Key West

Key West (Spanish: Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it constitutes the City of Key West.

Key West from space, October 2002 | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 24°33′55″N 81°46′33″W[1] |

| Archipelago | Florida Keys |

| Area | 4.2 sq mi (11 km2) |

| Length | 4 mi (6 km) |

| Width | 1 mi (2 km) |

| Highest elevation | 18 ft (5.5 m) |

| Highest point | Solares Hill, 18 ft (5.5 m) above sea level |

City of Key West, Florida | |

|---|---|

Aerial photo of Key West, looking north, April 2001 | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): "The Conch Republic", "Southernmost City in the Continental United States" | |

| Motto(s): One Human Family | |

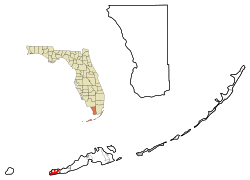

Location in Monroe County and the state of Florida | |

U.S. Census Bureau map showing city limits | |

Key West Location of Key West in Florida  Key West Key West (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 24°33′55″N 81°46′33″W[1] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Monroe |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Mayor | Teri Johnston |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7.21 sq mi (18.67 km2) |

| • Land | 5.59 sq mi (14.48 km2) |

| • Water | 1.62 sq mi (4.19 km2) |

| Elevation | 18 ft (5 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 24,649 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 24,118 |

| • Density | 4,314.49/sq mi (1,665.81/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 33040, 33041, 33045 |

| Area code(s) | 305 and 786 (305 Exchanges: 292,293,294,295,296,320,809) |

| FIPS code | 12-36550[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0294048[5] |

| Website | Official website |

The Island of Key West is about 4 miles (6 kilometers) long and 1 mile (2 km) wide, with a total land area of 4.2 square miles (11 km2).[6] It lies at the southernmost end of U.S. Route 1, the longest north–south road in the United States. Key West is about 95 miles (153 km) north of Cuba at their closest points.[7][8] It is also 130 miles (210 km) southwest of Miami by air, about 165 miles (266 km) by road,[9] and 106 miles (171 km) north-northeast of Havana.[7]

The City of Key West is the county seat of Monroe County, which includes all of the Florida Keys and part of the Everglades.[10] The total land area of the city is 5.6 square miles (14.5 km2).[11] The official city motto is "One Human Family".

Key West is the southernmost city in the contiguous United States and the westernmost island connected by highway in the Florida Keys. Duval Street, its main street, is 1.1 miles (1.8 km) in length in its 14-block-long crossing from the Gulf of Mexico to the Straits of Florida and the Atlantic Ocean. Key West is the southern terminus of U.S. Route 1, State Road A1A, the East Coast Greenway and, before 1935, the Florida East Coast Railway. Key West is a port of call for many passenger cruise ships.[12] The Key West International Airport provides airline service. Naval Air Station Key West is an important year-round training site for naval aviation due to the tropical weather, which is also the reason Key West was chosen as the site of President Harry S. Truman's Winter White House. The central business district is located along Duval Street and includes much of the northwestern corner of the island.

History

Precolonial and colonial times

At various times before the 19th century, people who were related or subject to the Calusa and the Tequesta inhabited Key West. The last Native American residents of Key West were Calusa refugees who were taken to Cuba when Florida was transferred from Spain to Great Britain in 1763.[13]

Cayo Hueso (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈkaʝo ˈweso]) is the original Spanish name for the island of Key West. Spanish-speaking people today also use the term when referring to Key West. It literally means "bone cay", cay referring to a low island or reef. It is said that the island was littered with the remains (bones) of prior native inhabitants, who used the isle as a communal graveyard.[14] This island was the westernmost Key with a reliable supply of water.[15]

Between 1763, when Great Britain took control of Florida from Spain, and 1821, when the United States took possession of Florida from Spain, there were few or no permanent inhabitants anywhere in the Florida Keys. Cubans and Bahamians regularly visited the Keys, the Cubans primarily to fish, while the Bahamians fished, caught turtles, cut hardwood timber, and salvaged wrecks. Smugglers and privateers also used the Keys for concealment. In 1766 the British governor of East Florida recommended that a post be set up on Key West to improve control of the area, but nothing came of it. During both the British and Spanish periods no nation exercised de facto control. The Bahamians apparently set up camps in the Keys that were occupied for months at a time, and there were rumors of permanent settlements in the Keys by 1806 or 1807, but the locations are not known. Fishermen from New England started visiting the Keys after the end of the War of 1812, and may have briefly settled on Key Vaca in 1818.[16]

Ownership claims

In 1815, the Spanish governor of Cuba in Havana deeded the island of Key West to Juan Pablo Salas, an officer of the Royal Spanish Navy Artillery posted in Saint Augustine, Florida. After Florida was transferred to the United States in 1821, Salas was so eager to sell the island that he sold it twice – first for a sloop valued at $575 to a General John Geddes, a former governor of South Carolina, and then to a U.S. businessman John W. Simonton, during a meeting in a Havana café on January 19, 1822, for the equivalent of $2,000 in pesos in 1821. Geddes tried in vain to secure his rights to the property before Simonton who, with the aid of some influential friends in Washington, was able to gain clear title to the island. Simonton had wide-ranging business interests in Mobile, Alabama. He bought the island because a friend, John Whitehead, had drawn his attention to the opportunities presented by the island's strategic location. John Whitehead had been stranded in Key West after a shipwreck in 1819 and he had been impressed by the potential offered by the deep harbor of the island. The island was indeed considered the "Gibraltar of the West" because of its strategic location on the 90-mile (140 km)–wide deep shipping lane, the Straits of Florida, between the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico.

On March 25, 1822, Lt. Commander Matthew C. Perry sailed the schooner USS Shark to Key West and planted the U.S. flag, claiming the Keys as United States property.[17] No protests were made over the American claim on Key West, so the Florida Keys became the property of the United States.

After claiming the Florida Keys for the United States, Perry renamed Cayo Hueso (Key West) to Thompson's Island for Secretary of the Navy Smith Thompson, and the harbor Port Rodgers in honor of War of 1812 hero and President of the Navy Supervisors Board John Rodgers. In 1823, Commodore David Porter of the United States Navy West Indies Anti-Pirate Squadron took charge of Key West, which he ruled (but, according to some, exceeding his authority) as military dictator under martial law. The United States Navy gave Porter the mission of countering piracy and the slave trade in the Key West area.

First developers

Soon after his purchase, John Simonton subdivided the island into plots and sold three undivided quarters of each plot to:

- John Mountain and U.S. Consul John Warner, who quickly resold their quarter to Pardon C. Greene, who took up residence on the island. Greene is the only one of the four "founding fathers" to establish himself permanently on the island, where he became quite prominent as head of P.C. Greene and Company. He was a member of the city council[18] and also served briefly as mayor. He died in 1838 at the age of 57.

