Digital media

Digital media is any media that are encoded in machine-readable formats. Digital media can be created, viewed, distributed, modified and preserved on digital electronics devices. Digital can be defined as any data represented with a series of digits, and Media refers to a method of broadcasting or communicating information together digital media refers to any information that is broadcast to us through a screen.[1] This includes text, audio, video, and graphics that is transmitted over the internet, for viewing on the internet.[2]

Digital media

Examples of digital media include software, digital images, digital video, video games, web pages and websites, social media, digital data and databases, digital audio such as MP3, electronic documents and electronic books. Digital media often contrasts with print media, such as printed books, newspapers and magazines, and other traditional or analog media, such as photographic film, audio tapes or video tapes.

Digital media has had a significantly broad and complex impact on society and culture. Combined with the Internet and personal computing, digital media has caused disruptive innovation in publishing, journalism, public relations, entertainment, education, commerce and politics. Digital media has also posed new challenges to copyright and intellectual property laws, fostering an open content movement in which content creators voluntarily give up some or all of their legal rights to their work. The ubiquity of digital media and its effects on society suggest that we are at the start of a new era in industrial history, called the Information Age, perhaps leading to a paperless society in which all media are produced and consumed on computers.[3] However, challenges to a digital transition remain, including outdated copyright laws, censorship, the digital divide, and the spectre of a digital dark age, in which older media becomes inaccessible to new or upgraded information systems.[4] Digital media has a significant, wide-ranging and complex impact on society and culture.[3]

History

Codes and information by machines were first conceptualized by Charles Babbage in the early 1800s. Babbage imagined that these codes would give him instructions for his Motor of Difference and Analytical Engine, machines that Babbage had designed to solve the problem of error in calculations. Between 1822 and 1823, Ada Lovelace, mathematics, wrote the first instructions for calculating numbers on Babbage engines. Lovelace's instructions are now believed to be the first computer program. Although the machines were designed to perform analysis tasks, Lovelace anticipated the possible social impact of computers and programming, writing. "For in the distribution and combination of truths and formulas of analysis, which may become easier and more quickly subjected to the mechanical combinations of the engine, the relationships and the nature of many subjects in which science necessarily relates in new subjects, and more deeply researched […] there are in all extensions of human power or additions to human knowledge, various collateral influences, in addition to the primary and primary object reached." Other old machine readable media include instructions for pianolas and weaving machines.

It is estimated that in the year 1986 less than 1% of the world's media storage capacity was digital and in 2007 it was already 94%.[5] The year 2002 is assumed to be the year when human kind was able to store more information in digital than in analog media (the "beginning of the digital age").[6]

Digital computers

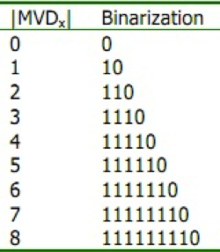

Though they used machine-readable media, Babbage's engines, player pianos, jacquard looms and many other early calculating machines were themselves analog computers, with physical, mechanical parts. The first truly digital media came into existence with the rise of digital computers.[7] Digital computers use binary code and Boolean logic to store and process information, allowing one machine in one configuration to perform many different tasks. The first modern, programmable, digital computers, the Manchester Mark 1 and the EDSAC, were independently invented between 1948 and 1949.[7][8] Though different in many ways from modern computers, these machines had digital software controlling their logical operations. They were encoded in binary, a system of ones and zeroes that are combined to make hundreds of characters. The 1s and 0s of binary are the "digits" of digital media.[9]

In 1959, the metal–oxide–silicon field-effect transistor (MOSFET, or MOS transistor) was invented by Mohamed Atalla and Dawon Kahng at Bell Labs.[10][11] It was the first truly compact transistor that could be miniaturised and mass-produced for a wide range of uses.[12] The MOSFET led to the development of microprocessors, memory chips, and digital telecommunication circuits.[13] This led to the development of the personal computer (PC) in the 1970s, and the beginning of the microcomputer revolution[14] and the Digital Revolution.[15][16][17][18]

