Asilisaurus

Asilisaurus (/ɑːˌsiːliːˈsɔːrəs/ ah-SEE-lee-SOR-əs; from Swahili, asili ("ancestor" or "foundation"), and Greek, σαυρος (sauros, "lizard") is an extinct genus of silesaurid archosaur. The type species is Asilisaurus kongwe. Asilisaurus fossils were uncovered in the Manda Beds of Tanzania and date back to the Anisian stage of the Middle Triassic (~245 million years ago), making it one of the oldest known members of the Avemetatarsalia (animals on the dinosaur/pterosaur side of the archosaurian family tree). It was the first non-dinosaurian dinosauriform recovered from Africa.The discovery of Asilisaurus has provided evidence for a rapid diversification of avemetatarsalians during the Middle Triassic, with the diversification of archosaurs during this time previously only documented in pseudosuchians (crocodylian-line archosaurs).[1][2]

| Asilisaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeletal cast PR 3062 on display at the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, USA. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dracohors |

| Clade: | †Silesauridae |

| Genus: | †Asilisaurus Nesbitt et al., 2010 |

| Species: | †A. kongwe |

| Binomial name | |

| †Asilisaurus kongwe Nesbitt et al., 2010 | |

Asilisaurus is known from a relatively large amount of fossils compared to most non-dinosaur dinosauromorphs. This has allowed it to provide important information for the evolution of other silesaurids and the origin of dinosaurs. It had several unique features compared to its close relatives, such as a lack of teeth at the front of the premaxilla and a lower jaw which was not only toothless at the tip, but also downturned. These indicate that it probably had a small beak on the tip of the snout. It was fairly basal among silesaurids, and retained some dinosaur-like features absent in advanced silesaurids, such as a supratemporal fossa and a quadrate which overlaps the squamosal. On the other hand, it also retains primitive features contrasting with dinosaurs, including two hip vertebrae, a closed hip socket, a crurotarsal ankle, and a non-vestigial fifth toe of the foot.[1][2]

Discovery

Asilisaurus was described in 2010 by a team of researchers from the United States, Germany, and South Africa, in the journal Nature. The generic name is derived from asili, the Swahili word for "ancestor" or "foundation", as well as σαυρος (sauros), the Greek word for "lizard". This refers to its position as an early avemetatarsalian which helps provide details for the evolution of dinosaurs. The specific name kongwe is in line with this naming scheme, as it is the Swahili word for "ancient".[1] The first remains of Asilisaurus were found in 2007 at "locality Z34", a bonebed near the town of Litumba Ndyosi in Tanzania. This bonebed is part of the Lifua Member of the Manda Beds, which preserves a middle Triassic lake ecosystem. At least 14 individuals were present at the site, including NMT RB9, the holotype dentary. Fossils likely belonging to Asilisaurus are known from throughout the Manda Beds. Numerous fragments of small individuals have been found at another site, "locality Z90". NMT RB159, a well-preserved and articulated partial specimen, was found at "locality Z137" and described in 2019.[3][1][2]

Description

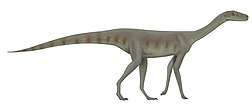

Asilisaurus was a lightly-built animal with a fairly long neck (by early archosaur standards), a short snout tipped with a beak, and slender limbs. It probably walked on all four legs based on the length of its limbs. Asilisaurus specimens have been estimated to measure from 1 to 3 metres (3 to 10 ft) long and 0.5 to 1 metre (2 to 3 ft) high at the hip, and may have weighed 10 to 30 kilograms (20 to 70 lb).[3] The ~3 meter upper length estimate is based on NHMUK R16303, an incomplete silesaurid femur found in the Manda Beds. This femur had an estimated length of 29.6-39.6 cm (11.7-15.6 in), more than twice the length of the next largest Asilisaurus femurs. The specimen belonged to one of the largest known pre-Norian avemetatarsalians, only exceeded by some Herrerasaurus specimens. Uncertainty over the stratigraphic position of the specimen and a lack of unambiguously Asilisaurus-like traits means that it is not certain that NHMUK R16303 belongs to Asilisaurus.[4]

