Portrait painting

Portrait painting is a genre in painting, where the intent is to represent a specific human subject. The term 'portrait painting' can also describe the actual painted portrait. Portraitists may create their work by commission, for public and private persons, or they may be inspired by admiration or affection for the subject. Portraits often serve as important state and family records, as well as remembrances.

- See portrait for more about the general topic of portraits.

Historically, portrait paintings have primarily memorialized the rich and powerful. Over time, however, it became more common for middle-class patrons to commission portraits of their families and colleagues. Today, portrait paintings are still commissioned by governments, corporations, groups, clubs, and individuals. In addition to painting, portraits can also be made in other media such as prints (including etching and lithography), photography, video and digital media.

It might seem obvious that a painted portrait is intended to achieve a likeness of the sitter that is recognisable to those who have seen them, and ideally is a very good record of their appearance. In fact this concept has been slow to grow, and it took centuries for artists in different traditions to acquire the distinct skills for painting a good likeness.

Technique and practice

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

A well-executed portrait is expected to show the inner essence of the subject (from the artist's point of view) or a flattering representation, not just a literal likeness. As Aristotle stated, "The aim of Art is to present not the outward appearance of things, but their inner significance; for this, not the external manner and detail, constitutes true reality."[1] Artists may strive for photographic realism or an impressionistic similarity in depicting their subject, but this differs from a caricature which attempts to reveal character through exaggeration of physical features. The artist generally attempts a representative portrayal, as Edward Burne-Jones stated, "The only expression allowable in great portraiture is the expression of character and moral quality, not anything temporary, fleeting, or accidental."[2]

In most cases, this results in a serious, closed lip stare, with anything beyond a slight smile being rather rare historically. Or as Charles Dickens put it, "there are only two styles of portrait painting: the serious and the smirk."[3] Even given these limitations, a full range of subtle emotions is possible from quiet menace to gentle contentment. However, with the mouth relatively neutral, much of the facial expression needs to be created through the eyes and eyebrows. As author and artist Gordon C. Aymar states, "the eyes are the place one looks for the most complete, reliable, and pertinent information" about the subject. And the eyebrows can register, "almost single-handedly, wonder, pity, fright, pain, cynicism, concentration, wistfulness, displeasure, and expectation, in infinite variations and combinations."[4]

Portrait painting can depict the subject "full-length" (the whole body), "half-length" (from head to waist or hips), "head and shoulders" (bust), or just the head. The subject's head may turn from "full face" (front view) to profile (side view); a "three-quarter view" ("two-thirds view") is somewhere in between, ranging from almost frontal to almost profile (the fraction is the sum of the profile [one-half of the face] plus the other side's "quarter-face";[5] alternatively, each side is considered a third). Occasionally, artists have created composites with views from multiple directions, as with Anthony van Dyck's triple portrait of Charles I in Three Positions.[6] There are even a few portraits where the front of the subject is not visible at all. Andrew Wyeth's Christina's World (1948) is a famous example, where the pose of the disabled girl – with her back turned to the viewer – integrates with the setting in which she is placed to convey the artist's interpretation.[7]

Among the other possible variables, the subject can be clothed or nude; indoors or out; standing, seated, reclining; even horse-mounted. Portrait paintings can be of individuals, couples, parents and children, families, or collegial groups. They can be created in various media including oils, watercolor, pen and ink, pencil, charcoal, pastel, and mixed media. Artists may employ a wide-ranging palette of colors, as with Pierre-Auguste Renoir's Mme. Charpentier and her children, 1878 or restrict themselves to mostly white or black, as with Gilbert Stuart's Portrait of George Washington (1796).

Sometimes, the overall size of the portrait is an important consideration. Chuck Close's enormous portraits created for museum display differ greatly from most portraits designed to fit in the home or to travel easily with the client. Frequently, an artist takes into account where the final portrait will hang and the colors and style of the surrounding décor.[8]

Creating a portrait can take considerable time, usually requiring several sittings. Cézanne, on one extreme, insisted on over 100 sittings from his subject.[9] Goya on the other hand, preferred one long day's sitting.[10] The average is about four.[11] Portraitists sometimes present their sitters with a portfolio of drawings or photos from which a sitter would select a preferred pose, as did Sir Joshua Reynolds. Some, such as Hans Holbein the Younger make a drawing of the face, then complete the rest of the painting without the sitter.[12] In the 18th century, it would typically take about one year to deliver a completed portrait to a client.[13]

Managing the sitter's expectations and mood is a serious concern for the portrait artist. As to the faithfulness of the portrait to the sitter's appearance, portraitists are generally consistent in their approach. Clients who sought out Sir Joshua Reynolds knew that they would receive a flattering result, while sitters of Thomas Eakins knew to expect a realistic, unsparing portrait. Some subjects voice strong preferences, others let the artist decide entirely. Oliver Cromwell famously demanded that his portrait show "all these roughnesses, pimples, warts, and everything as you see me, otherwise I will never pay a farthing for it."[14]

After putting the sitter at ease and encouraging a natural pose, the artist studies his subject, looking for the one facial expression, out of many possibilities, that satisfies his concept of the sitter's essence. The posture of the subject is also carefully considered to reveal the emotional and physical state of the sitter, as is the costume. To keep the sitter engaged and motivated, the skillful artist will often maintain a pleasant demeanor and conversation. Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun advised fellow artists to flatter women and compliment their appearance to gain their cooperation at the sitting.[14]

Central to the successful execution of the portrait is a mastery of human anatomy. Human faces are asymmetrical and skillful portrait artists reproduce this with subtle left-right differences. Artists need to be knowledgeable about the underlying bone and tissue structure to make a convincing portrait.

For complex compositions, the artist may first do a complete pencil, ink, charcoal, or oil sketch which is particularly useful if the sitter's available time is limited. Otherwise, the general form then a rough likeness is sketched out on the canvas in pencil, charcoal, or thin oil. In many cases, the face is completed first, and the rest afterwards. In the studios of many of the great portrait artists, the master would do only the head and hands, while the clothing and background would be completed by the principal apprentices. There were even outside specialists who handled specific items such as drapery and clothing, such as Joseph van Aken[15] Some artists in past times used lay-figures or dolls to help establish and execute the pose and the clothing.[16] The use of symbolic elements placed around the sitter (including signs, household objects, animals, and plants) was often used to encode the painting with the moral or religious character of the subject, or with symbols representing the sitter's occupation, interests, or social status. The background can be totally black and without content or a full scene which places the sitter in their social or recreational milieu.

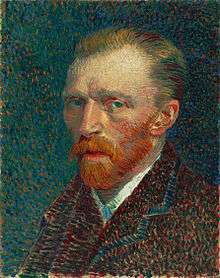

Self-portraits are usually produced with the help of a mirror, and the finished result is a mirror-image portrait, a reversal of what occurs in a normal portrait when sitter and artist are opposite each other. In a self-portrait, a righted handed artist would appear to be holding a brush in the left hand, unless the artist deliberately corrects the image or uses a second reversing mirror while painting.

Occasionally, the client or the client's family is unhappy with the resulting portrait and the artist is obliged to re-touch it or do it over or withdraw from the commission without being paid, suffering the humiliation of failure. Jacques-Louis David celebrated Portrait of Madame Récamier, wildly popular in exhibitions, was rejected by the sitter, as was John Singer Sargent's notorious Portrait of Madame X. John Trumbull's full-length portrait, General George Washington at Trenton, was rejected by the committee that commissioned it.[17] The famously prickly Gilbert Stuart once replied to a client's dissatisfaction with his wife's portrait by retorting, "You brought me a potato, and you expect a peach!"[18]

A successful portrait, however, can gain the lifelong gratitude of a client. Count Balthazar was so pleased with the portrait Raphael had created of his wife that he told the artist, "Your image…alone can lighten my cares. That image is my delight; I direct my smiles to it, it is my joy."[19]

History

Ancient world

Portraiture's roots are likely found in prehistoric times, although few of these works survive today. In the art of the ancient civilizations of the Fertile Crescent, especially in Egypt, depictions of rulers and rulers as gods abound. However, most of these were done in a highly stylized fashion, and most in profile, usually on stone, metal, clay, plaster, or crystal. Egyptian portraiture placed relatively little emphasis on likeness, at least until the period of Akhenaten in the 14th century BC. Portrait painting of notables in China probably goes back to over 1000 BC, though none survive from that age. Existing Chinese portraits go back to about 1000 AD,[20] but did not place much emphasis on likeness until some time after that.

