Hyperodapedon

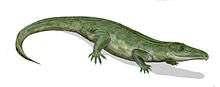

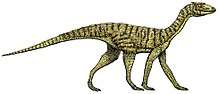

Hyperodapedon is a genus of rhynchosaurs (beaked, archosaur-like reptiles) from the Late Triassic period (Carnian stage). Fossils of the genus have been found in Africa, Asia, Europe and North and South America. Its first discovery and naming was found by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1859. Hyperodapedon was a herbivore that used its beaked premaxilla and hindlimbs to dig for plants in dry land.

| Hyperodapedon | |

|---|---|

| Hyperodapedon (formerly Scaphonyx) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Rhynchosauria |

| Family: | †Rhynchosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Hyperodapedontinae |

| Genus: | †Hyperodapedon Huxley 1859 |

| Type species | |

| †Hyperodapedon gordoni Huxley 1859 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Genus-level:

Species-level:

| |

Description

Hyperodapedon was a heavily built, stocky, animal around 1.3 metres (4.3 ft) in length. Apart from its beak, it had several rows of heavy teeth on each side of the upper jaw, and a single row on each side of the lower jaw, creating a powerful chopping action when it ate. It is believed to have been herbivorous, feeding mainly on seed ferns, and died out when these plants became extinct at the end of the Triassic.[1] The diagnosis of Hyperodapedon relies on many features of the cranial and postcranial traits which include a longer than wide basipterygoid process, a crest-shaped maxillary cross section next to the main longitudinal groove, deep excavated neural arches on the mid dorsal vertebrae, a long scapular blade, a pronounced deltopectoral crest, and a proximal humeral end which is broader at the distal end. The maxillary tooth plates are easily seen in Hyperodapedon and there are seven cranial, six postcranial, and three dentition synapomorphy traits.[2]

Hyperodapedon had jaws that allowed them to have a precision-shear bite to break down the tough plants that they ate. The beak-like premaxilla and hind limbs were used for digging up food. Teeth along the maxilla and dentary had open roots which could not be replaced like other reptiles. The forelimbs, on the other hand, were used for movement due to the rotation of; the humerus, however, the femur was not able to rotate. Another unique feature of Hyperodapedon was the large eyes with sclerotic plates, which allowed for good sense of vision. They had large nasal capsules to sense smell. Since Hyperodapedon lacked a tympanum, it was believed that they could sense sound by the skin near the quadrate.[3] Hyperodapedons also appeared to have transverse rows of cone-shaped teeth along the lateral area of the maxilla.[4]

Hyperodapedon's closest relative is Rhynchosaurus, and they both share a synapomorphy that the dentary is half the length of the lower jaw.[5] Hyperodapedon had a longitudinal stapedial canal on the posterior side of the spatulate paroccipital process which the lagenar crest extended laterally to limit the posterior end.[6] Above the ventral margin of the orbit was the upper temporal bar which faced dorsally.[2] A non-directional exploitation of morphospace from smaller ancestors with a smaller size restriction is responsible for a large body size in Hyperodapedon.[2] Hyperodapedon have a single row of teeth in mandible bites between their two rows of teeth fixed to a plate which is formed by a union of the maxilla with the palatine.[6] Other key traits are the two maxillary grooves and a single dentary blade, along with missing the infraorbital foramen. The supraoccipital and opisthotics are fused together.[7] Hyperodapedon had a pair of ridges which are absent on the pterygoid, they are missing the palatal dentition, and the prefrontal is concave deeply on the dorsal side.[8]

Discovery

The first discovery was from Thomas Henry Huxley in 1859, who named Hyperodapedon gordoni in honor of Rev. Dr. Gordon's contributions in Elgin County.[9]

T.H. Huxley found many series of subcylindical palatal teeth which was the main trait of Hyperodapedon. Huxley was able to distinguish Hyperodapedon from Rhynchosaurus articeps by the maxillary tooth rows. Later on, Lydekker realized that Hyperodapedon have more than two rows of teeth in both the maxilla and palatine.[3]

The type species of Scaphonyx (meaning canoe claw), Scaphonyx fischeri that was once thought to be a dinosaur, is now known to be based on dubious material and therefore should be a nomen dubium. The name Paradapedon was elected for the Indian species H. huxleyi (Lydekker, 1881). Benton, 1983, concluded that this rhynchosaur should be considered a species of Hyperodapedon.[9]

Hyperodapedon is known from several species and has been found in many areas of the world, due to the continents being joined together in the supercontinent Pangaea during the Triassic. Fossils from the various species have been identified from Argentina, Brazil, India, Scotland, Tanzania, Zimbabwe and possibly from Canada, and Wyoming (United States).[10]

Classification

Langer et al. (2000) defined Hyperodapedon as a stem-based taxon that includes all rhynchosaurs closer to Hyperodapedon gordoni than to "Scaphonyx" sulcognathus (now Teyumbaita).[7] The cladogram below follows their phylogenetic analysis of Mukherjee & Ray (2014).[2]

| Hyperodapedontinae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Valid species that were first assigned to Scaphonyx.

