Pauravas

Pauravas was an ancient Indian dynasty in the northwest Indian subcontinent (present-day India and Pakistan) which was ruled by King Porus.

Origins

The origins of the Pauravas is still doubted. Modern scholars are of the theory that Porus was a descendant of the Puru tribe, however the theory was debunked. [1] According to historian Ishwari Prasad, Porus might have been a Yaduvanshi Shurasena. He argued that Porus' vanguard soldiers carried a banner of Heracles whom Megasthenes—who travelled to India after Porus had been supplanted by Chandragupta—explicitly identified with the Shurasenas of Mathura. This Heracles of Megasthenes and Arrian (the so called Megasthenes' Herakles) has been identified by some scholars as Krishna and by others as his elder brother Baladeva, who were both the ancestors and patron deities of Shoorsainis.[2][3][4][5] Iswhari Prashad and others, following his lead, found further support of this conclusion in the fact that a section of Shurasenas were supposed to have migrated westwards to Punjab and modern Afghanistan from Mathura and Dvārakā, after Krishna walked to heaven and had established new kingdoms there.[6][7]

Porus as Paurava

Alexander's adversary Porus is considered "Paurava" due to the nearness of the name Porus to Paurava. However, in Indian literature and history Porus is not mentioned anywhere, and the Pauravas referred to in Indian literature are a much older kingdom per Purana and Mahabharata's writing.

The Persian kings Darius and Xerxes of the Achaemenid Empire had no claim beyond the present-day Khyber Pass and had no knowledge of the Punjab region according to Strabo.[8] Similarly, the people of the tributary rivers of the Indus, modern-day Punjab, also had never heard of the past Persian kings along with the people of the Indus, who according to Megasthenes were not even aware of the vast Achaemenid Empire.[9]

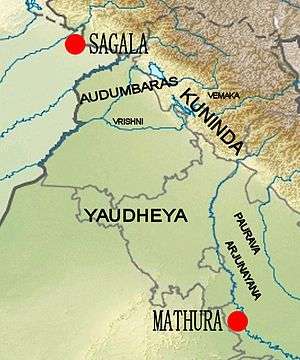

At the time of Alexander's invasion, the Pauravas were situated on or near the Jhelum River,until the Chenab River. This was not only the extant of Porus' Kingdom, but was also the eastern limit of the Macedonian Empire.[9]

Alexander defeated Porus at the Battle of the Hydaspes. Due to Porus' display in the battlefield, Alexander appointed him as a Macedonian satrap and additionally granted Porus more land in the Indus. Alexander was initially set on venturing further into India. However, the battle of Hydaspes against Porus curbed this aspiration. Alexander's army would mutiny when opposed to the Nanda Empire and their subordinate Gangaridai. According to the Greek historian Plutarch, the previous conflict against Porus' much smaller army dissuaded their advance.

As for the Macedonians, however, their struggle with Porus blunted their courage and stayed their further advance into India. For having had all they could do to repulse an enemy who mustered only twenty thousand infantry and two thousand horse, they violently opposed Alexander when he insisted on crossing the river Ganges also, the width of which, as they learned, was thirty-two furlongs, its depth a hundred fathoms, while its banks on the further side were covered with multitudes of men-at-arms and horsemen and elephants. For they were told that the kings of the Ganderites and Praesii were awaiting them with eighty thousand horsemen, two hundred thousand footmen, eight thousand chariots, and six thousand fighting elephants.

— Plutarch, Plutarch's Lives, Plutarch, Alexander, 62

Alexander died on his way back from India.[9] The instability that ensued after Alexander's death resulted in a power struggle and dramatic changes in governance. Porus was soon assassinated by the Macedonia general Eudemus. By 316 BC, the Macedonian entity was conquered by Chandragupta Maurya, a young adventurer, who later conquered the Nanda Empire and founded the Indian Maurya Empire. After engaging and winning the Seleucid–Mauryan war for supremacy over the Indus Valley, Chandragupta gained controlled of modern-day Punjab and Afghanistan. This set the foundations of the Mauryan Empire, which would become the largest empire in the Indian subcontinent.[10]

Post-Mauryan Empire

It appears that the Pauravas were annexed by the militant Yaudheya Republic.[11] Following the disintegration of the Mauryan Empire, many regional entities emerged. The Taleshwar copper plates found in Almora, stated Brahmapura Kingdom rulers belonged to the royal lineage of Pauravas.[11] The reinstated Paurava dynasty of Brahmapur was founded by Vishnuverman, and flourished in the 7th century AD. It is stated that these kings were brahminical in habitat and practices.[12]

References

- Nonica Datta, ed. (2003). Indian History: Ancient and medieval. Encyclopaedia Britannica / Popular Prakashan. p. 222. ISBN 978-81-7991-067-2.