From literary evidence we know that ancient Greek painting included portraiture, often highly accurate if the praises of writers are to be believed, but no painted examples remain. Sculpted heads of rulers and famous personalities like Socrates survive in some quantity, and like the individualized busts of Hellenistic rulers on coins, show that Greek portraiture could achieve a good likeness, and subjects, at least of literary figures, were depicted with relatively little flattery – Socrates' portraits show why he had a reputation for being ugly. The successors of Alexander the Great began the practice of adding his head (as a deified figure) to their coins, and were soon using their own.

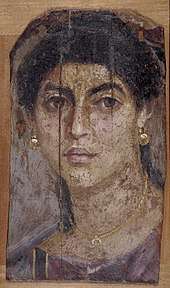

Roman portraiture adopted traditions of portraiture from both the Etruscans and Greeks, and developed a very strong tradition, linked to their religious use of ancestor portraits, as well as Roman politics. Again, the few painted survivals, in the Fayum portraits, Tomb of Aline and the Severan Tondo, all from Egypt under Roman rule, are clearly provincial productions that reflect Greek rather than Roman styles, but we have a wealth of sculpted heads, including many individualized portraits from middle-class tombs, and thousands of types of coin portraits.

Much the largest group of painted portraits are the funeral paintings that survived in the dry climate of Egypt's Fayum district (see illustration, below), dating from the 2nd to 4th century AD. These are almost the only paintings of the Roman period that have survived, aside from frescos, though it is known from the writings of Pliny the Elder that portrait painting was well established in Greek times, and practiced by both men and women artists.[21] In his times, Pliny complained of the declining state of Roman portrait art, "The painting of portraits which used to transmit through the ages the accurate likenesses of people, has entirely gone out…Indolence has destroyed the arts." [22][23] These full-face portraits from Roman Egypt are fortunate exceptions. They present a somewhat realistic sense of proportion and individual detail (though the eyes are generally oversized and the artistic skill varies considerably from artist to artist). The Fayum portraits were painted on wood or ivory in wax and resin colors (encaustic) or with tempera, and inserted into the mummy wrapping, to remain with the body through eternity.

While free-standing portrait painting diminished in Rome, the art of the portrait flourished in Roman sculptures, where sitters demanded realism, even if unflattering. During the 4th century, the sculpted portrait dominated, with a retreat in favor of an idealized symbol of what that person looked like. (Compare the portraits of Roman Emperors Constantine I and Theodosius I) In the Late Antique period the interest in an individual likeness declined considerably, and most portraits in late Roman coins and consular diptychs are hardly individualized at all, although at the same time Early Christian art was evolving fairly standardized images for the depiction of Jesus and the other major figures in Christian art, such as John the Baptist, and Saint Peter.

Middle Ages

Most early medieval portraits were donor portraits, initially mostly of popes in Roman mosaics, and illuminated manuscripts, an example being a self-portrait by the writer, mystic, scientist, illuminator, and musician Hildegard of Bingen (1152).[24] As with contemporary coins, there was little attempt at a likeness. Stone tomb monuments spread in the Romanesque period. Between 1350–1400, secular figures began to reappear in frescos and panel paintings, such as in Master Theodoric's Charles IV receiving fealty,[25] and portraits once again became clear likenesses.

Around the end of the century, the first oil portraits of contemporary individuals, painted on small wood panels, emerged in Burgundy and France, first as profiles, then in other views. The Wilton Diptych of ca. 1400 is one of two surviving panel portraits of Richard II of England, the earliest English King for whom we have contemporary examples.

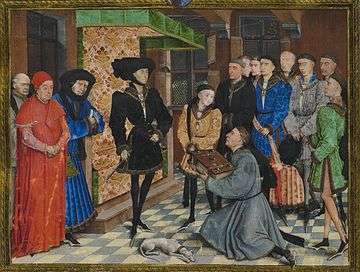

At the end of the Middle Ages in the 15th century, Early Netherlandish painting was key to the development of the individualized portrait. Masters included Jan van Eyck, Robert Campin and Rogier van der Weyden, among others. Rather small panel painting portraits, less than half life-size, were commissioned, not only of figures from the court, but what appear from their relatively plain dress to be wealthy townspeople. Miniatures in illuminated manuscripts also included individualized portraits, usually of the commissioner. In religious paintings, portraits of donors began to be shown as present, or participate in the main sacred scenes shown, and in more private court images subjects even appeared as significant figures such as the Virgin Mary.

Robert Campin (c. 1375 – 1444), Portrait of a Young Woman (paired with her husband), 1430–1435. Van der Weyden's style was founded on Campin's.

Robert Campin (c. 1375 – 1444), Portrait of a Young Woman (paired with her husband), 1430–1435. Van der Weyden's style was founded on Campin's. Arnolfini Portrait, by Jan van Eyck, 1434

Arnolfini Portrait, by Jan van Eyck, 1434

One of the earliest stand-alone self-portraits, Jean Fouquet, c. 1450

One of the earliest stand-alone self-portraits, Jean Fouquet, c. 1450

Renaissance

.jpg)

Partly out of interest in the natural world and partly out of interest in the classical cultures of ancient Greece and Rome, portraits—both painted and sculpted—were given an important role in Renaissance society and valued as objects, and as depictions of earthly success and status. Painting in general reached a new level of balance, harmony, and insight, and the greatest artists (Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael) were considered "geniuses", rising far above the tradesman status to valued servants of the court and the church.[26]

If the poet says that he can inflame men with love…

the painter has the power to do the same…

in that he can place in front of the lover

the true likeness of one who is beloved,

often making him kiss and speak to it.

–Leonardo de' Vinci[27]

Many innovations in the various forms of portraiture evolved during this fertile period. The tradition of the portrait miniature began, which remained popular until the age of photography, developing out of the skills of painters of the miniatures in illuminated manuscripts. Profile portraits, inspired by ancient medallions, were particularly popular in Italy between 1450 and 1500. Medals, with their two–sided images, also inspired a short-lived vogue for two-sided paintings early in the Renaissance.[28] Classical sculpture, such as the Apollo Belvedere, also influenced the choice of poses utilized by Renaissance portraitists, poses that have continued in usage through the centuries.[29] Leonardo's Ginevra de' Benci (c. 1474–8) is one of the first known three-quarter-view portraits in Italian art.[27]

Northern European artists led the way in realistic portraits of secular subjects. The greater realism and detail of the Northern artists during the 15th century was due in part to the finer brush strokes and effects possible with oil colors, while the Italian and Spanish painters were still using tempera. Among the earliest painters to develop oil technique was Jan van Eyck. Oil colors can produce more texture and grades of thickness, and can be layered more effectively, with the addition of increasingly thick layers one over another (known by painters as ‘fat over lean’). Also, oil colors dry more slowly, allowing the artist to make changes readily, such as altering facial details. Antonello da Messina was one of the first Italians to take advantage of oil. Trained in Belgium, he settled in Venice around 1475, and was a major influence on Giovanni Bellini and the Northern Italian school.[30] During the 16th century, oil as a medium spread in popularity throughout Europe, allowing for more sumptuous renderings of clothing and jewelry. Also affecting the quality of the images, was the switch from wood to canvas, starting in Italy in the early part of the 16th century and spreading to Northern Europe over the next century. Canvas resists cracking better than wood, holds pigments better, and needs less preparation―but it was initially much scarcer than wood.

