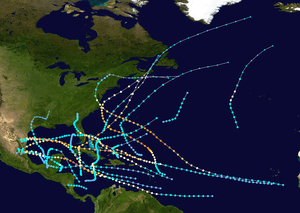

1933 Treasure Coast hurricane

The 1933 Treasure Coast hurricane was the second-most intense tropical cyclone to strike the United States during the active 1933 Atlantic hurricane season. The eleventh tropical storm, fifth hurricane, and the third major hurricane of the season, it formed east-northeast of the Leeward Islands on August 31. The tropical storm moved rapidly west-northwestward, steadily intensifying to a hurricane. It acquired peak winds of 140 miles per hour (225 km/h) and passed over portions of the Bahamas on September 3, including Eleuthera and Harbour Island, causing severe damage to crops, buildings, and infrastructure. Winds over 100 mph (161 km/h) affected many islands in its path, especially those that encountered its center, and many wharves were ruined.

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Surface weather analysis of the hurricane on September 3 near the Bahamas | |

| Formed | August 31, 1933 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 7, 1933 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 140 mph (220 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | ≤ 945 mbar (hPa); 27.91 inHg |

| Fatalities | 3 total |

| Damage | $3 million (1933 USD) |

| Areas affected | The Bahamas, Florida, Georgia, The Carolinas |

| Part of the 1933 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Subsequently, it weakened and made landfall at Jupiter, Florida, early on September 4 with winds of 125 mph (201 km/h). The hurricane moved across the state, passing near Tampa before moving into Georgia and dissipating. In Florida, the strong winds of the cyclone blew buildings off their foundations, and numerous trees were prostrated in citrus groves. The Treasure Coast region received the most extensive destruction, and Stuart, Jupiter, and Fort Pierce were heavily damaged. Inland, the cyclone weakened rapidly but produced prodigious amounts of rain, causing a dam to collapse near Tampa. The storm caused $3 million in damage (1933 USD) after damaging or destroying 6,848 homes.

Unusually, the storm hit Florida less than 24 hours before another major hurricane bearing 125-mile-per-hour (201 km/h) winds struck South Texas; never have two major cyclones hit the United States in such close succession.[1]

Meteorological history

The origins of the hurricane were from a tropical wave that possibly spawned a tropical depression on August 27, although there was minimal data over the next few days as it tracked to the west-northwest. On August 31, a nearby ship reported gale-force winds, which indicated that a tropical storm had developed to the east-northeast of the Lesser Antilles. Based on continuity, it is estimated the storm attained hurricane status later that day. Moving quickly to the west-northwest, the storm passed north of the Lesser Antilles and Puerto Rico. Early on September 2, a ship called the Gulfwing reported a barometric pressure of 978 mbar (28.88 inHg), which confirmed that the storm attained hurricane status.[2] After passing north of the Turks and Caicos islands,[3] the hurricane struck Eleuthera and Harbour Island in the Bahamas on September 3, the latter at 1100 UTC. A station on the latter island reported a pressure of 27.90 inHg (945 mb) during the 30 minute passage of the eye.[4] Based on the pressure and the small size of the storm, it is estimated the hurricane struck Harbour Island with peak winds of 140 mph (225 km/h), making it the equivalent of a modern Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale. Interpolation suggested that the storm reached major hurricane status, or Category 3 status, on September 2.[2]

The hurricane initially followed the course of another hurricane that passed through the area in late August, which ultimately struck Cuba and Texas. This hurricane instead maintained a general west-northwest track.[3][5] After moving through the northern Bahamas, the hurricane weakened slightly before making landfall at Jupiter, Florida, at 0500 UTC on September 4. A station there reported a pressure of 27.98 inHg (948 mb) during a 40-minute period of the eye's passage; this suggested a landfall strength of 125 mph (201 km/h). At the time, the radius of maximum winds was 15 mi (24 km), which was smaller than average. After landfall, the hurricane weakened rapidly while crossing the state. It briefly emerged into the Gulf of Mexico as a tropical storm early on September 5. A few hours later while continuing to the northwest, it made another landfall near Rosewood—a ghost town in Levy County, east of Cedar Key—with winds of about 65 mph (105 km/h). Turning to the north, the storm slowly weakened as it crossed into Georgia, dissipating on September 7 near Augusta.[2]