Skull

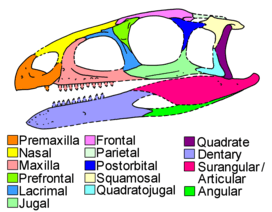

The overall skull was short, with a small nasal opening and a large and round orbit. The premaxilla is large and primarily toothless, with a sharp lower edge converging towards a pointed front tip. There is only a single tooth at the rear of the bone, near the contact with the maxilla. Other basal dinosauromorphs (even other silesaurids) had teeth along the entirety of the premaxilla. Other aspects, such as the shape of the posterodorsal process and the loose contact between adjacent premaxillae, are similar to other silesaurids. This is also the case with the palatal process of the maxilla, which has a flat surface separated from the rest of the bone via a ridge and pit. However, Asilisaurus's palatal process of the maxilla is much taller than other silesaurids. The antorbital fossa of the maxilla is shallow and poorly defined. There were at least 10 teeth in the maxilla, possibly up to 12 assuming that the rear part of the maxilla (which was not preserved) was similar to that of Silesaurus and Sacisaurus. Like other silesaurids, the teeth were ankylothecodont, set in sockets but also fused to the bone through small ridges. The teeth are conical, pointed, and slightly recurved. Some specimens' teeth have poorly developed serrations, while others are more prominent.[2]

The rest of the skull generally resembles Silesaurus and Lewisuchus, with some exceptions. The prefrontal is large and has a pronounced lateral "swelling" in front of the eye. The rear of the frontal has a pronounced supratemporal fossa like Teleocrater and dinosaurs, but unlike other silesaurids. Just lateral to the fossa, the frontal has a straight (rather than embayed) contact with either the postfrontal or postorbital. Neither preservation nor phylogenetic bracketing are stable enough to determine whether a postfrontal bone was present, or instead lost (which is the situation in dinosaurs). Also like dinosaurs, the quadrate partially overlaps part of the squamosal in lateral view. The front tip of the jugal is pointed, wedging between a wide lower banch of the lacrimal and a presumably sloping rear portion of the maxilla. The ectopterygoid has a curved jugal process and a deep ventral fossa, similar to Lewisuchus and theropod dinosaurs.[2]

Like the premaxilla, the front of the dentary is toothless and curves into a point. The tip bends down, in contrast to other silesaurids where it bends up. In addition, advanced silesaurids have a longitudinal groove at the lower edge of the inner portion of the dentary, while that of Asilisaurus is positioned higher. Asilisaurus has fewer teeth in the dentary (8-10) than other silesaurids, and the tooth row occupies a smaller portion of the bone than its relatives. The rear of the lower jaw is similar to other silesaurids, with a long retroarticular process and weakly defined surangular ridge. The middle portion of the lower jaw is not known, so there is ambiguity about the overall shape of the jaw.[1][2]

Postcranial skeleton

The neck vertebrae are parallelogram-shaped and moderately elongated, proportionally similar to other silesaurids. Most of the depressions and ridges on the neck vertebrae of Asilisaurus were not as well-developed as those of Silesaurus. However, the postzygapophyses of a few vertebrae do have small projections identified as epipophyses, which are present in aphanosaurs and dinosaurs but not advanced silesaurids. The dorsal vertebrae are shorter and more complex, lacking epipophyses and instead possessing hyposphenes, another dinosaur-like feature. There were two sacral vertebrae, each with its own sacral ribs. This contrasts with Silesaurus, which has three or four sacral vertebrae which share sacral ribs between each other. Like other dinosauriforms, the tail vertebrae increase in length further down the tail.[1][2]

The scapula is long and narrow, expanded into a triangular structure at the tip and lacking any perforations on the acromion process. The glenoid is directed backwards, and overlies a strongly developed knob-like process on the coracoid. The shaft of the humerus is straight and only slightly twisted. Several aspects of the humerus, such as the small deltopectoral crest connected to the humeral head by a thick ridge, do not resemble the situation in dinosaurs. Many of the joint surfaces at the shoulder and elbow are roughly textured and well-delineated. The radius is thin and simple, similar in shape to that of Herrerasaurus. However, it was also shorter than the humerus, only about 85% the length of that bone. The ulna is similar and has a large olecranon process and an autapomorphic broad groove running down along its outer edge. The hand is poorly known, but the best preserved metacarpal (probably a second metacarpal) is small, indicating that the hand was likely much shorter than the foot.[1][2]

Asilisaurus's hip had a closed acetabulum, rather than the open acetabulum of dinosaurs. The postacetabular process of the ilium possessed a brevis fossa (only visible from below) edged by subtle medial and lateral ridges, with the lateral ridge likely homologous to the brevis shelf of dinosaurs. The preacetabular process, on the other hand, was edged by a lateral ridge similar to that of other silesaurids. The ischium is generally similar to Sacisaurus and other dinosauromorphs, with connected shafts separated by a groove on the top. A small expansion is present at the tip of the ischium. The pubis is also similar to that of Sacisaurus, with a long shaft topped by a short crest. There is a small gap at the intersection of the ilium, ichium, and pubis.[1][2]

