Redondasaurus

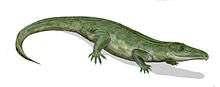

Redondasaurus is an extinct genus of phytosaur from the Late Triassic (230-200 million years ago) of the southwestern United States. It was named by Hunt & Lucas in 1993, and contains two species, R. gregorii and R. bermani. It is the youngest and most evolutionarily-advanced of the phytosaurs.

| Redondasaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton of Redondasaurus bermani at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Phytosauria |

| Family: | †Phytosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Pseudopalatinae |

| Genus: | †Redondasaurus Hunt & Lucas, 1993 |

| Species | |

| |

Description

Redondasaurus, like other phytosaurs, had a very long snout. Known skull lengths range from 22 cm (0.72 ft) in juveniles to 120.5 cm (3.95 ft) in very large adults,[1] suggesting total lengths up to 6.4 m (21 ft).[2] The enamel in the teeth of Redondasaurus has a columnar microstructure.[3]

R. gregorii: Differs from other Redondasaurus species in that it lacks a rostral crest. Complete skulls of this species are uncommon, but some fragmentary narrow-snouted phytosaur specimens from the Redonda Formation may be part of the taxon.[4]:331

R. bermani: Differs from other Redondasaurus species in that it has a rostrum with a partial crest. Only one skull of this species has been found, but Hunt and Lucas postulate that "by analogy with other phytosaurs, it is likely that this crested species was sub-equal in abundance with [R. gregorii].".[4]:331

History of discovery

The first specimen now described with genus Redondasaurus was found in 1939 by D.E. Savage in the Travesser Formation in New Mexico. Savage originally described this find as Machaeroprosopus.[4] The 1947 discovery of another phytosaur skull in the Redonda Formation, New Mexico, by E.H. Colbert and J.T. Gregory led to the first recognition that both skulls represented a new taxon. In addition, they proposed that the skulls represented the most derived phytosaur in North America due to their supratemporal fenestrae being hidden in dorsal view.[4]< A third skull was discovered by D.S. Berman in the 1980s and was later identified as Pseudopalatus buceros.[4]

Genus Redondasaurus was first named by A.P. Hunt and S.G. Lucas in "A New Phytosaur (Reptilia: Archosauria) Genus from the Uppermost Triassic of the Western United States and Its Biochronological Significance," published in the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science Bulletin in 1993. The authors had previously included the unnamed phytosaur species in a 1992 paper on "Triassic Stratigraphy and Paleontology" in New Mexico.[5]

The genus name Redondasaurus is derived from the its location of discovery (Mesa Redonda near Tucumcari, New Mexico).[4][2]

Classification

The diagnostic criteria given in 1993 for the new genus was as follows:

"Phytosaurid that differs from other genera in possessing supratemporal fenestrae that are essentially concealed in dorsal view and whose anterior margin only slightly emarginates the skull roof and has wide squamosal-postorbital bars.":331

Hunt and Lucas also extended Colbert and Gregory's analysis that Redondasaurus was the most derived North American phytosaurs, as:

"Phytosaurs show an evolutionary trend to displace ventrally the posterior portion of the midline of the skull roof. Redondasaurus represents the most advanced development of this character.":331

Additional diagnostic criteria were introduced in 2012 by J. Spielmann and S.G. Lucas.[6][7] These include:

- Reduced antorbital fenestra

- A prominent pre-infratemporal shelf

- A septomaxilla forming the anterolateral half of the external naris

- Thickened rim of the orbit

- Inflated posterior part of nasal

- Thickened dorsal osteoderms

Historically, studies of Redondasaurus have been hampered by small number of specimens available, of which only four skulls were recognized in literature. Recently, several Norian-Rhaetian phytosaur skulls have been referred to Redondasaurus, which has brought the number of recognized skulls to ten. These new specimens encompass a range of sizes from hatchlings to adults and possibly include the first evidence of sexual dimorphism in the taxon.[7]

