Shringasaurus

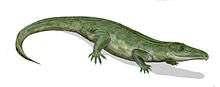

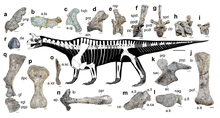

Shringasaurus (meaning "horned lizard", from Sanskrit शृङ्ग (śṛṅga), "horn", and Ancient Greek σαῦρος (sauros), "lizard") is an extinct genus of archosauromorph reptile from the Middle Triassic (Anisian) of India. It is known from the type and only known species, S. indicus. Shringasaurus is known from the Denwa Formation in the state of Madhya Pradesh. Shringasaurus was an allokotosaur, a group of unusual herbivorous reptiles from the Triassic, and is most closely related to the smaller and better known Azendohsaurus in the family Azendohsauridae. Like some ceratopsid dinosaurs, Shringasaurus had two large horns over its eyes that faced up and forwards from its skull. These horns were likely used for display, and possibly during fights with other Shringasaurus, much like what has been suggested for the horns of ceratopsids like Triceratops. Shringsaurus also bears similarities to sauropodomorph dinosaurs, such as its long neck and teeth, and likely occupied a similar ecological niche as a large browsing herbivore before they had evolved.

| Shringasaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

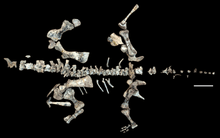

| Composite skeleton from the fossils of multiple individuals | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauromorpha |

| Clade: | Crocopoda |

| Clade: | †Allokotosauria |

| Family: | †Azendohsauridae |

| Genus: | †Shringasaurus Sengupta et al., 2017 |

| Species: | †S. indicus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Shringasaurus indicus Sengupta et al., 2017 | |

Description

Shringasaurus was a large-bodied quadruped, with an estimated body length of 3–4 metres (9.8–13.1 ft) long. Its closely resembles the related Azendohsaurus, with a small, boxy head on a long neck and a large, barrel-shaped body with deep shoulders and ribs, sprawled to semi-sprawled limbs and a short tail. Aside from being notably larger than Azendohsaurus, Shringasaurus is most recognisable for its long curving brow horns, as well as having a proportionately shorter and thicker neck than other azendohsaurids with much taller neural spines in the neck and over the shoulders.[1][2]

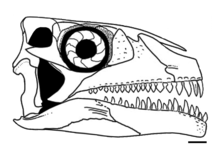

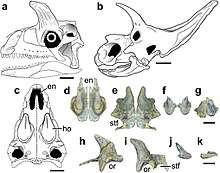

Skull

The skull of Shringasaurus is not completely known, but what's preserved indicates that the skull was small and boxy, with a short, deep snout with rounded jaw tips and bony nostrils fused into a single, confluent opening at the front of the snout. This is broadly similar to the completely known skull of Azendohsaurus, however the lower jaw of Shringasaurus has a more conspicuous taper towards the tip compared to the deep, down-turned dentary of Azendohsaurus.[1][3]

The horns of Shringasaurus closely resemble those seen in ceratopsid dinosaurs, despite being totally unrelated to each other. The horns are attached to the frontal bones on the roof of the skull over the eyes, and sit across almost the entire breadth of the skull. These horns are pointed up and curve forwards from the skull, with slight variation in size and orientation between large individuals. Smaller and younger individuals had smaller, more gracile horns, indicating that the horns did not fully develop until the animals were mature. Intriguingly, at least one small specimen lacks horns entirely, whereas another similarly small specimen has small but well developed horns. It is suggested then that Shringasaurus was sexually dimorphic, and that possibly the females lacked horns.[1]

The horns themselves have a rough, grooved texture that implies they were covered with a keratinous sheath of horn in life, also like ceratopsid horns, and so would have likely been longer than the bony cores indicate.[4][5] The bones of the skull beneath the horns are unusually thick, and in the larger individuals the bones of roof of the skull (the nasal, prefrontal, frontal and postfrontal) are fused together on each side.[1]

The teeth of Shringasaurus are low and leaf-shaped (lanceolate) with large denticles on either side, similar in shape to those of Azendohsaurus but lacking the prominent expansion above the root, like the teeth of Pamelaria. Because the skull and jaws are incompletely known, the total tooth count of Shringasaurus is unknown, but like Azendohsaurus it had four teeth in each premaxilla. Shringasaurus also had numerous palatal teeth (though known only from the vomer thus far), and like Azendohsaurus they are uniquely as well developed as the marginal teeth along the edge of the jaw. Like them, they were leaf-shaped and serrated, but in Shringasaurus the palatal teeth are even more lanceolate than the marginal rows.[1] Such palatal teeth are unusual, as most other herbivorous reptiles with them have much simpler, domed palatal teeth, and palatal teeth identical to those of the jaw margins are otherwise only found in the related allokotosaurs Azendohsaurus and Teraterpeton.[3][6]

