Palm Beach, Florida

Palm Beach is an incorporated town in Palm Beach County, Florida, United States. Located on an island in east-central Palm Beach County, the town is separated from several nearby cities including West Palm Beach and Lake Worth Beach by the Intracoastal Waterway to its west, though Palm Beach borders a small section of the latter and South Palm Beach at its southern boundaries. As of 2010 census, Palm Beach had a year-round population of 8,348 and an estimated population of 8,816 in 2019, with an increase to approximately 25,000 people between November and April.

Palm Beach, Florida | |

|---|---|

| Town of Palm Beach | |

Palm Beach proper in 2011 | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): "The Island" | |

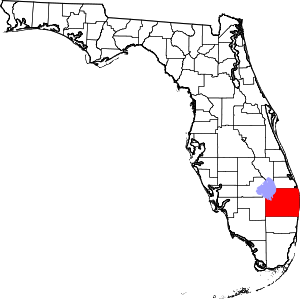

Palm Beach, Florida  Palm Beach, Florida | |

| Coordinates: 26°42′54″N 80°02′22″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Settled (Lake Worth Settlement) | c. 1872[1][2] |

| Settled (Palm Beach Settlement) | January 9, 1878[3][4] |

| Incorporated (Town of Palm Beach) | April 17, 1911[2] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Gail L. Coniglio |

| • Council President | Margaret A. Zeidman[5] |

| • Town manager | Kirk Blouin |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7.80 sq mi (20.20 km2) |

| • Land | 3.80 sq mi (9.84 km2) |

| • Water | 4.00 sq mi (10.36 km2) |

| Elevation | 7 ft (2 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 8,348 |

| • Estimate (2019)[7] | 8,816 |

| • Density | 2,319.39/sq mi (895.51/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 33480 |

| Area code(s) | 561 |

| FIPS code | 12-54025[8] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0288390[8] |

| Website | townofpalmbeach |

Settlers began arriving in modern-day Palm Beach as early as 1872 and opened a post office about five years later. Elisha Newton "Cap" Dimick, later the town's first mayor, established Palm Beach's first hotel, the Cocoanut Grove House, in 1880. However, it was Standard Oil tycoon Henry Flagler who became instrumental in transforming the island of jungles and swamps into a winter resort for the wealthy. Flagler and his workers constructed the Royal Poinciana Hotel in 1894, The Breakers in 1896, and Whitehall in 1902; extended the Florida East Coast Railway southward to the area by 1894; and developed a separate city to house hotel workers, which later became West Palm Beach. The town of Palm Beach officially incorporated on April 17, 1911. Addison Mizner also contributed significantly to the town's history, designing 67 structures, including El Mirasol, the Everglades Club, La Querida, the William Gray Warden House, and Via Mizner, which is a section of Worth Avenue.

Forbes reported in 2017 that Palm Beach had at least 30 billionaires, with the town ranking as the 27th-wealthiest place in the United States in 2016 according to Bloomberg News. Many famous and wealthy individuals have resided in the town, including United States presidents John F. Kennedy and Donald Trump. Palm Beach is also noted for upscale shopping districts such as Worth Avenue, Royal Poinciana Plaza, and the Royal Poinciana Way Historic District.

History

Settlers began arriving in modern-day Palm Beach by 1872.[4] Hiram F. Hammon made the first homestead claim in 1873 along Lake Worth. At the time, the lake area had a population of less than 12 people. By 1877, the Tustenegee Post Office was established in modern-day Palm Beach, becoming the lake area's first post office.[1] Along the coast of Palm Beach, the Providencia wrecked in 1878 with a cargo of 20,000 coconuts, which were quickly planted.[4] In 1880, Elisha Newton "Cap" Dimick converted his private residence to a hotel known as the Cocoanut Grove House. At the time of its opening, the Cocoanut Grove House was the only hotel along Florida's east coast between Titusville and Key West. The hotel would be destroyed by a fire in October 1893.[9] The Star Route, also known as the Barefoot mailman route, began serving the area in 1885.[10] Carriers would deliver mail by foot or boat from Palm Beach and other nearby communities to as far south as Miami, a round trip distance of 136 miles (219 km).[11] The first schoolhouse in southeast Florida (also known as the Little Red Schoolhouse) opened in Palm Beach in 1886.[10]

Henry Flagler, a Standard Oil tycoon, made his first visit to Palm Beach in 1893 and described the area as a "veritable paradise."[12] That same year, Flagler hired George W. Potter to plot 48-blocks for West Palm Beach – a city to house workers at his hotels – and construction began on the Royal Poinciana Hotel.[13][14] The Royal Poinciana Hotel opened for business on February 11, 1894.[13] Flagler, also owner of the Florida East Coast Railway, extended the railroad southward to West Palm Beach by the following month.[15] In 1896, Flagler opened a second hotel originally known as Wayside Inn, before being renamed Palm Beach Inn, and later becoming The Breakers.[16] Fires would later burn down the hotel in 1903 and 1925, but it would be rebuilt twice. The Palm Beach Daily News began publication in 1897 originally under the name Daily Lake Worth News.[17]

The first pedestrian bridge across the Intracoastal Waterway opened near the modern-day Flagler Bridge in 1901, replacing the original railroad spur.[17] Flagler's house lots were bought by the beneficiaries of the Gilded Age,[15] and in 1902 Flagler himself built a Beaux-Arts mansion, Whitehall, designed by the New York-based firm Carrère and Hastings and helped establish the Palm Beach "winter season".[18] Telephone service was established in Palm Beach in 1908, with 18 customers initially.[19] Prior to the 1910s, many African Americans in the area lived in a segregated section of Palm Beach called the "Styx",[20] with an estimated population of 2,000 at its peak. However, between 1910 and 1912, African Americans were evicted from the Styx.[21] Most of the displaced residents relocated to the northern West Palm Beach neighborhoods of Freshwater, Northwest, and Pleasant City.[20]

.jpg)

In January 1911, it became known that West Palm Beach intended to annex the island of Palm Beach in the upcoming Florida Legislative session. Residents objected and hired an attorney from Miami to officially become incorporated.[22] Dimick, Louis Semple Clarke, and 31 other male property owners congregated at Clarke's house and signed a charter to officially incorporate the town of Palm Beach on April 17, 1911.[23] Dimick became the first mayor, John McKenna became town clerk, and Joseph Borman became town marshal, while J. B. Donnelly, William Fremd, John Doe, Enoch Root, and J.J. Ryman served as the first council members.[22] Also in 1911, Dimick built the Royal Park Bridge, with its first incarnation being a wooden structure. Passage from West Palm Beach to Palm Beach on the bridge originally required a toll – 25 cents per vehicle and 5 cents per pedestrian.[23]

Between 1919 and 1924,[24] American resort architect Addison Mizner designed 67 structures in Palm Beach.[25] Some of Mizner's clients included Anthony Joseph Drexel Biddle Jr., Paul Moore Sr., Gurnee Munn, John Shaffer Phipps, Edward Shearson, Eva Stotesbury. Rodman Wanamaker, and Barclay Harding Warburton II.[24] His designed works included the Costa Bella,[26]:212 El Mirasol, Everglades Club (in collaboration with Paris Singer),[25] El Solano,[27] La Bellucia,[26] La Querida,[25] Via Mizner,[26]:238 Villa Flora,[26]:103 and William Gray Warden House.[27]:236 Via Mizner was the first shopping complex along Worth Avenue, which was then a mostly residential street.[28] In February 1924, the town council allotted $100,000 toward construction of a new municipal building. Harvey and Clarke architectural firm designed the building, while Newlon and Stephens constructed the structure after bidding $160,200 for the contract. The Palm Beach Town Hall opened on December 18, 1925, and is still used for town council meetings. Prior to its completion, the council meetings were held in one story wooden building on Royal Poinciana Way.[29] Also in 1925, citywide construction revenue reached $14 million, attributed to Florida land boom.[17] The 1928 Okeechobee hurricane made landfall in the town of Palm Beach with sustained winds of 145 mph (235 km/h).[30] High winds and storm surge caused damage to 610 businesses, 60 homes, and 10 hotels, as well as to the Public Service Corporation and Ocean Boulevard. Damage in 1928 USD totaled $10 million in Palm Beach.[31]

