le Rouet d'Omphale (1871) was composed soon after the horrors of the Commune, but its lightness and delicate orchestration give no hint of recent tragedies.[121] Rees rates Phaëton (1873) as the finest of the symphonic poems, belying the composer's professed indifference to melody,[n 15] and inspired in its depiction of the mythical hero and his fate.[121] A critic at the time of the premiere took a different view, hearing in the piece "the noise of a hack coming down from Montmartre" rather than the galloping fiery horses of Greek legend that inspired the piece.[123] The last of the four symphonic poems, La jeunesse d'Hercule ("Hercules's Youth", 1877) was the most ambitious of the four, which, Harding suggests, is why it is the least successful.[124] In the judgment of the critic Roger Nichols these orchestral works, which combine striking melodies, strength of construction and memorable orchestration "set new standards for French music and were an inspiration to such young composers as Ravel".[111]

Saint-Saëns wrote a one-act ballet, Javot (1896), the score for the film L'assassinat du duc de Guise (1908),[n 16] and incidental music to a dozen plays between 1850 and 1916. Three of these scores were for revivals of classics by Molière and Racine, for which Saint-Saëns's deep knowledge of French baroque scores was reflected in his scores, in which he incorporated music by Lully and Charpentier.[27][126]

Concertante works

Saint-Saëns was the first major French composer to write piano concertos. His First, in D (1858), in conventional three-movement form, is not well known, but the Second, in G minor (1868) is one of his most popular works. The composer experimented with form in this piece, replacing the customary sonata form first movement with a more discursive structure, opening with a solemn cadenza. The scherzo second movement and presto finale are in such contrast with the opening that the pianist Zygmunt Stojowski commented that the work "begins like Bach and ends like Offenbach".[127] The Third Piano Concerto, in E♭ (1869) has another high-spirited finale, but the earlier movements are more classical, the texture clear, with graceful melodic lines.[16] The Fourth, in C minor (1875) is probably the composer's best-known piano concerto after the Second. It is in two movements, each comprising two identifiable sub-sections, and maintains a thematic unity not found in the composer's other piano concertos. According to some sources it was this piece that so impressed Gounod that he dubbed Saint-Saëns "the Beethoven of France" (other sources base that distinction on the Third Symphony).[128] The Fifth and last piano concerto, in F major, was written in 1896, more than twenty years after its predecessor. The work is known as the "Egyptian" concerto; it was written while the composer was wintering in Luxor, and incorporates a tune he heard Nile boatmen singing.[129]

The First Cello Concerto, in A minor (1872) is a serious although animated work, in a single continuous movement with an unusually turbulent first section. It is among the most popular concertos in the cello repertory, much favoured by Pablo Casals and later players.[130] The Second, in D minor (1902), like the Fourth Piano Concerto, consists of two movements each subdivided into two distinct sections. It is more purely virtuosic than its predecessor: Saint-Saëns commented to Fauré that it would never be as popular as the First because it was too difficult. There are three violin concertos; the first to be composed dates from 1858 but was not published until 1879, as the composer's Second, in C major.[131] The First, in A, was also completed in 1858. It is a short work, its single 314-bar movement lasting less than a quarter of an hour.[132] The Second, in conventional three-movement concerto form, is twice as long as the First, and is the least popular of the three: the thematic catalogue of the composer's works lists only three performances in his lifetime.[133] The Third, in B minor, written for Pablo de Sarasate, is technically challenging for the soloist, although the virtuoso passages are balanced by intervals of pastoral serenity.[134] It is by some margin the most popular of the three violin concertos, but Saint-Saëns's best-known concertante work for violin and orchestra is probably the Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso, in A minor, Op. 28, a single-movement piece, also written for Sarasate, dating from 1863. It changes from a wistful and tense opening to a swaggering main theme, described as faintly sinister by the critic Gerald Larner, who goes on, "After a multi-stopped cadenza ... the solo violin makes a breathless sprint through the coda to the happy ending in A major".[135]

Operas

Discounting his collaboration with Dukas in the completion of Guiraud's unfinished Frédégonde, Saint-Saëns wrote twelve operas, two of which are opéras comiques. During the composer's lifetime his Henry VIII became a repertory piece; since his death only Samson et Dalila has been regularly staged, although according to Schonberg, Ascanio (1890) is considered by experts to be a much finer work.[16][61] The critic Ronald Crichton writes that for all his experience and musical skill, Saint-Saëns "lacked the 'nose' of the theatre animal granted, for example, to Massenet who in other forms of music was his inferior".[61] In a 2005 study, the musical scholar Steven Huebner contrasts the two composers: "Saint-Saëns obviously had no time for Massenet's histrionics".[136] Saint-Saëns's biographer James Harding comments that it is regrettable that the composer did not attempt more works of a light-hearted nature, on the lines of La princesse jaune, which Harding describes as like Sullivan "with a light French touch".[137][n 17]