"As We May Think"

While digital media did not come into common use until the late 20th century, the conceptual foundation of digital media is traced to the work of scientist and engineer Vannevar Bush and his celebrated essay "As We May Think," published in The Atlantic Monthly in 1945.[19] Bush envisioned a system of devices that could be used to help scientists, doctors, historians and others, store, analyze and communicate information.[19] Calling this then-imaginary device a "memex", Bush wrote:

The owner of the memex, let us say, is interested in the origin and properties of the bow and arrow. Specifically he is studying why the short Turkish bow was apparently superior to the English long bow in the skirmishes of the Crusades. He has dozens of possibly pertinent books and articles in his memex. First he runs through an encyclopedia, finds an interesting but sketchy article, leaves it projected. Next, in a history, he finds another pertinent item, and ties the two together. Thus he goes, building a trail of many items. Occasionally he inserts a comment of his own, either linking it into the main trail or joining it by a side trail to a particular item. When it becomes evident that the elastic properties of available materials had a great deal to do with the bow, he branches off on a side trail which takes him through textbooks on elasticity and tables of physical constants. He inserts a page of longhand analysis of his own. Thus he builds a trail of his interest through the maze of materials available to him.[20]

Bush hoped that the creation of this memex would be the work of scientists after World War II.[20] Though the essay predated digital computers by several years, "As We May Think," anticipated the potential social and intellectual benefits of digital media and provided the conceptual framework for digital scholarship, the World Wide Web, wikis and even social media.[19][21] It was recognized as a significant work even at the time of its publication.[20]

Digital multimedia

Practical digital multimedia distribution and streaming was made possible by advances in data compression, due to the impractically high memory, storage and bandwidth requirements of uncompressed media.[22] The most important compression technique is the discrete cosine transform (DCT),[23] a lossy compression algorithm that was first proposed as an image compression technique by Nasir Ahmed at the University of Texas in 1972.[24] The DCT algorithm was the basis for the first practical video coding format, H.261, in 1988.[25] It was followed by more DCT-based video coding standards, most notably the MPEG video formats from 1991 onwards.[23] The JPEG image format, also based on the DCT algorithm, was introduced in 1992.[26] The development of the modified discrete cosine transform (MDCT) algorithm led to the MP3 audio coding format in 1994,[27] and the Advanced Audio Coding (AAC) format in 1999.[28]

Impact

The digital revolution

Since the 1960s, computing power and storage capacity have increased exponentially, largely as a result of MOSFET scaling which enables MOS transistor counts to increase at a rapid pace predicted by Moore's law.[29][30][31] Personal computers and smartphones put the ability to access, modify, store and share digital media in the hands of billions of people. Many electronic devices, from digital cameras to drones have the ability to create, transmit and view digital media. Combined with the World Wide Web and the Internet, digital media has transformed 21st century society in a way that is frequently compared to the cultural, economic and social impact of the printing press.[3][32] The change has been so rapid and so widespread that it has launched an economic transition from an industrial economy to an information-based economy, creating a new period in human history known as the Information Age or the digital revolution.[3]

The transition has created some uncertainty about definitions. Digital media, new media, multimedia, and similar terms all have a relationship to both the engineering innovations and cultural impact of digital media.[33] The blending of digital media with other media, and with cultural and social factors, is sometimes known as new media or "the new media."[34] Similarly, digital media seems to demand a new set of communications skills, called transliteracy, media literacy, or digital literacy.[35] These skills include not only the ability to read and write—traditional literacy—but the ability to navigate the Internet, evaluate sources, and create digital content.[36] The idea that we are moving toward a fully digital, paperless society is accompanied by the fear that we may soon—or currently—be facing a digital dark age, in which older media are no longer accessible on modern devices or using modern methods of scholarship.[4] Digital media has a significant, wide-ranging and complex effect on society and culture.[3]