Early on, the Northern Europeans abandoned the profile, and started producing portraits of realistic volume and perspective. In the Netherlands, Jan van Eyck was a leading portraitist. The Arnolfini Marriage (1434, National Gallery, London) is a landmark of Western art, an early example of a full-length couple portrait, superbly painted in rich colors and exquisite detail. But equally important, it showcases the newly developed technique of oil painting pioneered by van Eyck, which revolutionized art, and spread throughout Europe.[31]

Leading German portrait artists including Lucas Cranach, Albrecht Dürer, and Hans Holbein the Younger who all mastered oil painting technique. Cranach was one of the first artists to paint life-sized full-length commissions, a tradition popular from then on.[32] At that time, England had no portrait painters of the first rank, and artists like Holbein were in demand by English patrons.[33] His painting of Sir Thomas More (1527), his first important patron in England, has nearly the realism of a photograph.[34] Holbein made his great success painting the royal family, including Henry VIII. Dürer was an outstanding draftsman and one of the first major artists to make a sequence of self-portraits, including a full-face painting. He also placed his self-portrait figure (as an onlooker) in several of his religious paintings.[35] Dürer began making self-portraits at the age of thirteen.[36] Later, Rembrandt would amplify that tradition.

In Italy, Masaccio led the way in modernizing the fresco by adopting more realistic perspective. Filippo Lippi paved the way in developing sharper contours and sinuous lines[37] and his pupil Raphael extended realism in Italy to a much higher level in the following decades with his monumental wall paintings.[38] During this time, the betrothal portrait became popular, a particular specialty of Lorenzo Lotto.[39] During the early Renaissance, portrait paintings were generally small and sometimes covered with protective lids, hinged or sliding.[40]

During the Renaissance, the Florentine and Milanese nobility, in particular, wanted more realistic representations of themselves. The challenge of creating convincing full and three-quarter views stimulated experimentation and innovation. Sandro Botticelli, Piero della Francesca, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Lorenzo di Credi, and Leonardo da Vinci and other artists expanded their technique accordingly, adding portraiture to traditional religious and classical subjects. Leonardo and Pisanello were among the first Italian artists to add allegorical symbols to their secular portraits.[38]

One of best-known portraits in the Western world is Leonardo da Vinci's painting titled Mona Lisa, named for Lisa del Giocondo,[41][42][43] a member of the Gherardini family of Florence and Tuscany and the wife of wealthy Florentine silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo. The famous "Mona Lisa smile" is an excellent example of applying subtle asymmetry to a face. In his notebooks, Leonardo advises on the qualities of light in portrait painting:

A very high degree of grace in the light and shadow is added to the faces of those who sit in the doorways of rooms that are dark, where the eyes of the observer see the shadowed part of the face obscured by the shadows of the room, and see the lighted part of the face with the greater brilliance which the air gives it. Through this increase in the shadows and the lights, the face is given greater relief.[44]

Leonardo was a student of Verrocchio. After becoming a member of the Guild of Painters, he began to accept independent commissions. Owing to his wide-ranging interests and in accordance with his scientific mind, his output of drawings and preliminary studies is immense though his finished artistic output is relatively small. His other memorable portraits included those of noblewomen Ginevra de’ Benci and Cecilia Gallerani.[45]

Raphael's surviving commission portraits are far more numerous than those of Leonardo, and they display a greater variety of poses, lighting, and technique. Rather than producing revolutionary innovations, Raphael's great accomplishment was strengthening and refining the evolving currents of Renaissance art.[46] He was particularly expert in the group portrait. His masterpiece the School of Athens is one of the foremost group frescoes, containing likenesses of Leonardo, Michelangelo, Bramante, and Raphael himself, in the guise of ancient philosophers.[47] It was not the first group portrait of artists. Decades earlier, Paolo Uccello had painted a group portrait including Giotto, Donatello, Antonio Manetti, and Brunelleschi.[35] As he rose in prominence, Raphael became a favorite portraitist of the popes. While many Renaissance artists eagerly accepted portrait commissions, a few artists refused them, most notably Raphael's rival Michelangelo, who instead undertook the huge commissions of the Sistine Chapel.[38]

In Venice around 1500, Gentile Bellini and Giovanni Bellini dominated portrait painting. They received the highest commissions from the leading officials of the state. Bellini's portrait of Doge Loredan is considered to be one of the finest portraits of the Renaissance and ably demonstrates the artist's mastery of the newly arrived techniques of oil painting.[48] Bellini is also one of the first artists in Europe to sign their work, though he rarely dated them.[49] Later in the 16th century, Titian assumed much the same role, particularly by expanding the variety of poses and sittings of his royal subjects. Titian was perhaps the first great child portraitist.[50] After Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese became leading Venetian artists, helping the transition to Italian Mannerism. The Mannerists contributed many exceptional portraits that emphasized material richness and elegantly complex poses, as in the works of Agnolo Bronzino and Jacopo da Pontormo. Bronzino made his fame portraying the Medici family. His daring portrait of Cosimo I de' Medici, shows the austere ruler in armor with a wary eye gazed to his extreme right, in sharp contrast to most royal paintings which show their sitters as benign sovereigns.[51] El Greco, who trained in Venice for twelve years, went in a more extreme direction after his arrival in Spain, emphasizing his "inner vision" of the sitter to the point of diminishing the reality of physical appearance.[52] One of the best portraitists of 16th-century Italy was Sofonisba Anguissola from Cremona, who infused her individual and group portraits with new levels of complexity.

Court portraiture in France began when Flemish artist Jean Clouet painted his opulent likeness of Francis I of France around 1525.[53] King Francis was a great patron of artists and an avaricious art collector who invited Leonardo da Vinci to live in France during his later years. The Mona Lisa stayed in France after Leonardo died there.[53]

Pisanello, perhaps Ginevra d'Este, c. 1440

Pisanello, perhaps Ginevra d'Este, c. 1440 Young Man by Sandro Botticelli, c. 1483. An early Italian full-face pose.

Young Man by Sandro Botticelli, c. 1483. An early Italian full-face pose.- Possibly Raphael, c. 1518, Isabel de Requesens. The High Renaissance style and format were enormously influential for later grand portraits.

.jpg) Christiane von Eulenau by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1534

Christiane von Eulenau by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1534 Lucrezia Panciatichi, by Agnolo Bronzino, 1540

Lucrezia Panciatichi, by Agnolo Bronzino, 1540

Maarten van Heemskerck (1498–1574), Family of Pieter Jan Foppesz, prior to c.1532, considered the first family portrait, in Dutch portraiture.[54]

Maarten van Heemskerck (1498–1574), Family of Pieter Jan Foppesz, prior to c.1532, considered the first family portrait, in Dutch portraiture.[54] Charles V by Titian, 1548, a seminal equestrian portrait.

Charles V by Titian, 1548, a seminal equestrian portrait..jpg) The Armada Portrait of Elizabeth I of England, c. 1588. The stylised portraiture of Elizabeth I of England was unique in Europe.

The Armada Portrait of Elizabeth I of England, c. 1588. The stylised portraiture of Elizabeth I of England was unique in Europe.

