Richardoestesia

Richardoestesia is a medium-sized (about 100 kilograms (220 lb)) genus of theropod dinosaur from the late Cretaceous Period of what is now North America. It currently contains two species, R. gilmorei and R. isosceles.

| Richardoestesia | |

|---|---|

| |

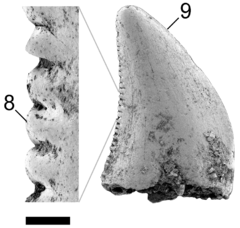

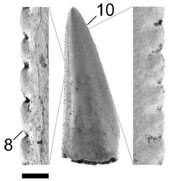

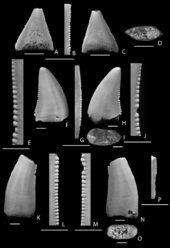

| Tooth of cf. R. gilmorei with close up of denticles | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Coelurosauria |

| Genus: | †Richardoestesia Currie, Rigby & Sloan, 1990 |

| Type species | |

| †Richardoestesia gilmorei Currie, Rigby & Sloan, 1990 | |

| Species | |

| |

Species

The holotype specimen of Richardoestesia gilmorei (NMC 343) consists of the pair of lower jaws found in the upper Judith River Group, dating from the Campanian age, about 75 million years ago. The jaws are slender and rather long, 193 millimeter, but the teeth are small and very finely serrated with five to six denticles per millimeter. The serration density is a distinctive trait of the species.

In 2001, Julia Sankey named a second species: Richardoestesia isosceles, based on a tooth, LSUMGS 489:6238, from the Texan Aguja Formation, which is of a longer and less recurved type.[1] The teeth of R. isosceles have also been identified as crocodyliform in shape, possibly belonging to a sebecosuchian.[2]

Research

The jaws were found in 1917 by Charles Hazelius Sternberg and sons in the Dinosaur Provincial Park in Alberta at the Little Sandhill Creek site. In 1924 Charles Whitney Gilmore named Chirostenotes pergracilis and referred the jaws to this species.[3] In the eighties it became clear that Chirostenotes was an oviraptosaur to which the long jaws could not have belonged. Therefore, in 1990 Phillip Currie, John Keith Rigby and Robert Evan Sloan named a separate species: Richardoestesia gilmorei.[4] The genus is named for Richard Estes, to honor his important work[5] on small vertebrates and especially theropod teeth of the Late Cretaceous. The naming authors actually intended to use the spelling Ricardoestesia, Ricardus being the normal latinisation of "Richard". However, except in one overlooked figure caption, the editors of the paper altered the spelling to include the 'h'. Ironically, in 1991 George Olshevsky in a species list also used the spelling Richardoestesia, and indicated Ricardoestesia to be the misspelling, unaware that the original authors actually intended the name to be spelled this way. As a result, under ICZN rules, he acted as "first revisor" choosing between the two spelling variants of the original publication and inadvertently made the misspelt name official. Subsequently, the original authors have adopted the spelling Richardoestesia. The specific name honors Gilmore.

Age range

Richardoestesia-like teeth have been found in many Late Cretaceous geological formations, including the Horseshoe Canyon Formation, the Scollard Formation, Hell Creek Formation, Ferris Formation, and the Lance Formation (dated to about 66 million years ago). Similar teeth have been referred to this genus from as early as the Barremian age (Cedar Mountain Formation, 125 million years ago).[6]

Because of the disparity in location and time of the many referred teeth, researchers have cast doubt on the idea that they all belong to the same genus or species, and the genus is best considered a form taxon. A comparative study of the teeth published in 2013 demonstrated that both R. gilmorei and R. isosceles were only definitively present in the Dinosaur Park Formation, dated to between 76.5 and 75 million years ago. R. isosceles was also present in the Aguja Formation, roughly the same age. All other referred teeth most likely belong to different species, which have not been named due to the lack of body fossils for comparison.[7]

Fossils of Richartoestesia have also been found in the Tremp Formation of northeastern Spain and possibly also the Lourinha Formation (Blasi 2 member) of Portugal, although this is unlikely since the Lourinha Formation dates to the Late Jurassic (152 Ma).[8]

References

- J.T. Sankey, 2001, "Late Campanian southern dinosaurs, Aguja Formation, Big Bend, Texas", Journal of Paleontology 75(1): 208-215

- Company, J.; Suberbiola, X.P.; Ruiz-Omenaca, J.I.; Buscalioni, A.D. (2005). "A new species of Doratodon (Crocodyliformes: Ziphosuchia) from the Late Cretaceous of Spain" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (2): 343–353. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0343:ANSODC]2.0.CO;2.

- Gilmore, C.W., 1924, "A new coelurid dinosaur from the Belly River Cretaceous of Alberta", Canada Department of Mines Geological Survey Bulletin (Geological Series) 38(43): 1-12

- Currie, P. J., K. J. Rigby, and R. E. Sloan. 1990. "Theropod teeth from the Judith River Formation of southern Alberta, Canada". Pp. 107–125. In P. J. Currie, and K. Carpenter, eds. Dinosaur Systematics: Perspectives and Approaches. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Estes, R., 1964, Fossil vertebrates from the Late Cretaceous Lance Formation, eastern Wyoming. University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 49: 1-180

- Kirkland, Lucas and Estep, (1998). "Cretaceous dinosaurs of the Colorado Plateau." in Lucas, Kirkland and Estep (eds.). Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 14, 79-89.

- Larson DW, Currie PJ (2013) Multivariate Analyses of Small Theropod Dinosaur Teeth and Implications for Paleoecological Turnover through Time. PLoS ONE 8(1): e54329. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054329

- Blasi 2 at Fossilworks.org

Further reading

- Baszio, S. 1997. Investigations on Canadian dinosaurs: systematic palaeontology of isolated dinosaur teeth from the Latest Cretaceous of Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada. Courier Forschunginstitut Senckenberg 196:33-77.

- Sankey, J. T., D. B. Brinkman, M. Guenther, and P. J. Currie. 2002. Small theropod and bird teeth from the Late Cretaceous (Late Campanian) Judith River Group, Alberta. Journal of Paleontology 76(4):751-763.