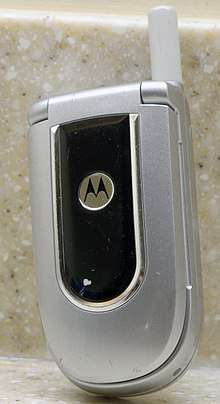

A senior engineer at Motorola named Martin Cooper was the first person to make a phone call on April 3, 1973. He decided the first phone call should be to a rival telecommunications company saying "I'm speaking via a mobile phone".[37] However the first commercial mobile phone was released in 1983 by Motorola. In the early 1990s Nokia came into succession, with their Nokia 1011 being the first mass-produced mobile phone.[37] The Nokia Communicator 9000 became the first smartphone as it was inputed with an Intel 24 MHz CPU and had a solid 8 MB of RAM. Smartphone users have increased by a lot over the years currently the highest countries with users include China with over 850 million users, India with over 350 million users, and in third place The United States with about 260 million users as of 2019.[38] While Android and iOS both dominate the smartphone market. A study By Gartner found that in 2016 about 88% of the worldwide smartphones were Android while iOS had a market share of about 12%.[39] About 85% of the mobile market revenue came from the mobile games.[39]

The impact of the digital revolution can also be assessed by exploring the amount of worldwide mobile smart device users there are. This can be split into 2 categories smart phone users and smart tablet users. Worldwide there are currently 2.32 billion smartphone users across the world.[40] This figure is to exceed 2.87 billion by 2020. Smart tablet users reached a total of 1 billion in 2015, 15% of the world's population.[41]

The statistics evidence the impact of digital media communications today. What is also of relevance is the fact that the numbers of smart device users is rising rapidly yet the amount of functional uses increase daily. A smartphone or tablet can be used for hundreds of daily needs. There are currently over 1 million apps on the Apple App store.[42] These are all opportunities for digital marketing efforts. A smartphone user is impacted with digital advertising every second they open their Apple or Android device. This further evidences the digital revolution and the impact of revolution. This has resulted in a total of 13 billion dollars being paid out to the various app developers over the years.[43] This growth has fueled the development of millions of software applications. Most of these apps are able to generate income via in app advertising.[39] Gross revenue for 2020 is projected to be about $189 million.[39]

Disruption in industry

Compared with print media, the mass media, and other analog technologies, digital media are easy to copy, store, share and modify. This quality of digital media has led to significant changes in many industries, especially journalism, publishing, education, entertainment, and the music business. The overall effect of these changes is so far-reaching that it is difficult to quantify. For example, in movie-making, the transition from analog film cameras to digital cameras is nearly complete. The transition has economic benefits to Hollywood, making distribution easier and making it possible to add high-quality digital effects to films.[44] At the same time, it has affected the analog special effects, stunt, and animation industries in Hollywood.[45] It has imposed painful costs on small movie theaters, some of which did not or will not survive the transition to digital.[46] The effect of digital media on other media industries is similarly sweeping and complex.[45]

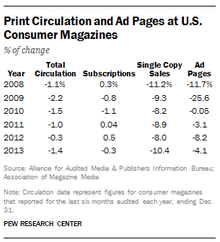

Between 2000–2015, the print newspaper advertising revenue has fallen from $60 billion to a nearly $20 billion.[47] Even one of the most popular days for papers, Sunday, has seen a 9% circulation decrease the lowest since 1945.[48]

In journalism, digital media and citizen journalism have led to the loss of thousands of jobs in print media and the bankruptcy of many major newspapers.[49] But the rise of digital journalism has also created thousands of new jobs and specializations.[50] E-books and self-publishing are changing the book industry, and digital textbooks and other media-inclusive curricula are changing primary and secondary education.[51][52]

In academia, digital media has led to a new form of scholarship, also called digital scholarship, making open access and open science possible thanks to the low cost of distribution. New fields of study have grown, such as digital humanities and digital history. It has changed the way libraries are used and their role in society.[32] Every major media, communications and academic endeavor is facing a period of transition and uncertainty related to digital media.