- John Whitehead, his friend who had advised him to buy Key West.[19] John Whitehead lived in Key West for only eight years. He became a partner in the firm of P.C. Greene and Company from 1824 to 1827. A lifelong bachelor, he left the island for good in 1832. He came back only once, during the Civil War in 1861, and died the next year.

- John Fleeming (nowadays spelled Fleming).[19] John W.C. Fleeming was English-born and was active in mercantile business in Mobile, Alabama, where he befriended John Simonton. Fleeming spent only a few months in Key West in 1822 and left for Massachusetts, where he married. He returned to Key West in 1832 with the intention of developing salt manufacturing on the island but died the same year at the age of 51.

Simonton spent the winter in Key West and the summer in Washington, where he lobbied hard for the development of the island and to establish a naval base on the island, both to take advantage of the island's strategic location and to bring law and order to the town. He died in 1854.

The names of the four "founding fathers"[20] of modern Key West were given to main arteries of the island when it was first platted in 1829 by William Adee Whitehead, John Whitehead's younger brother. That first plat and the names used remained mostly intact and are still in use today. Duval Street, the island's main street, is named after Florida's first territorial governor, who served between 1822 and 1834 as the longest-serving governor in Florida's U.S. history.

William Whitehead became chief editorial writer for the "Enquirer", a local newspaper, in 1834. He preserved copies of his newspaper as well as copies from the "Key West Gazette", its predecessor. He later sent those copies to the Monroe County clerk for preservation, which gives us a view of life in Key West in the early days (1820–1840).

In the 1830s, Key West was the richest city per capita in the United States.[21]

In 1852 the first Catholic Church, St. Mary's Star-Of-The-Sea was built. The year 1864 became a landmark for the church in South Florida when five Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary arrived from Montreal, Canada, and established the first Catholic school in South Florida. At the time it was called Convent of Mary Immaculate. The school is still operating today and is now known as Mary Immaculate Star of the Sea School.

American Civil War and late 19th century

During the American Civil War, while Florida seceded and joined the Confederate States of America, Key West remained in U.S. Union hands because of the naval base. Most locals were sympathetic to the Confederacy, however, and many flew Confederate flags over their homes.[22] Fort Zachary Taylor, constructed from 1845 to 1866, was an important Key West outpost during the Civil War. Construction began in 1861 on two other forts, East and West Martello Towers, which served as side armories and batteries for the larger fort. When completed, they were connected to Fort Taylor by railroad tracks for movement of munitions.[22] Fort Jefferson, located about 68 miles (109 km) from Key West on Garden Key in the Dry Tortugas, served after the Civil War as the prison for Dr. Samuel A. Mudd, convicted of conspiracy for setting the broken leg of John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of President Abraham Lincoln.

In the 19th century, major industries included wrecking, fishing, turtling, and salt manufacturing.[23] From 1830 to 1861, Key West was a major center of U.S. salt production, harvesting the commodity from the sea (via receding tidal pools) rather than from salt mines.[23] After the outbreak of the Civil War, Union troops shut down the salt industry after Confederate sympathizers smuggled the product into the South.[23] Salt production resumed at the end of the war, but the industry was destroyed by an 1876 hurricane and never recovered, in part because of new salt mines on the mainland.[23]

During the Ten Years' War (an unsuccessful Cuban war for independence in the 1860s and 1870s), many Cubans sought refuge in Key West.

A fire on April 1, 1886 that started at a coffee shop next to the San Carlos Institute and spread out of control, destroyed 18 cigar factories and 614 houses and government warehouses.[24]

By 1889, Key West was the largest and wealthiest city in Florida.[22]

The USS Maine sailed from Key West on her fateful visit to Havana, where she blew up and sank in Havana Harbor, igniting the Spanish–American War. Crewmen from the ship are buried in Key West, and the Navy investigation into the blast occurred at the Key West Customs House.

20th century

Key West was relatively isolated until 1912, when it was connected to the Florida mainland via the Overseas Railway extension of Henry M. Flagler's Florida East Coast Railway (FEC). Flagler created a landfill at Trumbo Point for his railyards. The Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 destroyed much of the railroad and killed hundreds of residents, including around 400 World War I veterans who were living in camps and working on federal road and mosquito-control projects in the Middle Keys. The FEC could not afford to restore the railroad.

The U.S. government then rebuilt the rail route as an automobile highway, completed in 1938, built atop many of the footings of the railroad. It became an extension of U.S. Route 1. The portion of U.S. 1 through the Keys is called the Overseas Highway. Franklin Roosevelt toured the road in 1939.

Pan American Airlines was founded in Key West, originally to fly visitors to Havana, in 1926. The airline contracted with the United States Postal Service in 1927 to deliver mail to and from Cuba and the United States. The mail route was known as the Key West, Florida – Havana Mail Route.

John F. Kennedy was to use "90 miles from Cuba" extensively in his speeches against Fidel Castro. Kennedy himself visited Key West a month after the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Prior to the Cuban revolution of 1959, there were regular ferry and airplane services between Key West and Havana.

In 1982, the city of Key West briefly asserted independence as the Conch Republic as a protest over a United States Border Patrol blockade. This blockade was set up on US 1, where the northern end of the Overseas Highway meets the mainland at Florida City, in response to the Mariel Boatlift. A traffic jam of 17 miles (27 km) ensued while the Border Patrol stopped every car leaving the Keys, supposedly searching for illegal immigrants attempting to enter the mainland United States. This paralyzed the Florida Keys, which rely heavily on the tourism industry. Flags, T-shirts and other merchandise representing the Conch Republic are still popular souvenirs for visitors to Key West, and the Conch Republic Independence Celebration– including parades and parties –is celebrated annually, on April 23.

In 2017, Hurricane Irma caused substantial damage with wind and flooding, killing three people.

Geography

Key West is an island located at 24°33′55″N 81°46′33″W[1] in the Straits of Florida. The island is about 4 miles (6 km) long and 1 mile (2 km) wide, with a total land area of 4.2 square miles (10.9 km2; 2,688.0 acres).[6] The average elevation above sea level is about 8 feet (2.4 m) and the maximum elevation is about 18 feet (5.5 m), within a 1-acre (0-hectare) area known as Solares Hill.[25][26]

The city of Key West is the southernmost city in the contiguous United States,[6] and the island is the westernmost island connected by highway in the Florida Keys. The city boundaries include the island of Key West and several nearby islands, as well as the section of Stock Island north of U.S. Route 1, on the adjacent key to the east. The total land area of the city is 5.6 square miles (15 km2).[11] Sigsbee Park—originally known as Dredgers Key—and Fleming Key, both located to the north, and Sunset Key located to the west are all included in the city boundaries. Both Fleming Key and Sigsbee Park are part of Naval Air Station Key West and are inaccessible to the general public.

In the late 1950s, many of the large salt ponds on the eastern side of the island were filled in. The new section on the eastern side is called New Town, which contains shopping centers, retail malls, residential areas, schools, ball parks, and Key West International Airport.

