Philadelphia International Airport

Philadelphia International Airport (IATA: PHL, ICAO: KPHL, FAA LID: PHL) is the primary airport serving Philadelphia. The airport serves 31.7 million passengers annually, making it the 20th busiest airport in the United States. In 2019, PHL served 33,018,886 passengers, the most in the airport's history. The airport is located 7 mi (11 km) from the city's downtown area and has 25 airlines that offer nearly 500 daily departures to more than 130 destinations worldwide.[3]

Philadelphia International Airport | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | City of Philadelphia | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | Philadelphia Department of Commerce, Division of Aviation | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | Delaware Valley | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Philadelphia / Tinicum Township, Pennsylvania, United States | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hub for | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Focus city for | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | Eastern (UTC−05:00) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | Eastern Daylight Time (UTC−04:00) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 36 ft / 11 m | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 39°52′19″N 075°14′28″W | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www.phl.org | ||||||||||||||||||||||

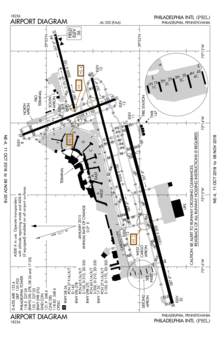

| Maps | |||||||||||||||||||||||

FAA diagram | |||||||||||||||||||||||

PHL  PHL  PHL | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2019) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Philadelphia International Airport (PHL) is located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and is the largest airport in the state.[4] It is the fifth-largest hub for American Airlines and its primary hub for the Northeastern United States, as well as its primary European and transatlantic gateway. Additionally, the airport is a regional cargo hub for UPS Airlines and a focus city for the ultra low-cost airline Frontier Airlines.

The airport has service to cities in the United States, Canada, the Caribbean, Latin America, Europe, and the Middle East. As of summer 2019, there are flights from the airport to 140 destinations, 102 domestic and 38 international. Most of the airport property is in Philadelphia proper. The international terminal and the western end of the airfield are in Tinicum Township, Delaware County. PHL covers 2,302 acres (932 ha) and has 4 runways.[2]

Philadelphia International Airport is important to Philadelphia, its metropolitan region and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The Commonwealth's Aviation Bureau reported in its Pennsylvania Air Service Monitor that the total economic impact made by the state's airports in 2004 was $22 billion. In 2017, PHL commissioned a new economic impact report. The report found PHL alone accounted for $15.4 billion in activity with over 96,000 direct and indirect jobs with $5.4 Billion in total earnings.[5] In 2018, the airport was ranked by J.D. Power as one of the "worst large airports in the U.S."[6]

History

Starting in 1925, the Pennsylvania National Guard used the present airport site (known as Hog Island) as a training airfield. The site was dedicated as the "Philadelphia Municipal Airport" by Charles Lindbergh in 1927, but it had no proper terminal building until 1940; airlines used Camden Central Airport in nearby Camden, New Jersey. Once Philadelphia's terminal was completed (on the east side of the field) American, Eastern, TWA and United moved their operations here.

In 1947 and 1950 the airport had runways 4, 9, 12 and 17, all 5400 ft or less. In 1956 runway 9 was 7284 ft; in 1959 it was 9499 ft and runway 12 was closed. Not much changed until the early 1970s, when runway 4 was closed and 9R opened with 10500 ft.

On June 20, 1940 the airport's weather station became the official point for Philadelphia weather observations and records by the National Weather Service.[7]

World War II use

During World War II the United States Army Air Forces used the airport as a First Air Force training airfield.[8][9][10]

Beginning in 1940, Rising Sun School of Aeronautics of Coatesville performed primary flight training at the airport under contract to the Air Corps. After the Pearl Harbor Attack, the I Fighter Command Philadelphia Fighter Wing provided air defense of the Delaware Valley area from the airport. Throughout the war, various fighter and bomber groups were organized and trained at Philadelphia airport and assigned to the Philadelphia Fighter Wing before being sent to advanced training airfields or being deployed overseas. Known units assigned were the 33d, 58th, 355th and 358th Fighter Groups.