.jpg)

The population of Palm Beach grew from 1,707 in 1930 to 3,747 in 1940, a 119.5 percent increase. The Royal Poinciana Hotel, damaged heavily in the 1928 hurricane, also suffered greatly during the Great Depression, and was demolished in 1935. Around 4,000 people purchased the salvageable remains of the hotel. The Palm Beach-Post Times estimated that some 500 homes could be built from the scraps of the hotel.[32] Residents of Palm Beach established the Society of the Four Arts on January 14, 1936, with Hugh Dillman becoming the first president.[33] The 1930s decade also saw the construction of the Flagler Memorial Bridge, the northernmost bridge linking Palm Beach and West Palm Beach, completed on July 1, 1938.[34] Palm Beach mayor James M. Owens acted as master of ceremonies for the bridge's opening, while then-U.S. senator Charles O. Andrews and former U.S. senator Scott Loftin gave speeches during the event.[35]

Early in World War II, the United States Army established a Ranger camp at the northern tip of the island, which could accommodate 200 men.[36] The Palm Beach Civilian Defense Council ordered blackouts in Palm Beach beginning on April 11, 1942.[37] Throughout the war, German U-boats sank twenty-four ships offshore Florida, with eight capsized offshore Palm Beach County between February and May 1942.[38] The Army converted The Breakers into the Ream General Army Hospital, while the Navy converted the Palm Beach Biltmore Hotel into a U.S. Naval Special Hospital.[36] On September 15, 1950, the Southern Boulevard Bridge opened,[33] the third and southernmost bridge linking Palm Beach and West Palm Beach.[39] Residents of Palm Beach elected Claude Dimick Reese (son of former mayor T.T. Reese and grandson of Dimick) as mayor in 1953. He became the only native-born mayor of Palm Beach in its history. In the 1950s, the town's population grew approximately 55.8%, from 3,866 in 1950 to 6,055 in 1960.[33]

.jpg)

John F. Kennedy was elected President of the United States in 1960 and selected La Querida as his Winter White House,[33] which his father bought in 1933.[25] In December 1960, police in Palm Beach averted a retired postal worker's attempt to assassinate then president-elect Kennedy. The president would also spend the last weekend of his life in Palm Beach, several days before his assassination in November 1963. Yvelyne "Deedy" Marix became the first woman elected to the town council in February 1970 and later became the first woman elected mayor of Palm Beach in 1983.[33] Between 1971 and 1977, Earl E.T. Smith served as mayor of Palm Beach. He was previously an Ambassador of the United States to Cuba.[19] Preservationist Barbara Hoffstot published a book titled "Landmark Architecture in Palm Beach" in 1974. She personally photographed and summarized many older buildings in the town. The book also called for more awareness of and improvements to a system for protecting historic landmarks.[40] The town council responded in 1979 by approving an ordinance establishing the Landmarks Preservation Commission, which identifies and works to protect historic structures.[41]

General Foods and Post Cereals heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post bequeathed Mar-a-Lago to the United States upon her death in 1973,[42] hoping it would be used as a Winter White House.[43] The residence would be returned to the Post family in 1981, before being purchased by then-businessman Donald Trump in 1985 for approximately $10 million.[44] He would convert the estate into a club by 1995 and has used Mar-a-Lago as a Winter White House since the beginning of his presidency in 2017.[42][45] A nor'easter in November 1984 caused the MV Mercedes I to crash into the seawall of Mollie Wilmot's estate.[33] Wilmot's staff served the 10 sailors sandwiches and freshly brewed coffee in her gazebo and offered martinis to journalists reporting on the incident.[46]

On October 31, 1991, the Perfect Storm produced waves 20 feet (6.1 m) in height in Palm Beach. About 1,200 feet (370 m) of seawall at Worth Avenue was destroyed, while some parts of the town experienced coastal flooding, especially along Ocean Boulevard.[47] By that afternoon, police allowed only residents to enter the town.[33] The trial of William Kennedy Smith, a member of the Kennedy family, drew international media attention in 1991. Smith had been accused of committing rape at La Querida, but a trial at the Palm Beach County Court resulted in his acquittal on December 11, 1991. Another notable mayor, Paul Ilyinsky, son of Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia and heiress Audrey Emery, was elected to the office in February 1993.[33] The town's population peaked at 10,468 people in the 2000 census.[48] In March 2005, the Palm Beach Police Department – under the guidance of Police Chief Michael Reiter – began the first inquiry into the crimes committed by infamous sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein, leading to his arrest and indictment in July 2006. Despite an FBI investigation discovering at least 40 victims, the State Attorney of Palm Beach County would only charge Epstein with soliciting a prostitute and soliciting a minor for prostitution in June 2008. He plead guilty on both counts and received a controversial plea deal.[49]

The town had a population of 8,348 people in 2010, a decrease of 20.3 percent from the previous census.[48] Palm Beach celebrated its centennial on April 17, 2011. Approximately 1,200 people attended a parade, with the parade route beginning at the Flagler Museum (Whitehall).[50] Between February and December 2015, the Town Square, which includes the Addison Mizner Memorial Fountain and the town hall, underwent a $5.7 million restoration. The fountain's restoration would be named "project of the year" by the American Public Works Association's Florida chapter.[51]

Name

The January 1878 wreck of the Providencia is credited with giving Palm Beach its name. The Providencia was traveling from Havana to Cádiz, Spain, with a cargo of coconuts harvested in the Crown Colony of Trinidad and Tobago in the British West Indies, when the ship wrecked near Palm Beach. Many of the coconut naturalized or were planted along the Palm Beach coast.[3][52] A lush grove of palm trees soon grew on what would later be named Palm Beach.[4]

Geography

Palm Beach is one of the easternmost towns in Florida, though the state's easternmost point is located in Palm Beach Shores, just north of Lake Worth Inlet.[53] The town is located on an 18-mile (29 km) long barrier island between the Intracoastal Waterway (locally known as the Lake Worth Lagoon) on the west and the Atlantic Ocean on the east. At no point is the island wider than three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km), and in places it is only 500 feet (150 m) wide.[54] The northern boundary of Palm Beach is the Lake Worth Inlet, though it adjoined with Singer Island until the permanent dredging of the inlet in 1918.[55] To the south, a section of Lake Worth Beach occupies the island in the vicinity of State Road 802, though an exclave of Palm Beach extends farther southward until the northern limits of South Palm Beach.[56] According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the town has a total area of approximately 8.12 sq mi (21.0 km2), with land accounting for approximately 4.20 sq mi (10.9 km2) and water covering the remaining 3.92 sq mi (10.2 km2).[57] The average elevation of the town is 7 ft (2.1 m);[8] the highest point is 30 ft (9.1 m) above sea level on the golf course at the Palm Beach Country Club.[58]:IX-4