Often time the magazine or publisher have a Digital edition which can be referred to an electronic formatted version identical to the print version.[48] There is a huge benefit to the publisher here and its the cost, avoiding the expense to print and deliver brings an additional benefit for the company

Since 2004, there has been a decrease in newspaper industry employment, with only about 40,000 people working in the workforce currently.[53] Alliance of Audited Media & Publishers information during the 2008 recession, over 10% of print sales are diminished for certain magazines, with a hardship coming from only 75% of the sales advertisements as before.[48] However, in 2018, major newspapers advertising revenue was 35% from digital ads.[53]

In contrast, mobile versions of newspapers and magazines came in second with a huge growth of 135%. The New York Times has noted a 47% year of year rise in their digital subscriptions.[54] 43% of adults get news often from news websites or social media, compared with 49% for television. Pew Research also asked respondents if they got news from a streaming device on their TV – 9% of U.S. adults said that they do so often.[48]

Individual as content creator

Digital media has also allowed individuals to be much more active in content creation.[55] Anyone with access to computers and the Internet can participate in social media and contribute their own writing, art, videos, photography and commentary to the Internet, as well as conduct business online. The dramatic reduction in the costs required to create and share content have led to a democratization of content creation as well as the creation of new types of content, like blogs, memes and video essays. Some of these activities have also been labelled citizen journalism. This spike in user created content is due to the development of the internet as well as the way in which users interact with media today. The release of technologies such mobile devices allow for easier and quicker access to all things media.[56] Many media creation tools that were once available to only a few are now free and easy to use. The cost of devices that can access the Internet is steadily falling, and personal ownership of multiple digital devices is now becoming the standard. These elements have significantly affected political participation.[57] Digital media is seen by many scholars as having a role in Arab Spring, and crackdowns on the use of digital and social media by embattled governments are increasingly common.[58] Many governments restrict access to digital media in some way, either to prevent obscenity or in a broader form of political censorship.[59]

Over the years YouTube has grown to become a website with user generated media. This content is oftentimes not mediated by any company or agency, leading to a wide array of personalities and opinions online. Over the years YouTube and other platforms have also shown their monetary gains, as the top 10 YouTube performers generating over 10 million dollars each year. Many of these YouTube profiles over the years have a multi camera set up as we would see on TV. Many of these creators also creating their own digital companies as their personalities grow. Personal devices have also seen an increase over the years. Over 1.5 billion users of tablets exist in this world right now and that is expected to slowly grow [60] About 20% of people in the world regularly watch their content using tablets in 2018[60]

User-generated content raises issues of privacy, credibility, civility and compensation for cultural, intellectual and artistic contributions. The spread of digital media, and the wide range of literacy and communications skills necessary to use it effectively, have deepened the digital divide between those who have access to digital media and those who don't.[61]

The rising of digital media has made the consumer's audio collection more precise and personalized. It is no longer necessary to purchase an entire album if the consumer is ultimately interested in only a few audio files.

Web-only news

See also: Web television, streaming television.

_04.jpg)

The rise of streaming services has led to a decrease of cable TV services to about 59%, while streaming services are growing at around 29%, and 9% are still users of the digital antenna.[62] TV Controllers now incorporate designated buttons for streaming platforms.[63] Users are spending an average of 1:55 with digital video each day, and only 1:44 on social networks.[64] 6 out of 10 people report viewing their television shows and news via a streaming service.[62] Platforms such as Netflix have gained attraction due to their adorability, accessibility, and for its original content.[65] Companies such as Netflix have even bought previously cancelled shows such as Designated Survivor, Lucifer, and Arrested Development.[66] As the internet becomes more and more prevalent, more companies are beginning to distribute content through internet only means. With the loss of viewers, there is a loss of revenue but not as bad as what would be expected.

Copyright challenges

Digital media[67] pose several challenges to the current copyright and intellectual property laws.[68] The ease of creating, modifying and sharing digital media makes copyright enforcement a challenge, and copyright laws are widely seen as outdated.[69][70] For example, under current copyright law, common Internet memes are probably illegal to share in many countries.[71] Legal rights are at least unclear for many common Internet activities, such as posting a picture that belongs to someone else to a social media account, covering a popular song on a YouTube video, or writing fanfiction. Over the last decade the concept of fair use has been applied to many online medias.