In June 1943 I Fighter Command transferred jurisdiction of the airport to the Air Technical Service Command (ATSC). ATSC established a sub-depot of the Middletown Air Depot at the airport. The 855th Army Air Forces Specialized Depot unit repaired and overhauled aircraft and returned them to active service, and the Army Air Forces Training Command established the Philco Training School on January 1, 1943, which trained personnel in radio repair and operations.

In 1945 the Air Force reduced its use of the airport and it was returned to civil control that September.

Airline use

Philadelphia Municipal became Philadelphia International in 1945, when American Overseas Airlines began direct flights to Europe. (For a short time AOA's flights skipped the New York stop; that was probably Philadelphia's only international nonstop until Pan Am tried nonstops to Europe in 1961.) A new terminal opened in December 1953; the oldest parts of the present terminal complex (B and C) were built in the late '50s.

The April 1957 OAG shows 30 weekday departures on Eastern, 24 TWA, 24 United, 18 American, 16 National, 14 Capital, 6 Allegheny and 3 Delta. To Europe, five Pan Am DC-6Bs a week via Idlewild and Boston and two TWA 749As a week via Idlewild; one TWA flight continued to Ceylon. Eastern and National had nonstops to Miami, but the TWA 1049G to LAX that started in 1956 was the only nonstop beyond Chicago. The first scheduled jets were TWA 707s in summer 1959.[11]

Terminal B/C modernization was completed in 1970, Terminal D opened in 1973 and Terminal E in 1977; the $300 million expansion[12] was designed by Arnold Thompson Associates, Inc. and Vincent G. Kling & Associates.[13]

In the 1980s PHL hosted several hubs. The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 allowed regional carrier Altair Airlines to create a small hub at PHL using Fokker F-28s. Altair began in 1967 with flights to cities such as Rochester, New York, Hartford, Connecticut and to Florida until it ceased operations in November 1982. In the mid-1980s Eastern Air Lines opened a hub in Concourse C. The airline declined in the late 1980s and sold aircraft and gate leases to Chicago-based Midway Airlines. Midway operated its Philadelphia hub until it ceased operation in 1991. During the 1980s US Airways (then called USAir) built a hub at PHL.

US Airways became the dominant carrier at PHL in the 1980s and 1990s and shifted most of its hub operations from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia in 2003. As of 2013 PHL was US Airways' largest international hub and its second-largest hub overall behind Charlotte.[14] PHL became an American Airlines hub after it completed its merger with US Airways in 2015 and remains one of the airline's biggest hubs, offering an average of 420 departing flights per day to over 100 destinations. In recent years, American has opted to continue expanding at PHL while downsizing its hub at JFK in New York due to greater slot availability, lower operation costs in Philadelphia, and its greater network of connecting flights.

In July 1999 the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) and several U.S. federal government agencies selected a route for the connecting ramps from Interstate 95 to the Terminal A-West complex, then under development; the agency tried to avoid the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum. K/B Fund II, the owner of the International Plaza complex, formerly the Scott Paper headquarters Scott Plaza, objected to the proposed routing, saying it would interfere with International Plaza development. It entered a filing in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit to challenge the proposed routing.[15] In 2000, the airport attempted to acquire the complex for $90 million but Tinicum Township commissioners stopped the deal from going forward, citing concerns of a loss of tax revenue for the township and the Interboro School District, which serves Tinicum, as well as noise pollution concerns.[16]

In 2002 construction on the controversial new entrance ramps went forward. The new ramps eliminated the traffic signal and stop intersections previously encountered by northbound I-95 motorists who had to use Route 291 to the airport. The project consisted of six new bridges, more than 4,300 linear feet of retaining walls, and 7.7 lane miles of new pavement. The project also included new highway lighting, overhead sign structures, landscaping and the paving of Bartram Avenue. Also under the project, PennDOT resurfaced I-95 between Route 420 and Island Avenue and built a truck enforcement and park-and-ride facility.[17] In 2003 Terminal A-West opened, with a 1,500-space parking garage. Construction of the terminal was funded by airport revenue bonds sold by the Philadelphia Authority for Industrial Development.[18]

By 2005 two studies dealt with expanding runway capacity at PHL: the Runway 17–35 Extension Project EIS and the PHL Capacity Enhancement Program EIS.[19] Completed in May 2009,[20] the Runway 17-35 Extension Project extended runway 17–35 to a length of 6,500 ft (2,000 m), extending it at both ends and incorporating the proper runway safety areas. Other changes made with the Runway 17–35 Extension Project included additional taxiways and aprons, relocation of perimeter service roads, and modifications to nearby public roads.