Although most of Saint-Saëns's operas have remained neglected, Crichton rates them as important in the history of French opera, as "a bridge between Meyerbeer and the serious French operas of the early 1890s".[138] In his view, the operatic scores of Saint-Saëns have, in general, the strengths and weaknesses of the rest of his music – "lucid Mozartian transparency, greater care for form than for content ... There is a certain emotional dryness; invention is sometimes thin, but the workmanship is impeccable."[61] Stylistically, Saint-Saëns drew on a range of models. From Meyerbeer he drew the effective use of the chorus in the action of a piece;[139] for Henry VIII he included Tudor music he had researched in London;[140] in La princesse jaune he used an oriental pentatonic scale;[117] from Wagner he derived the use of leitmotifs, which, like Massenet, he used sparingly.[141] Huebner observes that Saint-Saëns was more conventional than Massenet so far as through composition is concerned, more often favouring discrete arias and ensembles, with less variety of tempo within individual numbers.[142] In a survey of recorded opera Alan Blyth writes that Saint-Saëns "certainly learned much from Handel, Gluck, Berlioz, the Verdi of Aida, and Wagner, but from these excellent models he forged his own style."[143]

Other vocal music

From the age of six and for the rest of his life Saint-Saëns composed mélodies, writing more than 140.[144] He regarded his songs as thoroughly and typically French, denying any influence from Schubert or other German composers of Lieder.[145] Unlike his protégé Fauré, or his rival Massenet, he was not drawn to the song cycle, writing only two during his long career – Mélodies persanes ("Persian Songs", 1870) and Le Cendre rouge ("The Red Ash Tree", 1914, dedicated to Fauré). The poet whose works he set most often was Victor Hugo; others included Alphonse de Lamartine, Pierre Corneille, Amable Tastu, and, in eight songs, Saint-Saëns himself: among his many non-musical talents he was an amateur poet. He was highly sensitive to word setting, and told the young composer Lili Boulanger that to write songs effectively musical talent was not enough: "you must study the French language in depth; it is indispensable."[146] Most of the mélodies are written for piano accompaniment, but a few, including "Le lever du soleil sur le Nil" ("Sunrise over the Nile", 1898) and "Hymne à la paix" ("Hymn to Peace", 1919), are for voice and orchestra.[27] His settings, and chosen verses, are generally traditional in form, contrasting with the free verse and less structured forms of a later generation of French composers, including Debussy.[147]

Saint-Saëns composed more than sixty sacred vocal works, ranging from motets to masses and oratorios. Among the larger-scale compositions are the Requiem (1878) and the oratorios Le déluge (1875) and The Promised Land (1913) with an English text by Herman Klein.[27] He was proud of his connection with British choirs, commenting, "One likes to be appreciated in the home, par excellence, of oratorio."[36] He wrote a smaller number of secular choral works, some for unaccompanied choir, some with piano accompaniment and some with full orchestra.[27] In his choral works, Saint-Saëns drew heavily on tradition, feeling that his models should be Handel, Mendelssohn and other earlier masters of the genre. In Klein's view, this approach was old-fashioned, and the familiarity of Saint-Saëns's treatment of the oratorio form impeded his success in it.[36]

Solo keyboard

Nichols comments that, although as a famous pianist Saint-Saëns wrote for the piano throughout his life, "this part of his oeuvre has made curiously little mark".[111] Nichols excepts the Étude en forme de valse (1912), which he observes still attracts pianists eager to display their left-hand technique.[111] Although Saint-Saëns was dubbed "the French Beethoven", and his Variations on a Theme of Beethoven in E♭ (1874) is his most extended work for unaccompanied piano, he did not emulate his predecessor in composing piano sonatas. He is not known even to have contemplated writing one.[148] There are sets of bagatelles (1855), études (two sets – 1899 and 1912) and fugues (1920), but in general Saint-Saëns's works for the piano are single short pieces. In addition to established forms such as the song without words (1871) and the mazurka (1862, 1871 and 1882) popularised by Mendelssohn and Chopin, respectively, he wrote descriptive pieces such as "Souvenir d'Italie" (1887), "Les cloches du soir" ("Evening bells", 1889) and "Souvenir d'Ismaïlia" (1895).[27][149]

Unlike his pupil, Fauré, whose long career as a reluctant organist left no legacy of works for the instrument, Saint-Saëns published a modest number of pieces for organ solo.[150] Some of them were written for use in church services – "Offertoire" (1853), "Bénédiction nuptiale" (1859), "Communion" (1859) and others. After he left the Madeleine in 1877 Saint-Saëns wrote ten more pieces for organ, mostly for concert use, including two sets of preludes and fugues (1894 and 1898). Some of the earlier works were written to be played on either the harmonium or the organ, and a few were primarily intended for the former.[27]