Key West and most of the rest of the Florida Keys are on the dividing line between the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. The two bodies have different currents, with the calmer and warmer Gulf of Mexico being characterized by great clumps of seagrass. The area where the two bodies merge between Key West and Cuba is called the Straits of Florida. The warmest ocean waters anywhere on the United States mainland are found in the Florida Keys in winter, with sea surface temperatures averaging in the 75–77 °F (24–25 °C) range in December through February.

Duval Street, its main street, is 1.1 miles (1.8 km) in length in its 14-block-long crossing from the Gulf of Mexico to the Straits of Florida and the Atlantic Ocean.

Key West is closer to Havana (about 106 miles or 171 kilometres by air or sea)[7] than it is to Miami (130 miles or 210 kilometres by air or 165 miles or 266 kilometres by road).[9] Key West is the usual endpoint for marathon swims from Cuba, including Diana Nyad's 2013 record-setting swim as the first completed without a shark cage or fins[27][28] and Susie Maroney's 1997 swim from within a shark cage.[29]

Notable places

Old Town

.jpg)

The earliest Key West neighborhoods, on the western part of the island, are broadly known as Old Town. The Key West Historic District includes the major tourist destinations of the island, including Mallory Square, Duval Street, the Truman Annex and Fort Zachary Taylor. Old Town is where the classic bungalows and guest mansions are found. Bahama Village, southwest of Whitehead Street, features houses, churches, and sites related to its Afro-Bahamian history. The Meadows, lying northeast of the White Street Gallery District, is exclusively residential.

Generally, the structures date from 1886 to 1912. The basic features that distinguish the local architecture include wood-frame construction of one- to two-and-a-half-story structures set on foundation piers about three feet (one meter) above the ground. Exterior characteristics of the buildings are peaked metal roofs, horizontal wood siding, gingerbread trim, pastel shades of paint, side-hinged louvered shutters, covered porches (or balconies, galleries, or verandas) along the fronts of the structures, and wood lattice screens covering the area elevated by the piers.

Some antebellum structures survive, including the Oldest (or Cussans-Watlington) House (1829–1836)[30] and the John Huling Geiger House (1846–1849), now preserved as the Audubon House and Tropical Gardens.[31] Fortifications such as Fort Zachary Taylor,[32] the East Martello Tower,[33] and the West Martello Tower,[34] helped ensure that Key West would remain in Union control throughout the Civil War. Another landmark built by the federal government is the Key West Lighthouse, now a museum.[35]

Two of the most notable buildings in Old Town, occupied by prominent twentieth-century residents, are the Ernest Hemingway House, where the writer lived from 1931 to 1939, and the Harry S. Truman Little White House, where the president spent 175 days of his time in office.[36] Additionally, the residences of some historical Key West families are recognized on the National Register of Historic Places as important landmarks of history and culture, including the Porter House on Caroline Street[37] and the Gato House on Virginia Street.[38]

Several historical residences of the Curry family remain extant, including the Benjamin Curry House, built by the brother of Florida's first millionaire, William Curry,[39] as well as the Southernmost House and the Fogarty Mansion, built by the children of William Curry—his daughter Florida and son Charles, respectively.[40]

In addition to architecture, Old Town includes the Key West Cemetery, founded in 1847,[41] containing above-ground tombs, notable epitaphs, and a plot where some of the dead from the 1898 explosion of the USS Maine are buried.[42][43]

Casa Marina

The Casa Marina area takes its name from the Casa Marina Hotel, opened in 1921,[44] the neighborhood's most conspicuous landmark. The Reynolds Street Pier, Higgs Beach,[45] the West Martello Tower, the White Street Pier, and Rest Beach line the waterfront.

Southernmost point in the United States

One of the most popular attractions on the island is a concrete replica of a buoy at the corner of South and Whitehead Streets that claims to be the southernmost point in the contiguous United States. The point was originally marked with a basic sign. The city of Key West erected the current monument in 1983.[46] The monument was repainted after damage by Hurricane Irma in 2017, and is the most often photographed tourist site in the Florida Keys.[47]

The monument is labeled "Southernmost point continental U.S.A.", though Whitehead Spit is the actual southernmost point of Key West, on the Truman Annex property just west of the buoy. The spit has no marker since it is on U.S. Navy land that cannot be entered by civilian tourists. The private property directly to the east of the buoy, and the beach areas of Truman Annex and Fort Zachary Taylor Historic State Park, also lie farther south than the buoy. The southernmost point of the contiguous United States is Ballast Key, a privately owned island just south and west of Key West. The southernmost location that the public can visit is the beach at Fort Zachary Taylor park.

The monument states "90 Miles to Cuba", though Key West and Cuba are about 95 statute miles (153 kilometers; 83 nautical miles), apart at their closest points.[7][8] The distance from the monument to Havana is about 90 nautical miles (104 statute miles; 167 kilometers).[7]

Key West Library

The first public library was officially established in 1853, which was housed in the then-Masonic Temple on Simonston Street, near where the federal courthouse is today. At the time, the first library president was James Lock, with the librarian being William Delaney. At the time, the library collected held 1,200 volumes for residents to access.

In 1919, a hurricane destroyed the library. Key West residents moved the library to various locations across the island. The county took over and finally found a permanent location. The library's new location was found in 1959. It was built on Fleming Street, where it is still found today. At this time, there was also a book mobile service, which served the entire Keys.

The Key West Library has an ever expanding collection of 70,000 items. One of these includes a letter from singer/songwriter Jimmy Buffet. Dated from October 22, 1984, the letter expresses gratitude for the library in giving inspiration for the songs he would eventually write, and for the air conditioning.[48]

Notable residences

Little White House

Several U.S. presidents have visited Key West with the first being Ulysses S. Grant in 1880, followed by Grover Cleveland in 1889, and William Howard Taft in 1912.[49] Taft was the first president to use the first officer's quarters that would later be known as the Little White House.[50] Franklin D. Roosevelt visited the Florida Keys many times, beginning in 1917.[49]

Harry S. Truman visited Key West for a total of 175 days on 11 visits during his presidency and visited five times after he left office. His first visit was in 1946.[51] The Little White House and Truman Annex take their names from his frequent and well-documented visits. The residence is also known as the Winter White House as Truman stayed there mostly in the winter months, and used it for official business such as the Truman Doctrine.[52]

Dwight D. Eisenhower stayed at the Little White House following a heart attack in 1955.[49] John F. Kennedy visited Key West in March 1961, and in November 1962, a month after the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Jimmy Carter visited the Little White House twice with his family after he had left office, in 1996 and 2007.[51]

Ernest Hemingway house

Legend has it that Ernest Hemingway wrote part of A Farewell to Arms while living above the showroom of a Key West Ford dealership at 314 Simonton Street[53] while awaiting delivery of a Ford Model A roadster purchased by the uncle of his wife Pauline in 1928.[54]

Hardware store owner Charles Thompson introduced him to deep-sea fishing. Among the group who went fishing was Joe Russell (also known as Sloppy Joe). Russell was reportedly the model for Freddy in To Have and Have Not.[55] Portions of the original manuscript were found at Sloppy Joe's Bar after his death. The group had nicknames for each other, and Hemingway wound up with "Papa".

