Horseshoe Canyon Formation

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation is a stratigraphic unit of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin in southwestern Alberta.[3][4] It takes its name from Horseshoe Canyon, an area of badlands near Drumheller.

| Horseshoe Canyon Formation Stratigraphic range: Maastrichtian ~74–67 Ma [1] | |

|---|---|

Horseshoe Canyon Formation at Horsethief Canyon, near Drumheller. The dark bands are coal seams. | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Edmonton Group |

| Underlies | Whitemud Formation |

| Overlies | Bearpaw Formation |

| Thickness | 227 m (745 ft)[2] |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Sandstone |

| Other | Shale, coal |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 51°25′24″N 112°53′18″W |

| Region | Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin |

| Country | |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Horseshoe Canyon |

| Named by | E.J.W. Irish, 1970 |

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation is part of the Edmonton Group and is up to 230 metres (750 ft) thick. It is of Late Cretaceous age, Campanian to early Maastrichtian stage (Edmontonian Land-Mammal Age), and is composed of mudstone, sandstone, carbonaceous shales, and coal seams. A variety of depositional environments are represented in the succession, including floodplains, estuarine channels, and coal swamps, which have yielded a diversity of fossil material. Tidally-influenced estuarine point bar deposits are easily recognizable as Inclined Heterolithic Stratification (IHS). Brackish-water trace fossil assemblages occur within these bar deposits and demonstrate periodic incursion of marine waters into the estuaries.

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation crops out extensively in the area around Drumheller, as well as farther north along the Red Deer River near Trochu and along the North Saskatchewan River in Edmonton.[3] It is overlain by the Battle, Whitemud, and Scollard formations.[4] The Drumheller Coal Zone, located in the lower part of the Horseshoe Canyon Formation, was mined for sub-bituminous coal in the Drumheller area from 1911 to 1979, and the Atlas Coal Mine in Drumheller has been preserved as a National Historic Site.[5] In more recent times, the Horseshoe Canyon Formation has become a major target for coalbed methane (CBM) production.

Dinosaurs found in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation include Albertavenator, Albertosaurus, Anchiceratops, Anodontosaurus, Arrhinoceratops, Atrociraptor, Epichirostenotes, Edmontonia, Edmontosaurus, Hypacrosaurus, Ornithomimus, Pachyrhinosaurus, Parksosaurus, Saurolophus, and Struthiomimus. Other finds have included mammals such as Didelphodon coyi, non-dinosaur reptiles, amphibians, fish, marine and terrestrial invertebrates and plant fossils. Reptiles such as turtles and crocodilians are rare in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation, and this was thought to reflect the relatively cool climate which prevailed at the time. A study by Quinney et al. (2013) however, showed that the decline in turtle diversity, which was previously attributed to climate, coincided instead with changes in soil drainage conditions, and was limited by aridity, landscape instability, and migratory barriers.[6]

Oil/gas production

The Drumheller Coal Zone has been a primary coalbed methane target for industry. In the area between Bashaw and Rockyford, the Coal Zone lies at relatively shallow depths (about 300 metres) and is about 70 to 120 metres thick. It contains 10 to 20 metres of cumulative coal, in up to 20 or more individual thin seams interbedded with sandstone and shale, which combine to make an attractive multi-completion CBM drilling target. In total, it is estimated there are 14 trillion cubic metres (500 tcf) of gas in place in all the coal in Alberta.