Chamber

Saint-Saëns wrote more than forty chamber works between the 1840s and his last years. One of the first of his major works in the genre was the Piano Quintet (1855). It is a straightforward, confident piece, in a conventional structure with lively outer movements and a central movement containing two slow themes, one chorale-like and the other cantabile.[151] The Septet (1880), for the unusual combination of trumpet, two violins, viola, cello, double bass and piano, is a neoclassical work that draws on 17th-century French dance forms. At the time of its composition Saint-Saëns was preparing new editions of the works of baroque composers including Rameau and Lully.[117]

Sabina Teller Ratner, 2005[151]

In Ratner's view, the most important of Saint-Saëns's chamber works are the sonatas: two for violin, two for cello, and one each for oboe, clarinet and bassoon, all seven with piano accompaniment.[151] The First Violin Sonata dates from 1885, and is rated by Grove's Dictionary as one of the composer's best and most characteristic compositions. The Second (1896) signals a stylistic change in Saint-Saëns's work, with a lighter, clearer sound for the piano, characteristic of his music from then onwards.[117] The First Cello Sonata (1872) was written after the death of the composer's great-aunt, who had taught him to play the piano more than thirty years earlier. It is a serious work, in which the main melodic material is sustained by the cello over a virtuoso piano accompaniment. Fauré called it the only cello sonata from any country to be of any importance.[152] The Second (1905) is in four movements, and has the unusual feature of a theme and variations as its scherzo.[101]

The woodwind sonatas are among the composer's last works. Ratner writes of them, "The spare, evocative, classical lines, haunting melodies, and superb formal structures underline these beacons of the neoclassical movement."[151] Gallois comments that the Oboe Sonata begins like a conventional classical sonata, with an andantino theme; the central section has rich and colourful harmonies, and the molto allegro finale is full of delicacy, humour and charm with a form of tarantella. For Gallois the Clarinet Sonata is the most important of the three: he calls it "a masterpiece full of impishness, elegance and discreet lyricism" amounting to "a summary of the rest".[153] The work contrasts a "doleful threnody" in the slow movement with the finale, which "pirouettes in 4/4 time", in a style reminiscent of the 18th century. The same commentator calls the Bassoon Sonata "a model of transparency, vitality and lightness", containing humorous touches but also moments of peaceful contemplation.[154]

The composer's most famous work, The Carnival of the Animals (1887), although far from a typical chamber piece, is written for eleven players, and is considered by Grove's Dictionary to be part of Saint-Saëns's chamber output. Grove rates it as "his most brilliant comic work, parodying Offenbach, Berlioz, Mendelssohn, Rossini, his own Danse macabre and several popular tunes".[117] He forbade performances of it during his lifetime, concerned that its frivolity would damage his reputation as a serious composer.[6]

Recordings

Saint-Saëns was a pioneer in recorded music. In June 1904 The Gramophone Company of London sent its producer Fred Gaisberg to Paris to record Saint-Saëns as accompanist to the mezzo-soprano Meyriane Héglon in arias from Ascanio and Samson et Dalila, and as soloist in his own piano music, including an arrangement of sections of the Second Piano Concerto (without orchestra).[155] Saint-Saëns made more recordings for the company in 1919.[155]

In the early days of the LP record, Saint-Saëns's works were patchily represented on disc. The Record Guide (1955) lists one recording apiece of the Third Symphony, Second Piano Concerto and First Cello Concerto, alongside several versions of Danse Macabre, The Carnival of the Animals, the Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso and other short orchestral works.[156] In the latter part of the 20th century and the early 21st, many more of the composer's works were released on LP and later CD and DVD. The 2008 Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music contains ten pages of listings of Saint-Saëns works, including all the concertos, symphonies, symphonic poems, sonatas and quartets. Also listed are an early Mass, collections of organ music, and choral songs.[157] A recording of twenty-seven of Saint-Saëns's mélodies was released in 1997.[158]

With the exception of Samson et Dalila the operas have been sparsely represented on disc. A recording of Henry VIII was issued on CD and DVD in 1992.[159] Hélène was released on CD in 2008.[160] There are several recordings of Samson et Dalilah, under conductors including Sir Colin Davis, Georges Prêtre, Daniel Barenboim and Myung-Whun Chung.[161]

Honours and reputation

Saint-Saëns was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1867 and promoted to Officier in 1884, and Grand Croix in 1913. Foreign honours included the British Royal Victorian Order (CVO) in 1902, and honorary doctorates from the universities of Cambridge (1893) and Oxford (1907).[162][163]

In its obituary notice, The Times commented:

The death of M. Saint-Saëns not only deprives France of one of her most distinguished composers; it removes from the world the last representative of the great movements in music which were typical of the 19th century. He had maintained so vigorous a vitality and kept in such close touch with present-day activities that, though it had become customary to speak of him as the doyen of French composers, it was easy to forget the place he actually took in musical chronology. He was only two years younger than Brahms, was five years older than Tchaikovsky, six years older than Dvořák, and seven years older than Sullivan. He held a position in his own country's music certain aspects of which may be fitly compared with each of those masters in their own spheres.[162]

In a short poem, "Mea culpa", published in 1890 Saint-Saëns accused himself of lack of decadence, and commented approvingly on the excessive enthusiasms of youth, lamenting that such things were not for him.[n 18] An English commentator quoted the poem in 1910, observing, "His sympathies are with the young in their desire to push forward, because he has not forgotten his own youth when he championed the progressive ideals of the day."[165] The composer sought a balance between innovation and traditional form. The critic Henry Colles, wrote, a few days after the composer's death:

In his desire to maintain "the perfect equilibrium" we find the limitation of Saint-Saëns's appeal to the ordinary musical mind. Saint-Saëns rarely, if ever, takes any risks; he never, to use the slang of the moment, "goes off the deep end". All his greatest contemporaries did. Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and even Franck, were ready to sacrifice everything for the end each wanted to reach, to drown in the attempt to get there if necessary. Saint-Saëns, in preserving his equilibrium, allows his hearers to preserve theirs.[166]

Grove concludes its article on Saint-Saëns with the observation that although his works are remarkably consistent, "it cannot be said that he evolved a distinctive musical style. Rather, he defended the French tradition that threatened to be engulfed by Wagnerian influences and created the environment that nourished his successors".[117]

Since the composer's death writers sympathetic to his music have expressed regret that he is known by the musical public for only a handful of his scores such as The Carnival of the Animals, the Second Piano Concerto, the Third Violin Concerto, the Organ Symphony, Samson et Dalila, Danse macabre and the Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso. Among his large output, Nicholas singles out the Requiem, the Christmas Oratorio, the ballet Javotte, the Piano Quartet, the Septet for trumpet, piano and strings, and the First Violin Sonata as neglected masterpieces.[47] In 2004, the cellist Steven Isserlis said, "Saint-Saens is exactly the sort of composer who needs a festival to himself ... there are Masses, all of which are interesting. I've played all his cello music and there isn't one bad piece. His works are rewarding in every way. And he's an endlessly fascinating figure."[6]

See also

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- UK: /ˈsæ̃sɒ̃(s)/,[1] US: /sæ̃ˈsɒ̃(s)/.[2][3] Although French-speaking musicians and intellectuals often still use the traditional pronunciation without S at the end ([sɛ̃ sɑ̃]), the pronunciation with S is now very common in French, even among radio announcers. Saint-Saëns himself wanted his name to be pronounced like that of the town Saint-Saëns, which was pronounced without S at the end until about 1940–1950 in accordance with the spelling without S that was in use until about 1840–1860, as explained by Claude Fournier in his history of the town.[4] The diaeresis on the e dates from a time when the e was not silent, but the diaeresis no longer affects the pronunciation of the name(s) because the e is silent, as in the name Madame de Staël, for example.

- During the Dreyfus affair when anti-Semitism was rife among opponents of Alfred Dreyfus, it was rumoured that Saint-Saëns, who had contributed money for Dreyfus's defence, was really surnamed "Kahn".[6][7] Indeed, some early 20th-century music historians such as Gdal Saleski reported that Saint-Saëns was of partial Jewish origin.[8] In fact Saint-Saëns had no Jewish ancestry, which did not stop the Nazis from banning his music during their regime in Germany.[9]

- In a 2012 symposium on Saint-Saëns, Léo Houziaux contributed a study of the composer's contributions to astronomy, including three papers he wrote between 1889 and 1913 for French journals.[18] Houziaux concludes that Saint-Saëns's contributions helped to popularise the science of astronomy in France.[19]

- The Conservatoire remained a bastion of musical conservatism until 1905, when Saint-Saëns's former pupil Gabriel Fauré became director and radically liberalised the curriculum.[21]

- Saint-Saëns had been composing since the age of three; his mother preserved his early works, and in adult life he was surprised to find them technically competent though of no great musical interest.[25] The earliest surviving piece, dated March 1839, is in the collection of the Paris Conservatoire.[13]

- The harmonium having gone out of general use, Henri Büsser transcribed the work for organ in 1935.[29]

- Other writers recount and date the saying differently. Saint-Saëns recalled in old age that the comment was made about him when he was eighteen, by Gounod rather than Berlioz.[43] Jules Massenet, according to his own memoirs, was the subject of the joke in 1863, when Auber said to Berlioz, "He'll go far, the young rascal, when he's had less experience."[44]

- In practice the decision was left to Berlioz and Verdi, as Rossini never turned up for meetings, Auber slept through them, and Gounod resigned.[50]