The status of Philadelphia as an international gateway and major hub for American Airlines and the growth of Southwest Airlines and other low-cost carriers have increased passenger traffic to record levels in the mid-2000s; in 2004 28,507,420 passengers flew through Philadelphia, up 15.5% over 2003.[21] In 2005, 31,502,855 passengers flew through PHL, marking a 10% increase since 2004.[22] In 2006, 31,768,272 passengers travelled through PHL, a 0.9% increase.[23]

At 12,000 feet (3,658 meters) in length, runway 9R/27L (previously 10,506 feet) is the longest civil runway in Pennsylvania.

Facilities

Philadelphia International Airport has seven terminal buildings, divided into six lettered concourses, with 126 gates total. As of late November 2015, it is possible to walk to each terminal post security without leaving the secure side. A shuttle bus, located post security, transport passengers from terminal F to terminal c, and terminal A. The shuttle transfers passengers from terminal A to terminal F, or terminal C to Terminal F. There is a large shopping/dining area between Concourses B and C. There are no luggage storage facilities at the airport. PHL offers over 120 shopping and dining locations throughout its facilities. There are options ranging from grab and go food to sit down restaurants.[24]

Terminal A

.jpg)

Terminal A is divided into two sections, east and west. Terminal A West has 13 gates, whilst Terminal A East has 11 gates. Terminal A West has a modern and innovative design, made by Kohn Pedersen Fox, Pierce Goodwin Alexander & Linville and Kelly/Maiello.[25] Opened in 2003 as the new international terminal, it is now home to American (domestic and international), British Airways, Lufthansa, Icelandair and Qatar Airways. It offers a variety of international dining options. International Arrivals (except from locations with Customs preclearance) arrive at gates in both Terminal A east and west and are processed at the Terminal A West arrival building.

Terminal A East, originally the airport's international terminal, is now used by Aer Lingus and American domestic and international flights as well as international arrivals for Frontier Airlines. A-East is well maintained and recently received an upgrade to its baggage claim facilities. Most of the gates in this terminal are equipped to handle international arrivals and the passengers are led to the customs facility in Terminal A West. It opened in 1990. The security entrance was significantly enlarged in 2012.

There are 3 lounges along the corridor between Terminal A East and A West; an American Airlines Admirals Club, British Airways Galleries Lounge and American Express Centurion Lounge. The east terminal also contains an Admirals Club. There is also a children's play area located in the east terminal.

Terminals B and C

Terminals B and C have 15 and 14 gates respectively. They are the two main terminals used by American. They were renovated at a cost of $135 million in 1998, which was designed by DPK&A Architects, LLP.[26] They are connected by a shopping mall and food court named the Philadelphia Marketplace. Remodeling has begun in the gate areas, although these cosmetic changes will not solve the space problems at many of the gates. Overall, the facilities are fairly modern and dining options on the concourses are also available. They are the oldest terminals and opened in 1953. There is an American Airlines Admirals Club located in the B/C connector.

Terminal D

Terminal D has 16 gates; it opened in 1973. The terminal was upgraded in late 2008 with a new concourse connecting to Terminal E while providing combined security, a variety of shops and restaurants and a link between Baggage Claims D and E. This is the inverse of the connector between Terminals B and C, which comprises a combined ticket hall but separate security facilities. Terminal D is home to Air Canada, Alaska Airlines, Delta, and United. This terminal is connected to the shopping area of Terminals B/C through a post-security walkway. The terminal contains a United Club and a Delta Sky Club.

Terminal E

.jpg)

Terminal E has 17 gates. It is home to Frontier, JetBlue, Southwest, and Spirit. It opened in 1977. Terminal E houses a USO lounge available for all members of the military and their family.