The upper portion of the femur possesses many of the features typical for dinosauriforms. These include a groove on the top of the femoral head, a facies articularis antitrochanterica, three equally well-developed proximal tubera, and an anterior trochanter and trochanteric shelf. It lacks certain adaptations of more advanced silesaurids, such as a straight medial edge of the femoral head. The dorsolateral trochanter is poorly developed, in contrast to many dinosaurs. Much of the lower portion of the femur is also weakly developed, with the exception of a groove on the rear edge of the bone, which is extended up the shaft to the same extent as most other silesaurids. The tibia is also par for the course for dinosauriforms, with a straight cnemial crest, two equally sized proximal condyles, and a lateral groove in the distal portion. This is furthermore the case with the fibula, which closely resembles that of Teleocrater and Saturnalia. The tibia and fibula are shorter than the femur, unlike basal dinosaurs. Asilisaurus retains a "primitive" crurotarsal ("crocodile-normal") ankle characterized by a convex-concave interaction between the astragalus and calcaneum. The calcaneum is fairly similar to that of Teleocrater. It has a convex fibular joint separated from a small but distinct calcaneal tuber. The astragalus is similar to that of Marasuchus and has a low and ridge-like ascending process. In some respects the fourth distal tarsal resembles that of Lagerpeton, but in other respects (such as the large facet for metatarsal V) it is clearly different. The foot is shorter than that of other silesaurids but still rather long, with the third metatarsal being the longest bone (at just under half the length of the tibia), followed by the second and fourth which are about the same length at each other. Overall the foot is similar to that of Saturnalia, with some exceptions. Unlike many dinosauromorphs, the fifth metatarsal is not vestigial and instead is a fairly thick bone slightly longer than the thin first metatarsal, which is also not too short. All of the metatarsals had accompanying phalanges, though complete toes are not known. Unguals were low and wide, a "hoof"-like appearance also seen in Silesaurus and the unrelated shuvosaurids.[1][2]

Paleobiology

Diet

Evidence for a beak at the tip of the snout and peg-like teeth further back support the idea that Asilisaurus was an omnivore or herbivore. These traits are mirrored by dinosaurs which acquired a herbivorous diet, such as ornithischians and advanced sauropodomorphs.[1][3] The conical shape of the teeth shares some similarities with piscivorous reptiles such as spinosaurids and crocodilians, leading to the possibility that fish were part of its diet.[5] The teeth are similar to those of Silesaurus, which has been considered a primarily herbivorous browser based on dental microwear,[6] or an insectivore based on referred coprolites.[7] Regardless, Asilisaurus was very unlikely to be a specialized carnivore like the more basal silesaurid Lewisuchus, nor an obligate herbivore like Kwanasaurus.[8]

Development

Femora assigned to Asilisaurus seem to exhibit both "slender" and "robust" morphologies. On average, "robust" femurs are larger and have more prominent bone scars. Many other dinosauriforms are known to possess these different morphologies, such as coelophysids, Masiakasaurus, and Silesaurus. This variation has traditionally (but perhaps incorrectly) been interpreted as sexual dimorphism. In a 2016 study, a sample of 27 Asilisaurus femurs were analyzed to determine how they developed. The study attempted to determine the sequence through which 11 femoral traits (mostly muscle scars) appeared in the bone. The study found that there was no universal sequence, and instead multiple polymorphic trajectories, with many traits appearing earlier in the sequence in some bones and later in others. This large amount of variability is also observed in dinosaurs, but not Dromomeron or Silesaurus (although these may be due to a small sample size). There are some general trends, such as the anterior trochanter and linea intermuscularis cranialis appearing early, and the fourth trochanter transitioning to a wide and rounded shape late in development.[9]