Biostratigraphy

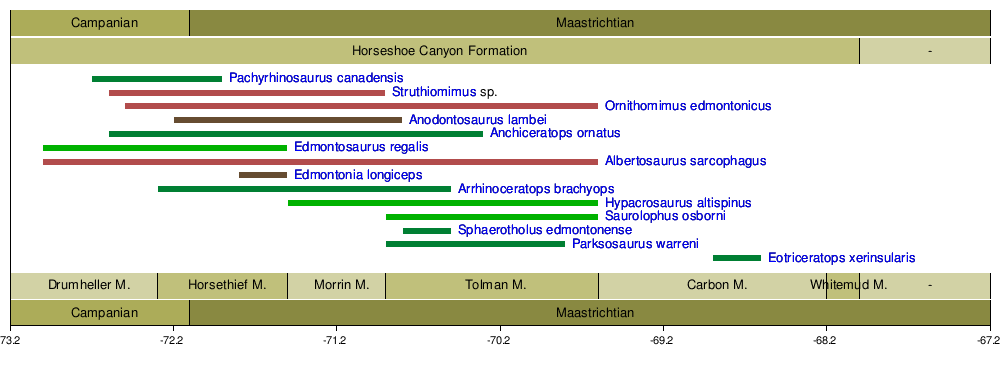

The timeline below follows work by David A. Eberth and Sandra L. Kamo published in 2019.[7]

Dinosaurs

Ankylosaurs

| Ankylosaurids reported from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

Horsethief, Morrin, and lowest Tolman |

| |||||

|

E. longiceps |

Upper Horsethief |

|||||

|

E. tutus |

Walter Coombs (1971) synonymised Anodontosaurus lambei with E. tutus. However, recent studies suggest that Anodontosaurus is distinct enough from Euoplocephalus to be placed in its own genus and species.[8][10] Furthermore, all Horseshoe Canyon Formation ankylosaurine specimens were suggested to be reassigned to Anodontosaurus.[9] | |||||

Maniraptors

| Maniraptors reported from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

A. curriei |

Horsethief |

Frontals, lower jaw, type specimen |

A troodontid |

|||

|

A. borealis |

Upper Tolman |

Limb bones, type specimen |

An alvarezsaurid |

| ||

|

A. pennatus [12] |

Horsethief |

Partial skeleton and skull, type specimen [12] |

A caenagnathid.[12] | |||

|

A. marshalli |

Lower Horsethief |

Partial skull, type specimen |

A dromaeosaurid; teeth indicate it may have been present across all members. | |||

|

E. curriei[13] |

Horsethief, Morrin, and Tolman |

Partial skeleton, type specimen |

A caenagnathid | |||

Marginocephalians

Color key

|

Notes Uncertain or tentative taxa are in small text; |

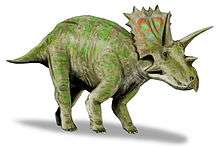

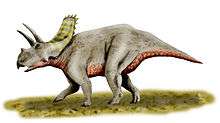

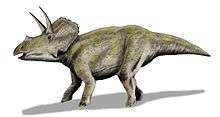

| Marginocephalians reported from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

A. ornatus |

Horsethief, Morrin, and Tolman; may have been present in Drumheller. |

Pachyrhinosaurus lakustai | ||||

|

A. brachyops |

Horsethief and Morrin; may have been present in Drumheller and Tolman. |

"Complete skull."[14] |

||||

|

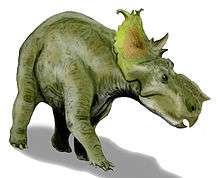

E. xerinsularis |

Carbon |

|||||

|

M. cerorhynchus |

Upper Tolman |

Isolated braincase AMNH 5244. |

||||

|

P. canadensis |

Drumheller and Horsethief |

Ceratopsid | ||||

|

S. edmontonense |

Tolman |

May be a junior synonym of S. buchholtzae | ||||

|

"Almond Formation" ceratopsid |

Unnamed |

Misidentified as Anchiceratops, it is actually a new species, probably the same as a new Pentaceratops-like form from the Almond Formation of Wyoming [15] | ||||

Ornithomimids

Color key

|

Notes Uncertain or tentative taxa are in small text; |

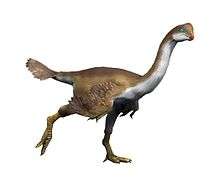

| Ornithomimids reported from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