Terminal F

Terminal F has 38 gates. The terminal is a regional terminal used by American Eagle flights. It includes special jet bridges that allow passengers to board regional jets without walking on the apron. Opened in 2001, Terminal F is the second newest terminal building at PHL. It was designed by Odell Associates, Inc. and The Sheward Partnership.[27] An American Airlines Admirals Club is located above the central food court area of Terminal F.

When Terminal F opened in 2001, it had 10,000 sq ft (930 m2) of space for concessions.[28]

Ground transportation

SEPTA Regional Rail's Airport Line serves stations at Terminals A, B, C, D, and E. The four stations are Airport Terminal A East/West, Airport Terminal B, Airport Terminals C & D, and Airport Terminals E & F. The stations are next to the baggage claim at each terminal with escalator and elevator access from each terminal's skywalk. The Airport Line connects to Center City Philadelphia, other SEPTA trains, Amtrak trains, and NJ Transit trains at 30th Street Station. The Airport Line runs through Center City Philadelphia to Glenside, PA; many weekday trains and half of the weekend trains continue to Warminster, PA on the Warminster Line. The Airport Line runs 5:00 a.m. to 12:00 a.m. daily, with trains every 30 minutes. The ride from the airport to Center City Philadelphia takes 25 minutes.[29][30]

Philadelphia International Airport has road access from an interchange with I-95, which heads north toward Center City Philadelphia and south into Delaware County. PA 291 heads northeast from the airport area and provides access to and from I-76 (Schuylkill Expressway).[31] Rental cars are available through a number of companies; each operates a shuttle bus between its facility and the terminals. As part of the airport's expansion plan, the airport plans to construct a consolidated rental car facility. Taxis and ride-sharing services both serve the airport.[32][33]

SEPTA has various bus routes to the airport: Route 37 (serving South Philadelphia and Chester Transportation Center), Route 108 (serving 69th Street Transportation Center and the UPS air hub), and Route 115 (serving Delaware County Community College and Darby Transportation Center). As a benefit to students, local schools including The University of Pennsylvania, Villanova University, Swarthmore College, Haverford College and Saint Joseph's University traditionally operate transportation shuttles to the airport during heavy travel periods such as spring and Thanksgiving breaks.

Airlines and destinations

Passenger

Cargo

| Airlines | Destinations | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| 21 Air | Miami, Orlando | |

| Amerijet International | Sacramento | |

| DHL Aviation | Cincinnati | |

| FedEx Express | Boston, Indianapolis, Memphis, Pittsburgh, Washington–Dulles Seasonal: Hartford | |

| FedEx Feeder | Newark | |

| Kalitta Air | Seasonal: Ontario | |

| UPS Airlines | Albany, Albany (GA), Atlanta, Boston, Buffalo, Chicago–O'Hare, Chicago/Rockford, Cologne/Bonn, Columbia (SC), Des Moines, Detroit, East Midlands, Harrisburg, Hartford, Hong Kong, London–Stansted, Louisville, Manchester (NH), Miami, Minneapolis/St. Paul, New York–JFK, Oakland, Ontario, Orlando, Paris–Charles de Gaulle, Pittsburgh, Portland (OR), Raleigh/Durham, Richmond, San Jose (CA), Tampa Seasonal: Providence |

Statistics

Top destinations

| Rank | City | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Orlando, Florida | 753,160 | American, Frontier, Southwest, Spirit |

| 2 | Atlanta, Georgia | 624,610 | American, Delta, Frontier, Southwest, Spirit |

| 3 | Chicago–O'Hare, Illinois | 534,250 | American, United |

| 4 | Boston, Massachusetts | 525,020 | American, Delta, JetBlue |

| 5 | Dallas/Fort Worth, Texas | 444,280 | American, Frontier, Spirit |

| 6 | Charlotte, North Carolina | 423,190 | American, Frontier |

| 7 | Los Angeles, California | 386,088 | Alaska, American, Spirit |

| 8 | Fort Lauderdale, Florida | 352,680 | American, JetBlue, Southwest, Spirit |