There is only a weak relationship between skeletal maturity and size, as some small "robust" femora are more well-developed than some large "slender" ones. In most cases there is no correlation between the presence of absence of different traits. More consistency over the presence or absence of traits would be expected if the different morphologies were truly based on sexual dimorphism. However, this is not the case since no bimodality is observed. The size and developmental variation of Asilisaurus suggests that "robust" morphologies are simply more mature individuals, while "slender" morphologies are less mature individuals. Large "slender" femora can be explained as coming from young Asilisaurus which were able to increase in size by taking advantage of plentiful resources, but had not yet attained skeletal maturity. Small "robust" femora are a result of the opposite circumstance, belonging to mature Asilisaurus which grew up in more impoverished environments. This type of "developmental plasticity" has previously been proposed for Plateosaurus, some "pelycosaurs" (basal synapsids), and observed in modern Alligator mississippiensis. The large amount of variability in Asilisaurus' sequence of muscle scar development is likely a matter of individual variation. Since dinosaurs experience the same variability, sexual dimorphism is unlikely to be responsible for their different femoral morphologies.[9] The study also involved histological analysis on the femur, humerus, tibia, and fibula. No LAGs (lines of arrested growth) are observed, even in bones from large individuals. The cross-sections are very similar to those of Silesaurus and coelophysids, with a woven-fibered cortex full of longitudinal canals. The bone fibers are not well organized, but many are oriented parallel to the circumference of the bone. This is intermediate between crocodilians (which have discrete layers of slowly-growing bone), and dinosaurs (in which there is completely disorganized fast-growing bone). Osteocyte lacunae are abundant, as with other dinosauromorphs. Some of the longitudinal canals branch into irregular forms (in cross section) near the surface of the bone, to a greater extent than Silesaurus but a lesser extent than coelophysids. Increasing size, abundance, and branching of canals is correlated with higher growth rates. Asilisaurus is close to, but not as developed as dinosaurs in these regards as well. It is hypothesized that a lack of LAGs is not indicative that all the specimens died within a year, as the estimated growth rate is not fast enough to achieve skeletal maturity within that time period. Instead, Asilisaurus may have had a constant and moderately high growth rate (though slower than dinosaurs), which was not impeded by any seasonal interruptions.[9]

References

- Nesbitt, S.J.; Sidor, C.A.; Irmis, R.B.; Angielczyk, K.D.; Smith, R.M.H.; Tsuji, L.A. (2010). "Ecologically distinct dinosaurian sister group shows early diversification of Ornithodira". Nature. 464 (7285): 95–98. doi:10.1038/nature08718. PMID 20203608.

- Nesbitt, S.J.; Langer, M.C.; Ezcurra, M.D. (2019). "The Anatomy of Asilisaurus kongwe, a Dinosauriform from the Lifua Member of the Manda Beds (~Middle Triassic) of Africa". The Anatomical Record. 303 (4): 813–873. doi:10.1002/ar.24287. PMID 31797580.

- "Oldest known dinosaur relative discovered". ScienceDaily. March 3, 2010. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- Barrett, Paul M.; Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Peecook, Brandon R. (2015-04-01). "A large-bodied silesaurid from the Lifua Member of the Manda beds (Middle Triassic) of Tanzania and its implications for body-size evolution in Dinosauromorpha". Gondwana Research. 27 (3): 925–931. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2013.12.015. ISSN 1342-937X.

- Hoffman, Devin K.; Edwards, Hunter R.; Barrett, Paul M.; Nesbitt, Sterling J. (2019-11-05). "Reconstructing the archosaur radiation using a Middle Triassic archosauriform tooth assemblage from Tanzania". PeerJ. 7: e7970. doi:10.7717/peerj.7970. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6839518. PMID 31720109.

- Kubo, Tai; Kubo, Mugino O. (June 2013). "Dental microwear of a Late Triassic dinosauriform, Silesaurus opolensis" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 59 (2): 305–312. doi:10.4202/app.2013.0027. ISSN 0567-7920.

- Qvarnström, Martin; Wernström, Joel Vikberg; Piechowski, Rafał; Tałanda, Mateusz; Ahlberg, Per E.; Niedźwiedzki, Grzegorz (2019). "Beetle-bearing coprolites possibly reveal the diet of a Late Triassic dinosauriform". Royal Society Open Science. 6 (3): 181042. doi:10.1098/rsos.181042. PMC 6458417. PMID 31031991.

- Martz, Jeffrey W.; Small, Bryan J. (2019-09-03). "Non-dinosaurian dinosauromorphs from the Chinle Formation (Upper Triassic) of the Eagle Basin, northern Colorado: Dromomeron romeri (Lagerpetidae) and a new taxon, Kwanasaurus williamparkeri (Silesauridae)". PeerJ. 7: e7551. doi:10.7717/peerj.7551. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6730537. PMID 31534843.

- Griffin, C. T.; Nesbitt, Sterling J. (2016-03-04). "The femoral ontogeny and long bone histology of the Middle Triassic (?late Anisian) dinosauriform Asilisaurus kongwe and implications for the growth of early dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (3): e1111224. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1111224. ISSN 0272-4634.