Pauline's rich uncle Gus Pfeiffer bought the 907 Whitehead Street house[56] in 1931 as a wedding present. The Hemingways installed a swimming pool for $20,000 in 1937–38 (equivalent to about $286 thousand in 2018). The unexpectedly high cost prompted Hemingway to put a penny in the wet cement of the patio, saying, "Here, take the last penny I've got!" The penny is at the north end of the pool.[57]

During his stay he wrote or worked on Death in the Afternoon, For Whom the Bell Tolls, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, and The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber. He used Depression-era Key West as one of the locations in To Have and Have Not—his only novel with scenes that occur in the United States.

The six- or seven-toed polydactyl cats descended from Hemingway's original pet "Snowball" still live on the grounds and are cared for at the Hemingway House, despite complaints by the U.S. Department of Agriculture that they are not kept free from visitor contact. The Key West City Commission has exempted the house from a law prohibiting more than four domestic animals per household.

Pauline and Hemingway divorced in 1939; Hemingway only occasionally visited when returning from Havana until his suicide in 1961.

Tennessee Williams house

Tennessee Williams first became a regular visitor to Key West in 1941 and is said to have written the first draft of A Streetcar Named Desire while staying in 1947 at the La Concha Hotel. He bought a permanent house in 1949 and listed Key West as his primary residence until his death in 1983. In contrast to Hemingway's grand house in Old Town, the Williams home at 1431 Duncan Street[58] in the "unfashionable" New Town neighborhood is a very modest bungalow. The house is privately owned and not open to the public. The Academy Award-winning film version of his play The Rose Tattoo was shot on the island in 1956. The Tennessee Williams Theatre is located on the campus of Florida Keys Community College on Stock Island.[59]

Even though Hemingway and Williams lived in Key West at the same time, they reportedly met only once—at Hemingway's home in Cuba, Finca Vigía.[60]

Port of Key West

The first cruise ship was the Sunward in 1969, which docked at the Navy's pier in the Truman Annex or the privately owned Pier B. The Navy's pier is called the Navy Mole.

In 1984, the city opened a pier right on Mallory Square. The decision was met with considerable opposition from people who felt it would disrupt the tradition of watching the sunset at Mallory Square. Cruise ships now dock at all three piers.

Cruise Ship Statistics for 1994:[61]

- Number of visits: 368

- Passenger count: 398,370

- City revenues from docking charges: $852,887

In present times, several cruise ships dock on a regular basis at Key West, including the Royal Caribbean ship Majesty of the Seas and the Carnival Fascination, both of which visit weekly. In the last several years, however, larger cruise ships have increasingly bypassed Key West due to the narrowness of the island's main ship channel. On October 1, 2013, 74% of resident voters opposed a referendum that would have allowed the City Commission to request a feasibility study from the Army Corps of Engineers for a $36 million project to dredge a wider channel.[62] Economic benefits from visiting cruise ship passengers are substantial but not attractive to all Key West citizens as the daily presence of thousands of tourists from cruise ships affects the character of the city, resulting in operation of facilities that cater to mass tourism rather than to an upscale clientele. There are also environmental issues as Key West is surrounded by coral habitat.[12] Concerns over environmental protection were considered a prominent factor in the failure of the 2013 referendum.[63]

As of 2009, there were 859,409 passengers annually.[64]

Climate

Key West has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw, similar to the Caribbean islands).[65] Like most tropical climates, Key West has only a small difference in monthly mean temperatures between the coolest month (January) and the warmest month (July) – with the annual range of monthly mean temperatures around 15 °F (8.3 °C). According to the National Weather Service, the Florida Keys and Miami Beach are the only places within the contiguous United States to have never recorded a frost or freeze. The lowest recorded temperature in Key West is 41 °F (5 °C) on January 12, 1886, and January 13, 1981. Key West is located in USDA zone 11b (the warmest zone in the contiguous United States). According to the National Weather Service in Key West, low temperatures below 50 F (10 C) occur on average four times per decade.

Prevailing easterly tradewinds and sea breezes suppress the usual summertime heating, with temperatures rarely reaching 95 °F (35 °C). There are 55 days per year with 90 °F (32 °C) or greater highs,[66] with the average window for such readings June 10 through September 22, shorter than almost the entire southeastern U.S. Low temperatures often remain above 80 °F (27 °C), however. The all-time record high temperature is 97 °F (36 °C) on July 19, 1880, and August 29, 1956.[66]

Wet and dry seasons

Like most tropical climates, Key West has a two-season wet and dry climate. The period from November through April is normally sunny and quite dry, with only 25 percent of the annual rainfall occurring. May through October is normally the wet season. During the wet season some rain falls on most days, often as brief, but heavy tropical downpours, followed by intense sun. Early morning is the favored time for these showers, which is different from mainland Florida, where showers and thunderstorms usually occur in the afternoon. Easterly (tropical) waves during this season occasionally bring excessive rainfall, while infrequent hurricanes may be accompanied by unusually heavy amounts. On average, rainfall markedly peaks between August and October; the single wettest month in Key West is September, when the threat from tropical weather systems (hurricanes, tropical storms and tropical depressions) is greatest. Key West is the driest city in Florida, averaging just under 40 inches of rain per year. This is driven primarily by Key West's relative dryness in May, June and July. In mainland Florida peninsular areas like Orlando, Tampa/St. Petersburg and Fort Myers, June and July average monthly rainfalls typically reach 7 to 10 inches, while Key West has only half such amounts over the same period.[67]

Hurricanes

Key West, like the rest of the Florida Keys, is vulnerable to hurricanes. In recent history, the island has been relatively unaffected by major storms. The most recent hurricane to impact Key West was Hurricane Irma, which made landfall in the Keys in the morning of September 10, 2017 as a Category 4 storm.

Some locals maintain that Hurricane Wilma on October 24, 2005, was the worst storm in memory. The entire island was told to evacuate and business owners were forced to shut their doors. After the hurricane had passed, the resulting storm surge sent eight feet (two meters) of water inland completely inundating a large portion of the lower Keys. Low-lying areas of Key West and the lower Keys, including major tourist destinations, were under as much as three feet (one meter) of water. Sixty percent of the homes in Key West were flooded.[68] The higher parts of Old Town, such as the Solares Hill and cemetery areas, did not flood, because of their higher elevations of 12 to 18 feet (4 to 5 m).[69] The surge destroyed tens of thousands of cars throughout the lower Keys, and many houses were flooded with one to two feet (thirty to sixty-one centimeters) of sea water. A local newspaper referred to Key West and the lower Keys as a "car graveyard".[70] The peak of the storm surge occurred when the eye of Wilma had already passed over the Naples area, and the sustained winds during the surge were less than 40 mph (64 km/h).[69] The storm destroyed the piers at the clothing-optional Atlantic Shores Motel and breached the shark tank at the Key West Aquarium, freeing its sharks. Damage postponed the island's famous Halloween Fantasy Fest until the following December. MTV's The Real World: Key West was filming during the hurricane and deals with the storm.