Copyright challenges have gotten to all parts of digital media. Even as a personal content creator on YouTube, they must be careful and follow the guidelines set by copyright and IP laws. As YouTube creators very easily get demonetized for their content.[72] Oftentimes we see digital creators loose monetization in their content, get their contend deleted, or get criticized for their content. Most times this has to do with accidnelty using a copyrighted audio track or background scenes that are copyright by another company.[72]

To resolve some of these issues, content creators can voluntarily adopt open or copyleft licenses, giving up some of their legal rights, or they can release their work to the public domain. Among the most common open licenses are Creative Commons licenses and the GNU Free Documentation License, both of which are in use on Wikipedia. Open licenses are part of a broader open content movement that pushes for the reduction or removal of copyright restrictions from software, data and other digital media.[73] To facilitate the collection and consumption of such licensing information and availability status, tools have been developed like the Creative Commons Search engine (mostly for images on the web) and Unpaywall (for scholarly communication).

Additional software has been developed in order to restrict access to digital media. digital rights management (DRM) is used to lock material and allows users to use that media for specific cases. For example, DRM allows a movie producer to rent a movie at a lower price than selling the movie, restricting the movie rental license length, rather than only selling the movie at full price. Additionally, DRM can prevent unauthorized sharing or modification of media.

Digital Media is numerical, networked and interactive system of links and databases that allows us to navigate from one bit of content or webpage to another.

One form of digital media that is becoming a phenomenon is in the form of an online magazine or digital magazine. What exactly is a digital magazine? Due to the economic importance of digital magazines, the Audit Bureau of Circulations integrated the definition of this medium in its latest report (March 2011): a digital magazine involves the distribution of a magazine content by electronic means; it may be a replica.[74] This is an outdated definition of what a digital magazine is. A digital magazine should not be, in fact, a replica of the print magazine in PDF, as was common practice in recent years. It should, rather, be a magazine that is, in essence, interactive and created from scratch to a digital platform (Internet, mobile phones, private networks, iPad or other device).[74] The barriers for digital magazine distribution are thus decreasing. At the same time digitizing platforms are broadening the scope of where digital magazines can be published, such as within websites and on smartphones.[75] With the improvements of tablets and digital magazines are becoming visually enticing and readable magazines with it graphic arts.[76]

References

- Smith, Richard (2013-10-15). "What is Digital Media?". The Centre for Digital Media. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- Rayburn, Dan (2012-07-26). Streaming and Digital Media: Understanding the Business and Technology. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-03217-2.

- Dewar, James A. (1998). "The information age and the printing press: looking backward to see ahead". RAND Corporation. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Koehl, Sean (15 May 2013). "We need to act now to prevent a digital 'dark age'". Wired. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Hilbert, Martin; López, Priscila (2011). "The World's Technological Capacity to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information". Science. 332 (6025): 60–65. doi:10.1126/science.1200970. PMID 21310967. especially Supporting online material

- Martin Hilbert (11 June 2011). "World_info_capacity_animation" – via YouTube.

- Copeland, B. Jack (Fall 2008). "The modern history of computing". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- "Sci/tech pioneers recall computer creation". BBC. 15 April 1999. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "12 Projects You Should Know About Under the Digital India Initiative". 2 July 2015.

- "1960 - Metal Oxide Semiconductor (MOS) Transistor Demonstrated". The Silicon Engine. Computer History Museum.

- Lojek, Bo (2007). History of Semiconductor Engineering. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 321–3. ISBN 9783540342588.

- Moskowitz, Sanford L. (2016). Advanced Materials Innovation: Managing Global Technology in the 21st century. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 165–167. ISBN 9780470508923.

- Colinge, Jean-Pierre; Greer, James C. (2016). Nanowire Transistors: Physics of Devices and Materials in One Dimension. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9781107052406.