Geologically, the island is a sand-covered ridge of coquina rock.[58]:I-7 In the pre-settlement period, the island was environmentally characterized with a pronounced coastal ridge bordering the Atlantic Ocean. The Intracoastal Waterway coast was primarily low-lying and swampy; marshly sloughs generally lay between the two features,[58]:IX-4 though an oolitic limestone ridge stood along some parts of the island's westward side. Since 1883, the environment has been significantly altered by developing land, the filling of the sloughs, and a receding coastline due to erosion. However, the Atlantic ridge is still the dominating topographical feature of the island and acts as a seaward barrier. The former slough areas are flood prone.[58]:I-8

The town and entire barrier island are located within Evacuation Zone B and evacuations are often ordered if a hurricane is forecast to impact the area, mostly recently in anticipation of Hurricane Dorian in 2019.[59] Palm Beach town officials may deploy law enforcement officers to strategically place roadblocks to limit access to the island during unsafe conditions.[60]

As of 2016, land use of the town is 60% residential, 13% rights-of-way, 10% private group uses, 3% recreational, 3% commercial, 2% public uses, 1% hotels (not including The Breakers), and less than 1% conservation, while The Breakers is a planned unit development accounting for 6% of land use. The remaining 2% of land was vacant.[58]:I-9 Palm Beach does not have any land dedicated to agricultural or industrial purposes. The town is essentially built-out and cannot extend its boundaries.[58]:I-11

Conservation is mainly confined to Bingham Island, Fishermen's Island, and Hunter's Island. Functioning as bird sanctuaries and rookeries, the islands are leased by the National Audubon Society, though State Trustees of the Internal Improvement Fund and the Blossom Estate holds the titles to the islands. A part of Blossom Estate Subdivision just south of Southern Boulevard is also designated a conservation area.[58]:I-11

Climate

According to the Köppen climate classification, Palm Beach has a tropical savanna climate with hot, humid summers and warm, dry winters. The annual average precipitation is 62.3 in (1,580 mm), most of which occurs during the summer season from May through October.[61] In the wet summer season, short-lived heavy afternoon thunderstorms are common.[62] Palm Beach reports more than 2,900 hours of sunshine annually. Although tropical cyclones can impact Palm Beach, strikes are rare, with the last direct hit in 1928.[61][63]

The wet season is from May to October, when convective thunderstorms and downpours are common.[62] Average high temperatures in Palm Beach are 83 to 91 °F (28 to 33 °C) with lows of 68 to 76 °F (20 to 24 °C),[64] though low temperatures at or above 80 °F (27 °C) are not uncommon.[65] During this period, more than half of the summer days bring occasional afternoon thunderstorms and seabreezes that somewhat cool the rest of the day. The winter brings dry, sunny, and much less humid weather.[62] Between December and February, average high temperatures range from 74 to 82 °F (23 to 28 °C) and low temperatures average between 57 and 68 °F (14 and 20 °C).[64] High temperatures occasionally drop below 70 °F (21 °C), while at other times highs occasionally reach 90 °F (32 °C) in mid-winter. The highest recorded temperature, 101 °F (38 °C), occurred on July 21, 1941, while the lowest observed temperature, 24 °F (−4 °C), occurred on December 29, 1894.[65] In some years, the dry season can become quite dry, and water restrictions are imposed.[66]

| Climate data for Palm Beach International Airport (West Palm Beach, Florida) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 89 (32) |

90 (32) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

99 (37) |

100 (38) |

101 (38) |

97 (36) |

97 (36) |

95 (35) |

92 (33) |

90 (32) |

101 (38) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 75 (24) |

77 (25) |

79 (26) |

82 (28) |

86 (30) |

88 (31) |

90 (32) |

90 (32) |

88 (31) |

85 (29) |

80 (27) |

76 (24) |

83 (28) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 57 (14) |

59 (15) |

62 (17) |

66 (19) |

71 (22) |

74 (23) |

76 (24) |

76 (24) |

75 (24) |

72 (22) |

66 (19) |

60 (16) |

68 (20) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 26 (−3) |

27 (−3) |

26 (−3) |

38 (3) |

45 (7) |

60 (16) |

64 (18) |

65 (18) |

61 (16) |

46 (8) |

36 (2) |

24 (−4) |

24 (−4) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.13 (80) |

2.82 (72) |

4.59 (117) |

3.66 (93) |

4.51 (115) |

8.30 (211) |

5.76 (146) |

7.95 (202) |

8.35 (212) |

5.13 (130) |

4.75 (121) |

3.38 (86) |

62.33 (1,585) |

| Source: National Weather Service[64][65] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1920 | 1,135 | — | |

| 1930 | 1,707 | 50.4% | |

| 1940 | 3,747 | 119.5% | |

| 1950 | 3,886 | 3.7% | |

| 1960 | 6,055 | 55.8% | |

| 1970 | 9,086 | 50.1% | |

| 1980 | 9,729 | 7.1% | |

| 1990 | 9,814 | 0.9% | |

| 2000 | 10,468 | 6.7% | |

| 2010 | 8,348 | −20.3% | |

| Est. 2019 | 8,816 | [7] | 5.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[67] | |||

Palm Beach ranks as the 16th largest municipality in Palm Beach County in terms of population, with 8,816 permanent residents according to 2019 estimates by the United States Census Bureau.[68] The town's peaked at 10,468 people in the 2000 census but fell by 20.3% to 8,348 people in 2010.[48] However, during the "winter season", defined as November through April, the population of Palm Beach swells to approximately 25,000.[69] The town's affluence and its recreational facilities, shops, restaurants, social scene, and "community-oriented sensibility" were cited when it was selected in June 2003 as America's "Best Place to Live" by Robb Report magazine.[70]

Between 2014 and 2018, the median household income in Palm Beach was $133,026, more than twice the county mean of $59,943 and the state average of $53,267. Per capita income over the same time period in Palm Beach was $178,568, far higher than the county average of $37,998 and the state average of $30,197.[71] Palm Beach ranked as the 27th-wealthiest place in the United States in 2016 according to Bloomberg News.[72] In the following year, Forbes reported that the town had 30-plus billionaires.[73] Palm Beach also has a considerably smaller percentage of minority populations in comparison to the county and state averages. Estimates in 2018 by the American Community Survey indicated that 92.9% of the town's population was non-Hispanic white, versus 54.1% for Palm Beach County and 53.5% for Florida.[71]

2010 census

As of the 2010 census, there were 8,348 people, 4,799 households, and 2,453 families residing in the town. The population density was 1,997.6 inhabitants per square mile (771.3/km2). There were 9,091 housing units at an average density of 2,164.5 inhabitants per square mile (835.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 97.4% White, 0.6% African American, less than 0.1% Native American, 1.0% Asian, less than 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.5% from other races, and 0.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.9% of the population.[74]

Over half the population of the town (55.8%) were 65 years of age or older, with a median age of 67.4 years. Approximately 6.9% were under the age of 18, 4.9% were from 18 to 24, 4.6% were from 25 to 44, and 27.8% from 45 to 64. For every 100 males, there were 123 females. For every 100 males age 18 and over, there were 125.8 females. Around 9.4% of the households in 2010 had children under the age of 18 living with them, 27.2% were married couples living together, 2.7% had a female householder with no spouse present, and 47.8% were non-families. About 48.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 65.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.74 and the average family size was 2.28.[74]

2000 census

As of the 2000 census, there were 10,468 people, 5,789 households, and 3,022 families residing in the town. The population density was 2,669.2 inhabitants per square mile (1,030.6/km2). There were 9,948 housing units at an average density of 2,368.6 per square mile (914.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 96% White, 2.6% African American, less than 0.1% Native American, 0.5% Asian, less than 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.2% from other races, and 0.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.6% of the population.[75]