O. currelli |

Junior synonym of O. edmontonicus | |||||

|

O. edmontonicus |

Drumheller, Horsethief, Morrin, and Tolman |

Several specimens, type specimen |

An ornithomimid |

| ||

|

S. altus |

Drumheller, Horsethief, and Morrin |

An ornithomimid | ||||

Hadrosaurs and thescelosaurs

| Hadrosaurs and thescelosaurids reported from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

E. regalis |

Horsethief; likely present in Drumheller. |

| ||||

|

H. altispinus |

Morrin and Tolman. |

"[Five to ten] articulated skulls, some associated with postcrania, isolated skull elements, isolated postcranial elements, many individuals, embryo to adult."[16] |

||||

|

P. warreni |

Tolman |

Type specimen |

||||

|

S. osborni |

Upper Morrin and Tolman. |

"Complete skull and skeleton, [two] complete skulls."[16] |

||||

Tyrannosaurs

Color key

|

Notes Uncertain or tentative taxa are in small text; |

| Theropods reported from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

A. arctunguis |

Junior synonym of A. sarcophagus |

| ||||

|

A. sarcophagus |

Horsethief, Morrin, and Tolman; likely present in Drumheller and Carbon. |

Several skeletons and partial skeletons, type specimen |

A tyrannosaurid | |||

|

D. sp. |

Suggested from the skeleton of an immature tyrannosaurid (CMN 11315), thorough analysis of this specimen supports a referral to A. sarcophagus.[17] An isolated maxilla and teeth from an Edmontosaurus bonebed were also mistakenly referred to Daspletosaurus, however all the tyrannosaurid material in the bonebed was confirmed to belong to A. sarcophagus.[18] | |||||

Other Animals

Mammals

Color key

|

Notes Uncertain or tentative taxa are in small text; |

| Mammals reported from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

D. coyi |

||||||

Other Reptiles

Color key

|

Notes Uncertain or tentative taxa are in small text; |

| Reptiles reported from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

S. mccabei |

"a skull, partial lower jaws, and partial postcranial skeleton" |

An alligatoroid |

||||

|

C. albertensis |

"partial skeleton with partial skull" |

|||||

|

L. ultimus |

"a partial skeleton" |

a plesiosaur of uncertain classification |

||||

|

B. morrinensis |

"nearly complete shell" |

|||||

Fish

Color key

|

Notes Uncertain or tentative taxa are in small text; |

| Fish reported from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

Horseshoeichthys[24] |

H. armaserratus |

An ellimmichthyiform |

||||

See also

- List of dinosaur-bearing rock formations

References

- Claessens, L. & Mark A. Loewen, M.A. (2015). A redescription of Ornithomimus velour Marsh, 1890 (Dinosauria, Theropoda). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (advance online publication). doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1034593

- Lexicon of Canadian Geological Units. "Horseshoe Canyon Formation". Archived from the original on 2012-07-07. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- Prior, G. J., Hathaway, B., Glombick, P.M., Pana, D.I., Banks, C.J., Hay, D.C., Schneider, C.L., Grobe, M., Elgr, R., and Weiss, J.A. (2013). "Bedrock Geology of Alberta. Alberta Geological Survey, Map 600". Archived from the original on 2013-07-05. Retrieved 2013-08-13.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mossop, G.D. and Shetsen, I., (compilers), Canadian Society of Petroleum Geologists (1994). "The Geological Atlas of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin, Chapter 24: Upper Cretaceous and Tertiary strata of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin". Archived from the original on 2013-07-21. Retrieved 2013-08-01.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Mine History". Atlas Coal Mine National Historic Site. Archived from the original on 23 August 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- Quinney, Annie; Therrien, François; Zelenitsky, Darla K.; Eberth, David A. (2013). "Palaeoenvironmental and palaeoclimatic reconstruction of the Upper Cretaceous (late Campanian–early Maastrichtian) Horseshoe Canyon Formation, Alberta, Canada". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 371: 26–44. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.12.009.

- Eberth, David A.; Kamo, Sandra (2019). "High-precision U-Pb CA-ID-TIMS dating and chronostratigraphy of the dinosaur-rich Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Upper Cretaceous, Campanian–Maastrichtian), Red Deer River valley, Alberta, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. doi:10.1139/cjes-2019-0019.