Baroque and Rococo

_van_het_Amsterdamse_lakenbereidersgilde_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

During the Baroque and Rococo periods (17th and 18th centuries, respectively), portraits became even more important records of status and position. In a society dominated increasingly by secular leaders in powerful courts, images of opulently attired figures were a means to affirm the authority of important individuals. Flemish painters Sir Anthony van Dyck and Peter Paul Rubens excelled at this type of portraiture, while Jan Vermeer produced portraits mostly of the middle class, at work and play indoors. Rubens’ portrait of himself and his first wife (1609) in their wedding attire is a virtuoso example of the couple portrait.[55] Rubens fame extended beyond his art—he was a courtier, diplomat, art collector, and successful businessman. His studio was one of the most extensive of that time, employing specialists in still-life, landscape, animal and genre scenes, in addition to portraiture. Van Dyck trained there for two years.[56] Charles I of England first employed Rubens, then imported van Dyck as his court painter, knighting him and bestowing on him courtly status. Van Dyck not only adapted Rubens’ production methods and business skills, but also his elegant manners and appearance. As was recorded, "He always went magnificently dress’d, had a numerous and gallant equipage, and kept so noble a table in his apartment, that few princes were not more visited, or better serv’d."[57] In France, Hyacinthe Rigaud dominated in much the same way, as a remarkable chronicler of royalty, painting the portraits of five French kings.[58]

One of the innovations of Renaissance art was the improved rendering of facial expressions to accompany different emotions. In particular, Dutch painter Rembrandt explored the many expressions of the human face, especially as one of the premier self-portraitists (of which he painted over 60 in his lifetime).[59] This interest in the human face also fostered the creation of the first caricatures, credited to the Accademia degli Incamminati, run by painters of the Carracci family in the late 16th century in Bologna, Italy.

Group portraits were produced in great numbers during the Baroque period, particularly in the Netherlands. Unlike in the rest of Europe, Dutch artists received no commissions from the Calvinist Church which had forbidden such images or from the aristocracy which was virtually non-existent. Instead, commissions came from civic and businesses associations. Dutch painter Frans Hals used fluid brush strokes of vivid color to enliven his group portraits, including those of the civil guards to which he belonged. Rembrandt benefitted greatly from such commissions and from the general appreciation of art by bourgeois clients, who supported portraiture as well as still-life and landscapes painting. In addition, the first significant art and dealer markets flourished in Holland at that time.[60]

With plenty of demand, Rembrandt was able to experiment with unconventional composition and technique, such as chiaroscuro. He demonstrated these innovations, pioneered by Italian masters such as Caravaggio, most notably in his famous Night Watch (1642).[61] The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp (1632) is another fine example of Rembrandt's mastery of the group painting, in which he bathes the corpse in bright light to draw attention to the center of the painting while the clothing and background merge into black, making the faces of the surgeon and the students standout. It is also the first painting that Rembrandt signed with his full name.[62]

In Spain, Diego Velázquez painted Las Meninas (1656), one of the most famous and enigmatic group portraits of all time. It memorializes the artist and the children of the Spanish royal family, and apparently the sitters are the royal couple who are seen only as reflections in a mirror.[63] Starting out as primarily a genre painter, Velázquez quickly rose to prominence as the court painter of Philip IV, excelling in the art of portraiture, particularly in extending the complexity of group portraits.[64]

Rococo artists, who were particularly interested in rich and intricate ornamentation, were masters of the refined portrait. Their attention to the details of dress and texture increased the efficacy of portraits as testaments to worldly wealth, as evidenced by François Boucher's famous portraits of Madame de Pompadour attired in billowing silk gowns.

The first major native portrait painters of the British school were English painters Thomas Gainsborough and Sir Joshua Reynolds, who also specialized in clothing their subjects in an eye-catching manner. Gainsborough's Blue Boy is one of the most famous and recognized portraits of all time, painted with very long brushes and thin oil color to achieve the shimmering effect of the blue costume.[66] Gainsborough was also noted for his elaborate background settings for his subjects.

The two British artists had opposite opinions on using assistants. Reynolds employing them regularly (sometimes doing only 20 percent of the painting himself) while Gainsborough rarely did.[67] Sometimes a client would extract a pledge from the artist, as did Sir Richard Newdegate from portraitist Peter Lely (van Dyck's successor in England), who promised that the portrait would be "from the Beginning to ye end drawne with my owne hands."[68] Unlike the exactitude employed by the Flemish masters, Reynolds summed up his approach to portraiture by stating that, "the grace, and, we may add, the likeness, consists more in taking the general air, than in observing the exact similitude of every feature."[69] Also prominent in England was William Hogarth, who dared to buck conventional methods by introducing touches of humor in his portraits. His "Self-portrait with Pug" is clearly more a humorous take on his pet than a self-indulgent painting.[70]

In the 18th century, female painters gained new importance, particularly in the field of portraiture. Notable female artists include French painter Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, Italian pastel artist Rosalba Carriera, and Swiss artist Angelica Kauffman. Also during that century, before the invention of photography, miniature portraits―painted with incredible precision and often encased in gold or enameled lockets―were highly valued.

In the United States, John Singleton Copley, schooled in the refined British manner, became the leading painter of full-size and miniature portraits, with his hyper-realistic pictures of Samuel Adams and Paul Revere especially well-regarded. Copley is also notable for his efforts to merge portraiture with the academically more revered art of history painting, which he attempted with his group portraits of famous military men.[71] Equally famous was Gilbert Stuart who painted over 1,000 portraits and was especially known for his presidential portraiture. Stuart painted over 100 replicas of George Washington alone.[72] Stuart worked quickly and employed softer, less detailed brush strokes than Copley to capture the essence of his subjects. Sometimes he would make several versions for a client, allowing the sitter to pick their favorite.[73] Noted for his rosy cheek tones, Stuart wrote, "flesh is like no other substance under heaven. It has all the gaiety of the silk-mercer's shop without its gaudiness of gloss, and all the softness of old mahogany, without its sadness." [74] Other prominent American portraitists of the colonial era were John Smibert, Thomas Sully, Ralph Earl, John Trumbull, Benjamin West, Robert Feke, James Peale, Charles Willson Peale, and Rembrandt Peale.

Sir Kenelm Digby by Anthony Van Dyck, c. 1640

Sir Kenelm Digby by Anthony Van Dyck, c. 1640 Rembrandt van Rijn, Portrait of Jan Six, 1654

Rembrandt van Rijn, Portrait of Jan Six, 1654

%2C_by_Pompeo_Batoni.jpg) Thomas Kerrich (1748-1828), by Pompeo Batoni

Thomas Kerrich (1748-1828), by Pompeo Batoni John Durand, The Rapalje Children, 1768, New-York Historical Society, New York City

John Durand, The Rapalje Children, 1768, New-York Historical Society, New York City John Singleton Copley, Paul Revere, 1770

John Singleton Copley, Paul Revere, 1770

19th century

In the late 18th century and early 19th century, neoclassical artists continued the tradition of depicting subjects in the latest fashions, which for women by then, meant diaphanous gowns derived from ancient Greek and Roman clothing styles. The artists used directed light to define texture and the simple roundness of faces and limbs. French painters Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres demonstrated virtuosity in this draftsman-like technique as well as a keen eye for character. Ingres, a student of David, is notable for his portraits in which a mirror is painted behind the subject to simulate a rear view of the subject.[75] His portrait of Napoleon on his imperial throne is a tour de force of regal portraiture. (see Gallery below)

Romantic artists who worked during the first half of the 19th century painted portraits of inspiring leaders, beautiful women, and agitated subjects, using lively brush strokes and dramatic, sometimes moody, lighting. French artists Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault painted particularly fine portraits of this type, especially dashing horsemen.[76] A notable example of artist of romantic period in Poland, who practised a horserider portrait was Piotr Michałowski (1800–1855). Also noteworthy is Géricault's series of portraits of mental patients (1822–1824). Spanish painter Francisco de Goya painted some of the most searching and provocative images of the period, including La maja desnuda (c. 1797–1800), as well as famous court portraits of Charles IV.