- Malmstadt, Howard V.; Enke, Christie G.; Crouch, Stanley R. (1994). Making the Right Connections: Microcomputers and Electronic Instrumentation. American Chemical Society. p. 389. ISBN 9780841228610.

The relative simplicity and low power requirements of MOSFETs have fostered today's microcomputer revolution.

- "The Foundation of Today's Digital World: The Triumph of the MOS Transistor". Computer History Museum. 13 July 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- Raymer, Michael G. (2009). The Silicon Web: Physics for the Internet Age. CRC Press. p. 365. ISBN 9781439803127.

- Wong, Kit Po (2009). Electrical Engineering - Volume II. EOLSS Publications. p. 7. ISBN 9781905839780.

- "Transistors - an overview". ScienceDirect. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- Simpson, Rosemary; Allen Renear; Elli Mylonas; Andries van Dam (March 1996). "50 years after "As We May Think": the Brown/MIT Vannevar Bush symposium" (PDF). Interactions. pp. 47–67. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Bush, Vannevar (1 July 1945). "As We May Think". The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Mynatt, Elizabeth. "As we may think: the legacy of computing research and the power of human cognition". Computing Research Association. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Lee, Jack (2005). Scalable Continuous Media Streaming Systems: Architecture, Design, Analysis and Implementation. John Wiley & Sons. p. 25. ISBN 9780470857649.

- Ce, Zhu (2010). Streaming Media Architectures, Techniques, and Applications: Recent Advances: Recent Advances. IGI Global. p. 26. ISBN 9781616928339.

- Ahmed, Nasir (January 1991). "How I came up with the discrete cosine transform". Digital Signal Processing. 1 (1): 4–5. doi:10.1016/1051-2004(91)90086-Z.

- Ghanbari, Mohammed (2003). Standard Codecs: Image Compression to Advanced Video Coding. Institution of Engineering and Technology. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9780852967102.

- "T.81 – DIGITAL COMPRESSION AND CODING OF CONTINUOUS-TONE STILL IMAGES – REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDELINES" (PDF). CCITT. September 1992. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- Guckert, John (Spring 2012). "The Use of FFT and MDCT in MP3 Audio Compression" (PDF). University of Utah. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- Brandenburg, Karlheinz (1999). "MP3 and AAC Explained" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-13. Retrieved 2019-09-11.

- Motoyoshi, M. (2009). "Through-Silicon Via (TSV)". Proceedings of the IEEE. 97 (1): 43–48. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2008.2007462. ISSN 0018-9219. S2CID 29105721.

- "Tortoise of Transistors Wins the Race - CHM Revolution". Computer History Museum. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- "Transistors Keep Moore's Law Alive". EETimes. 12 December 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- Bazillion, Richard (2001). "Academic libraries in the digital revolution" (PDF). Educause Quarterly. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Lauer, Claire (2009). "Contending with Terms: "Multimodal" and "Multimedia" in the Academic and Public Spheres" (PDF). Computers and Composition. 26 (4): 225–239. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.457.673. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2009.09.001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-27.

- Ito, Mizuko; et al. (November 2008). "Living and learning with the new media: summary of findings from the digital youth project" (PDF). Retrieved 29 March 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Digital literacy definition". ALA Connect. 14 September 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- "What is digital literacy?". Cornell University Digital Literacy Resource. Cornell University. Archived from the original on 26 June 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- "History of Mobile Phones (1973 To 2008): The Cellphone Game-Changers!". Know Your Mobile. 2020-04-15. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- "Smartphone users by country 2019". Statista. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- "Current Trends And Future Prospects Of The Mobile App Market". Smashing Magazine. 2017-02-20. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- "Number of smartphone users worldwide 2014-2020 | Statista". Statista. Retrieved 2017-05-12.

- "Tablet Users to Surpass 1 Billion Worldwide in 2015 - eMarketer". www.emarketer.com. Retrieved 2017-05-12.

- "Apple announces 1 million apps in the App Store, more than 1 billion songs played on iTunes radio". The Verge. 2013-10-22. Retrieved 2017-05-12.