In September 2005, NOAA opened its National Weather Forecasting building on White Street. The building is designed to withstand a Category 5 hurricane and its storm surge.

The most intense previous hurricane was Hurricane Georges, a Category 2, in September 1998. The storm damaged many of the houseboats along "Houseboat Row" on South Roosevelt Boulevard near Cow Key channel on the east side of the island.

| Climate data for Key West Int'l, Florida (1981–2010 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1872−present)[lower-alpha 2] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 90 (32) |

87 (31) |

89 (32) |

91 (33) |

93 (34) |

96 (36) |

97 (36) |

97 (36) |

95 (35) |

93 (34) |

91 (33) |

88 (31) |

97 (36) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 82.0 (27.8) |

82.7 (28.2) |

84.2 (29.0) |

86.0 (30.0) |

88.6 (31.4) |

91.0 (32.8) |

92.0 (33.3) |

92.1 (33.4) |

91.1 (32.8) |

88.7 (31.5) |

85.6 (29.8) |

82.7 (28.2) |

92.6 (33.7) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 74.3 (23.5) |

76.0 (24.4) |

78.2 (25.7) |

81.3 (27.4) |

85.0 (29.4) |

87.8 (31.0) |

89.3 (31.8) |

89.4 (31.9) |

87.9 (31.1) |

84.5 (29.2) |

79.9 (26.6) |

76.0 (24.4) |

82.5 (28.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 69.3 (20.7) |

71.0 (21.7) |

73.2 (22.9) |

76.4 (24.7) |

80.3 (26.8) |

83.3 (28.5) |

84.5 (29.2) |

84.5 (29.2) |

83.2 (28.4) |

80.2 (26.8) |

75.8 (24.3) |

71.4 (21.9) |

77.8 (25.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 64.2 (17.9) |

66.0 (18.9) |

68.3 (20.2) |

71.6 (22.0) |

75.7 (24.3) |

78.8 (26.0) |

79.8 (26.6) |

79.6 (26.4) |

78.5 (25.8) |

76.0 (24.4) |

71.7 (22.1) |

66.9 (19.4) |

73.1 (22.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 51.0 (10.6) |

53.7 (12.1) |

57.4 (14.1) |

61.9 (16.6) |

69.5 (20.8) |

73.4 (23.0) |

74.1 (23.4) |

73.8 (23.2) |

73.6 (23.1) |

69.1 (20.6) |

62.2 (16.8) |

54.5 (12.5) |

48.8 (9.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 41 (5) |

44 (7) |

47 (8) |

48 (9) |

63 (17) |

65 (18) |

68 (20) |

68 (20) |

64 (18) |

59 (15) |

49 (9) |

44 (7) |

41 (5) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 2.04 (52) |

1.49 (38) |

2.05 (52) |

2.05 (52) |

3.00 (76) |

4.11 (104) |

3.55 (90) |

5.38 (137) |

6.71 (170) |

4.93 (125) |

2.30 (58) |

2.22 (56) |

39.83 (1,012) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.2 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 4.5 | 7.2 | 11.0 | 11.7 | 14.2 | 16.2 | 11.3 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 106.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76.0 | 74.3 | 73.0 | 70.1 | 71.8 | 74.0 | 72.2 | 73.4 | 75.3 | 75.1 | 76.0 | 76.2 | 74.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 249.6 | 245.4 | 308.8 | 324.6 | 340.3 | 314.0 | 325.2 | 306.6 | 269.6 | 254.7 | 230.9 | 234.5 | 3,404.2 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 75 | 77 | 83 | 85 | 82 | 77 | 78 | 76 | 73 | 71 | 70 | 71 | 77 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961−1990)[66][71][72], The Weather Channel[73] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Key West | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 71.2 (21.8) |

71.2 (21.8) |

73.2 (22.9) |

77.7 (25.4) |

80.6 (27.0) |

83.3 (28.5) |

85.5 (29.7) |

86.9 (30.5) |

85.5 (29.7) |

82.8 (28.2) |

78.4 (25.8) |

74.5 (23.6) |

79.2 (26.2) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 11.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 12.2 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 6 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 9.3 |

| Source: Weather Atlas [74] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 688 | — | |

| 1850 | 2,367 | 244.0% | |

| 1860 | 2,832 | 19.6% | |

| 1870 | 5,016 | 77.1% | |

| 1880 | 9,890 | 97.2% | |

| 1890 | 18,080 | 82.8% | |

| 1900 | 17,114 | −5.3% | |

| 1910 | 19,945 | 16.5% | |

| 1920 | 18,749 | −6.0% | |

| 1930 | 12,831 | −31.6% | |

| 1940 | 12,927 | 0.7% | |

| 1950 | 26,433 | 104.5% | |

| 1960 | 33,956 | 28.5% | |

| 1970 | 29,312 | −13.7% | |

| 1980 | 24,382 | −16.8% | |

| 1990 | 24,832 | 1.8% | |

| 2000 | 25,478 | 2.6% | |

| 2010 | 24,649 | −3.3% | |

| Est. 2019 | 24,118 | [4] | −2.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[75] | |||

As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 25,478 people, 11,016 households, and 5,463 families residing in Key West. The population density was 4,285.0 inhabitants per square mile (1,653.3/km2). There were 13,306 housing units at an average density of 2,237.9 per square mile (863.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 84.94% White, 9.28% African American, 0.39% Native American, 1.29% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 1.86% from other races, and 2.18% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino persons of any race were 16.54% of the population.

There were 11,016 households, out of which 19.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.7% were married couples living together, 8.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 50.4% were classified as non-families. Of all households, 31.4% were made up of individuals, and 8.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.23 and the average family size was 2.84.

The population was spread out, with 16.0% under the age of 18, 8.4% from 18 to 24, 37.1% from 25 to 44, 26.7% from 45 to 64, and 11.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 122.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 126.0 males.

The median income for a household was $43,021, and the median income for those classified as families was $50,895. Males had a median income of $30,967 versus $25,407 for females. The per capita income for the city was $26,316. About 5.8% of families and 10.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 11.5% of those under age 18 and 11.3% of those age 65 or over.

The ancestries most reported in 2000 were English (12.4%), German (12.2%), Irish (11.3%), Italian (6.8%), American (6.0%) and French (3.6%).