| 9 | Denver, Colorado | 343,160 | American, Frontier, Southwest, United |

| 10 | Miami, Florida | 340,740 | American, Frontier |

| Rank | Airport | Passengers | Annual Change | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | London–Heathrow, United Kingdom | 455,273 | American, British Airways | |

| 2 | Toronto–Pearson, Canada | 299,897 | Air Canada, American | |

| 3 | Cancún, Mexico | 264,338 | American, Frontier | |

| 4 | Dublin, Ireland | 237,301 | Aer Lingus, American | |

| 5 | Montego Bay, Jamaica | 200,434 | American, Frontier | |

| 6 | Punta Cana, Dominican Republic | 189,860 | American, Frontier | |

| 7 | Montréal–Trudeau, Canada | 185,128 | Air Canada, American | |

| 8 | Doha, Qatar | 180,218 | Qatar | |

| 9 | Frankfurt, Germany | 178,888 | Lufthansa | |

| 10 | Rome–Fiumicino, Italy | 152,228 | American |

Top airlines

| Rank | Airline | Passengers | Annual Change | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | American Airlines | 22,529,080 | 68.23% | |

| 2 | Southwest Airlines | 2,130,422 | 6.45% | |

| 3 | Delta Air Lines | 2,076,897 | 6.29% | |

| 4 | Frontier Airlines | 2,037,998 | 6.17% | |

| 5 | United Airlines | 1,231,571 | 3.73% |

Annual traffic

| Year | Passengers | Growth | Year | Passengers | Growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 6,606,482 (through June) | 2010 | 30,775,961 | ||

| 2019 | 33,018,886 | 2009 | 30,669,564 | ||

| 2018 | 31,691,956 | 2008 | 31,834,725 | ||

| 2017 | 29,585,754 | 2007 | 32,211,439 | ||

| 2016 | 30,155,090 | 2006 | 31,768,272 | ||

| 2015 | 31,444,403 | 2005 | 31,495,385 | ||

| 2014 | 30,740,242 | 2004 | 28,507,420 | ||

| 2013 | 30,504,112 | 2003 | 24,671,075 | ||

| 2012 | 30,252,816 | 2002 | 24,799,470 | ||

| 2011 | 30,839,175 | 2001 | 24,553,310 | - |

Accidents and incidents

- On January 14, 1951, Flight 83 crashed upon landing at Philadelphia from Newark. The aircraft skidded off the runway, crashed through a fence and came to rest in a ditch. During the incident, the left wing broke off, rupturing the gas tanks and setting the plane on fire. There were seven fatalities in all. Frankie Housley, the lone stewardess on Flight 83, led ten passengers to safety but lost her life trying to save an infant.

- On February 7, 2006, a UPS Airlines Douglas DC-8 cargo plane suffered an in-flight cargo fire and made an emergency landing at Philadelphia International Airport after filling with smoke.[59] There were no injuries other than smoke inhalation affecting the crew, but the plane burned on the ground for hours into the night, though most of the cargo survived, the aircraft was a total loss, with multiple holes burned through the roof skin. According to the NTSB,[60] the firefighting crew did not have adequate training on using their skin-piercing extinguishing equipment and not knowing how to open the main cargo door, attempted to force the handle and broke the latch, rendering the door unopenable. There were also difficulties in obtaining the cargo manifest to determine what if any hazardous materials were on board, due to confusion about protocol. However, despite these failings, the airport staff, including the firefighting staff, managed the incident successfully without injury or major disruption of the airport. The NTSB suspected lithium ion batteries were the source of ignition and made recommendations for more stringent rules and restrictions on their air transport, especially on passenger aircraft (unlike this one). For a cause of the incident, the NTSB focused on the delayed indication of fire by the required onboard fire detection system and criticized the standards to which such systems are tested, noting that the tests use an empty cargo hold and do not represent the real-world performance of the detection systems with the hold full of cargo, which significantly changes the flow patterns of hot air and smoke. The crew and air traffic control personnel were found to have behaved properly (with minor exceptions) and not to be at fault for the incident or its outcome.