A quantitative phylogenetic analysis found a paraphyletic genus Rhynchosaurus, with Rhynchosaurus brodiei more closely related to hyperodapedontines than to Rhynchosaurus articeps. Hyperodapedon is the most commonly found tetrapod along the oldest dinosaur lineage which results in a broad biostratigraphic correlation.[8] Rhynchosaurs are archosauromorph diapsids which is believed to Trilophosaurus, and sister group to Prolacetiformes and Archosauria. A cladistic analysis of Rhynchosauria reveals that Hyperodapedontinae is a major subgroup of the late Triassic. Stenaulorychus and Rhynchosaurus are close outgroups to Hyperdapedontinae during the middle Triassic. They share the synapomorphy of the dentary is well over half the length of the lower jaw. Rhynchosaurs were basal archosauromorphs that were herbivorous on dry land in Triassic Pangea. Some rare forms are Mesosuchus and Howesia. Hyperodapedon and Scaphonyx are included in the subfamily of Hyperodapedontinae.[3][11] Hyperodapedontinae consist of Hyperodapedon huxleyi and Scaphonyx sulcognathus.[11]

Palaeoecology

Hyperodapedon are commonly found in aeolian sand in Elgin, India, Brazil, and Argentina.[3] They are a widely distributed tetrapod during the Upper Triassic and are present in locations where phytosaurs are absent.[4] Hyperodapedon localities are found in the Popo Agie Formation in Wyoming and the Wolfville Formation in Nova Scotia that date to the Otischalkian. They are also found in Scotland in the Lossiemouth Sandstone dating to the Adamanian, Maleri Formation in India, Pebbly Arkose Formation in Zimbabwe, Isalo II Beds in Madagascar, Ischigualasto Formation in Argentina, and Santa Maria Formation in Brazil that vary between Otischalkian and Adamanian.[10] Similarly, Rhynchosaurus is found in fluvial-intertidal deposits with desiccation along with aeolian deposits with common flash floods.[12]

Distribution

Fossils of Hyperodapedon have been found in:[13]

- Ischigualasto Formation, Argentina

- Caturrita and Santa Maria Formations, Brazil

- Wolfville Formation, Nova Scotia, Canada

- Lower Maleri and Tiki Formations, India

- Ruvuma, Tanzania

- Lossiemouth Sandstone, Scotland

- Popo Agie Formation, Wyoming, United States

- Pebbly Arkose Formation, Zimbabwe

References

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-84028-152-1.

- Mukherjee, D., Ray, S. (2014), A new Hyperodapedon (Archosauromorpha, Rhynchosauria) from the Upper Triassic of India: implications for rhynchosaur phylogeny. Palaeontology. doi: 10.1111/pala.12113

- Benton, M. (1983). The Triassic reptile Hyperodapedon from Elgin: Functional morphology and relationships. Royal Society.

- Huxley, T. (1887). Further Observations upon Hyperodapedon gordoni. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, 43, 675-694.

- Benton, M. J. (1990). The Species of Rhynchosaurus, A Rhynchosaur (Reptilia, Diapsida) from the Middle Triassic of England. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 328(1247), 213-306. doi:10.1098/rstb.1990.0114

- Langer, M. C., & Schultz, C. L. (2003). A New Species Of The Late Triassic Rhynchosaur Hyperodapedon From The Santa Maria Formation Of South Brazil. Wiley Online Library, 43(4).

- Max C. Langer and Cesar L. Schultz (2000). "A new species of the Late Triassic rhynchosaur Hyperodapedon from the Santa Maria Formation of south Brazil". Palaeontology. 43 (6): 633–652. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00143.

- Ezcurra, M. D., Montefeltro, F., & Butler, R. J. (2016). The Early Evolution of Rhynchosaurs. Front. Ecol

- Burckhardt, R. (1900). I.—On Hyperodapedon gordoni. Geological Magazine,7(12), 529. doi:10.1017/s0016756800183529

- Lucas, S. G. (2002). The Hyperodapedon Biochron, Late Triassic of Pangea. Albertiana.

- Huxley, T. (1869). On Hyperodapedon. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, 25, 138-152.

- Benton, M. J. (1990). The Species of Rhynchosaurus, A Rhynchosaur (Reptilia, Diapsida) from the Middle Triassic of England. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 328(1247), 213-306. doi:10.1098/rstb.1990.0114

- Hyperodapedon at Fossilworks.org

External links