Skeleton

The vertebral column is well known in Shringasaurus, including the whole cervical series, various dorsal vertebrae, both sacral vertebrae and some caudal vertebrae. Like other azendohsaurids, the first-through-middle cervical vertebrae are characteristically elongated, giving Shringasaurus a long, raised neck, although it is proportionately shorter than in Azendohsaurus and Pamelaria. The neck is also much taller than in other azendohsaurids, with tall, prominent neural spines. This trend continues into the dorsals of the back, which although are not as long as the cervicals have neural spines twice the height of their centra. The 2nd–5th cervicals of Shringasaurus sport prominent epipophyses, structures for supporting neck musculature, suggesting Shringasaurus had strong neck muscles.[7] The first twelve dorsals are also marked by various well-defined laminae that bound deep fossae (depressions in the bone), similar to those found on the vertebrae of sauropods. Like Azendohsaurus, Shringasaurus has two sacral vertebrae with well-developed ribs that articulate with the ilia.[1]

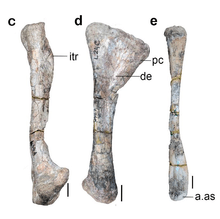

The shoulder and forelimb are broadly similar to those of Azendohsaurus, with a tall scapula that is concave along the front with an expanded tip, and an interclavicle with a long paddle-like process on the back and a short forward-pointing process (an unusual feature for archosauromorphs but also found in Azendohsaurus). The coracoid articulates with the scapula to form a glenoid (shoulder socket) that faces out to the sides and back, a feature in Azendohsaurus suggested to indicate the forelimb was held more upright than a full sprawl.[2] The humerus is likewise similar, with broad ends and a narrow midshaft, and a very well-developed deltopectoral crest half as long as the whole bone, indicating powerful forelimbs. The ulna, however, can be distinguished by a lower olecranon process below the elbow than in Azendohsaurus.[1]

The hips and hind limbs are very similar to those of Azendohsaurus. The ilium has a prominent, semi-circular process at the front while the rear process is longer and thinner, and the acetabulum (hip socket) is also solid, unlike the perforated hip socket of dinosaurs. The femur is robust and slightly s-shaped, held out to the sides in a sprawl, with a robust tibia and a fibula only half as wide in the lower leg. The foot is typical for early archosauromorphs, including Azendohsaurus.[1][2]

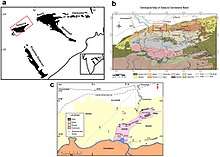

Discovery and naming

Shringasaurus is known from a single bone bed of fossils in the upper Denwa Formation, India. The formation is part of the Satpura Gondwana Basin, located in the Hoshangabad district in the state of Madhya Pradesh. The precise age of the Denwa Formation is not known, but vertebrate biostratigraphy has been used to narrow it down to a range in the early Middle Triassic with conflicting opinions on an early or late Anisian age.[8][9] The upper Denwa Formation is characteristically dominated by red mudstones with ribbon-shaped sandstone sheets encased within them.[1]

The Shringasaurus bone bed consists of mostly disarticulated bones scattered in a 25 square metres (270 sq ft) area of red mudstone, although one skeleton was found partially articulated, and only contains fossils of Shringasaurus. At least seven to eight individuals were recovered from the bone bed, based on the number of different left humeri, skull roofs and horns discovered, and they are all from varying ontogenetic stages of growth with a wide range of body sizes. Of these individuals, only one or two lacked horns, and it's suggested that the bone bed was taphonomically biased towards the heavier, solidly built skulls of horned individuals while being transported and preserved.[1][10]

The fossils were excavated and prepared by Professor Saswati Bandyopadhyay, Dhurjati Sengupta and Shiladri Das of the Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, where the fossils are also stored. It was then described and named in August 2017 by Sarandee Sengupta and Bandyopadhyay, as well as by Martín D. Ezcurra of the Bernardino Rivadavia Natural Sciences Argentine Museum in Argentina. The holotype specimen, ISIR 780, consists of a partial skull roof including the prefrontal, frontal, postfrontal and parietal bones, along with a pair of large supra-orbital horns. The various other specimens from the bone bed have been designated as paratypes and consist of multiple cranial and postcranial bones from much of the skeleton. The genus was named using the ancient Sanskrit word for "horn", 'Śṛṅga' (शृङ्ग), for the unique horns on its skull, combined with the Ancient Greek σαῦρος (sauros) for "lizard". The species name indicus is Latin for "Indian", to refer to its country of discovery.[1]

