Doswellia

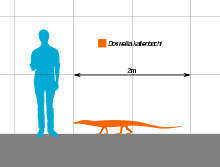

Doswellia is an extinct genus of archosauriform from the Late Triassic of North America. It is the most notable member of the family Doswelliidae, related to the proterochampsids. Doswellia was a low and heavily built carnivore which lived during the Carnian stage of the Late Triassic.[1] It possesses many unusual features including a wide, flattened head with narrow jaws and a box-like rib cage surrounded by many rows of bony plates. The type species Doswellia kaltenbachi was named in 1980 from fossils found within the Vinita member of the Doswell Formation (formerly known as the Falling Creek Formation) in Virginia. The formation, which is found in the Taylorsville Basin, is part of the larger Newark Supergroup. Doswellia is named after Doswell, the town from which much of the taxon's remains have been found. A second species called D. sixmilensis was described in 2012 from the Bluewater Creek Formation of the Chinle Group in New Mexico;[1] however, this species was subsequently transferred to the separate doswelliid genus Rugarhynchos.[2]

| Doswellia | |

|---|---|

| |

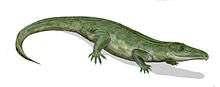

| Life restoration of Doswellia kaltenbachi in mid-stride | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | †Proterochampsia |

| Family: | †Doswelliidae |

| Genus: | †Doswellia |

| Type species | |

| Doswellia kaltenbachi Weems, 1980 | |

| Species | |

| |

Discovery

The most complete specimens of Doswellia were discovered in 1974 during the construction of a sewage treatment plant in Doswell, Virginia. A party led by James Kaltenbach (the namesake of Doswellia kaltenbachi) unearthed a large block containing a partial skeleton, including numerous vertebrae, ribs, osteoderms (bony plates), and other bones. This block, USNM 244214, has been designated the holotype of D. kaltenbachi. Two additional slabs were later unearthed at the same site and almost certainly pertained to the same individual. One of these slabs contained additional vertebrae and ribs while the other contained a partial skull and mandible. These additional slabs were collectively termed the paratype, USNM 214823. An isolated right jugal found at the site (USNM 437574) was also referred to the species.[3]

In the 1950s and 1960s, several additional bones (including vertebrae, osteoderms, a dentary, and a femur) were unearthed near Ashland, a little south of Doswell. These specimens were initially believed to have belonged to phytosaurs, but were recognized as pertaining to Doswellia after the Doswell specimens were found. The Ashland specimens are cataloged as USNM 186989 and USNM 244215.[4]

In 2012, a second species, Doswellia sixmilensis, was described. This species hailed from Sixmile canyon in McKinley County, New Mexico. The holotype of this species is NMMNH P-61909, an incomplete skeleton including skull fragments, osteoderms, vertebrae, and possible limb fragments.[1] Doswellia sixmilensis was later given its own genus, Rugarhynchos, in 2020.[2]

Assorted osteoderms and vertebrae from the Otis Chalk and Colorado City Formation in Texas, as well as the Monitor Butte Formation in Utah have also been assigned to Doswellia.[5][1]

Description

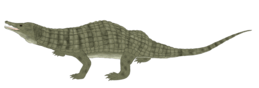

Doswellia possesses many highly derived features in its skeleton. The skull is low and elongated with a narrow snout and wide temporal region behind the eye sockets. The temporal region is unusual in that it is euryapsid, which means that the lower of the two temporal holes on either side of the skull has closed. The jugal bone has expanded into the region the lower temporal opening would normally occupy. Paired squamosal bones extend beyond the skull's back margin to form small horn-like projections. The skull of Doswellia lacks several bones found in other archosauriforms, including the postfrontals, tabulars, and postparietals.[3]

The body of Doswellia is also distinctive. The neck is elongated and partially covered by a fused collection of bony scutes called a nuchal plate. The ribs in the front part of the torso project horizontally from the spine and then bend at nearly 90-degree angles to give the body of Doswellia a box-like shape. The blade-like ilium bone of the hip also projects horizontally. Rows of osteoderms stretched from the nuchal plate to the tail. At least ten rows covered the widest part of Doswellia's back.[3]

Paleobiology

Jaw functionality

The quadratojugal and surangular bones (on the cranium and lower jaw, respectively) were both incorporated into the jaw joint, reinforcing the joint and preventing side-to-side or front-to back movement. As a result, the jaws of Doswellia would have been incapable of any notable form of movement other than vertical scissor-like snapping. In addition, the expanded back of the skull and very deep rear part of the lower jaw likely housed muscles that could let the jaw both open and close with a high amount of force. This contrasts with modern crocodilians, which have a powerful bite but a much weaker ability to open their jaws. Nevertheless, the high amount of sculpturing in the skull of Doswellia is similar to the skulls of modern crocodilians. It is likely an adaptation to minimize stresses in the skull during a powerful bite.[4]

Diet and life habits

The pointed teeth, long snout, and upward-pointing eyes of Doswellia are support for the idea that it was an aquatic carnivore. In addition, its relatively compact osteoderms are also evidence for an aquatic lifestyle.[6] However, it may not necessarily have been strictly aquatic, as these features are also found in animals such as Parasuchus, a phytosaur which is known to have preyed on terrestrial reptiles such as Malerisaurus. Other possible food sources include crustaceans, bivalves, and (most speculatively) large flying or hopping insects. It is also conceivable that it was capable of limited burrowing either for shelter (as in alligators) or defense, partially burying itself to keep its armor exposed yet protect its soft underside. This technique is used by modern armadillos, echidnas and Cordylus lizards. The front limbs are unknown in Doswellia, so there is no direct evidence for burrowing adaptations.[4]