- On March 13, 2014, US Airways Flight 1702, an Airbus A320-214, rotated then aborted takeoff and as a result suffered a tailstrike and a nose landing gear collapse. The aircraft then continued down runway 27L coming to a stop off to the left of the runway. None of the 149 passengers and 5 crew members suffered life-threatening injuries. However the aircraft saw substantial damage and was later written off and scrapped. The accident was found to be pilot error and since neither the captain nor first officer has flown commercially.

- On April 17, 2018, Southwest Airlines Flight 1380, a Boeing 737-700 en route from New York to Dallas, suffered an engine failure on its left engine. Debris from the engine struck the aircraft's fuselage and a side window. The window failed, causing a rapid depressurization of the aircraft, which made an emergency descent and diverted to land at Philadelphia International Airport. One passenger died after being partially ejected from the failed window. Seven others were injured and treated locally at the airport.

Potential Impacts of Climate Change

Located near the water in a tidal estuary of the Delaware River, Philadelphia International Airport is considered highly vulnerable to future flooding as a consequence of sea level rise caused by global climate change.[61] A 2015 report by the Philadelphia Mayor's Office of Sustainability projected sea level rise of approximately two feet by 2050.[62] Combined with an increased frequency of extreme weather events like hurricanes and storm surges, there is a high likelihood of the airport being inundated in the coming years.[63] Some have advocated for relocating the airport entirely.[64]

See also

References

- "Aviation Activity Report City of Philadelphia Month and Year - December 2017" (PDF). PHL Airport. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 14, 2018. Retrieved February 13, 2018.

- FAA Airport Master Record for PHL (Form 5010 PDF), effective February 1, 2018.

- "About Us". Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- Airports Council International Archived October 8, 2006, at the Wayback Machine Final statistics for 2005 traffic movements

- "Manta - The Place for Small Business". Manta.

- Hermann, Adam. "Philadelphia International Airport ranked one of the worst large airports in the U.S." Philly Voice. Archived from the original on August 16, 2019. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- "Threaded Extremes". Archived from the original on May 19, 2006. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- "Air Force History Index -- Search".

- Maurer, Maurer (1983). Air Force Combat Units of World War II. Maxwell AFB, Alabama: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-89201-092-4.

- Maurer, Maurer (1969), Combat Squadrons of the Air Force, World War II, Air Force Historical Studies Office, Maxwell AFB, Alabama. ISBN 0-89201-097-5

- TWA's 707 to LAX is not in the OAG for 15 July; it is in TWA's timetable for 2 August.

- "1960s -1970s". Archived from the original on June 22, 2012.

- "Not the Master Planner". Engineering News-Record. McGraw-Hill. 195 (14): 15. October 1975. Retrieved June 15, 2012.

- Blumenthal, Jeff (January 22, 2013). "US Airways Renews Lease at Philadelphia International Airport, Eyes Improvements". Philadelphia Business Journal. Archived from the original on January 26, 2013. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- Klimkiewicz, Joann. "New Airport Terminal Runs Into Legal Fight A Court Challenge By A Property Owner Could Delay The Opening Of Us Airways' $325 Million Terminal One. Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine" Philadelphia Inquirer. April 28, 2000. Retrieved on August 22, 2013.

- Klimkiewicz, Joann. "Airport Is Denied Purchase Of Land Phila. International Wants To Expand. Tinicum Fears Noise Pollution And The Loss Of Tax Revenues. Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine" Philadelphia Inquirer. February 23, 2000. Retrieved on August 22, 2013.

- Hogate, Jayanne (June 28, 2002). "Pennsylvania Gov. Schweiker Cuts Ribbon to Open New I-95 Ramps To Philadelphia International Airport". Pennsylvania Office of the Governor. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- Gelbart, Marcia (April 27, 2003). "New gateway to the world The international terminal opens Friday". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- "Capacity Enhancement Program EIS". Archived from the original on May 6, 2005. Retrieved August 21, 2005.

- "Tinicum crying foul on new airport runway". Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- "Passenger Traffic 2004 FINAL". Airports Council International. Archived from the original on January 3, 2006. Retrieved January 3, 2005.

- "Airport Continues to Attract Record Numbers of Passengers" (Press release). Philadelphia Airport System. August 15, 2005. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2005.