Classification

Shringasaurus is recognised as a member of the family Azendohsauridae, and as the closest relative of Azendohsaurus itself. The family is typically grouped within the recently recognised clade Allokotosauria, along with the trilophosaurids, as was recovered by Sengupta and colleagues when they described Shringasaurus and analysed its phylogenetic relationships in 2017.[1] Another analysis of archosauromorph relationships in 2019 that used a different dataset from Sengupta et al. (2017)—that of Pritchard et al. (2018)[11]—was updated to include Shringasaurus, and similarly recovered it and Azendohsaurus as each other's closest relatives within Allokotosauria, further supporting an azendohsaurid affinity for Shringasaurus.[12]

The results found by Sengupta and colleagues in 2017 is shown below as an excerpt of the full cladogram, simplified and focused on the relationships of Shringasaurus to other allokotosaurs:[1]

| Crocopoda |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Shringasaurus and other azendohsaurids share several features, including confluent nares, leaf-shaped teeth and a long neck, as well as a few other minor details of the skeleton. It is particularly similar to Azendohsaurus in features of the pareitals, the lower jaw, shoulder, hip, femur and vertebrae, but can be distinguished by teeth that are not expanded above the roots, the lack of a groove on the inside surface of the maxilla, tall neural spines, and of course the horns.[1]

Palaeobiology

Function of the horns

The horns of Shringasaurus are its most prominent feature, and so some focus was placed on their role and function in its initial description. Its describers considered its horns to be likely products of sexual selection, not primarily for defence or species recognition (as has been proposed for the head ornaments of dinosaurs).[13] The horns grow notably larger and more robust in large adults, while smaller individuals have shorter and more graceful horns. The possibility that Shringasaurus was sexually dimorphic, with probable females lacking horns, further supports this interpretation. This would be similar to modern horned bovids, but unlike ceratopsid dinosaurs, and indeed other archosauromoromorphs, which do not appear to have been dimorphic.[1]

Furthermore, the size and shape of the horns has been compared to those of other horned animals, and the relatively short, curved horns were most similar to those of animals that wrestle with their horns, as opposed to ramming, stabbing and fencing. Male Shringasaurus then may have competed for mates by locking their horns together, remarkably similar to what is inferred for the horned ceratopsid dinosaurs (particularly Triceratops)[14] and the modern reedbuck antelope.[1][15]

Palaeopathology

One specimen of Shringasaurus is known to have had a pair of malformed vertebrae in its neck. The two cervicals are partially fused together, interpreted as either the result of a birth defect, spondyloarthropathy (a type of arthritis), or possibly a bacterial or fungal disc infection. The vertebrae belonged to a large adult animal, so it is unlikely that the quality of life for the individual was severely affected by the disorder, and it was probably not fatal to the animal. One of the vertebrae also preserves a healed fracture, although the cause for this injury is unknown.[10]

Palaeoecology

In the upper Denwa Formation, Shringasaurus coexisted with the lungfish Ceratodus sp. and a variety of temnospondyl amphibians, including the capitosaurid Paracyclotosaurus crookshanki, the mastodonsaurid Cherninia denwai, a lonchorhynchine trematosaurid, and a brachyopid. Other terrestrial vertebrates include a large undescribed rhynchosaur and two species of dicynodonts, a mid-sized species similar to Kannemeyeria and a larger species interpreted as similar to Stahleckeria.[1][8][16] The environment is interpreted as representing a dry, semi-arid floodplain with slow moving, anabranching rivers that periodically burst their banks. Rainfall was seasonal, and the environment experienced droughts that dried up ephemeral rivers and ponds.[1][16][17] The large body size of Shringasaurus and its similarity to sauropodomorphs—including its jaws and teeth as well as a superficially similar body shape—suggests that it occupied the role of a large, relatively high-browsing herbivore in its environment, similar to what is suggested for Azendohsaurus.[1][2]

References

- Sengupta, S.; Ezcurra, M.D.; Bandyopadhyay, S. (2017). "A new horned and long-necked herbivorous stem-archosaur from the Middle Triassic of India". Scientific Reports. 7: 8366. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08658-8. PMC 5567049. PMID 28827583.