Sexual dimorphism within Redondasaurus was also recognized by J. Spielman and S.G. Lucas on May 11, 2012, at the 64th Annual Meeting of the Geological Society of America.[8]

Disagreement on the validity of Redondasaurus emerged 1995, when Long and Murry did not accept it and referred to the specimen as Pseudopalatus pristinus instead. The reason for this may have been that the type specimen of Redondasaurus is missing the entire narial area, left side of its snout, the anterior two thirds of the right premaxilla, and most of its palate.[6] In addition to this, the term used by Savage to describe the first specimen found in 1939,[4] Machaeroprosopus, continues to be used by some scholars in place of Redondasaurus as the genus name.[6] Hungerbühler et al. argued in 2013 that Redondasaurus should be regarded as a junior synonym of Machaeroprosopus because:

- Upon a comparison of cranial characters, Machaeroprosopus lottorum is found to bridge the morphological gap between Redondasaurus and Machaeroprosopus in such a way that the distinction becomes arbitrary.

- According to cladistic analysis, it us unlikely that Redondasaurus is in a basal position compared to other North American pseudopalatine phytosaurs.

- For R. gregorii and R. bermani to be sister taxa, three additional steps would be necessary for forming a phylogenetic tree. This is the case even if the rostral crest, used by Lucas and Hunt to differentiate R. gregorii and R. bermani, is ignored in the analysis.[6]

Paleoecology

The Chinle Group, where a large portion of Redondasaurus skulls have been found, is composed of fluvial and lacustrine sediments. Accumulations of fossils in the Chinle Formation can be found in floodplains, bogs, ponds, and fluvial channels. Additional paleontological and sedimentary evidence support the hypothesis that the climate of the Chinle was strongly influenced by high levels of precipitation.[9]

Redondasaurus has been collected five times in New Mexico and once in Utah, USA. Specifically, they have been found in the Rock Point Formation (part of Chinle Group), Travesser Formation, and Redonda Formation in New Mexico.[5] The Chinle group is particularly important to paleontologists interested in aeutosaurs, as it has been critical in establishing their biochronology in the Late Triassic.[10] Redondasaurus has also been found in the Wingate Sandstone Formation in Utah.[11] The following collections are according to location and date of discovery.

New Mexico, USA

1) Upper Travesser Formation - Union County, New Mexico[12]

- • Age: Norian (221.5 - 205.6 million years ago.)

- • Collected by: D.E. Savage.

- • Date of Collection: 1939.

- • Environment/lithology: "soft purple-maroon shale".

2) Chinle Formation - Rio Arriba County, New Mexico [13]

3) Redonda Formation - Quay County, New Mexico [14]

- • Age: Norian (221.5 - 205.6 million years ago.)

- • Collected by: P. Murry, A. Hunt, and S. Lucas.

- • Date of Collection: 1981, 1986-87.

- • Environment/lithology: "floodplain", red siltstone.

4) Redonda Formation - Quay County, New Mexico [15]

- • Age: Norian (221.5 - 205.6 million years ago.)

- • Collected by: P. Murry.

- • Date of Collection: 1989.

- • Environment/lithology: "terrestrial", green-grey siltstone and red claystone.

5) Redonda Formation - Quay County, New Mexico [16]

- • Age: Norian (221.5 - 205.6 million years ago.)

- • Collected by: P. Sealey.

- • Date of Collection: 2001.

- • Environment/lithology: "channel lag", conglomerate and bentonitic mudstone.

Utah, USA

1) Wingate Sandstone Formation - San Juan County, Utah [17]

- • Age: Rhaetian (205.6 - 201.6 million years ago.)

- • Collected by: not given.

- • Date of Collection: not given.

- • Environment/lithology: "fluvial", intraclastic sandstone and conglomerate.