The realist artists of the 19th century, such as Gustave Courbet, created objective portraits depicting lower and middle-class people. Demonstrating his romanticism, Courbet painted several self-portraits showing himself in varying moods and expressions.[77] Other French realists include Honoré Daumier who produced many caricatures of his contemporaries. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec chronicled some of the famous performers of the theater, including Jane Avril, capturing them in motion.[78] French painter Édouard Manet, was an important transitional artist whose work hovers between realism and impressionism. He was a portraitist of outstanding insight and technique, with his painting of Stéphane Mallarmé being a good example of his transitional style. His contemporary Edgar Degas was primarily a realist and his painting Portrait of the Bellelli Family is an insightful rendering of an unhappy family and one of his finest portraits.[79]

In America, Thomas Eakins reigned as the premier portrait painter, taking realism to a new level of frankness, especially with his two portraits of surgeons at work, as well as those of athletes and musicians in action. In many portraits, such as "Portrait of Mrs. Edith Mahon", Eakins boldly conveys the unflattering emotions of sorrow and melancholy.[80]

The Realists mostly gave way to the Impressionists by the 1870s. Partly due to their meager incomes, many of the Impressionists relied on family and friends to model for them, and they painted intimate groups and single figures in either outdoors or in light-filled interiors. Noted for their shimmering surfaces and rich dabs of paint, Impressionist portraits are often disarmingly intimate and appealing. French painters Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir created some of the most popular images of individual sitters and groups. American artist Mary Cassatt, who trained and worked in France, is popular even today for her engaging paintings of mothers and children, as is Renoir.[81] Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh, both Post-Impressionists, painted revealing portraits of people they knew, swirling in color but not necessarily flattering. They are equally, if not more so, celebrated for their powerful self-portraits.

John Singer Sargent also spanned the change of century, but he rejected overt Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. He was the most successful portrait painter of his era, using a mostly realistic technique often effused with the brilliant use of color. He was equally apt at individual and group portraits, particularly of upper-class families. Sargent was born in Florence, Italy to American parents. He studied in Italy and Germany, and in Paris. Sargent is considered to be the last major exponent of the British portrait tradition beginning with van Dyck.[81] Another prominent American portraitist who trained abroad was William Merritt Chase. American society painter Cecilia Beaux, called the "female Sargent", was born of a French father, studied abroad and gained success back home, sticking with traditional methods. Another portraitist compared to Sargent for his lush technique was Italian-born Parisian artist Giovanni Boldini, a friend of Degas and Whistler.

American-born Internationalist James Abbott McNeill Whistler was well-connected with European artists and also painted some exceptional portraits, most famously his Arrangement in Grey and Black, The Artist's Mother (1871), also known as Whistler's Mother.[82] Even with his portraits, as with his tonal landscapes, Whistler wanted his viewers to focus on the harmonic arrangement of form and color in his paintings. Whistler used a subdued palette to create his intended effects, stressing color balance and soft tones. As he stated, "as music is the poetry of sound, so is painting the poetry of sight, and the subject-matter has nothing to do with the harmony of sound or of color."[83] Form and color were also central to Cézanne's portraits, while even more extreme color and brush stroke technique dominate the portraits by André Derain, and Henri Matisse.[84]

The development of photography in the 19th century had a significant effect on portraiture, supplanting the earlier camera obscura which had also been previously used as an aid in painting. Many modernists flocked to the photography studios to have their portraits made, including Baudelaire who, though he proclaimed photography an "enemy of art", found himself attracted to photography's frankness and power.[85] By providing a cheap alternative, photography supplanted much of the lowest level of portrait painting. Some realist artists, such as Thomas Eakins and Edgar Degas, were enthusiastic about camera photography and found it to be a useful aid to composition. From the Impressionists forward, portrait painters found a myriad number of ways to reinterpret the portrait to compete effectively with photography.[86] Sargent and Whistler were among those stimulated to expand their technique to create effects that the camera could not capture.

Francisco de Goya, Charles IV of Spain and His Family, 1800–1801

Francisco de Goya, Charles IV of Spain and His Family, 1800–1801 Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, portrait of Napoleon on his Imperial Throne, 1806, Musée de l'Armée, Paris

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, portrait of Napoleon on his Imperial Throne, 1806, Musée de l'Armée, Paris

Gustave Courbet, Portrait of Charles Baudelaire, 1848

Gustave Courbet, Portrait of Charles Baudelaire, 1848 Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait of Alfred Sisley, 1868

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait of Alfred Sisley, 1868 James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Arrangement in Grey and Black: The Artist's Mother (1871) popularly known as Whistler's Mother

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Arrangement in Grey and Black: The Artist's Mother (1871) popularly known as Whistler's Mother Edgar Degas, Portrait of Miss Cassatt, Seated, Holding Cards, 1876-1878

Edgar Degas, Portrait of Miss Cassatt, Seated, Holding Cards, 1876-1878 John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson, 1887

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson, 1887

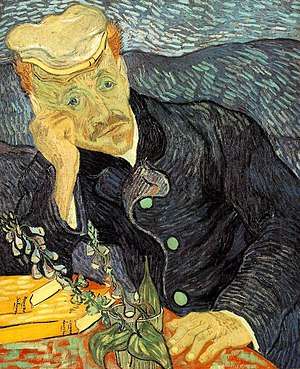

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of Doctor Gachet, (first version), 1890

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of Doctor Gachet, (first version), 1890

20th century

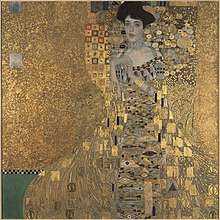

Other early 20th-century artists also expanded the repertoire of portraiture in new directions. Fauvist artist Henri Matisse produced powerful portraits using non-naturalistic, even garish, colors for skin tones. Cézanne's relied on highly simplified forms in his portraits, avoiding detail while emphasizing color juxtapositions.[88] Austrian Gustav Klimt's unique style applied Byzantine motifs and gold paint to his memorable portraits. His pupil Oskar Kokoschka was an important portraitist of the Viennese upper class. Prolific Spanish artist Pablo Picasso painted many portraits, including several cubist renderings of his mistresses, in which the likeness of the subject is grossly distorted to achieve an emotional statement well beyond the bounds of normal caricature.[89] An outstanding female portrait painter of the turn of the 20th century, associated with the French impressionism, was Olga Boznańska (1865–1940). Expressionist painters provided some of the most haunting and compelling psychological studies ever produced. German artists such as Otto Dix and Max Beckmann produced notable examples of expressionist portraiture. Beckmann was a prolific self-portraitist, producing at least twenty-seven.[90] Amedeo Modigliani painted many portraits in his elongated style which depreciated the "inner person" in favor of strict studies of form and color. To help achieve this, he de-emphasized the normally expressive eyes and eyebrows to the point of blackened slits and simple arches.[91]

British art was represented by the Vorticists, who painted some notable portraits in the early part of the 20th century. The Dada painter Francis Picabia executed numerous portraits in his unique fashion. Additionally, Tamara de Lempicka's portraits successfully captured the Art Deco era with her streamlined curves, rich colors and sharp angles. In America, Robert Henri and George Bellows were fine portraitists of the 1920s and 1930s of the American realist school. Max Ernst produced an example of a modern collegial portrait with his 1922 painting All Friends Together.[92]

A significant contribution to the development of portrait painting of 1930–2000 was made by Russian artists, mainly working in the traditions of realist and figurative painting. Among them should be called Isaak Brodsky, Nikolai Fechin, Abram Arkhipov and others.[93]

Portrait production in Europe (excluding Russia) and the Americas generally declined in the 1940s and 1950s, a result of the increasing interest in abstraction and nonfigurative art. One exception, however, was Andrew Wyeth who developed into the leading American realist portrait painter. With Wyeth, realism, though overt, is secondary to the tonal qualities and mood of his paintings. This is aptly demonstrated with his landmark series of paintings known as the "Helga" pictures, the largest group of portraits of a single person by any major artist (247 studies of his neighbor Helga Testorf, clothed and nude, in varying surroundings, painted during the period 1971–1985).[94]

By the 1960s and 1970s, there was a revival of portraiture. English artists such as Lucian Freud (grandson of Sigmund Freud) and Francis Bacon have produced powerful paintings. Bacon's portraits are notable for their nightmarish quality. In May 2008, Freud's 1995 portrait Benefits Supervisor Sleeping was sold by auction by Christie's in New York City for $33.6 million, setting a world record for sale value of a painting by a living artist.[95]

Many contemporary American artists, such as Andy Warhol, Alex Katz and Chuck Close, have made the human face a focal point of their work.