- Despite the public perception at the time and subsequently, the new Société Nationale de Musique was not itself anti-German. Saint-Saëns and his colleagues believed in freedom of artistic expression for artists of all countries, and despite France's humiliation by Prussia many French artists maintained a strong respect for German culture.[54]

- In a 2012 study of the composer's private life, Mitchell Morris mentions but classes as apocryphal a story attributing to Saint-Saëns the remark, "Je ne suis pas homosexuel. Je suis pédéraste".[76] According to Benjamin Ivry in a 2000 biography of Maurice Ravel, Saint-Saëns "was plagued by blackmailing letters from North African men he paid, apparently too little, for sex"; Ivry cites no authority for the statement.[77] Stephen Studd (1999) and Kenneth Ring (2002) conclude that apart from his marriage, Saint-Saëns's relationships and inclinations were platonic.[78] The composer himself was indifferent to rumours about him: "If it is said that I have a bad character, I assure you that it is all the same to me. Take me as I am."[79]

- Although Saint-Saëns maintained an amicable relationship with Massenet, he privately disliked and mistrusted him.[63] Nonetheless each had the highest respect for the other's music; Massenet used Saint-Saëns's works as models for his composition students, and Saint-Saëns called Massenet "one of the most brilliant diamonds in our musical crown".[64] Saint-Saëns was fonder of Madame Massenet, to whom he dedicated his Concert Paraphrase of "Le mort de Thaïs" from her husband's 1893 opera.[65]

- Saint-Saëns was a Deist rather than a Christian; he disapproved of atheism: "The proofs of God's existence are irrefutable [although] they lie without the domain of science and belong to that of metaphysics."[69]

- Studying Handel manuscripts in London, Saint-Saëns was disconcerted to find a composer who worked even more quickly than he did.[83]

- In 1909 d'Indy's inflexibility led a new generation of composers, led by Fauré's pupils Ravel and Charles Koechlin, to break away and found a new group, Société Musicale Indépendant, whose ideals were closer to the original vision of Saint-Saëns and his colleagues in 1870.[85]

- Saint-Saëns wrote in his book Musical Memories, "He who does not get absolute pleasure from a simple series of well-constructed chords, beautiful only in their arrangement, is not really fond of music."[122]

- This music is sometimes cited as the first score composed for a film, but there were earlier examples including one by Herman Finck (1904).[125]

- Saint-Saëns was friendly with Sullivan, and liked his music, making a point of seeing the latest Savoy opera when in London.[137]

- "Mea culpa! Je m'accuse de n'être point décadent."[164]

References

- {{Cite Oxford Dictionaries|Saint-Saëns, Camille|accessdate=10 August 2019}}

- "Saint-Saëns". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- "Saint-Saëns". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Doit-on prononcer le "s" final de Saint-Saëns ? Archived 16 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- Ratner, Sabina Teller. "Saint-Saëns, Camille: Life", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 February 2015 (subscription required)

- Duchen, Jessica. " The composer who disappeared (twice)", The Independent, 19 April 2004

- Prod'homme, p. 470

- Wingard, Eileen. Saint-Saens concert brought together unusual combination of two keyboardists Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, San Diego Jewish World, 14 February 2011

- Kater, p. 85

- Rees, p. 22

- Saint-Saëns, p. 3

- Studd, p. 6; and Rees, p. 25

- Schonberg, p. 42

- Gallois, p. 19

- Saint-Saëns, pp. 8–9

- Schonberg, Harold C. "It All Came Too Easily For Camille Saint-Saëns", The New York Times, 12 January 1969, p. D17

- Rees, p. 40

- Houziaux, pp. 12–25

- Houziaux, p. 17

- Rees, p. 53

- Nectoux, p. 269

- Rees, p. 41

- Rees, p. 48

- Macdonald, Hugh. "Benoist, François", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 12 February 2015 (subscription required)

- Saint-Saëns, p. 7

- Macdonald, Hugh. "Halévy, Fromental", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 11 February 2015 (subscription required)

- Fallon, Daniel. "Camille Saint-Saëns: List of works", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 13 February 2015 (subscription required)

- Studd, p. 29

- Ratner (2002), p. 94

- Smith, p. 10

- Rees, p. 65

- Rees, p. 67

- Studd, p. 30

- Rees, p. 87; and Harding, p. 62

- Nectoux, p. 39; and Parker, p. 574

- Klein, p. 91

- Jones (1989), p. 16

- Fauré in 1922, quoted in Nectoux, pp. 1–2

- Ratner (1999), p. 120

- Ratner (1999), p. 136

- Berlioz, p. 430

- Gallois, p. 96

- Bellaigue, p. 59; and Rees, p. 395

- Massenet, pp. 27–28

- Rees, p. 122

- Harding, p. 61: and Studd, p. 201

- Nicholas, Jeremy. "Camille Saint-Saëns" Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, BBC Music Magazine. Retrieved 15 February 2015