- Nesbitt, S.J.; Flynn, J.J.; Pritchard, A.C.; Parrish, M.J.; Ranivoharimanana, L.; Wyss, A.R. (2015). "Postcranial osteology of Azendohsaurus madagaskarensis (?Middle to Upper Triassic, Isalo Group, Madagascar) and its systematic position among stem archosaur reptiles". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History (398): 1–126. doi:10.5531/sd.sp.15. hdl:2246/6624. ISSN 0003-0090.

- Flynn, J.J.; Nesbitt, S.J.; Parrish, J.M.; Ranivoharimanana, L.; Wyss, A.R. (2010). "A new species of Azendohsaurus (Diapsida: Archosauromorpha) from the Triassic Isalo Group of southwestern Madagascar: cranium and mandible". Palaeontology. 53 (3): 669–688. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00954.x.

- Hieronymus, T. L.; Witmer, L. M.; Tanke, D. H.; Currie, P. J. (2009). "The facial integument of centrosaurine ceratopsids: morphological and histological correlates of novel skin structures". The Anatomical Record. 292 (9): 1370–1396. doi:10.1002/ar.20985. PMID 19711467.

- Brown, C.M. (2017). "An exceptionally preserved armored dinosaur reveals the morphology and allometry of osteoderms and their horny epidermal coverings". PeerJ. 5: e4066. doi:10.7717/peerj.4066. PMC 5712211. PMID 29201564.

- Sues, Hans-Dieter (2003). "An unusual new archosauromorph reptile from the Upper Triassic Wolfville Formation of Nova Scotia" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 40 (4): 635–649. doi:10.1139/e02-048. ISSN 0008-4077.

- Brusatte, Stephen L. (2012). Dinosaur Paleobiology (1. ed.). New York: Wiley, J. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-470-65658-7.

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Sengupta, D. P. (1999). "Middle Triassic vertebrates of India". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 29 (1): 233–241. doi:10.1016/S0899-5362(99)00093-7.

- Abdala, F.; Hancox, P. J.; Neveling, J. (2005). "Cynodonts from the uppermost Burgersdorp Formation, South Africa, and their bearing on the biostratigraphy and correlation of the Triassic Cynognathus Assemblage Zone". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (1): 192–199. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0192:CFTUBF]2.0.CO;2.

- Sengupta, S. (2018). "Fusion of cervical vertebrae from a basal archosauromorph from the Middle Triassic Denwa Formation, Satpura Gondwana Basin, India". International Journal of Paleopathology. 20: 80–84. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2017.10.010.

- Pritchard, Adam C.; Gauthier, Jacques A.; Hanson, Michael; Bever, Gabriel S.; Bhullar, Bhart-Anjan S. (2018-03-23). "A tiny Triassic saurian from Connecticut and the early evolution of the diapsid feeding apparatus". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 1213. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03508-1. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5865133. PMID 29572441.

- Pritchard, A.C.; Sues, H.D. (2019). "Postcranial remains of Teraterpeton hrynewichorum (Reptilia: Archosauromorpha) and the mosaic evolution of the saurian postcranial skeleton". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 17: 1–21. doi:10.1080/14772019.2018.1551249.

- Hone, D.W.E.; Naish, D. (2013). "The 'species recognition hypothesis' does not explain the presence and evolution of exaggerated structures in nonavialan dinosaurs". Journal of Zoology. 290 (3): 172–180. doi:10.1111/jzo.12035.

- Farlow, J.O.; Dodson, P. (1975). "The behavioral significance of frill and horn morphology in ceratopsian dinosaurs". Evolution. 29 (2): 353–361. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1975.tb00214.x. PMID 28555861.

- Lundrigan, B. (1996). "Morphology of horns and fighting behavior in the Family Bovidae". Journal of Mammalogy. 77 (2): 462–475. doi:10.2307/1382822.

- Mukherjee, D.; Sengupta, D.P.; Rakshit, N. (2019). "New biological insights into the Middle Triassic capitosaurs from India as deduced from limb bone anatomy and histology". Papers in Palaeontology (Online edition). doi:10.1002/spp2.1263.

- Ghosh, P.; Sarkar, S.; Maulik, P. (2006). "Sedimentology of a muddy alluvial deposit: Triassic Denwa Formation, India". Sedimentary Geology. 191 (1–2): 3–36. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2006.01.002.

External links

- Indian Statistical Institute's director's report, September 16th 2017 – A report by Prof. Sanghamitra Bandyopadhyay for the ISI that includes several photos of the Shringasaurus bone bed during its excavation.