Not known in Indian sources, the name Porus has been conjecturally interpreted as standing for Paurava, that is, the ruler of the Purus, a clan known in that region from ancient Vedic times.

- Proceedings, pp 72, Indian History Congress, Published 1957

- According to Arrian, Diodorus, and Strabo, Megasthenes described an Indian tribe called Sourasenoi, who especially worshipped Herakles in their land, and this land had two cities, Methora and Kleisobora, and a navigable river, the Jobares. As was common in the ancient period, the Greeks sometimes described foreign gods in terms of their own divinities, and there is a little doubt that the Sourasenoi refers to the Shurasenas, a branch of the Yadu dynasty to which Krishna belonged; Herakles to Krishna, or Hari-Krishna: Mehtora to Mathura, where Krishna was born; Kleisobora to Krishnapura, meaning "the city of Krishna"; and the Jobares to the Yamuna, the famous river in the Krishna story. Quintus Curtius also mentions that when Alexander the Great confronted Porus, Porus's soldiers were carrying an image of Herakles in their vanguard.Krishna: a sourcebook, pp 5, Edwin Francis Bryant, Oxford University Press US, 2007

- Chandragupta Maurya: a gem of Indian history, pp 76, Purushottam Lal Bhargava, Edition: 2, illustrated, Published by D.K. Printworld, 1996

- A Comprehensive History of India: The Mauryas & Satavahanas, pp 383, edited by K.A. Nilakanta Sastri, Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta Sastri, Bharatiya Itihas Parishad, Published by Orient Longmans, 1992, Original from the University of California

- "Actually , the legend reports a westward march of the Yadus (MBh. 1.13.49, 65) from Mathura, while the route from Mathura to Dvaraka southward through a desert. This part of the Krsna legend could be brought to earth by digging at Dvaraka, but also digging at Darwaz in Afghanistan, whose name means the same thing and which is the more probable destination of refugees from Mathura..." Introduction to the study of Indian history, pp 125, D D Kosambi, Publisher: [S.l.] : Popular Prakashan, 1999

- Gazetteer of the Dera Ghazi Khan District, Lahore, "Civil and Military Gazette" Press, 1898, p. 52,

It seems, therefore, most reasonable to conclude that the name is simply the seat of Purrus or Porus, the name of a King or family of kings ... There are no authentic records of tribes seated about Peshawar before the time of Mahmud, beyond established fact of their being of Indian origin; it not an improbable conjecture that they descended from the race of Yadu who were either expelled or voluntarily emigrated from Gujrat, 1100 years before Christ, and who afterwards found Kandhar and the hills of Cabul (Kabul) from whom, indeed, some would derive the Jaduns now residing in the hills of north of Yusafjai...

- Frank L. Holt (24 November 2003). Alexander the Great and the Mystery of the Elephant Medallions. University of California Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-520-23881-7.

- Graham Phillips (31 March 2012). Alexander The Great. Ebury Publishing. pp. 129–131. ISBN 978-0-7535-3582-0.

- Arthur A. MacDonell (28 March 2014). A History of Sanskrit Literature (Illustrated). Lulu.com. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-304-98862-1.

- Saklani, Dinesh Prasad (1998). Ancient Communities of the Himalaya. Indus Publishing. ISBN 9788173870903.

- https://books.google.co.in/books?id=GEOwDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT25&lpg=PT25&dq=brahmapur+pauravas&source=bl&ots=xcc6IkJDia&sig=ACfU3U3qpeVV5gSnB9ftgUfI6gEPRkG0TQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiZvouT0JTqAhUtyDgGHYapD2cQ6AEwAHoECAoQAQ#v=onepage&q=brahmapur%20pauravas&f=false