The number of families (as defined by the Census Bureau) declined dramatically in the last four decades of the 20th century. In 1960 there were 13,340 families in Key West, with 42.1% of households having children living in them. By 2000 the population had dwindled to 5,463 families, with only 19.9% of households having children living in them.[76]

As of 2000, 76.66% spoke English as a first language, while Spanish was spoken by 17.32%, 1.06% spoke Italian, 1.02% spoke French, and German spoken as a mother tongue was at 0.94% of the population. In total, other languages spoken besides English made up 25.33% of residents.[77]

"Conchs"

Many of the residents of Key West were immigrants from the Bahamas, known as Conchs (pronounced "conks"'), who arrived in increasing numbers after 1830. Many were sons and daughters of Loyalists who fled to the nearest Crown soil during the American Revolution.[78] In the 20th century many residents of Key West started referring to themselves as Conchs, and the term is now generally applied to all residents of Key West. Some residents use the term "Conch" (or, alternatively, "Saltwater Conch") to refer to a person born in Key West, while the term "Freshwater Conch" refers to a resident not born in Key West but who has lived in Key West for seven years or more.[79] The true original meaning of Conch applies only to someone with European ancestry who immigrated from the Bahamas, however. It is said that when a baby was born, the family would put a conch shell on a pole in front of their home.

Many of the black Bahamian immigrants who arrived later lived in Bahama Village, an area of Old Town next to the Truman Annex.

Cuban presence

Key West is closer to Havana (106 miles or 171 kilometres)[7] than it is to Miami (130 mi, 210 km).[9] In 1890, Key West had a population of nearly 18,800 and was the biggest and richest city in Florida.[80] Half the residents were said to be of Cuban origin, and Key West regularly had Cuban mayors, including the son of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, father of the Cuban Republic, who was elected mayor in 1876.[81] Cubans were actively involved in reportedly 200 factories in town, producing 100 million cigars annually. José Martí made several visits to seek recruits for Cuban independence starting in 1891 and founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party during his visits to Key West.[81]

Key West was flooded with refugees during the Mariel Boatlift. Refugees continue to come ashore and, on at least one occasion, most notably in April 2003, flew hijacked Cuban Airlines planes into the city's airport.[82]

Government and politics

Key West Government is governed via the mayor-council system. The city council is known as the city commission. It consists of six members each elected from individual districts. The mayor is elected in a citywide vote.

Mayors

Mayors of Key West have reflected the city's cultural and ethnic heritage. Among its mayors are the first Cuban mayor and one of the first openly gay mayors. One mayor is also famous for having water-skied to Cuba.[83]

Military presence

NAS Key West, Boca Chica and the Truman Annex have been the home of U.S. ships, submarines, Pegasus-class hydrofoils and Fighter Training Squadrons like the VF101 detachment. NAS Key West is still a training facility for top gun pilots.[84]

Key West has had a military presence since 1823, shortly after its purchase by Simonton in 1822. John W. Simonton lobbied the U.S. government to establish a naval base on Key West, both to take advantage of its strategic location and to bring law and order to the Key West town. On March 25, 1822, naval officer Matthew C. Perry sailed the schooner Shark to Key West and planted the U.S. flag claiming the Keys as United States property. In 1823 A naval base was established to protect shipping merchants in the lower keys from pirates. The original base is now known as Mallory Square.

Key West was always an important military post, since it sits at the northern edge of the deepwater channel connecting the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico (the southern edge 90 miles [140 km] away is Cuba) via the Florida Straits. Because of this, Key West since the 1820s had been dubbed the "Gibraltar of the West". Fort Taylor was initially built on the island. The Navy added a small base from which the USS Maine sailed to its demise in Havana at the beginning of the Spanish–American War.

Key West Naval Air Station

At the beginning of World War II the Navy increased its presence from 50 to 3,000 acres (20 to 1,214 hectares), including all of Boca Chica Key's 1,700 acres (690 ha) and the construction of Fleming Key from landfill. The Navy built the first water pipeline extending the length of the Keys, bringing fresh water from the mainland to supply its bases.[85] At its peak 15,000 military personnel and 3,400 civilians were at the base. Included in the base are:

- Naval Air Station Key West – This is the main facility on Boca Chica, where the Navy trains its pilots. Staff are housed at Sigsbee Park. In 2006 there were 1,650 active-duty personnel; 2,507 family members; 35 Reserve members; and 1,312 civilians listed at the base. In the 1990s the Navy worked out an agreement with the National Park Service to stop sonic booms near Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas. Many of the training missions are directed at the Marquesas "Patricia" Target 29 nautical miles (54 km) due west of the base. The target is a grounded ship hulk 306 feet (93 m) in length that is visible only at low tide. Bombs are not actually dropped on the target.

- Truman Annex – The area next to Fort Taylor became a submarine pen and was used for the Fleet Sonar School. President Harry S. Truman was to make the commandant's house his winter White House. The Fort Taylor Annex was later renamed the Truman Annex. This portion has largely been decommissioned and turned over to private developers and the city of Key West. There are still a few government offices there, however, including the new NOAA Hurricane Forecasting Center. The Navy still owns its piers.

- Trumbo Annex – The docking area on what had been the railroad yard for Flagler's Overseas Railroad is now used by the Coast Guard.

Media

Key West is part of the Miami-Fort Lauderdale television market. It is served by rebroadcast transmitters in Key West and Marathon that repeat the Miami-Fort Lauderdale stations. Comcast provides cable television service. DirecTV and Dish Network provide Miami-Fort Lauderdale local stations and national channels.

The Key West area has 11 FM radio stations, 4 FM translators, and 2 AM stations. WEOW 92.7 is the home of The Rude Girl & Molly Blue, a popular morning zoo duo; Bill Bravo is the afternoon host. SUN 99.5 has Hoebee and Miss Loretta in the p.m. drive. Island 107.1 FM is the only locally owned, independent FM station in Key West, featuring alternative rock music and community programs.

The Florida Keys Keynoter and the Key West Citizen are published locally and serve Key West and Monroe County. The Southernmost Flyer, a weekly publication printed in conjunction with the Citizen, is produced by the Public Affairs Department of Naval Air Station Key West and serves the local military community. Key West the Newspaper (known locally as The Blue Paper due to its colorful header) is a local weekly investigative newspaper, established in 1994 by Dennis Cooper, taken over in 2013 as a fully digital publication by Arnaud and Naja Girard.[86]

Education

Monroe County School District operates public schools in Key West.