Over half the population of the town (52.7%) were 65 years of age or older, with a median age of 67 years. About 9.4% were under the age of 18, 1.5% were from 18 to 24, 11.5% were from 25 to 44, and 25.0% from 45 to 64. For every 100 females, there were 79.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 77.0 males. Approximately 7.7% of the households in 2000 had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.1% were married couples living together, 3.3% had a female householder with no spouse present, and 47.8% were non-families. About 42.6% of all households were made up of individuals and 66.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.81 and the average family size was 2.38.[75]

English was the first language of 87.81% of all residents in 2000, while French comprised 4.48%, Spanish consisted of 3.65%, German made up 2.16%, Italian speakers made up 0.45%, Yiddish made up 0.36%, Russian was at 0.30%, Arabic and Swedish at 0.25%, and Polish was the mother tongue of 0.24% of the population.[76]

Palm Beach had the 40th highest percentage of Russian residents in the United States in 2010, with 10.30% of the populace – tied with Pomona, New York, and the township of Lower Merion, Pennsylvania.[77] It also had the 26th highest percentage of Austrian residents in the United States, at 2.10% of the town's population, tied with 19 other municipalities in the United States.[78]

In 2000, the household income for the town was $109,219. Males had a median income of $71,685 versus $42,875 for females. 5.3% of the population and 2.4% of families were below the poverty line. 4.6% of those under the age of 18 and 2.9% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line. Palm Beach had a median household income of $124,562 and a median family income of $137,867.[75]

Economy

In 2018, the town of Palm Beach had an estimated labor force of 2,788 people. Palm Beach has an unemployment rate of just 2.3%, although 66% of the town's population is not in the labor force. The most common professions among the town's labor force are finance, insurance, real estate, rental, and leasing (24.1%); professional, scientific, management, administrative, and waste management services (23.6%); retail (12.2%); and educational services, health care, and social assistance (10.5%).[79] However, as of 2017, only 4.1% of jobs in Palm Beach were held by residents of the town, with the most common other home destinations being West Palm Beach (15.4%), Palm Beach Gardens (3.9%), Lake Worth Beach (3.7%), Wellington (3.3%), and Greenacres (3.1%).[80]

Tourism is a major industry in the town, bringing in approximately $5 billion in annual revenue.[81] Palm Beach has several historical and luxurious hotels and lodgings, most notably The Brazilian Court, The Breakers,[82] the Palm Beach Hotel (now the Palm Beach Hotel Condominium),[83] the Tideline Ocean Resort & Spa, and the Vineta Hotel.[82] The Breakers alone employs more than 2,200 people from around the world.[84] The town of Palm Beach also contains Worth Avenue, an upscale shopping and dining district. Known for selling high-quality merchandise since the 1920s, Worth Avenue includes about 250 high-end shops, boutiques, restaurants, and art galleries.[85] Other commercial districts of note include Royal Poinciana Plaza and Royal Poinciana Way Historic District, with the latter being listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2015 due to its status as "the town's original Main Street", as noted by the Palm Beach Daily News.[86][87]

Arts and events

The Society of the Four Arts is a non-profit charity organization established in 1936. Located on the north side of Royal Palm Way near the Royal Park Bridge, the Four Arts Plaza contains an art gallery, a concert hall auditorium, two libraries, a botanical garden, and a sculpture garden. The two libraries serve as public libraries for the town of Palm Beach, one being a children's library and the other functioning as a general public library. Officially named the Gioconda and Joseph King Library, the town's general public library has a collection of more than 70,000 items, including books, audiobooks, DVDs, and periodicals. The Dixon Education Building features art studio and classrooms, as well as an apartment for an artist visiting the Society of the Four Arts.[88]

Royal Poinciana Playhouse, located near Cocoanut Row and Royal Poinciana Way, formerly hosted ballets, Broadway plays, opera, and other cultural events.[58]:VI-8 Although the venue has been closed since 2004, it remains structurally sound. Up Markets acquired control of the playhouse in 2014 via a long-term release. Negotiations and plans for reopening the playhouse are ongoing as of 2020.[89]

Worth Avenue and its vicinity also contains several art galleries, including DTR Modern Galleries, Evey Fine Art Gallery, Galeria of Sculpture, Gallerie Y, and the John H. Surovek Gallery. Additionally, the Norton Museum of Art and its sculpture gardens are located just across the Intracoastal Waterway in West Palm Beach.[90]

The Hope for Depression Research Foundation hosts an annual 5K run/walk known as the Race of Hope to Defeat Depression. In 2020, the event raised about $400,000 for depression research.[91] The Palm Beach International Film Festival had been hosted in the town in the months of March and April since 1996. However, the festival has been on hiatus since 2018, following the resignation of CEO Jeff Davis.[92] Various are hosted on Worth Avenue, including historical walking tours held year-round.[93] Once a year, the Palm Beach Charity Register magazine publishes a guide to charitable events held in the town and other nearby localities. A total of 186 charity galas, luncheons, and parties scheduled between the fall of 2019 and summer of 2020 were promoted by the magazine.[94]

Attractions

Whitehall reopened as the Flagler Museum on February 6, 1960, after Henry Flagler's granddaughter, Jean Flagler Matthews, purchased the property in 1959 to prevent its demolition.[18] Listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 and the National Historic Landmark list in 2000,[95] the museum replicates the original appearance of the house and has exhibits about Flagler himself,[96] Flagler's personal railcar (built in 1886),[18] the Florida East Coast Railway, life in the Gilded Age, and the early history of Palm Beach.[96] Almost 100,000 people visit the museum annually.[18] Adjacent to the Flagler Museum and behind the Royal Poinciana Chapel is a giant, 190-year old kapok tree, which also attracts visitors.[97]

The Preservation Foundation of Palm Beach established Pan's Garden in 1994 along Hibiscus Avenue between Chilean Avenue and Peruvian Avenue. The garden contains a statue of Pan (originally designed in 1890 by Frederick William MacMonnies), the Ancient Greek God who protects and guards flocks. Another significant feature is the Casa Apava wall, a 1920s tile wall from the remnants of the Casa Apava estate. Encompassing approximately 0.5 acres (0.20 ha), the garden also features many endangered species of native vegetation.[98]

Bethesda-by-the-Sea, originally a mostly wooden structure built from lumber from the beach in April 1889, is the oldest church in Palm Beach. The church opened at its current location by Christmas 1926.[99] Bethesda-by-the-Sea has hosted the weddings of a few notable individuals, including Donald and Melania Trump in 2005 and Michael Jordan and Yvette Prieto in 2013.[100]

Other points of interest

The Palm Beach Chamber of Commerce identifies several other points of interest in the town, including:[101]

- Major Alley - Located on Peruvian Avenue just one block north of the western terminus of Worth Avenue, Major Alley (named after architect Howard Major) contains six Georgian revival-style cottages built in the 1920s.[102]

- Royal Poinciana Chapel - Built in 1897 by Henry Flagler, he intended for the interdenominational chapel to be used by guests at his hotels. The chapel expanded to 400 seats about a year later. It is located adjacent to the Whitehall property.[103]

- Seagull Cottage - Situated between the Royal Poinciana Chapel and Whitehall, Seagull Cottage is the oldest surviving home in the Palm Beach, constructed in 1886 by R.R. McCormick, a railroad and land developer from Denver. Flagler purchased Seagull Cottage from McCormick in 1893 for $75,000, and it remained his winter residence until 1902, when Whitehall was completed.[104]