Movement

The neck of Doswellia was long and flexible, although also heavily armored, so it was likely incapable of bending above the horizontal, instead probably being used more for downwards and lateral (side-to-side) movement. The body was also probably incapable of moving up and down to much of an extent due to the extensive and overlapping armor plating which characterizes the genus. The chest would have been much more likely to have flexed laterally (like most living reptiles and amphibians) while the animal was walking. The first few tail vertebrae were similar to the body vertebrae, so the front of the tail would probably have been held level with the body. The rest of the tail would have been more capable of bending downward, but lacked many adaptations for lateral movement. This means that, if Doswellia was an aquatic predator, it probably would not have used its tail for swimming as in modern crocodilians. Although limb material is not well known in Doswellia, material that is preserved suggests that both the front and rear legs were strongly built. Although the bizarre downward pointing hip could have given Doswellia an upright posture as in dinosaurs (including the armored ankylosaurs), various other primitive features suggest that it was more likely to have been sprawling or semi-sprawling most of the time.[4]

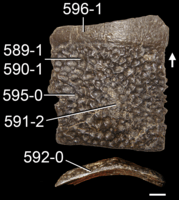

Histology and osteoderm development

In 2017, an osteoderm from the Doswellia holotype was given a histological analysis to study growth patterns. The analysis concluded that the osteoderm formed by "intramembraneous ossification" due to the lack of structural fibers within it. This means that the bone of the osteoderm formed from a soft layer of periosteal tissue, rather than fibrous tendons or cartilage. Growth marks within the bone indicate that the holotype specimen of Doswellia died at 13 years of age. Perhaps the most unique aspect of Doswellia's osteoderm development lies in the fact that the ridges formed from the bone instead of the pits. In most prehistoric armored animals with pitted ostoderms, the pitting pattern formed due to specific spots of the bone being reabsorbed, creating pits. This even holds true to other doswelliids such as Jaxtasuchus. However, the studied osteoderm of Doswellia shows no evidence for reabsorption of specific areas, instead showing increased amounts of bone growth in the web of ridges which surround the pits. Although certain "rauisuchians" (non-crocodylomorph paracrocodylomorph archosaurs) also have osteoderms which form from bone growth in specific areas, their osteoderms are relatively smooth rather than pitted. Vancleavea, a supposed relative of Doswellia which also had its osteoderms analyzed, differed from the genus in multiple ways.[6]

Classification

The type species, Doswellia kaltenbachi, was described by Weems in 1980.[4] Weems placed Doswellia within Thecodontia, a group of archosaurs that traditionally included many Triassic archosaurs. He placed the genus within its own family, Doswelliidae, and suborder, Dosweliina. Parrish (1993) placed Doswellia among the most primitive of the crurotarsans, a group that includes crocodilians and their extinct relatives. More recently, Dilkes and Sues (2009) proposed a close relationship between Doswellia and the early archosauriform family Proterochampsidae. Desojo et al. (2011) added the South American archosauriforms Tarjadia and Archeopelta to Doswelliidae, and found support for Dilkes and Sues' classification in their own phylogenetic analysis.[7] Although Tarjadia and Archeopelta are now considered to be erpetosuchids only distantly related to Doswellia, the family Doswelliidae is still considered valid due to other taxa (such as Jaxtasuchus from Germany and Ankylosuchus from Texas) being considered close relatives of Doswellia.

References

- Heckert, Andrew B.; Lucas, Spencer G.; Spielmann, Justin A. (2012). "A new species of the enigmatic archosauromorph Doswellia from the Upper Triassic Bluewater Creek Formation, New Mexico, USA". Palaeontology. 55 (6): 1333–1348. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2012.01200.x.

- Brenen M. Wynd; Sterling J. Nesbitt; Michelle R. Stocker; Andrew B. Heckert (2020). "A detailed description of Rugarhynchos sixmilensis, gen. et comb. nov. (Archosauriformes, Proterochampsia), and cranial convergence in snout elongation across stem and crown archosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. in press: e1748042. doi:10.1080/02724634.2019.1748042.

- Dilkes, D.; Sues, H. D. (2009). "Redescription and phylogenetic relationships of Doswellia kaltenbachi (Diapsida: Archosauriformes) from the Upper Triassic of Virginia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29: 58. doi:10.1080/02724634.2009.10010362.

- R. E. Weems (1980). "An unusual newly discovered archosaur from the Upper Triassic of Virginia, U.S.A." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. New Series. 70 (7): 1–53. doi:10.2307/1006472.

- Long, Robert A.; Murry, Phillip A. (1995). "Late Triassic (Carnian and Norian) Tetrapods from the Southwestern United States". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 4: 1–238.

- Ponce, Dennis A.; Cerda, Ignacio A.; Desojo, Julia B.; Nesbitt, Sterling J. (2017). "The osteoderm microstructure in doswelliids and proterochampsids and its implications for palaeobiology of stem archosaurs" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 62 (4): 819–831. doi:10.4202/app.00381.2017.

- Julia B. Desojo, Martin D. Ezcurra and Cesar L. Schultz (2011). "An unusual new archosauriform from the Middle–Late Triassic of southern Brazil and the monophyly of Doswelliidae". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 161 (4): 839–871. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00655.x.