District-operated elementary schools serving the City of Key West include Poinciana Elementary School, which is located on the island of Key West, and Gerald Adams Elementary School, which is located on Stock Island.[87] District-operated middle and high schools include Horace O'Bryant School, a former middle school that now operates as a K–8 school, and the Key West High School. All of Key West is zoned to Horace O'Bryant School for grades 6-8 and to Key West High School for grades 9–12. Sigsbee Charter School is a K–8 school, sanctioned by the District and serving predominantly military dependent children as well as children from the community at large.[88] Admission to Sigsbee Charter School is limited and the waiting list is managed by a lottery system.[89] Key West Montessori Charter School is a district-sanctioned charter school on Key West Island.[90]

The main campus of Florida Keys Community College is located in Key West.[91]

Notable people

Born in Key West

- Vic Albury, MLB pitcher

- Bronson Arroyo, baseball player[92]

- Stepin Fetchit, comedian[93]

- George Mira, football player[94]

- John Patterson, MLB second baseman

- Quincy Perkins, filmmaker[95]

- David Robinson, basketball player[96]

- Shane Spencer, MLB outfielder

- Randy Sterling, MLB pitcher

- David Wolkowsky, real estate developer and preservationist[97]

Residents and visitors

- John James Audubon, naturalist, painter, ornithologist[98]

- Elizabeth Bishop, poet[99]

- Judy Blume, children's author[100]

- Jimmy Buffett, musician[101]

- Eric Carle, author[102]

- David Allan Coe, musician[103]

- Tom Corcoran, author

- Sandy Cornish, civic leader, former slave[104]

- Paul Cotton, musician

- John Dewey, philosopher and psychologist[105]

- Mel Fisher, treasure hunter[106]

- Robert Fuller, actor[107]

- Khalil Greene, MLB shortstop

- Ernest Hemingway, author[108][109][110]

- Winslow Homer, landscape painter[111]

- Calvin Klein, fashion designer[110][112]

- Mike Leach, college football coach [113]

- Alison Lurie, novelist

- Stephen Mallory, U.S. senator[114]

- Kelly McGillis, actress[108]

- James Merrill, poet

- Diana Nyad, First person to swim from Cuba to Key West, FL without a shark cage.[115]

- John Dos Passos, novelist[116]

- Boog Powell, baseball player[117][118]

- Thomas Sanchez, author

- Shel Silverstein, author, cartoonist and musician[119]

- Wallace Stevens, poet

- Keith Strickland, musician, songwriter and founding member of The B-52s

- Michel Tremblay, Canadian playwright

- Harry S. Truman, U.S. president[108]

- Dick Vermeil, former Super Bowl Champion NFL Coach[120]

- Tennessee Williams, author[109]

- Stuart Woods, author[121]

See also

Notes

- Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- Official records for Key West were kept at the Weather Bureau in downtown from January 1871 to February 1958, and at Key West Int'l since March 1958. For more information, see ThreadEx.

References

- "2010 Census U.S. Gazetteer Files - Places National". United States Census Bureau. n.d. Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Key West City Information: Regional Setting". February 4, 2006. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "ACME Mapper". Mapper.acme.com. ACME Labs.

Zoom out, drag map until the center pointer is on the Cuban coast, zoom in and adjust position, then click the 'Markers' button at bottom right of map. Units can be changed via the 'Options' button.

- "Latitude/Longitude Distance Calculator". Nhc.noaa.gov. National Hurricane Center.

Coordinates used for Key West (the Whitehead Spit): 24.54410 (N), 81.80486 (W), and for Cuba (a headland just west of Santa Cruz del Norte): 23.18375 (N), 82.0003 (W).

- "Distance from Miami, FL to Key West, FL". check-distance.com. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- Lizette Alvarez (December 24, 2012). "Key West Looks at Identity as It Plots Tourism Future". The New York Times. Retrieved December 25, 2012.

- Viele, John (1996). The Florida Keys: A History of the Pioneers. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press. pp. 3, 7. ISBN 978-1-56164-101-7.

- "Exploring Florida Documents: Key West: General History and Sketches". Fcit.usf.edu. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- Windhorn, Stan & Langley, Wright 1973. Yesterday's Key West

- Viele, John (1996). The Florida Keys: A History of the Pioneers. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press. pp. 13–16. ISBN 978-1-56164-101-7.

- Jerry Wilkinson. "History of Key West". Florida Keys History Museum. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- "Exploring Florida Documents: Key West: The Municipality". Florida Center for Instructional Technology. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- Browne, Jefferson B. (1912). "Chapter 1: General History and Random Sketches". Key West: The Old and the New. St. Augustine, FL: The Record Company Printers and Publishers. p. 7.

- "Loading". Archived from the original on October 24, 2010. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Federal Writers' Project (1939). Florida: A Guide to the Southernmost State. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 199. ISBN 9781603540094. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- A Chronological History of Key West A Tropical Island City, Stephen Nichols, 3rd ed.

- June Keith, June Keith's Key West & The Florida Keys: A Guide to the Coral Islands (5th ed.: Palm Island Press, 2014), p. 8.

- "Marker Details - Key West Historic Markers Project". www.keywesthistoricmarkertour.org. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- "National Weather Service Forecast Office - WFO Key West, Florida". September 16, 2006. Archived from the original on September 16, 2006. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- "Solares Hill". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- "First person to swim from Cuba to Florida without a shark cage or fins". Guinnessworldrecords.com. Guinness World Records. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- Press, Associated (September 11, 2013). "Diana Nyad defends Cuba-to-Florida swim as skeptics question use of gear". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 28, 2016.

- CNN Staff (September 1, 2013). "Diana Nyad's Cuba to Florida swim breaks one record". Cnn.com. Cable News Network. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- "Old Island Restoration Foundation's Key West Oldest House Museum and Garden". oirf.org. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- "About the Audubon House – Audubon House & Tropical Gardens". Audubon House & Tropical Gardens. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- "Fort Zachary Taylor". Fortzacharytaylor.com. Archived from the original on December 12, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- "Key West Art & Historical Society | Fort East Martello". Kwahs.org. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- "Tower History". Keywestgardenclub.com. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- "Key West Art & Historical Society | Lighthouse & Keeper's Quarters". Kwahs.org. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- "Key West Museum History | Truman Little White House". Trumanlittlewhitehouse.com. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form for Dr. Joseph Y. Porter House". Npgallery.nps.gov. National Park Service. June 4, 1973. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form for Eduardo H. Gato House". Npgallery.nps.gov. National Park Service. April 11, 1973. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- "Marker Details - Key West Historic Markers Project". Keywesthistoricmarkertour.org. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- "Marker Details - Key West Historic Markers Project". Keywesthistoricmarkertour.org. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- "Key West Cemetery". Keywesttravelguide.com. Key West Travel Guide, LLC. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- "Key West Cemetery Map & Self-Guided Tour". Keywesttravelguide.com. Key West Travel Guide, LLC. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- US Army Quartermaster (1913). US Army Quartermaster Report of 1912. US War Department. p. 511. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- "Key West Resorts – Waldorf Astoria Casa Marina Hotel – FL". Casamarinaresort.com. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- "Monroe County, FL – Official Website – Higgs Beach". Monroecounty-fl.gov. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- Key West History Archived December 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- O'Brien, Bridget. "Southernmost Point Buoy In Key West Shines Again". Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- O'Hara, Timothy. "Key West Library All Set to Turn 60". Key West Citizen.