- Phipps Plaza Historic District - Described by the Palm Beach Daily News as a "picturesque ensemble" of buildings, the Phipps Plaza Historic District is a tight ring of structures built between the 1920s and the 1940s. Located just north of the intersection of Royal Palm Way and South County Road, the buildings at Phipps Plaza were mostly constructed by the Palm Beach Company, with the assistance of Addison Mizner and Marion Sims Wyeth.[105]

- The Colony Hotel Palm Beach - A British Colonial-style hotel located at South County Road and Hammond Avenue, just one block south of Worth Avenue. Opened in 1947, the six floor hotel contains eighty-nine rooms and three penthouses.[106]

- Addison Mizner Memorial Fountain - Erected by Mizner himself in 1929, the fountain is located in the middle of South County Road directly north of the town hall and to the west of the police department headquarters. The fountain is constructed of double-bowl cast stone. In 2017, the restoration of the fountain was named the project of the year by the American Public Works Association's Florida chapter.[51]

Parks and recreation

The Recreation Department of Palm Beach oversees several public recreation facilities, including the Morton and Barbara Mandel Recreation Center, Palm Beach Docks, Par 3 Golf Course, and many tennis centers.[107] The only public marina in the town, the Palm Beach Docks opened in the 1940s and is located along the Intracoastal Waterway between the Royal Palm Bridge and Worth Avenue.[108] Palm Beach Docks has three main docks and eighty-eight boat slips, along with many accommodations for boaters.[107]

There are three public beaches in the town, the Palm Beach Municipal Beach, Phipps Ocean Park, and R. G. Kreusler Park.[109] The former, also known as Midtown Beach,[110] has metered parking spots along South Ocean Boulevard from Royal Palm Way southward to Hammon Avenue.[111] Phipps Ocean Park includes the Little Red Schoolhouse, the first school building in southeast Florida (built in 1886), restored and moved from its original location near where the Flagler Memorial Bridge stands today.[112] The town also has many private beaches, while R. G. Kreusler Park (owned and operated by Palm Beach County) lies directly north of the Lake Worth Municipal Beach.[110] In addition to Pan's Garden, the Preservation Foundation of Palm Beach also owns the Ambassador Earl T. Smith Memorial Park and Fountain, a small, 0.24 acre (0.097 ha) park near the town hall.[58]:VI-8

The town has three bicycling and pedestrian paths. The Lake Trail is a 4.7 mile (7.6 km) path along the Intracoastal Waterway from Worth Avenue to near the Lake Worth Inlet. Another trail, the County Road Pedestrian Path/Bicycle Lane is around 1.1 miles (1.8 km) in length from Kawama Lane to Bahama Lane along North County Road. The third path is the Southern Pedestrian/Bicycle Path, running from Sloan's Curve to the town's southern boundaries along State Road A1A, a distance of roughly 3.5 miles (5.6 km).[58]:VI-7

Palm Beach has several social and golf clubs, most notably the Everglades Club and Mar-a-Lago. The former, constructed by Addison Mizner and Paris Singer in 1918, had the original purpose of being a hospital for soldiers injured in World War I. However, the war soon ended and the facilities were restructured into a private club, which opened in January 1919.[113] Some of the amenities include a golf course, tennis courts, and reception halls. Everglades Club has nearly 1,000 members. The club, which is very exclusive, does not have a website and prohibits cellphones.[114] Mar-a-Lago is 126-room, 62,500-square-foot (5,810 m2) mansion that features many hotel-style amenities.[44][45] Built between 1924 to 1927, General Foods and Post Cereals heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post originally owned the estate,[42] but willed it to the United States government prior to her death in 1973 in hopes that the residence would be used as a Winter White House.[43] Mar-a-Lago was returned to the Post family in 1981, before being sold to future United States president Donald Trump in 1985 for approximately $10 million.[44]

Government

Palm Beach operates under a council–manager form of government. The town's legislative body, the town council, is composed of five members, who serve two-year terms and seek office in staggered, at-large, non-partisan elections. Once a month, the town council meets at the Palm Beach Town Hall, though special meetings may be conducted as needed. The mayor, also elected to two year terms, acts as ombudsman and an intergovernmental figure.[115] Gail L. Coniglio, a former two-term member of the town council, has served as mayor since 2011.[116] Additionally, a town manager has the authority to appoint and supervise the senior management team, including the deputy town manager and department directors. The officeholder of town manager is appointed annually by the town council.[115] Kirk Blouin, a former Palm Beach chief of police and later Director of Public Safety, has served as town manager since February 13, 2018.[116]

Palm Beach is part of Florida's 21st congressional district, which has been represented by Democrat Lois Frankel since 2017.[117] The town at the state level is part of the 89th district of the Florida House of Representatives, which covers many of the immediate coastal cities in Palm Beach County from Palm Beach Shores southward.[118] Palm Beach is also part of the 30th district of the Florida Senate, which includes northeastern and some of east-central Palm Beach County.[119] Two districts represent the town at the Palm Beach County Board of County Commissioners. The town north of Worth Avenue is part of the 1st district,[120] while the 7th district covers areas south of Worth Avenue.[121] Palm Beach is a generally Republican town. In 2016, Donald Trump received 3,231 votes and Hillary Clinton received 2,612 votes.[122]

Education

The School District of Palm Beach County operates one school in the town, Palm Beach Public Elementary School, located on Cocoanut Row between Seaview Avenue and Royal Palm Beach and directly east of the Society of the Four Arts. Opened in 1929, Palm Beach Public Elementary School has a school grade of A and an attendance of 362.[123] Palm Beach Day Academy is a private school in the area. It was formed in 2006 from a merger between Palm Beach Day School and the Academy of the Palm Beaches. The school has one campus in Palm Beach and another in West Palm Beach.[124] Most public middle school students attend Conniston Community Middle School in West Palm Beach, while students residing in the southern portions of the town attend Lake Worth Middle School.[125] Public high school students in northern Palm Beach attend Palm Beach Gardens Community High School and students residing elsewhere in the town attend Forest Hill Community High School. Palm Beach is also located near Dreyfoos School of the Arts, though that school has no attendance boundaries.[126]

There are no colleges or universities in the town of Palm Beach. However, the nearby cities of Lake Worth Beach and West Palm Beach contain a few public and private higher education institutes, including Keiser University, Palm Beach Atlantic University, and Palm Beach State College.[127]

Media

The town is served by the Palm Beach Daily News, with a daily circulation of approximately 4,500.[128] The Palm Beach Daily News began publishing in 1897 under the name Daily Lake Worth News.[129] Between 1925 and 1974, the newspapers was published in a building that has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1985. Owned by Cox Enterprises since 1969, GateHouse Media purchased the newspaper and The Palm Beach Post in May 2018.[128] The Palm Beach Daily News is also known as "The Shiny Sheet" due to its former heavy, slick newsprint stock.[129]

Residents of the town are also served by The Palm Beach Post, which is actually published in West Palm Beach.[130] The Palm Beach Post had the 5th largest circulation for a newspaper in Florida as of November 2017 and is served to subscribers throughout Palm Beach County and the Treasure Coast.[130][131]

Palm Beach is part of the West Palm Beach–Fort Pierce television market, ranked as the 38th largest in the United States by Nielsen Media Research.[132] The market is served by stations affiliated with major American networks including WPTV-TV/5 (NBC), WPEC/12 (CBS), WPBF/25 (ABC), WFLX/29 (FOX), WTVX/34 (CW), WXEL-TV/42 (PBS), WTCN-CD/43 (MYTV),[133] WWHB-CD/48 (Azteca),[134] WHDT/59 (Court TV),[133] WFGC/61 (CTN),[134] WPXP-TV/67 (ION),[133] as well as local channel WBWP-LD/57 (Ind.).[134] Since 2017, the Palm Beach Civic Association has produced weekly video newscasts, known as Palm Beach TV, which have a weekly viewership of approximately 12,000.[135]