Preparations and impact

On September 2, a fleet of eight aircraft evacuated all white residents from West End, Grand Bahama, to Daytona Beach, Florida.[6] While the storm was near peak intensity on September 3, the Weather Bureau issued hurricane warnings from Miami to Melbourne, Florida, with storm warnings extending northward to Jacksonville. Later that day, storm warnings, were issued from Key West to Cedar Key.[3] About 2,500 people evacuated by train from areas around Lake Okeechobee.[7] By evening on September 3, high tides sent sea spray over coastal seawalls in Palm Beach County as residents boarded up buildings; structures on Clematis Street in West Palm Beach were said to be a "solid front" of plywood.[8] Along the coast, observers reported very rough seas as the eye neared land.[9]

The powerful hurricane moved over or near several islands in the Bahamas. Winds on Spanish Wells and Harbour Island were both estimated at around 140 mph (225 km/h).[2][4] Winds reached 110 mph (177 km/h) at Governor's Harbour, 100 mph (161 km/h) on Eleuthera, and 120 mph (193 km/h) on the Abaco Islands.[4][10][11] The storm was farther away from Nassau, where winds reached 61 mph (98 km/h).[2][10] The hurricane damaged a lumber mill on Abaco, washing away a dock. Heavy damage occurred on Harbour Island, including to several roofs, the walls of government buildings, and the water system. The hurricane destroyed four churches and 37 houses, leaving 100 people homeless. A 1.5 mi (2.4 km) road on Eleuthera was destroyed. Several islands sustained damage to farms, including the total loss of various fruit trees on Russell Island. Despite Category 4 winds on Spanish Wells, only five houses were destroyed, although most of the remaining dwellings lost their roofs. Collectively between North Point, James Cistern, and Gregory Town on Eleuthera, the storm destroyed 55 houses and damaged many others. On Grand Bahama, where a 9 to 12 ft (2.7 to 3.7 m) storm surge was reported, half of the houses were destroyed, as were 13 boats and two planes, and most docks were wrecked.[4]

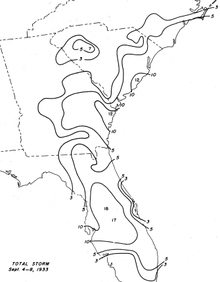

When the storm moved ashore in Florida, winds reached an estimated 125 mph (201 km/h) in Jupiter; these occurred after the eye passed.[3][12] In West Palm Beach, anemometers measured at least 80-mile-per-hour (129 km/h) winds with gusts to 100 mph (161 km/h); barometers ranged from 28.64 to 28.78 inHg (970 to 975 mb).[13] The storm produced the strongest winds in the city since the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane.[14] Winds were not as strong farther from the center; 40 to 45 mph (64 to 72 km/h) winds were observed in Miami to the south, Titusville to the north, and Tampa on the west coast.[2] Fort Pierce estimated peak winds of 80 to 90 mph (129 to 145 km/h), and pressures dipped to 29.14 inHg (987 mb).[15] Inland, winds near Lake Okeechobee peaked at only 60 mph (97 km/h).[16] The hurricane dropped heavy rainfall along its path, peaking at 17.8 in (450 mm) in Clermont.[5]