- Klingener, Nancy (April 18, 2018). "Power Magnet: Key West's Long History Of Presidential Visits". Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- "Truman Little White House | Key West Museum History". www.trumanlittlewhitehouse.com. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- "Truman Little White House | Truman Key West visits". trumanlittlewhitehouse.com. Truman Little White House. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- "Truman Little White House | Media center". trumanlittlewhitehouse.com. Truman Little White House. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- Google (January 27, 2015). "314 Simonton Street, Key West, Fl" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- McIver, Stuart B. (2002). Hemingway's Key West. Pineapple Press Inc. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-56164-241-0.

- "Sloppy Joe's...Yesterday". sloppyjoes.com/history. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- Google (January 27, 2015). "907 Whitehead Street, Key West, Fl" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- "Hemingway – The Legend". hemingwayhome.com. Hemingway Home. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- Google (January 27, 2015). "1431 Duncan Street, Key West, Fl" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- Google (January 27, 2015). "5901 College Road, Key West, Fl" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- Dundy, Elaine (June 9, 2001). "Our men in Havana". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- A Chronological History of Key West: A Tropical Island City, Stephen Nichols

- Filosa, Gwen (October 6, 2013). "Anti-study side: 'No means no'". The Key West Citizen. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- Filosa, Gwen (February 2, 2014). "New process for city to alter channel". The Key West Citizen. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- City of Key West Port Operations Office

- "Koppen climate map". Archived from the original on July 6, 2011.

- "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- Gutelius, Scott; Stone, Marshall; Varner, Marcus (2003), True Secrets of Key West Revealed!, Key West: Eden Entertainment Limited, ISBN 978-0-9672819-4-0

- Key West Citizen "New commissioners' trial by wind and flood" October 27, 2005

- Key West Citizen October 25, 2005, pp 1-2, 6

- Key West Citizen "Flooded cars litter the Keys" October 27, 2005

- "Station Name: FL KEY WEST INTL AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- "WMO Climate Normals for KEY WEST/INTL, FL 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- "Average Weather for Key West, FL - Temperature and Precipitation". Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- "Key West, Florida, USA - Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Census 2000: Households of Key West, Florida" (PDF). Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- "Data Center Results". Mla.org. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- Windhorn, Stan & Langley, Wright Yesterday's Key West p.13

- The key to restoring conchs Archived March 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine – URL September 21, 2006

- "History of Key West". Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- "DOS EXILIOS". Amigospais-guaracabuya.org.

- "April 2003". Keysso.net.

- "St. Petersburg Times - Google News Archive Search".

- "Naval Air Station Key West". Naval Air Station Key West. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- Enright, Tracy J. "SOFIA - Paper - Geology and Hydrogeology of the Florida Keys". Sofia.usgs.gov. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- "Key West FL Newspapers & News Media - ABYZ News Links".

- "Monroe County School District - School Maps". Keysschools.schoolfusion.us. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- "Sigsbee Charter School: About Us". Sigsbee.org. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- "Sigsbee Charter School: Registration Facts". Sigsbee.org. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- "Key West Montessori Charter School: About Our School". Keywestmontessori.com. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- "Florida Keys Community College". U.S. News and World Reports. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014.

- Shpigel, Ben. "Arroyo Leaves the Mets Flailing." The New York Times. June 20, 2006.

- Strausbaugh, John. "Stepin Fetchit: The Life and Times of Lincoln Perry." International Herald Tribune. December 12, 2005.

- Effrat, Louis. "Mira, Heralded Quarterback, Also Sought as Big League Pitcher; Miami star here for festivities All-America Back Puts Off Thoughts of Turning Pro to Finish College." The New York Times. December 7, 1962.

- Archived December 29, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Whiteside, Larry. "Taking center stage David Robinson has wasted no time in winning star status." The Boston Globe. January 12, 1990.

- "Real-Estate-Entrepreneur.com". July 14, 2012. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- Famous Key West residents Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- de León, Concepción (November 13, 2019). "Literary Nonprofit Buys Elizabeth Bishop's Key West Home". The New York Times. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- Dominus, Susan (May 18, 2015). "Judy Blume Knows All Your Secrets". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- Pooley, Eric. "Still Rockin' In Jimmy Buffett's Key West Margaritaville." TIME. August 17, 1998.

- Ulaby, Neda (June 12, 2019). "A Very Happy 50th Birthday To 'The Very Hungry Caterpillar'". Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- Sandra Brennan (1997). All Music Guide to Country. Michael Erlewine. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-87930-475-1.

- "Freed Slave Sandy Cornish Gets a Marker in Cemetery". South Florida Times. February 19, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- Psycopaedìa. Psicopolis.com

- Pace, Eric. "Mel Fisher, 76, a Treasure Hunter Who Got Rich Undersea." The New York Times. December 21, 1998.

- Collura, Joe (September 1, 2017). "Robert Fuller". Quad-City Times. Davenport, Iowa. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- Nickell, Patti. "Key West: The fun begins where the road ends." Lexington Herald-Leader. September 21, 2008.

- "Key West fest honors Tennessee Williams." CNN. February 23, 2003.

- "Key West: The Last Resort." TIME. February 19, 1979.

- Federal Writers' Project (1939). Florida: A Guide to the Southernmost State. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 159. ISBN 9781603540094. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- Calvin Klein House – Key West Archived January 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "Ex-Texas Tech coach Mike Leach expects return to coaching". ESPN. March 18, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- Crankshaw, Joe. "Water District Chanded S. Florida." Miami Herald. September 29, 1985. Page 2TC.

- Alvarez, Lizette (September 2, 2013). "Nyad Completes Cuba-to-Florida Swim". The New York Times.

- Dos Passos, John (1966). The best times: an informal memoir. New American Library.

- Distel, Dave. "Baseball Bat, Fishing Pole Both Valuable to Boog." Los Angeles Times News Service (via St. Petersburg Times.) August 15, 1970.

- Burke, J. Wills. The Streets of Key West. Pineapple Press. 200.

- Bellido, Susana. "Shel Silverstein, 66, Children's book author." The Philadelphia Inquirer. May 11, 1999.

- Chris Tomasson. "Dick Vermeil led Eagles to first Super Bowl, hoping for different outcome on Sunday." Pioneer Press. 2 February 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- Stuart Woods Official Website. stuartwoods.com Archived June 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Barnett, William C. "Inventing the Conch Republic: The Creation of Key West as an Escape from Modern America", Florida Historical Quarterly (2009) 88#2 pp. 139–172 in JSTOR

- Boulard, Garry. "'State of Emergency': Key West in the Great Depression". Florida Historical Quarterly (1988): 166–183. in JSTOR

- Gibson, Abraham H., "American Gibraltar: Key West during World War II", Florida Historical Quarterly, 90 (Spring 2012), 393–425.

- Levy, Philip. "'The Most Exotic of Our Cities': Race, Place, Writing, and George Allan England's Key West". Florida Historical Quarterly (2011): 469–499. in JSTOR

- Ogle, Maureen. Key West: History of an island of dreams (University Press of Florida, 2003)