Many radio stations are located within range of the town. Radio stations WRMF (97.9 FM) and WPBV-LP (98.3 FM) are both based in the town of Palm Beach.[136]

Historic preservation

The Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC), established by an ordinance approved by the town council in 1979, studies and protects historic structures in Palm Beach. Currently, the LPC has a list of 328 properties, sites, and vistas it works to protect under the 1979 ordinance.[41] Similarly, the Preservation Foundation of Palm Beach is "dedicated to preserving the architectural and cultural heritage and the unique scenic quality of the Town of Palm Beach", according to its mission statement.[137] The town of Palm Beach also conducts historic sites surveys in collaboration with preservation organizations, historians, and local officials, with the most recent survey completed in 2010, though a new survey began in November 2019.[138] The 2010 survey identified 50 structures that had been demolished since the previous survey in 2004 and others that had been altered significantly.[139]:52

Federally, thirteen structures and one historic district have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[87][139]:24 However, two of the designated buildings have since been destroyed.[139]:24 A fire and subsequent burglaries at the Bingham-Blossom House likely contributed to the owner's decision to have it demolished in 1974,[140] while construction crews razed the Brelsford House in 1975 after trustees at the Royal Poinciana Chapel (the property where the building was located at) believed that "the aging structure was more of a liability than an asset" and also cited its high costs of renovation for public use, according to The Palm Beach Post.[141]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Three bridges traverse the Intracoastal Waterway, linking Palm Beach and West Palm Beach by roadway.[142] The northernmost bridge, the Flagler Memorial Bridge, is located along State Road A1A,[142] which is locally known as Royal Poinciana Way in Palm Beach and Quadrille Boulevard in West Palm Beach.[143] First opening in 1938,[19] the bridge underwent a 5-year reconstruction and renovation between 2012 and 2017 at a cost of $106 million.[144] State Road 704, also known as Royal Palm Way in Palm Beach and Lakeview Avenue and Okeechobee Boulevard in West Palm Beach is the location of the middle bridge.[143] Named the Royal Park Bridge, it first opened in 1911 and was most recently replaced in 2005.[19] The Southern Boulevard Bridge at the conjunction of U.S. Route 98 and State Road 80 (locally known as Southern Boulevard) is the southernmost bridge.[145] First completed in 1950, the bridge is currently undergoing a $93 million replacement project, scheduled for completion in the summer of 2021.[146]

State Road A1A also runs northward through much of Palm Beach, beginning at the southern limits of the town as South Ocean Boulevard until being redirected onto South County Road, which later becomes North County Road. At Royal Poinciana Way, A1A turns westward onto that road and across the Flagler Memorial Bridge.[147] State Roads 80 and 704 and U.S. Route 98 all terminate shortly after entering the town after intersecting with A1A.[143][145] The town has no interstate highways,[143][145] though Interstate 95 passes through the nearby city of West Palm Beach.[148] Private vehicles and taxis are the predominant means of transport in Palm Beach. Incidents of profiling of lower-cost cars and minorities have occurred, sometimes resulting in tense relations between visitors and the town.[149]

The nearby city of West Palm Beach has two train stations. Tri-Rail and Amtrak serve the Tamarind Avenue station,[150] while the higher speed Virgin Trains USA serves the Evernia Street station.[151] Palm Beach is located about 4.5 miles (7.2 km) east of the Palm Beach International Airport.[152] The northern and central portions of Palm Beach are served by Palm Tran Route 41, which travels to places in the town such as the Lake Worth Inlet, North County Road and Wells Road, Publix (Bradley Place and Sunrise Avenue), Royal Palm Way (State Road 704) and South County Road (State Road A1A), and various points between. The route returns to the Intermodal Transit Center in West Palm Beach, which connects to several other bus routes and is adjacent to the train station on Tamarind Avenue.[153]

Police

The town has its own police department, established on October 17, 1922. Prior to then, town marshal Joseph Borman served in the capacity of chief law enforcer as outlined in the 1911 charter.[154] The department employed 61 officers in 2018. With a population of 8,295 people in 2018 according to the Florida Bureau of Economic and Business Research, this translated to 7.35 officers per 1,000 people, compared to the Florida average of 2.49 officers per 1,000 people. In the same year, the department made 2,039 arrests – equal to about 24,581 arrests per 100,000 people, the highest arrest rate in Florida and over sevenfold the state average. However, many arrests were in relation to non-violent crimes, such as those involving auto theft, criminal traffic citations, fraud, and scams. The police department reported no rapes or homicides in Palm Beach in 2018.[155]

Firefighting

In its early days, the town of Palm Beach depended heavily on the city of West Palm Beach for firefighting efforts. The Flagler Alerts, a volunteer firefighting group which later became the West Palm Beach Fire Department, responded to fires in Palm Beach by traversing the Intracoastal Waterway via ferry or railroad. Delayed response times and high insurance rates eventually led Palm Beach to establish its own fire rescue department in December 1921.[156] Today, the Palm Beach Fire Rescue has three stations, retains 82 employees – 75 full-time and 7 part-time, and annually responds to approximately 2,600 calls.[157]

Utilities

Florida Power & Light (FPL) provides electricity to the town of Palm Beach, along with much of the state's east coast. As of December 31, 2019, FPL serves 5 million customers statewide, which is approximately 10 million people.[158]:5 Much of the electricity supplied by FPL is sourced from natural gas, followed by nuclear energy.[158]:8 The nearest FPL power plant is located in Riviera Beach,[159] while the closest nuclear power station is the St. Lucie Nuclear Power Plant, situated on Hutchinson Island.[158]:8 Palm Beach officials have considered undergrounding at least since commissioning a 2006 study on the burial of electrical lines. In the subsequent years, undergrounding projects were initially performed by neighborhood on a "as requested" basis. However, following a 2014 town council meeting with FPL workers and a related voter-approved ballot question in 2016, it was decided that a town-wide undergrounding project would be undertaken at a cost of approximately $90 million.[160] The project is ongoing as of March 2020.[161]

The town government provides and oversees sewage systems and wastewater treatment. Sewage is collected via 41 miles (66 km) of mainline pipes at the more than 40 pumping stations, which are capable of transporting over 100,000 US gallons (380,000 l; 83,000 imp gal) of water each minute. The sewage is then pumped into a regional wastewater treatment facility in West Palm Beach.[162] Tap water has been supplied by the city of West Palm Beach since 1955, when the city purchased Palm Beach's water system, then owned by the Flagler Water Company. West Palm Beach provided tap water services to the town at no cost until the beginning of 1995.[163]

Recycling and garbage collection services are also provided by the town of Palm Beach. The former is taken to a transfer station, where the Palm Beach County Solid Waste Authority transports the garbage to a landfill in West Palm Beach.[58]:IV-3–IV-4 Vegetative yard trash is taken to two different sites in West Palm Beach.[58]:IV-5

Notable people

The town of Palm Beach is also known for its many famous part-time and full-time residents. Prior to the arrival of Henry Flagler in the 1890s, a few wealthy or otherwise notable people already resided in Palm Beach, including businessman and Autocar Company founder Louis Semple Clarke and scientist Thomas Adams, a pioneer of the chewing gum industry.[23][15] Earl E. T. Smith and Paul Ilyinsky, both of whom formerly held the office of Mayor of Palm Beach, were notable for other reasons. Smith previously served as an Ambassador of the United States to Cuba, while Ilyinsky was the son of Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia and heiress Audrey Emery.[17]