- Penkalski, P. (2013). "A new ankylosaurid from the late Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of Montana, USA". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. doi:10.4202/app.2012.0125.

- Arbour, Victoria (2010). "A Cretaceous armoury: Multiple ankylosaurid taxa in the Late Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada and Montana, USA". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (Supplement 2): 55A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.10411819.

- Penkalski, P.; Blows, W. T. (2013). "Scolosaurus cutleri (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 50: 130110052638009. doi:10.1139/cjes-2012-0098.

- Evans, D.C., Cullen, T.M., Larson, D.W., and Rego, A. "A new species of troodontid theropod (Dinosauria: Maniraptora) from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Maastrichtian) of Alberta, Canada." Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Early Online: 813-826. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.1139/cjes-2017-0034

- Gregory F. Funston; Philip J. Currie (2016). "A new caenagnathid (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, Canada, and a reevaluation of the relationships of Caenagnathidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Online edition: e1160910. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1160910.

- Robert M. Sullivan; Steven E. Jasinski; Mark P.A. Van Tomme (2011). "A new caenagnathid Ojoraptorsaurus boerei, n. gen., n. sp. (Dinosauria, Oviraptorosauria), from the Upper Ojo Alamo Formation (Naashoibito Member), San Juan Basin, New Mexico" (PDF). Fossil Record 3. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 53: 418–428.

- "Table 23.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 495.

- Farke, A. A. "Cranial osteology and phylogenetic relationships of the chasmosaurine ceratopsid Torosaurus latus", pp. 235-257. In K. Carpenter (ed.). Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Indiana Univ. Press (Bloomington), 2006.

- "Table 20.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 441.

- Mallon, J.C.; Bura, J.R.; Currie, P.J. (2019). "A Problematic Tyrannosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) Skeleton and Its Implications for Tyrannosaurid Diversity in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of Alberta". The Anatomical Record. doi:10.1002/ar.24199. PMC 7079176. PMID 31254458.

- Torices, A.; Reichel, M.; Currie, P.J. (2014). "Multivariate analysis of isolated tyrannosaurid teeth from the Danek Bonebed, Horseshoe Canyon Formation, Alberta, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 51 (11): 1045–1051. doi:10.1139/cjes-2014-0072.

- R. C. Fox and B. G. Naylor. 1986. A new species of Didelphodon Marsh (Marsupialia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Alberta, Canada: paleobiology and phylogeny. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 172(3):357-380 [J. Alroy/J. Alroy/M. Carrano]

- X.-C. Wu, D. B. Brinkman, and A. P. Russell. 1996. A new alligator from the Upper Cretaceous of Canada and the relationships of early eusuchians. Palaeontology 39(2):351-375 [P. Mannion/P. Mannion]

- K. -Q. Gao and R. C. Fox. 1998. New choristoderes (Reptilia: Diapsida) from the Upper Cretaceous and Palaeocene, Alberta and Saskatchewan, Canada, a phylogenetic relationships of Choristodera. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 124:303-353 [R. Benson/R. Benson]

- B. Brown. 1913. A new plesiosaur, Leurospondylus, from the Edmonton Cretaceous of Alberta. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 32(40):605-615 [M. Carrano/H. Street]

- Mallon, Jordan C.; Brinkman, Donald B. (2018). "Basilemys morrinensis, a new species of nanhsiungchelyid turtle from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of Alberta, Canada". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38: e1431922. doi:10.1080/02724634.2018.1431922.

- Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 2010, 47(9): 1183-1196

Bibliography

- Makovicky, P. J., 2001, A Montanoceratops cerorhynchus (Dinosauria: Ceratopsia) braincase from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, pp. 243–262.

- Varricchio, D. J. 2001. Late Cretaceous oviraptorosaur (Theropoda) dinosaurs from Montana. pp. 42–57 in D. H. Tanke and K. Carpenter (eds.), Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press, Indianapolis, Indiana.

- Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.