- Ratner (1999), p. 119

- "Paris Universal Exhibition", The Morning Post, 24 July 1867, p. 6

- Harding. p. 90

- Ratner (1999), p. 133

- Tombs, p. 124

- Studd, p. 84

- Strasser, p. 251

- Jones (2006), p. 55

- Simeone, p. 122

- Macdonald, Hugh. "Princesse jaune, La", The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 16 February 2015 (subscription required)

- Rees, pp. 189–190

- Harding, p. 148

- Studd, p. 121

- Crichton, pp. 351–353

- Macdonald, Hugh. "Massenet, Jules", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 15 February 2015 (subscription required)

- Branger, pp. 33–38

- Saint-Saëns, pp. 212 and 218

- Ratner (2002), p. 479

- Rees, pp. 137–138 and 155

- Macdonald, Hugh. "Timbre d'argent, Le", The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 16 February 2015 (subscription required)

- Smith, p. 108

- Prod'homme, p. 480

- Ring, p. 9; and Smith, p. 107

- Smith, pp. 106–108

- Leteuré, p. 135

- Smith, p. 119

- Smith, pp. 120–121

- Rees, pp. 198–201

- Morris, p. 2

- Ivry, p. 18

- Studd, pp. 252–254; and Ring, pp. 68–70

- Studd, p. 253

- Duchen, p. 69

- Nectoux and Jones (1989), p. 68

- Macdonald, Hugh. "Saint-Saëns, Camille", The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 18 February 2015 (subscription required)

- Rees, p. 242

- "Royal Opera, Covent-Garden", The Era, 16 July 1898, p. 11

- Jones (1989), p. 133

- Harding, p. 116

- "Philharmonic Society", The Times, 22 May 1886, p. 5; and "Music – Philharmonic Society", The Daily News, 27 May 1886, p. 6

- Deruchie, pp. 19–20

- Leteuré, p. 134

- Studd, pp. 172–173

- Rees, p. 286

- Jones (1989), p. 69

- "New Opera by Saint-Saëns", The Times, 25 May 1893, p. 5

- Studd, pp. 203–204

- "M. Saint-Saëns", The Times, 5 June 1896, p. 4

- "Cambridge University Musical Society", The Times, 13 June 1893, p. 10

- Harding, p. 185

- "Gloucester Music Festival", The Times, 12 September 1913, p. 4

- Prod'homme, p. 484

- Rees, pp. 370–371 and 381

- Rees, p. 381

- Gallois, p. 350

- Nectoux, p. 238

- Nichols. p. 117

- Saint-Saëns, p. 95

- Morrison, p. 64

- Glass, Philip. "The Classical Musician: Igor Stravinsky" Archived 10 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Time, 8 June 1998; Atamian, Christopher. "Rite of Spring as Rite of Passage" Archived 7 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 11 November 2007; and "Love and Ruin: Saint-Saens' 'Samson and Dalila'" Archived 17 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Washington National Opera, 20 June 2008

- Kelly, p. 283; and Canarina, p. 47

- Jones (1989), pp. 162–165

- Nectoux, p. 108

- Nichols, Roger. "Saint-Saëns, (Charles) Camille", The Oxford Companion to Music, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 21 February 2015 (subscription required)

- Rees, p. 430

- Prod'homme, p. 469

- Studd, p. 288

- Fuller Maitland, p. 208

- Parker, p. 563

- Fallon, Daniel, and Sabina Teller Ratner. "Saint-Saëns, Camille: Works", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 18 February 2015 (subscription required)

- Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 641

- Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, pp. 642–643

- Rees, p. 182

- Rees, p. 177

- Saint-Saëns, p. 109

- Jones (2006), p. 78

- Harding, p. 123

- Wierzbicki, p. 41

- Rees, p. 299

- Herter, p. 75

- Anderson (1989), p. 3; and Deruchie, p. 19

- Rees, p. 326

- Ratner (2002), p. 364

- Ratner (2002), p. 340

- Ratner (2002), p. 343

- Ratner (2002), p. 339

- Anderson (2009), pp. 2–3

- Larner, pp. 3–4

- Huebner, p. 226

- Harding, p. 119

- Crichton, p. 353

- Huebner, p. 215

- Huebner, p. 218

- Huebner, p. 222

- Huebner, pp. 223–224

- Blyth, p. 94

- Fauser, p. 210

- Fauser, p. 217

- Fauser, p. 211

- Fauser, p. 228

- Rees, p. 198

- Brown, Maurice J E, and Kenneth L Hamilton. "Song without words", and Downes, Stephen. "Mazurka" Archived 17 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 20 February 2015 (subscription required)

- Nectoux, pp. 525–558

- Ratner (2005), p. 6

- Rees, p. 167

- Gallois, p. 368

- Gallois, pp. 368–369

- Introduction Archived 6 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine and Track Listing Archived 6 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, "Legendary piano recordings: the complete Grieg, Saint-Saëns, Pugno, and Diémer and other G & T rarities", Ward Marston. Retrieved 24 February 2014

- Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, pp. 642–644

- March, pp. 1122–1131

- "Songs – Saint Saëns" Archived 6 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, WorldCat. Retrieved 24 February 2015

- "Henry VIII" Archived 6 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, WorldCat. Retrieved 24 February 2015

- "Hélène" Archived 6 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, WorldCat. Retrieved 24 February 2015

- March, p. 1131

- "M. Saint-Saëns", The Times, 19 December 1921, p. 14

- "Saint-Saëns, Camille", Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2015 (subscription required)

- Gallois, p. 262

- "M. Saint-Saëns's Essays", The Times Literary Supplement, 23 June 1910, p. 223

- Colles, H. C. "Camille Saint-Saëns", The Times Literary Supplement, 22 December 1921, p. 853

Sources

- Anderson, Keith (1989). Notes to Naxos CD Saint-Saëns, Piano Concertos 2 and 4. Munich: Naxos. OCLC 27875994.

- Anderson, Keith (2009). Notes to Naxos CD Saint-Saëns, Violin Concertos. Munich: Naxos. OCLC 671720802.

- Bellaigue, Camille (1921). Souvenirs de musique et de musiciens (in French). Paris: Nouvelle Librairie Nationale. OCLC 15309469.

- Berlioz, Hector (1995). Hugh Macdonald (ed.). Berlioz, Selected Letters. Roger Nichols (trans). London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-14881-3.

- Blyth, Alan (1992). Opera on CD. London: Kyle Cathie. ISBN 978-1-85626-103-6.

- Branger, Jean-Christophe (2012). "Rivals and Friends: Saint-Saëns, Massenet and Thaïs". In Jann Passler (ed.). Saint-Saëns and his World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15555-5.

- Canarina, John (2003). Pierre Monteux, Maître. Pompton Plains, New Jersey: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-1-57467-082-0.

- Crichton, Ronald (1997) [1993]. "Camille Saint-Saëns". In Amanda Holden (ed.). The Penguin Opera Guide. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-051385-1.

- Deruchie, Andrew (2013). The French Symphony at the Fin de siècle. Rochester, NY and Woodbridge, Suffolk: University of Rochester Press, and Boydell and Brewer. ISBN 978-1-58046-382-9.

- Duchen, Jessica (2000). Gabriel Fauré. London: Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-3932-5.

- Duchesneau, Michel (2012). "The Fox in the Henhouse: Saint-Saëns at the SMI". In Jann Passler (ed.). Saint-Saëns and his World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15555-5.

- Fauser, Annegret (2012). "What's in a song? Saint-Saëns's Mélodies". In Jann Passler (ed.). Saint-Saëns and his World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15555-5.

- Fuller Maitland, J A (1908). Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Volume IV (second ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 252807560.

- Gallois, Jean (2004). Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns (in French). Sprimont, Belgium: Éditions Mardaga. ISBN 978-2-87009-851-6.

- Harding, James (1965). Saint-Saëns and his Circle. London: Chapman and Hall. OCLC 60222627.

- Herter, Joseph (2007). Zygmunt Stojowski. Los Angeles: Figueroa Press. ISBN 978-1-932800-26-5.

- Hervey, Arthur (1921): Saint-Saëns (London: John Lane)

- Houziaux, Léo (2012). "Inspired by the Skies". In Jann Passler (ed.). Saint-Saëns and his World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15555-5.

- Huebner, Steven (2005). French Opera at the Fin de siècle. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518954-4.

- Ivry, Benjamin (2000). Maurice Ravel: A Life. New York: Welcome Rain. ISBN 978-1-56649-152-5.

- Jones, J Barrie (1989). Gabriel Fauré – A Life in Letters. London: B T Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-5468-0.

- Jones, Timothy (2006). "Nineteenth-Century Orchestral and Chamber Music". In Richard Langham Smith; Caroline Potter (eds.). French Music Since Berlioz. Aldershot and Burlington: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-0282-8.

- Kater, Michael H (1999). The Twisted Muse: Musicians and Their Music in the Third Reich. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513242-7.

- Kelly, Thomas Forrest (2000). First Nights: Five Musical Premieres. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07774-2.

- Klein, Herman (February 1922). "Saint-Saëns as I Knew Him". The Musical Times. 63 (948): 90–93. doi:10.2307/910966. ISSN 0027-4666. JSTOR 910966. (subscription required)

- Larner, Gerald (1990). Notes to Chandos CD Violin Favourites. Colchester: Chandos. OCLC 42524241.

- Leteuré, Stephane (2012). "Saint-Saëns: The Traveling Musician". In Jann Passler (ed.). Saint-Saëns and his World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15555-5.

- March, Ivan, ed. (2007). Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-141-03336-5.