Warhol was one of the most prolific portrait painters in the 20th-century. Warhol's painting Orange Shot Marilyn of Marilyn Monroe is an iconic early example off his work from the 1960s, and Orange Prince (1984) of the pop singer Prince is later example, both exhibiting Warhol's unique graphic style of portraiture.[96][97][98][99]

Close's specialty was huge, hyper-realistic wall-sized "head" portraits based on photographic images. Jamie Wyeth continues in the realist tradition of his father Andrew, producing famous portraits whose subjects range from Presidents to pigs.

Henri Matisse, The Green Stripe, Portrait of Madame Matisse, 1905

Henri Matisse, The Green Stripe, Portrait of Madame Matisse, 1905 Olga Boznańska, Self-portrait, 1906, National Museum in Warsaw

Olga Boznańska, Self-portrait, 1906, National Museum in Warsaw Umberto Boccioni, Self-portrait, 1906

Umberto Boccioni, Self-portrait, 1906

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, 1910, The Art Institute of Chicago

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, 1910, The Art Institute of Chicago Juan Gris, Portrait of Pablo Picasso, 1912

Juan Gris, Portrait of Pablo Picasso, 1912.jpg) Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Chaim Soutine, 1916

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Chaim Soutine, 1916 Boris Grigoriev, Portrait of Vsevolod Meyerhold, 1916

Boris Grigoriev, Portrait of Vsevolod Meyerhold, 1916

Islamic world and South Asia

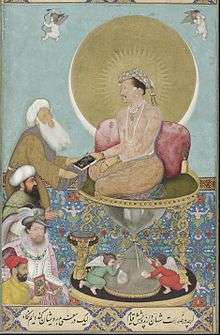

The Persian miniature tradition avoided giving figures individualized facial features for a long time, partly for religious reasons, to avoid any hint of idolatry. Rulers in the Islamic world never put their images on their coins, and their appearance did not form part of their public relations effort in the way that it did in the West. Even where it is clear that a scene shows the court of the prince commissioning the work, the features of the chief figure have the same rather Chinese-looking features as all the rest. This long-lasting convention seems to derive from the start of the miniature tradition under the Mongol Ilkhanids, but long outlived them.

When the Persian tradition developed as the Mughal miniature in India, things rapidly changed. Unlike their Persian predecessors, Mughal patrons placed great emphasis on detailed naturalistic likenesses of all the unfamiliar natural forms of their new empire, such as animals, birds and plants. They had the same attitude to human portraiture, and individual portraits, normally in profile, became an important feature of the tradition. This received a particular emphasis under Emperor Akbar the Great, who seems to have been dyslexic, and could barely read or write himself. He had a large album (muraqqa) made with portraits of all the leading members of his huge court, and used this when considering appointments around the empire with his advisors.[100]

Later emperors, especially Jahangir and Shah Jahan, made great use of idealized miniature portraits of themselves as a form of propaganda, distributing them to significant allies. These often featured halos larger than those given to any religious figures. Such images spread the idea of the portrait of the ruler to smaller courts, so that by the 18th century many small rajahs maintained court artists to portray them enjoying princely activities in rather stylized images that combine senses of informality and majesty.

Ottoman miniatures generally had figures with faces even less individualized than its Persian equivalents, but a genre of small portraits of males from the Imperial family developed. These had highly individual, and rather exaggerated, features, some verging on caricatures; they were probably seen only by a very restricted circle.

The Persian Qajar dynasty, from 1781, took to large royal portraits in oils, as well as miniatures and textile hangings. These tend to be dominated by the magnificent costumes and long beards of the shahs.

Chinese portrait painting

Chinese portrait painting was slow to desire or achieve an actual likeness. Many "portraits" were of famous figures from the past, and showed an idea of what that person should look like. Buddhist clergy, especially in sculpture, were something of an exception to this. Portraits of the emperor were long never seen in public, partly for fear that mistreatment of them might dishonour the emperor or even cause bad luck. The most senior ministers were allowed once a year to pay homage to the images in the imperial gallery of ancestor portraits, as a special honour.

Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD)

During the Han dynasty, the rise of Confucianism, which regarded human as the center of the universe and society, led to a focus on psychological study. In the meantime, Taoist scholars started the study of physiognomy. The combined interests in human psychological and physical features caused a growth in biography and portraiture. Portrait paintings created during the Han dynasty were considered prototypes of the earliest Chinese portrait paintings, most of which were found on the walls of palace halls, tomb chambers, and offering shrines. For instance, the engraved figure of a man found in a tomb tile from western Henan dating back to the third century B.C. indicates the painter's observation and desire to create lively figures. However, the subjects of most wall portraits are anonymous figures engaging in conversation. Despite the vivid depiction of physical features and facial expression, due to the lack of identity and the close bound to narrative context, many scholars categorize these Han dynasty wall paintings as “character figures in action” instead of actual likenesses of specific individuals.[101]

Jin dynasty (265-410 AD)

The Jin dynasty was one of the most turbulent periods in ancient Chinese history. After the decades of wars between the three states of Wei, Shu, and Wu from 184 to 280 AD, Sima Yan eventually founded the Western Jin dynasty in 266 AD. The unstable socio-political environment and the declining imperial authority resulted in a transition from Confucianism to Neo-Daoism. As the attitude of breaking social hierarchy and decorum flourished, self-expression and individualism started to grow among the intelligentsia.

The Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove and Rong Qiqi is a thread-relief painting on tile found in a Jin dynasty brick-chambered tomb in Nanjing. The relief is 96 inches in length and 35 inches in width, with more than 300 bricks. It is one of the most well-preserved thread-relief paintings from the Jin dynasty which reflect high-quality craftsmanship. There are two parts of the relief and each contains four figure portraits. According to the names inscribed next to the figures, from the top to the bottom, and from the left to the right, the eight figures are Rong Qiqi, Ruan Xian, Liu Ling, Xiang Xiu, Ji Kang, Ruan Ji, Shan Tao, and Wang Rong. Other than Rong Qiqi, the other seven people were famous Neo-Daoist scholars of the Jin dynasty and were known as the "Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove". They were eminent intelligentsias accomplished at literature, music, or philosophy. The relief depicts a narrative scene of the eight cultivated gentlemen sitting on the ground in the grove performing various activities. The figures were portrayed in a relaxed and self-absorbed posture wearing loose garments with bare feet.

The historically-recorded name inscriptions next to the figures cause the relief painting functions as “portraiture represents specific people”.[102] In addition, the iconographic details of each figure based on biography renders an extent of individualization. For instance, the biography of Liu Ling in the Book of Jin records his obsession with alcohol. In the relief paining, the figure of Liu Ling sits in a casual posture with a curving knee and holds an erbei, a vessel for alcohol, while dipping the other hand into the cup to have a taste of the drink. The portrait reflects the essence of Liu Ling's characteristics and temperament. The figure of Ruan Xian who was famous for musical talents according to the Book of Jin plays a flute in the portrait.