At West Palm Beach, the majority of the damage was confined to vegetation. Several coconut and royal palms that withstood the 1928 hurricane snapped, littering streets with broken trunks.[14] Winds downed road signs on many streets, and floodwaters covered the greens on a local golf course.[17] Some garages and isolated structures, mostly lightweight, were partly or totally destroyed, along with a lumber warehouse. Some homes that lost roofing shingles had water damage to their interiors as well.[14] Nearby Lake Worth sustained extensive breakage of windows, including plate glass, and loss of tile and shingle roofing, but preparations reduced losses to just several thousand dollars, and no post-storm accidents took place. Strong winds snapped many light poles in the city, and trees and shrubs were broken or uprooted.[18] As in Lake Worth, officials in West Palm Beach credited preparations and stringent building codes with reducing overall damage. The city had learned from previous experience with severe storms in 1926, 1928, and 1929.[14] High tides eroded Ocean Boulevard at several spots and disrupted access to several bridges on the Lake Worth Lagoon. Winter estates and hotels on Palm Beach generally sustained little material damage, except to vegetation, and county properties went largely unscathed.[14]

In Martin and St. Lucie counties, the storm was considered among the worst on record.[12] The storm leveled some homes and swept many others off their foundations.[19] At Stuart, winds removed or badly damaged 75% of the roofs in town. The storm destroyed the third floor of the building that housed a bowling alley and the Stuart News, a local newspaper.[12][17] At Olympia, an abandoned settlement also known as Olympia Beach, strong winds leveled the old Olympia Inn, a gas station, and the second floor of a pharmaceutical building. Winds also tore the roof off an ice plant.[17][20] A bridge leading to the barrier island from Olympia was partly wrecked; the bridge tender survived by gripping the railing during the storm. Winds leveled his nearby home.[20] According to the Monthly Weather Review, some of the most severe damage from the storm in Florida was at Olympia.[3] The storm left many homes in Hobe Sound uninhabitable, forcing crews to tear them down. Winter estates on the island, however, were better built and little damaged. While Stuart and Hobe Sound sustained significant damage, Port Salerno suffered minimally.[20] In Stuart, the storm left 400 to 500 people homeless, up to nearly 10% of the population, which was 5,100 at the time.[12][21] Between Jupiter and Fort Pierce, the storm knocked down power and telegraph lines.[3] In the latter city, high waves washed out a portion of the causeway.[22] In the 1980s, an elderly resident recalled that the storm was the most severe on record in Fort Pierce.[19]

Crop damage was worst along the Indian River Lagoon; several farms in Stuart experienced total losses, and statewide, 16% of the citrus crop, or 4 million boxes, were destroyed.[3] Many chicken coops in Stuart were destroyed, and the local chicken population was scattered and dispersed as far as Indiantown.[12] Across southeastern Florida, the hurricane damaged 6,465 houses and destroyed another 383,[23] causing over $3 million in damage.[24] One person, an African American farm worker, was killed when his shack blew down in Gomez,[20] a brakeman died after seven railcars derailed,[25] and a child was killed by airborne debris.[12]

High rainfall caused flooding across Florida, notably near Tampa where waters reached 9 ft (2.7 m) deep. High rainfall of over 7 in (180 mm) caused a dam operated by Tampa Electric Co. to break 3 mi (4.8 km) northeast of Tampa along the Hillsborough River. The break resulted in severe local damage,[12][25] flooding portions of Sulphur Springs. Workers attempted to save the dam with sandbags, and after the break, most residents in the area were warned of the approaching flood. Over 50 homes were flooded, forcing about 150 people to evacuate.[26] Outside Florida, the storm produced winds of 48 and 51 mph (77 and 82 km/h) in Savannah, Georgia and Charleston, South Carolina, respectively. In the latter city, the storm spawned a tornado,[2] which caused about $10,000 in property damage.[25] Heavy rainfall occurred along the Georgia and South Carolina coasts, reaching over 12 in (300 mm). Light rainfall also extended into North Carolina.[5]

Aftermath

In the Bahamas after the storm, a boat sailed from Nassau to deliver food and building materials to Eleuthera.[4]