- Massenet, Jules (1919) [1910]. My Recollections. H Villiers Barnett (trans). Boston: Small Maynard. OCLC 774419363.

- Morris, Mitchell (2012). "Saint-Saëns in (Semi-)Private". In Jann Passler (ed.). Saint-Saëns and his World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15555-5.

- Morrison, Simon (Summer 2004). "The Origins of Daphnis et Chloé (1912)". 19th-Century Music. 28: 50–76. doi:10.1525/ncm.2004.28.1.50. JSTOR 10.1525/ncm.2004.28.1.50. (subscription required)

- Nectoux, Jean-Michel (1991). Gabriel Fauré – A Musical Life. Roger Nichols (trans). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23524-2.

- Nectoux, Jean-Michel; J Barrie Jones (2004). The Correspondence of Camille Saint-Saëns and Gabriel Fauré: Sixty Years of Friendship. Aldershot and Burlington: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-3280-1.

- Nichols, Roger (1987). Ravel Remembered. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-14986-5.

- Parker, D C (October 1919). "Camille Saint-Saëns: A Critical Estimate". The Musical Quarterly. 5 (4): 561–577. doi:10.1093/mq/v.4.561. ISSN 0027-4631. JSTOR 738128.

- Prod'homme, Jacques-Gabriel (October 1922). "Camille Saint-Saëns" (PDF). The Musical Quarterly. 8: 469–486. doi:10.1093/mq/viii.4.469. ISSN 0027-4631. JSTOR 737853. (subscription required)

- Ratner, Sabina Teller (1999). "Camille Saint-Saëns: Fauré's mentor". In Tom Gordon (ed.). Regarding Fauré. Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach. ISBN 978-90-5700-549-7.

- Ratner, Sabina Teller (2002). Camille Saint-Saëns, 1835–1922: A Thematic Catalogue of his Complete Works, Volume 1: The Instrumental Works. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816320-6.

- Ratner, Sabina Teller (2005). Notes to Hyperion CD Saint-Saëns Chamber Music. London: Hyperion. OCLC 61134605.

- Rees, Brian (1999). Camille Saint-Saëns – A Life. London: Chatto and Windus. ISBN 978-1-85619-773-1.

- Ring, Kenneth (2002). Psychological Perspective on Camille Saint-Saëns. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-7108-5.

- Sackville-West, Edward; Desmond Shawe-Taylor (1955). The Record Guide. London: Collins. OCLC 500373060.

- Saint-Saëns, Camille (1919). Musical Memories. Edwin Gile Rich (trans). Boston: Small, Maynard. OCLC 385307.

- Schonberg, Harold C (1975). The Lives of the Great Composers. 2. London: Futura. ISBN 978-0-86007-723-7.

- Simeone, Nigel (2000). Paris – A Musical Gazetteer. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08053-7.

- Smith, Rollin (1992). Saint-Saëns and the Organ. Stuyvesant: Pendragon Press. ISBN 978-0-945193-14-2.

- Strasser, Michael (Spring 2001). "The Société Nationale and its Adversaries: The Musical Politics of L'Invasion germanique in the 1870s". 19th-Century Music. 24 (3): 225–251. doi:10.1525/ncm.2001.24.3.225. ISSN 0148-2076. JSTOR 10.1525/ncm.2001.24.3.225. (subscription required)

- Studd, Stephen (1999). Camille Saint-Saëns – A Critical Biography. London: Cygnus Arts. ISBN 978-0-8386-3842-2.

- Tombs, Robert (1999). The Paris Commune, 1871. London: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-30915-9.

- Wierzbicki, James (2009). Film Music: A History. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-85143-9.

Further reading

- Flynn, Timothy (2015). "The Classical Reverberations in the Music and Life of Camille Saint-Saëns". Music in Art: International Journal for Music Iconography. 40 (1–2): 255–264. ISSN 1522-7464.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Camille Saint-Saëns. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Camille Saint-Saëns |

- Camille Saint-Saëns at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Camille Saint-Saëns on IMDb

- Camille Saint-Saëns at AllMusic

- Works by Camille Saint-Saëns at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Camille Saint-Saëns at Internet Archive

- Search "Camille Saint-Saëns" on OBPS

- Works by Camille Saint-Saëns at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Saint-Saëns on film playing his Valse Mignonne (video plus audio) on YouTube

- Saint-Saëns playing his own Piano Concerto No. 2 (opening) on YouTube

- Saint-Saëns playing Rhapsodie d'Auvergne Op. 73 on YouTube

- Free scores by Saint-Saëns at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Camille Saint-Saëns in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- The Mutopia Project has compositions by Camille Saint-Saëns

- Camille Saint-Saëns' "Organ-Symphony": Symphony No. 3 in c minor, Op. 78, Spanish Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra (together with works of Debussy and Fauré)