Two United States Presidents have been part-time residents, John F. Kennedy and Donald Trump, with both designating their respective Palm Beach properties as a Winter White House.[17][45] Kennedy's Winter White House, La Querida, was built by Addison Mizner in 1923 and previously owned by department store magnate Rodman Wanamaker of Philadelphia before Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. purchased the property in 1933.[164] Trump has owned Mar-a-Lago since 1985, purchasing the property from the family of the late Marjorie Merriweather Post, heiress of Post cereal.[44] In October 2019, Trump and first lady Melania Trump filed to switch their primary domicile from New York City to Mar-a-Lago, officially establishing residency in Palm Beach.[165] Additionally, former Canadian prime minister Brian Mulroney has been a resident of Palm Beach at least since 2003.[166]

References

- "1860 - 1879". Historical Society of Palm County. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- "Story of the Town's Founding". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- "From The Archives: Shipwreck, its coconuts led to Palm Beach's name". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- "Viva Florida 500: History happened here - Palm Beach History". vivafl500.org. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- "Mayor & Town Council". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Palm Beach". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. October 19, 1979. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- "Cocoanut Grove House". Waymarking.com. August 8, 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "1880 - 1889". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "Reaching Out: Mail Routes". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "Henry M. Flagler in Florida Timeline". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "The Grand Hotels: The Royal Poinciana". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "1890 - 1899". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "Flagler Era". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "The Grand Hotels: The Breakers". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "Timeline". Palm Beach Daily News. February 9, 1997. p. B6. Retrieved April 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Whitehall". Flagler Museum. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "Key Historical Dates & Events". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Dr. Sherry Piland; Emily Stillings; Ednasha Bowers (2005). Historic Preservation: A Design Guidelines Handbook (PDF) (Report). Historic Preservation Board, City of West Palm Beach. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- "Henry Flagler, his town, and the fire". The St. Augustine Record. McClatchy. February 6, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- "Palm Beach". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Eliot Kleinberg (February 7, 2001). "Cap Dimick, Palm Beach's first mayor, a pioneer but no captain". The Palm Beach Post. p. 14R. Retrieved April 17, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Caroline Seebohm (2001). Boca Rococo. How Addison Mizner Invented Florida's Gold Coast. Clarkson Potter. p. 170. ISBN 978-0609605158.

- "Architects: Mizner in Palm Beach". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- Donald W. Curl (1992). Mizner's Florida. The Architectural History Foundation and the MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262530682.

First published 1984

- "8 Great Addison Mizner Buildings". Old House Journal. October 26, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- "Worth Avenue". The Cultural Landscape Foundation. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (PDF) (Report). National Park Service. 2005. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- "Palm Beach Hurricane—92 Views". Chicago, Illinois: American Autochrome Company. 1928. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- Julie Waresh (May 30, 1999). "Profiting from failure". The Palm Beach Post. p. 1F. Retrieved April 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Timeline". Palm Beach Daily News. February 9, 1997. p. B7. Retrieved June 5, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "This week in history: Flagler Memorial Bridge opens". The Palm Beach Post. June 8, 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- "Flagler Bridge Dedication Program Will Open Formally Memorial Span To Traffic". The Palm Beach Post. July 1, 1938. p. 1. Retrieved May 13, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "U.S. Military in Palm Beach". Historical Society of Palm Beach. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- "Local Response: Blackout Restrictions". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- "The Enemy Presence: German U-Boats". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Joe Capozzi (August 7, 2018). "Flagler Bridge: Sunday's breakdown caused by loose bolt". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- William Kelly (December 17, 2018). "Palm Beach history: Early preservationist's passion shines throughout exhibit". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- "Historic Preservation". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Don Sider (June 18, 1995). "Party Time at Mar-a-Lago". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Kerry Gruson (July 16, 1981). "Post Home For Sale For $20". The New York Times. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Terry Spencer (September 8, 2017). "For Irma vs. Mar-a-Lago, the smart money is on Trump's house". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Robert Frank (January 25, 2017). "Mar-a-Lago membership fee doubles to $200,000". CNBC. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- Dennis McLellan (October 7, 2002). "Mollie Wilmot; Palm Beach Socialite Played Host to Cargo Ship in 1984". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- Kirk Brown (November 1, 1991). "20-footers pummel shoreline, damage homes, sea walls, pier". The Palm Beach Post. p. 1A. Retrieved May 13, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- David Rogers (May 7, 2011). "Palm Beach tracking down reasons Census shows population drop for town". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- "Jeffrey Epstein: How the case unfolded in Palm Beach County". Palm Beach Daily News. November 13, 2019. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- Margie Kacoha (April 18, 2011). "Promenade kicks off celebration with costumes, music, fancy cars". Palm Beach Daily News. p. 1. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- William Kelly (March 14, 2017). "Palm Beach's Mizner Fountain named 'project of the year'". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- Harvey Oyer III (November 4, 2001). "The Wreck of the Providencia in 1878 and the Naming of Palm Beach County". South Florida History. 29.

- Dermot O'Brien (June 1, 2014). "Question: Why do you like Singer Island?". The Palm Beach Post. p. R10. Retrieved April 27, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Federal Writers' Project (1939). Florida. A Guide to the Southernmost State. Oxford University Press. p. 227.

- "Town History Past and Present". Town of Palm Beach Shores. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "Municipalities of Palm Beach County, Florida" (PDF). Palm Beach County Planning, Zoning and Building Department. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- Town of Palm Beach Comprehensive Plan (PDF) (Report). Town of Palm Beach Planning, Zoning, and Building Department. March 30, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "Palm Beach County orders mandatory evacuations for Zones A and B". WPEC. September 1, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "Evacuation and Re-Entry". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- "West Palm Beach, Florida". Weatherbase. Retrieved May 4, 2014.