Redondasaurus is important because it serves as an index species for the Apachean Land Vertebrate Faunachron (LVF). Indeed, it is considered a true index fossil because Redondasaurus is temporally restricted and easily identified.[18] The biostratigraphic importance of the genus was reaffirmed when it was determined that the beginning of the Apachean was lower than previously concluded. Rather than at the base of the Redonda Formation, the Apachean appears high in the Bull Canyon Formation. Correlating the vertebrate stratigraphy of Redondasaurus has also allowed for the correlation of Redonda locally within the southwestern USA.[8] Given the recent acquisition of additional diagnostic characteristics, and the increase in number of Redondasaurus skulls recognized in literature, it is likely that the use of the genus as an index fossil will expand to other deposits and even globally.[7]

References

- Lucas, Spencer G.; Spielmann, Justin A.; Rinehart, Larry F. (2013). "Juvenile skull of the phytosaur Redondasaurus from the Upper Triassic of New Mexico, and phytosaur ontogeny". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin. 61.

- "Redondasaurus". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. Archived from the original on December 20, 2015. Retrieved 2015-03-01.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "Tooth Enamel Microstructure of Selected Archosaurs Reptilia: Archosauria from the Upper Triassic Chinle Group, Western USA: Taxonomic and Evolutionary Significance". Andrew B. Heckert and Jessica Camp; Dept. of Geology, Appalachian State University. 2007-10-31. Archived from the original on 2011-06-08. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- Hunt, Andrian P.; Lucas, Spencer G. (1993). "A new phytosaur (Reptilia: Archosauria) genus from the Uppermost Triassic of the Western United States and its biochronological significance". New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science Bulletin. 3.

- Lucas, SPENCER G., and ADRIAN P. Hunt. "Triassic stratigraphy and paleontology, Chama basin and adjacent areas, north-central New Mexico." New Mexico Geological Society Guidebook 43 (1992): 151-167.

- Hungerbühler, Axel; Mueller, Bill; Chatterjee, Sankar; Cunningham, Douglas P. (September 2012). "Cranial anatomy of the Late Triassic phytosaur Machaeroprosopus, with the description of a new species from West Texas". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 103 (3–4): 269–312. doi:10.1017/S1755691013000364. ISSN 1755-6929.

- "REVISION OF REDONDASAURUS GREGORII (ARCHOSAURIA: PARASUCHIDAE) FROM THE LATE TRIASSIC (NORIAN-RHAETIAN) OF NEW MEXICO". Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- "REVISION OF THE REDONDA FORMATION (UPPER TRIASSIC CHINLE GROUP) VERTEBRATE FAUNA AND ITS IMPACT ON THE APACHEAN LAND-VERTEBRATE FAUNACHRON". Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- Michael Parrish, J. (1989). "Vertebrate paleoecology of the Chinle formation (Late Triassic) of the Southwestern United States". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. XIIth INQUA Congress. 72: 227–247. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(89)90144-2. ISSN 0031-0182.

- Lucas, Spencer G.; Heckert, Andrew B. (1996). "Late Triassic aetosaur biochronology" (PDF). Albertiana. 17: 57–64. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-13. Retrieved 2015-03-06.

- "Redondasaurus". Retrieved 2015-03-06.

- "Fossilworks: Gateway to the Paleobiology Database". Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- "Fossilworks: Gateway to the Paleobiology Database". Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- "Fossilworks: Gateway to the Paleobiology Database". Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- "Fossilworks: Gateway to the Paleobiology Database". Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- "Fossilworks: Gateway to the Paleobiology Database". Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- "Fossilworks: Gateway to the Paleobiology Database". Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- Lucas, Spencer G (November 1998). "Global Triassic tetrapod biostratigraphy and biochronology". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 143 (4): 347–384. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.572.872. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(98)00117-5. ISSN 0031-0182.

Further reading

- The Great Rift Valleys of Pangea in Eastern North America By Peter M. LeTourneau, Paul Eric Olsen. Published 2003, Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12676-X

- Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology By Elsevier Science (Firm) Published 1998, Elsevier. v. 143. Original from the University of California.