Gu Kaizhi, one of the most famous artists of the Eastern Jin dynasty, instructed how to reflect the sitter's characteristics through accurate portray of the physical features in his book On Painting. He also stressed the capture of the sitter's spirit through vivid depiction of eyes.[101]

Tang dynasty (618–907)

During the Tang dynasty, there was an increase of humanization and personalization in portrait painting. Due to the influx of Buddhism, the painting portrait adopted a more realistic likeness, especially for the portraits of the monks. The belief in “temporal incorruptibility” of the immortal body in Mahayana Buddhism linked the presence in an image with the presence in reality. Portrait was regarded as the visual embodiment and substitute of a real person. Thus, the true likeness was highly valued in the paintings and statues of the monks.[101] The Tang dynasty mural portrait painting values the spiritual quality—the “animation through spirit consonance” (qi yun shen tong).[103]

In terms of the imperial portrait, Emperor Taizong, the second emperor of the Tang dynasty, used portraits to legitimize succession and reinforce power. He commissioned the Portrait of Succession Emperors, which contains the portraits of 13 emperors in the previous dynasties in chronological order. The commonness among the selected emperors was that they were the sons of the founders of the dynasties. Since Emperor Taizong's father, Emperor Gaozu, was the founder of the Tang dynasty, Emperor Taizong's selection of the previous emperors in the similar position of himself served as a political allusion. His succession was under doubt and criticism since he murdered two of his brothers and forced his father to pass the throne to him. Through commissioning the collective portraits of the previous emperors, he aimed at legitimize the transmission of the reign. In addition, the difference in the costumes of the portrayed emperors implied Emperor Taizong's opinion on them. The emperors portrayed in informal costumes were regarded as the bad examples of a ruler such as being weak or violent, while the ones in formal dresses were thought to accomplish either civil or military achievements. The commission was an indirect method by Emperor Taizong to proclaim his achievements had surpassed the precedent emperors. Emperor Taizong also commissioned a series of portrait paintings of famous scholars and intellectuals before he became the emperor. He attempted to befriend with the intellectuals by putting the portraits on the wall of Pingyan Pavilion as a signal of respect. The portraits also served as evidence that he had gained political support from the portrayed famous scholars to frighten his opponents. During his reign, Emperor Taizong commissioned portraits of himself receiving offerings from the ambassadors of the conquered foreign countries to celebrate and advertise his military achievements.[104]

Song dynasty (960–1279)

During the Song dynasty, Emperor Gaozong commissioned Portraits of Confucius and Seventy-two Disciples (sheng xian tu) on blank ground with his handwritten inscription. The figures were portrayed in vivid lines, animated gestures, and the facial expressions were rendered a narrative quality. The portrait of the saints and his disciples was found on a stone tablet on the wall of Imperial University as a moral code to educate the students. However, scholars argued that Emperor Gaozong's true purpose of the commission was to announce that his policies were supported by Confucianism as well as his control over the Confucian heritage.[105]

Yuan dynasty (1271-1368)

The Yuan dynasty was a watershed moment in Chinese history. After the Mongol Empire conquered the Chinese mainland and ended the Song dynasty, the traditional Chinese intelligentsia were left in a dilemma situation of choosing between reclusion from the foreign government or pursuing new political careers. Portrait paintings of “men of culture” (wen ren hua) at that period reflects this dilemma. For instance, the Portrait of Yang Qian depicted him standing in a bamboo forest. While the bamboo symbolizes his moral rightness, the half-enclosed and half-opened space in the background alludes to his potential of choosing between reclusion and serve in the Mongol government.[106]

In terms of imperial portrait, the Portrait of Kublai and the Portrait of Chabi by Mongol imperial painter Araniko in 1294 reflect the fusion of the traditional Chinese imperial portrait techniques and the Himalayan-Mongol aesthetic value. Kublai Khan was portrayed as an elder man while Empress Chabi was depicted in youth, both wearing traditional Mongolian imperial costumes. Araniko adopted the Chinese portrait technique such as outlining the shape with ink and reinforcing the shape with color, whereas the highlights on Chabi's jewelry with the same hue but lighter value proved to be a continuation of the Himalayan style. The full frontal orientation of the sitters and their centered pupil add a confrontational impact to the viewer, which reflect the Nepali aesthetics and style. The highly symmetrical composition and the rigid depiction of hair and clothes differed from the previous Song dynasty painting style. There is little implication on the moral merit of the sitters or their personality, indicating a detachment of the painter from the sitter, which contradicts with the Song dynasty's emphasis on the capture of the spirit.[107]

Qing dynasty (1636-1912)

During the Qing dynasty, the eighteenth century European masquerade court portraiture which portrayed the aristocrats engaging in various activities in different costumes was imported to China. The Yongzheng Emperor and his son, the Qianlong Emperor, commissioned a number of masquerade portrait paintings with various political implications. In most of the Yongzheng Emperor's masquerade portrait, he wears exotic costumes such as the suit of the European gentleman. The lack of inscription on the portrait painting leaves his intention unclear, but some scholars believe the exotic costume reflects his interest in foreign culture and desire to rule the world. Compared with the Yongzheng Emperor's ambiguous attitude, the Qianlong Emperor wrote inscriptions on his masquerade portraits to announce his philosophy of the “Way of Ruling” which was to conceal and to deceive so that his subordinates and enemies cannot trace his strategies. Compared with the Yongzheng Emperor's enthusiasm in exotic costume, the Qianlong Emperor showed more interest in Chinese traditional costume such as dressing as a Confucian scholar, Taoist priest, and Buddhist monk, which manifests his desire in conquer the traditional Chinese heritage.

The Qianlong Emperor commissioned the Spring’s Peaceful Message after he inherited the throne from his father, which is a double portrait painting of him and his father dressed in Confucian scholar garments instead of traditional Manchu robes standing side by side next to bamboos. Scholars believe that the commission aimed to legitimize his succession of the throne by emphasizing the physical similarity between him and his father such as facial structure, identical costume and hairstyle. The bamboo forest in the background indicate their moral righteousness proposed by traditional Confucianism. The portrait depicts the Yongzheng Emperor, who is in a larger scale, handing a flowering branch to the Qianlong Emperor as a political metaphor of the imperial authority to reign. The Qianlong Emperor also advertised his filial piety proposed by Confucianism by posing in a modest gesture.[108]

The Jesuit painter Giuseppe Castiglione spent 50 years at the imperial court before his death in 1766, and was a court painter to three emperors. In his portraits, as with other genres, he combined aspects of Chinese traditional style with contemporary Western painting.

Portrait painting of women from the Han dynasty to Qing dynasty

Portrait painting of women in ancient China from the Han dynasty to the Qing dynasty (206 BC – 1912) developed under great impact of the Confucian patriarchal cosmology, however, the subject and the style varied according to the culture of each dynasty.

In the Han dynasty (206 BC - 220 AD), women in the portrait painting were mainly a type rather than specific individual. The major subject was idealized exemplary women (lie nü) with virtues prompted by Confucianism such as chastity, three-fold obedience (san cong) to father, husband, son. Gu Kaizhi’s handscroll Exemplary Women (lie nü tu) which was created shortly after the Han dynasty represents this genre.

In the Tang dynasty (618–906), palace women (shi nü) performing daily chores or entertainment became a popular subject. The feminine beauty and charm of the palace ladies were valued, but the subject remained nonspecific under the painting name “Palace Ladies”. Characteristics encouraged by the Confucianism including submissive and agreeable were encompassed as standards of beauty and emphasized in the portrait. Painters pursued correctness and likeness of the sitter and aimed to reveal the purity of the soul.

In the Song dynasty (960–1279), portrait paintings of women were created based on love poems written by court poets. Although depicted as living in luxurious fashion and comfortable housing, women in the painting were usually portrayed as lonely and melancholic because they feel deserted or trapped in the domestic chores while their husbands stayed outside and pursued their careers. Common settings include empty garden path and empty platform couch which hint the absence of male figures. Common background include flowering trees which were associated with beauty and banana trees which symbolized vulnerability of women.

In the Ming dynasty(1368–1644), literati painting (wenren hua) which combined painting, calligraphy, and poetry became a popular trend among the elites. Most women in the literati painting were abstract figures serving as visual metaphor and remained nonentity. In the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), the literati painting gained more variety of brushstroke and use of bright color.[109]

Portrait of Ho Bun (何斌), a late Ming Dynasty Scholar-bureaucrat, late 16th century to early 17th century, Chinese

Portrait of Ho Bun (何斌), a late Ming Dynasty Scholar-bureaucrat, late 16th century to early 17th century, ChineseFrom_Bijin-ga_(Pictures_of_Beautiful_Women)%2C_published_by_Tsutaya_Juzaburo_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Three Beauties of the Present Day by Utamaro, 1793

Three Beauties of the Present Day by Utamaro, 1793

See also

References and notes

- References

- Gordon C. Aymar, The Art of Portrait Painting, Chilton Book Co., Philadelphia, 1967, p. 119

- Aymar, p. 94

- Aymar, p. 129

- Aymar, p. 93

- Edwards, Betty (2012). Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. Penguin. p. 292. ISBN 978-1-101-56180-5.