- Ingraham, Nathan (2013-10-22). "Apple announces 1 million apps in the App Store, more than 1 billion songs played on iTunes radio". The Verge. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- Cusumano, Catherine (18 March 2013). "Changeover in film technology spells end for age of analog". Brown Daily Herald. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Carter, Beth (26 April 2012). "Side by side takes digital vs. analog debate to the movies". Wired. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- McCracken, Erin (5 May 2013). "Last reel: Movie industry's switch to digital hits theaters -- especially small ones -- in the wallet". York Daily Record. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Thompson, Derek (2016-11-03). "The Print Apocalypse of American Newspapers". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- "Time Inc. spinoff reflects a troubled magazine business". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- Kirchhoff, Suzanne M. (9 September 2010). "The U.S. newspaper industry in transition" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Zara, Christopher (2 October 2012). "Job growth in digital journalism is bigger than anyone knows". International Business Times. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- "Publishing in the digital era" (PDF). Bain & Company. 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Toppo, Greg (31 January 2012). "Obama wants schools to speed digital transition". USA Today. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- "Trends and Facts on Newspapers | State of the News Media". Pew Research Center's Journalism Project. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- "Circulation, revenue fall for US newspapers overall despite gains for some". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- Horrigan, John (May 2007). "A Typology of Information and Communication Technology Users". Pew Internet and American Life Study. Archived from the original on 2014-01-12. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

- Pavlik, John; McIntosh, Shawn (2014). Converging Media (Fourth ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 237–239. ISBN 978-0-19-934230-3.

- Cohen, Cathy J.; Joseph Kahne (2012). "Participatory politics: new media and youth political action" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2014. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kelley, Peter (13 June 2013). "Philip Howard's new book explores digital media role in Arab Spring". University of Washington. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Rininsland, Andrew (16 April 2012). "Internet censorship listed: how does each country compare?". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- "Tablet Users to Surpass 1 Billion Worldwide in 2015 - eMarketer". www.emarketer.com. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- Crawford, Susan P. (3 December 2011). "Internet access and the new digital divide". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- "61% of young adults in U.S. watch mainly streaming TV". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- Roku. "Roku". Roku. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- "The Explosive Growth of Online Video, in 5 Charts". Contently. 2015-07-06. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- "Netflix: the rise of a new online streaming platform universe – Digital Innovation and Transformation". digital.hbs.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- "TV Shows That Found New Homes After Cancellation (Photos)". TheWrap. 2019-07-01. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- Ann Marie Sullivan, Cultural Heritage & New Media: A Future for the Past, 15 J. MARSHALL REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 604 (2016) https://repository.jmls.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1392&context=ripl

- "Copyright: an overview". Jisc Digital Media. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Barnett, Emma (18 May 2011). "Outdated copyright laws hinder growth says Government". The Telegraph. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Brunet, Maël (March 2014). "Outdated copyright laws must adapt to the new digital age". Policy Review. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Kloc, Joe (12 November 2013). "Outdated copyright law makes memes illegal in Australia". Daily Dot. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Alexander, Julia (2019-04-05). "The golden age of YouTube is over". The Verge. Retrieved 2020-04-27.

- Trotter, Andrew (17 October 2008). "The open-content movement". Digital Directions. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Santos Silva, Dora (June 14–15, 2012). "The Future of Digital Magazine Publishing" (PDF). In Baptista, A.A.; et al. (eds.). Social Shaping of Digital Publishing: Exploring the Interplay Between Culture and Technology. ELPUB - 16th International Conference on Electronic Publishing. Guimarães, Portugal. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- Jones, Ryan. "Are Digital Magazines Dead". WWW.wired.com. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- Pavlik, John; Mclntosh, Shawn (2014). Converging Media (fourth ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-19-934230-3.

Further reading

- Ramón Reichert, Annika Richterich, Pablo Abend, Mathias Fuchs, Karin Wenz (eds.), Digital Culture & Society.