After the storm, the National Guard offered shelters for at least 400 homeless residents in Stuart.[12] Of the 7,900 families adversely affected by the hurricane, 4,325 required assistance from the American Red Cross.[23] Farmers in Texas, also affected by a major hurricane, requested growers in Florida wait 15 days so they could sell their citrus crop that fell.[27] The damaged dam near Tampa initially resulted in waters from the Hillsborough River being pumped into the city's water treatment plant, and a new dam was eventually built in 1944.[28]

See also

- Hurricane Frances

- List of Florida hurricanes (1900–49)

Notes

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- Chris Landsea; et al. (May 2012). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT (1933) (Report). Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 2013-09-19.

- C. L. Mitchell (October 1933). "Tropical Disturbances of September 1933" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 61 (9): 275–276. Bibcode:1933MWRv...61..274M. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1933)61<274:TDOS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2013-09-19.

- Neely 2006, pp. 84–8

- R.W. Schoner, R.W.; S. Molansky; Sinclair Weeks; F.W. Reichelderfer; W.M. Brucker; S.D. Sturgis (July 1956). Rainfall Associated With Hurricanes (And Other Tropical Disturbances) (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: National Hurricane Research Project. p. 160. Retrieved 2013-09-20.

- "Pilots Leave Island in Face of Storm". Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach. September 4, 1933.

- "Throngs Flee as Hurricane Perils Florida". The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. 1933-09-04. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Residents Ready for Storm Winds as Boards Go Up". Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach. September 4, 1933.

- "Northwest Wind at Lauderdale". Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach. Associated Press. September 4, 1933.

- "Nassau Reports Strong Winds". Palm Beach Post. Associated Press. September 4, 1933.

- "City Near Storm Center". Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach. Associated Press. September 4, 1933.

- Barnes 1998, pp. 141–3

- "Winds Were Felt over Large Area on East Coast". Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach. September 5, 1933.

- "Storm's Damage Checked in City as Blow Passes". Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach. September 5, 1933.

- "Fort Pierce Area Has Heavy Damage". Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach. September 5, 1933.

- "Rain and Not Wind Damages Farm Area". Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach. September 6, 1933.

- "Storm Sidelights". Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach. September 5, 1933.

- "Lake Worth Checks on Storm Damage". Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach. September 5, 1933.

- Duedall & Williams 2002, p. 19

- "East Coast Hard Hit by Hurricane Winds; Storm Across State". Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach. September 5, 1933.

- "Stuart Homeless Numerous; Help Is Sought Here". Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach. Associated Press. September 6, 1933.

- "Gales Sweep Over Florida". The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. 1933-09-05. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Checkup on Losses in Hurricane Show Total to Be Larger". The Palm Beach Post. 1933-09-09. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Red Cross Workers Bring Aid to Storm Sufferers in Some Florida Sections". The Evening Post. Associated Press. 1933-09-07. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- Mary O. Souder (September 1933). "Severe Local Storms" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 61 (9): 291. Bibcode:1933MWRv...61..291.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1933)61<291:slss>2.0.co;2. Retrieved 2013-09-19.

- "Sulphur Springs Flooded as Huge Dam Bursts Open". The Evening Independent. 1933-09-08. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- "Texas Appeals to Florida to Hold Up Fruit". The Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Associated Press. 1933-09-08. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

- History of the City of Tampa Water Department (PDF) (Report). Tampa, Florida Water Department. 2012-04-11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-25. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

Bibliography

- Barnes, Jay (1998), Florida's Hurricane History, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 0-8078-4748-8

- Duedall, Iver W.; Williams, John M. (2002), Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms, 1871–2001, University Press of Florida, ISBN 978-0-8130-2494-3

- Neely, Wayne (2006), The Major Hurricanes to Affect the Bahamas: Personal Recollections of Some of the Greatest Storms to Affect the Bahamas, Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse, ISBN 1-4259-6608-X