- Aymar, p. 283

- Aymar, p. 235

- Aymar, p. 280

- Aymar, p. 51

- Aymar, p. 72

- Robin Simon, The Portrait in Britain and America, G. K. Hall & Co., Boston, 1987, p. 131, ISBN 0-8161-8795-9

- Simon, p. 129

- Simon, p. 131

- Aymar, p. 262

- Simon, p. 98

- Simon, p. 107

- Aymar, p. 268, 271, 278

- Aymar, p. 264

- Aymar, p. 265

- Aymar, p. 5

- Cheney, Faxon, and Russo, Self-Portraits by Women Painters, Ashgate Publishing, Hants (England), 2000, p. 7, ISBN 1-85928-424-8

- John Hope-Hennessy, The Portrait in the Renaissance, Bollingen Foundation, New York, 1966, pp. 71–72

- Natural History XXXV:2 trans H. Rackham 1952. Loeb Classical Library

- Cheney, Faxon, and Russo, p. 20

- David Piper, The Illustrated Library of Art, Portland House, New York, 1986, p. 297, ISBN 0-517-62336-6

- Piper, p. 337

- "Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de' Benci, c. 1474/1478". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- John Hope-Hennessy, p. 209

- Simon, p. 80

- John Hope-Hennessy, p. 54, 63

- Piper, p. 301

- Piper, p. 363

- Aymar, p. 29

- Piper, p. 365

- Bonafoux, p. 35

- John Hope-Hennessy, pp. 124–126

- Piper, p. 318

- John Hope-Hennessy, p. 20

- John Hope-Hennessy, p. 227

- John Hope-Hennessy, p. 212

- "Mona Lisa – Heidelberger Fund klärt Identität (English: Mona Lisa – Heidelberger find clarifies identity)" (in German). University of Heidelberg. Archived from the original on 2008-12-06. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- "German experts crack the ID of 'Mona Lisa'". MSN. 2008-01-14. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- "Researchers Identify Model for Mona Lisa". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- John Hope-Hennessy, pp. 103–4

- Piper, p. 338

- Piper, p. 345

- Pascal Bonafoux, Portraits of the Artist: The Self-Portrait in Painting, Skira/Rizzoli, New York, 1985, p. 31, ISBN 0-8478-0586-7

- John Hope-Hennessy, p. 52

- Piper, p. 330

- John Hope-Hennessy, p. 279

- John Hope-Hennessy, p. 182

- John Hope-Hennessy, p. 154

- John Hope-Hennessy, p. 187

- Families in beeld - Frauke K. Laarmann, Families in beeld: De ontwikkeling van het Noord-Nederlandse familieportret in de eerste helft van de zeventiende eeuw. Hilversum, 2002, Verloren, ISBN 978-90-6550-186-8 Retrieved December 25, 2010

- Bonafoux, p. 40

- Piper, pp. 408–410

- Simon, p. 109

- Aymar, p. 162

- Aymar, p. 161

- Piper, p. 421

- Aymar, p. 218

- Piper, p. 424

- Bonafoux, p. 62

- Piper, p. 418

- L to R: Louis' aunt, Henriette-Marie; his brother, Philippe, duc d'Orléans; the Duke's daughter, Marie Louise d'Orléans, and wife, Henriette-Anne Stuart; the Queen-mother, Anne of Austria; three daughters of Gaston d'Orléans; Louis XIV; the Dauphin Louis; Queen Marie-Thérèse; la Grande Mademoiselle

- Piper, p. 460

- Simon, p. 13, 97

- Simon, p. 97

- Aymar, p. 62

- Simon, p. 92

- Simon, p. 19

- Aymar, p. 204

- Aymar, p. 263

- Aymar, p. 149

- Bonafoux, p. 99

- Piper, p. 542

- Bonafoux, p. 111

- Piper, p. 585

- Piper, p. 568

- Aymar, p. 88

- Piper, p. 589

- Piper, p. 561

- Aymar, p. 299

- Piper, p. 576

- Piper, p. 552

- Simon, p. 49

- "Portrait of Gertrude Stein". Metropolitan Museum. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- Piper, p. 582

- Aymar, p. 54

- Aymar, p. 188

- Piper, p. 646

- Bonafoux, p. 45

- Sergei V. Ivanov. Unknown Socialist Realism. The Leningrad School. – Saint Petersburg: NP-Print Edition, 2007. – 448 p. ISBN 5-901724-21-6, ISBN 978-5-901724-21-7.

- ’’An American Vision: Three Generations of Wyeth Art, Boston, 1987, Little Brown & Company, p. 123, ISBN 0-8212-1652-X

- "Freud work sets new world record". BBC News Online. 14 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- "Andy Warhol Portraits That Changed The World Forever". Widewalls. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- "Andy Warhol. Marilyn Monroe. 1967 | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- AnOther (2011-06-15). "Warhol and the Diva". AnOther. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- "The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts – Andy Warhol Biography". warholfoundation.org. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- Smart, Ellen S., "Akbar, Illiterate Geniu", pp. 103–104, in Kalādarśana: American Studies in the Art of India, Joanna Gottfried Williams (ed), 1981, BRILL, ISBN 9004064982, 9789004064980, google books

- Seckel, Dietrich (1993). "The Rise of Portraiture in Chinese Art". Artibus Asiae. 53 (1/2): 7–26. doi:10.2307/3250505. JSTOR 3250505.

- West, Shearer. (2004). Portraiture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780191518034. OCLC 319070279.

- Fong, Mary H. (1984). "Tang Tomb Murals Reviewed in the Light of Tang Texts on Painting". Artibus Asiae. 45 (1): 35–72. doi:10.2307/3249745. JSTOR 3249745.

- Qiang, Ning (2008). "Imperial Portraiture as Symbol of Political Legitimacy: A New Study of the "Portraits of Successive Emperors"". Ars Orientalis. 35: 96–128. ISSN 0571-1371. JSTOR 25481909.

- Murray, Julia K. (March 1992). "The Hangzhou Portraits of Confucius and Seventy-two Disciples (Sheng xian tu): Art in the Service of Politics". The Art Bulletin. 74 (1): 7–18. doi:10.2307/3045847. JSTOR 3045847.

- Sensabaugh, David AKE (2009). "Fashioning Identities in Yuan-Dynasty Painting: Images of the Men of Culture". Ars Orientalis. 37: 118–139. ISSN 0571-1371. JSTOR 29550011.

- Jing, Anning (1994). "The Portraits of Khubilai Khan and Chabi by Anige (1245–1306), a Nepali Artist at the Yuan Court". Artibus Asiae. 54 (1/2): 40–86. doi:10.2307/3250079. JSTOR 3250079.

- "Wu Hung. Emperor's Masquerade – 'Costume Portraits' of Yongzheng and Qianlong | Orientations". www.orientations.com.hk. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- Fong, Mary H. (21/1996). "Images of Women in Traditional Chinese Painting". Woman's Art Journal. 17 (1): 22–27. doi:10.2307/1358525. JSTOR 1358525. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

- Notes

- The New Age "Art Notes" column of 28 February 1918 is a closely reasoned analysis of the rationale and aesthetic of portraiture by B.H. Dias (pseudonym of Ezra Pound), an insightful frame of reference for viewing any portrait, ancient or modern.

Further reading

- Woodall, Joanna. Portraiture: Facing the Subject. Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1997.

- West. S. Portraiture (Oxford History of Art), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004

- Brilliant, R. Portraiture (Essays in Art and Culture), Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Portrait paintings. |

.jpg)

.jpg)