- "Passenger Traffic 2006 FINAL". Airports Council International. July 18, 2007. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved July 30, 2007.

- "PHL Fast Facts" (PDF). phl.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- "Transportation". Archived from the original on August 12, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- "Philadelphia International Airport (PHL/KPHL), PA". Airport Technology. Archived from the original on June 12, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- Belden, Tom (April 2, 1998). "Us Airways, Phila. Agree on Adding Two Terminals Overseas, Commuter Flights The Focus of A$400 Million Plan". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- "Philadelphia International Airport – Press Release". Archived from the original on February 5, 2009.

- "Welcome to SEPTA - Philadelphia International Airport". SEPTA. Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- "Airport Line schedule" (PDF). SEPTA. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 24, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- Metro Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Map) (19th ed.). 1"=2000'. ADC Map. 2006. ISBN 978-0-87530-777-0.

- "Ride with Uber - Philadelphia International Airport (PHL)". Uber. Archived from the original on April 11, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- "Lyft at Philadelphia International Airport". Lyft. Archived from the original on April 11, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- "Flight Schedules". Archived from the original on September 25, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Flight Schedules". Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- "American Airlines Adds More Capacity in Montana With New Service to National Parks". Yahoo! Finance. August 29, 2019.

- Liu, Jim (May 10, 2020). "American Airlines plans A321neo Philadelphia – Reykjavik service from June 2021". Routesonline. Informa Markets. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- "Flight schedules and notifications". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- Martin, Jenna (February 20, 2020). "American Airlines to launch new route from CLT to Pennsylvania this summer". Charlotte Business Journal. American City Business Journals.

- "Timetables". Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- "FLIGHT SCHEDULES". Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "FLIGHT SCHEDULES". Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- "Frontier Airlines Boosts Cincinnati Service and Restores 6 Popular Routes" (Press release). Frontier Airlines. June 16, 2020.

- "Frontier Airlines Boosts Philadelphia Service with 3 New Routes, Added Frequency" (Press release). Frontier Airlines. June 3, 2020.

- "Frontier". Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- "Flight Schedule". Icelandair. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- "JetBlue Will Add 30 New Routes, Launch Mint at Newark" (Press release). JetBlue Airways. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- "JetBlue Airlines Timetable". Archived from the original on July 13, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- "Timetable - Lufthansa Canada". Lufthansa. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- "Route Map/Timetable Search". Archived from the original on March 28, 2017. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- "Check Flight Schedules". Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Where We Fly". Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- "Route Map & Flight Schedule". Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- "Timetable". Archived from the original on January 28, 2017. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- "RITA - BTS - Transtats". Retrieved August 13, 2020.

- "BTS Air Carriers : T-100 International Market (All Carriers)". Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- "PHL Fast Facts" (PDF). Philadelphia International Airport. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 4, 2019. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Fire Forces UPS Plane to Make Emergency Landing". CNN. February 8, 2006. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- "Inflight Cargo Fire United Parcel Service Company Flight 1307 McDonnell Douglas CS-8-71F, N748UP". National Transportation Safety Board. February 7, 2006. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- "Pennsylvania and the Surging Sea | Surging Seas: Sea level rise analysis by Climate Central". Climate Central. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- "Growing Stronger: Toward a Climate-Ready Philadelphia | Office of Sustainability". City of Philadelphia. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Kummer, Frank. "As climate changes and seas rise, Philadelphia International Airport is in the crosshairs". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- "Philly Needs to Move the Airport Before It's Underwater". Philadelphia Magazine. October 27, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Philadelphia International Airport. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Philadelphia International Airport. |

- Philadelphia International Airport (official web site)

- FAA Airport Master Record for PHL (Form 5010 PDF)

- Wings Over Philadelphia – Abundant Information Regarding PHL

- Pennsylvania Bureau of Aviation: Philadelphia International Airport

- Food and Shops at PHL

- PHL-Citizens Aviation Watch

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective August 13, 2020

- Resources for this airport:

- AirNav airport information for KPHL

- ASN accident history for PHL

- FlightAware airport information and live flight tracker

- NOAA/NWS weather observations: current, past three days

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KPHL

- FAA current PHL delay information