- "Duration of Summer Season in South Florida". National Weather Service Miami, Florida. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- Nicole Sterghos Brochu (September 14, 2003). "Florida's forgotten storm: The Hurricane of 1928". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- "West Palm Beach" (PDF). National Weather Service Miami, Florida. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- "Climatological Records for West Palm Beach, FL Highlights 1888–2019 Daily Extremes" (PDF). National Weather Service Miami, Florida. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- Kimberly Miller (April 10, 2020). "Driest March triggers conservation order: Limits on watering landscapes". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Palm Beach - County in Florida". citypopulation.de. May 23, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "Town of Palm Beach, Florida, Comprehensive Annual Budget Fiscal Year 2018" (PDF). Town of Palm Beach. p. 34. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- Shelia Gibson Stoodley (July 1, 2003). "Robb Report's Best Places to Live". Robb Report. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "QuickFacts - Palm Beach town, Florida; Palm Beach County, Florida; Florida". United State Census Bureau. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- Shelly Hagan; Wei Lu (March 5, 2018). "Bloomberg - America's 100 Richest Places". Bloomberg News. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Darrell Hofheinz (March 21, 2017). "Forbes' billionaires list has 30-plus Palm Beachers; Trump's worth drops". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- "Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2010" (PDF). Florida Office of Economic & Demographic Research. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000" (PDF). Treasure Coast Regional Planning Council. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "MLA Data Center Results of Palm Beach, FL". Modern Language Association. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "Ancestry Map of Russian Communities". Epodunk.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "Ancestry Map of Austrian Communities". Epodunk.com. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- "Selected Economic Characteristics". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "Home Destination Analysis". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Lizandra Portal; Luli Ortiz (March 16, 2020). "Town-wide curfew issued in Palm Beach as city declares state of emergency". WPEC. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "Hotels". Palm Beach Chamber Of Commerce. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "About Us". Palm Beach Hotel Condominium. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- "Workplace Information". The Breakers Palm Beach. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- David Segal (April 11, 2009). "Recession Pain, Even in Palm Beach". The New York Times. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Aleese Kopf (August 31, 2017). "Check out 12 new luxury shops coming to Palm Beach's Royal Poinciana Plaza this fall". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- David Rogers (September 24, 2016). "Royal Poinciana Way added to National Register of Historic Places". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- "About The Society of the Four Arts". The Society of the Four Arts. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Jan Sjostrom (January 15, 2020). "Council members grow impatient with search for playhouse tenant". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "Directory". Worth Avenue. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Gabrielle Mayer (February 15, 2020). "Race of Hope raises $400K for depression research". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- Phillip Valys (January 19, 2018). "Palm Beach International Film Festival calls off 2018 event". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "Events". Worth Avenue. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- Liz Petoniak (October 2019). "Good Neighbors". Palm Beach Charity Register. p. 8. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- Aleese Kopf (September 4, 2016). "Thousands take in Founder's Day at Flagler Museum". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- "Past Exhibitions". Flagler Museum. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- "Historic kapok 'a magnificent piece of living art'". Palm Beach Daily News. September 26, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- "Pan's Garden". Preservation Foundation of Palm Beach. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- Michele Dargan (June 22, 2014). "Celebrating 125 years: 'Faithful people' built Bethesda-by-the-Sea". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- Staci Sturrock (June 25, 2015). "Which 5 celebrities got married in Palm Beach (and Jupiter)?". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "Points of Interest". A Visitor's Map of Palm Beach. Palm Beach Chamber of Commerce. p. 4. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- Pilar Viladas (November 17, 2015). "A Look Inside Some of the Most Whimsical Homes in Palm Beach". Town & Country. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- Rev. Robert Norris (February 27, 2017). "Royal Poinciana Chapel reflects on 120 years in Palm Beach". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "Buildings & Grounds". Royal Poinciana Chapel. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- Augustus Mayhew (March 22, 2017). "Architects gave Phipps Plaza distinctive look". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "Checking In: Colony Hotel in Palm Beach has historic pedigree". Sun-Sentinel. February 16, 2010. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "Recreation Department". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- "Town Docks". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- "Palm Beach – Beaches & Watersports". Discover The Palm Beaches. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- William Kelly (November 28, 2017). "Beach access in Palm Beach remains a source of confusion". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- "Palm Beach Public Beach". City of West Palm Beach. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- "Teaching and Preaching". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- "Private Clubs". Historical Society of Palm Beach County. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Barbara Marshall (April 17, 2011). "An exclusive look inside the mysterious Everglades Club". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- "Town Officials". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- "Gail L. Coniglio, Mayor". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- "Florida's 21st Congressional District". GovTrack. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "H000H9049 (2012 House), District 89" (PDF). Florida House of Representatives Redistricting Committee. 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "Florida State Senate District 30" (PDF). Florida Senate. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "Palm Beach County District 1" (PDF). GIS Service Bureau. December 6, 2016. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "Palm Beach County District 7" (PDF). GIS Service Bureau. December 6, 2016. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- Matthew Bloch; Larry Buchanan; Josh Katz; Kevin Quealy (July 25, 2018). "An Extremely Detailed Map of the 2016 Presidential Election". The New York Times. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- "School Information". School District of Palm Beach County. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "Thompson retirement may mean move to Maryland". Palm Beach Daily News. June 7, 2007. p. A12. Retrieved May 9, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Middle School Attendance Boundaries SY2019–20" (PDF). School District of Palm Beach County. 2019. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "High School Attendance Boundaries SY2019–20" (PDF). School District of Palm Beach County. 2019. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "Colleges & Universities". Business Development Board of Palm Beach County. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "Palm Beach Post to be sold to GateHouse in $49M deal". Sun-Sentinel. Associated Press. March 28, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Eliot Kleinberg (February 2, 2017). "'Shiny Sheet' celebrates 120 years". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- "Company Profile". Business Development Board of Palm Beach County. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- "Daily Times Circulation" (PDF). Tampa Bay Times. November 2017. p. 2. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- "Nielsen DMA–Designated Market Area Regions 2018-2019" (PDF). Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- "Local DIRECTV Packages and Channels in West Palm Beach". DIRECTV. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- "Stations for West Palm Beach, Florida". RabbitEars. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- "This Week in Palm Beach Newscasts". Palm Beach Civic Association. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- "City search (Palm Beach, Florida)". radio-locator.com. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- "Mission". Preservation Foundation of Palm Beach. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Adriana Delgado (November 7, 2019). "Palm Beach's historic site survey gets under way". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Town of Palm Beach, Florida 2010 Historic Sites Survey (PDF) (Report). Research Atlantica, Inc. December 2010. p. 52. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Joyce Heard (August 15, 1974). "Bingham-Blossom House To Be Torn Down in Fall". The Palm Beach Post. p. C3. Retrieved April 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Historic Crash". The Palm Beach Post. August 22, 1975. p. C1. Retrieved April 24, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Drawbridge openings in Palm Beach County" (PDF). Palm Beach County Board of County Commissioners. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- "Roadway Atlas (Page 60)" (PDF). Palm Beach County Engineering and Public Works. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- Thomas Forester (July 31, 2017). "Flagler Memorial Bridge reopens". WPEC. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- "Roadway Atlas (Page 72)" (PDF). Palm Beach County Engineering and Public Works. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- "SR 80 (Southern Blvd) Bridge Replacement Project". Florida Department of Transportation. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- "Straight-Line Diagrams Online GIS Web Application - Roadway: 93060000 SR A1A". Florida Department of Transportation. pp. 11–15. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- "Roadway Atlas (Page 59)" (PDF). Palm Beach County Engineering and Public Works. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- Kevin Noble Maillard (July 23, 2013). "Racially Profiled in Palm Beach". The Atlantic. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- "PBI Public Transportation". Palm Beach International Airport. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- "West Palm Beach". Brightline. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- "How close is the nearest airport?". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- "West Palm Beach to Palm Beach Inlet - Route 41" (PDF). Palm Beach County Government. 2020. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- "History of the Police Department". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- Wendy Rhodes (August 19, 2019). "Palm Beach Police Dept. has the highest arrest rate in Florida, but what does that actually mean?". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- "Expanded History". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- "About the Department". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- NextEra Energy Annual Report 2019 (PDF) (Report). NextEra Energy. December 31, 2019.

- "Riviera Beach Next Generation Clean Energy Center". Florida Power & Light Company. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- "Underground Utilities". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- "Undergrounding Program - Status Update As of March 30, 2020". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- "Water Resources". Town of Palm Beach. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- Tim O'Meilia (August 13, 1997). "Town set to pursue suit over water fee". The Palm Beach Post. p. 1B. Retrieved April 26, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Darrell Hofheinz (May 29, 2015). "UPDATED: Former Kennedy estate in Palm Beach sells for $31M". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Eliot Kleinberg (October 31, 2019). "Trump leaving New York, making Mar-a-Lago his permanent residency". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- Shannon Donnelly (March 4, 2003). "American Ireland Fund fetes Mulroney". Palm Beach Daily News. Retrieved May 12, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Palm Beach, Florida. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Palm Beach, Florida. |