Holmes County, Mississippi

Holmes County is a county in the U.S. state of Mississippi; its western border is formed by the Yazoo River and the eastern border by the Big Black River. The western part of the county is within the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta. As of the 2010 census, the population was 19,198.[1] Its county seat is Lexington.[2] The county is named in honor of David Holmes, territorial governor and the first governor of the state of Mississippi and later United States Senator for Mississippi.[3] A favorite son, Edmond Favor Noel, was an attorney and state politician, elected as governor of Mississippi, serving from 1908 to 1912.

Holmes County | |

|---|---|

| |

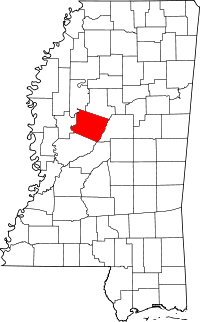

Location within the U.S. state of Mississippi | |

Mississippi's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 33°07′N 90°05′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1833 |

| Named for | David Holmes |

| Seat | Lexington |

| Largest city | Durant |

| Area | |

| • Total | 765 sq mi (1,980 km2) |

| • Land | 757 sq mi (1,960 km2) |

| • Water | 7.9 sq mi (20 km2) 1.0% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 19,198 |

| • Estimate (2018) | 17,622 |

| • Density | 25/sq mi (9.7/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 2nd |

| Website | holmescountyms |

Cotton was long the commodity crop; before the Civil War, its cultivation was based on slave labor and the majority of the population was made up of black slaves. Planters generally developed their properties along the riverfronts. After the war, many freedmen acquired land in the bottomlands of the Delta by clearing and selling timber, but most lost their land during difficult financial times, becoming tenant farmers or sharecroppers.[4] With an economy based on agriculture, the county had steep population declines from 1940 to 1970, due to mechanization of farm labor, and the second wave of the Great Migration, as African Americans migrated from the Deep South especially to West Coast cities, where jobs were plentiful in the buildup of the defense industry.

Some African Americans had reacquired land in Holmes County in the 1940s under the New Deal programs. By 1960, Holmes County's 800 independent black farmers owned 50% of the land, more such farmers than elsewhere in the state.[5] They were integral members of the Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s. In 1967, eight of ten black candidates to run for local county office were landowning farmers; they were the first African Americans to run for office in the county since Reconstruction. Holmes had more candidates running for offices for the Freedom Democratic Party than did any other county.[6]

Robert G. Clark, Jr., a teacher in Holmes County, was elected as state representative in 1967, the first black to be elected to state government in the 20th century. He served as the only African American in the state house until 1976. He continued to be re-elected to the state legislature from Holmes County until 2003. In the late 20th century, he was elected to the first of three terms as Speaker of the state House.

History

The western border of the county is formed by the Yazoo River; it is next to the Mississippi Delta, and shares its characteristics. The eastern border is formed by the Big Black River and the eastern part has hills. The county was developed for cotton plantations in the antebellum era before the American Civil War, with most properties of the period located along the riverfronts for transportation access. Due to the plantation economy and reliance on slave labor, the county was majority black before the Civil War.

"According to U.S. Census data, the 1860 Holmes County population included 5,806 whites, 10 "free colored" and 11,975 slaves. By the 1870 census, the white population had increased about 6% to 6,145, and the "colored" population had increased about 10% to 13,225."[7] After the war, many freedmen and white migrants went to Holmes County and other parts of the Mississippi Delta, where they developed the bottomlands behind the riverfront properties, clearing and selling timber in order to buy their own lands.[8][9] Workers were also attracted to the Delta area by higher than usual wages on the plantations, which had a labor shortage in the transition to a free labor economy.

By the turn of the 20th century, a majority of the landowners in the Delta counties were black. Effectively blacks were disenfranchised by the new constitution of 1890; the loss of political power added to their economic problems associated with the financial Panic of 1893. Unable to gain credit, many of the first generations of African-American landowners lost their properties by 1920. In this period, they were also competing for land with the better-funded timber and railroad companies. Afterward, the blacks were forced to become sharecroppers or tenant farmers.[8][9]

The period after Reconstruction and through the early 20th century had the highest incidence of whites lynching blacks. Holmes County had 10 documented lynchings in the period from 1877 to 1950, most around the turn of the 20th century.[10] Two lynchings took place in the county seat of Lexington, Mississippi in the 1940s.

White planters continued to recruit labor in the area, as freedmen wanted to work on their own account. The first Chinese immigrant laborers entered the Delta in the late 1870s. From 1900-1930, additional Chinese immigrants arrived in Mississippi, including some to Holmes County. They worked hard to leave field labor and often became merchants, especially becoming grocers of small stores in the rural Delta towns. As their socioeconomic status changed, the Chinese Americans carved out a niche "between black and white", gaining admission to white schools for their children through court challenges. With the decline of small towns, most Chinese Americans moved to larger cities through the 20th century. In Mississippi, the number of ethnic Chinese has increased overall in the state through 2010, although it is still small in total - fewer than 5,000.[11][12][13]

During the New Deal, the Roosevelt administration worked through the Farmers Home Administration to provide low-interest loans in order to increase black land ownership. They also established a co-op cotton gin to be used by farmers in the project. In Holmes County, numerous blacks became landowners through this program in the 1930s and 1940s. They were fiercely independent and later were among strong supporters of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, even as whites kept a grip on economic and political power through banks, police and the county courthouse.[14] Although there had been outmigration, the population of the county in 1960 was still 42% black.[15]

The USDA Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service (ASCS) (established under another name in the 1930s) carried out its programs on a county-wide level. County boards were elected annually by farmers to work on local programs, and to make approval of loans to farmers and similar issues. Although blacks made up a large portion of landowners in Holmes County, they were disenfranchised from voting and excluded from participating on the board. They were generally deprived of potential benefits through this program, as part of the pattern of racial discrimination against them.

Beginning in the World War II period, the population of Holmes County declined markedly from its peak of 1940; through 1970 thousands left, with most African Americans going to the West Coast or in Midwestern cities in the second wave of the Great Migration, taking jobs in the booming defense industry. From 1950 to 1960, for instance, some 6,000 blacks left the county,[16] a decline of nearly 19%. But in 1960 the county was still 72% black, with a total population of 27,100.[16]

Even with these problems, in 1960 Holmes County had more independent black farmers than did any other county in the state: 800 black farmers owned 50% of the land in the county.[5] They were among those who initiated the civil rights movement, particularly farmers of Mileston, where the soil was rich. They invited organizers of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to come to Mileston to help them take action. The majority of the first fourteen blacks who attempted to register to vote on April 9, 1963 were landowners.[14] Holmes County became the site of renewed organizing of grassroots efforts for African-American civil rights, with people designated as responsible for its Beats and precincts.[16]

In 1954 some whites had formed the White Citizens Council, expressly to oppose desegregation of public schools after the United States Supreme Court decision that year in Brown v. Board of Education, finding segregation to be unconstitutional. They raised funds to support whites-only schools, and conducted economic boycotts of blacks suspected of civil rights activism, as well as social and political pressure against whites who crossed them. Among their targets in the latter category was Hazel Brannon Smith, publisher and editor of two local papers. For three years, her customers resisted the Council's effort to boycott her and cut out her advertising; the Council started a rival newspaper to try to take away her business. Opponents arranged for her husband to be fired from his job as county hospital administrator, and a group firebombed two of her papers. She received a Pulitzer Prize for journalism in 1964 for her editorials about the civil rights movement during this period.[15]

The Freedom Democratic Party was organized in 1964 to work on black voter registration and education, and continued after passage of civil rights laws. For instance, where white Democratic Party officials had defined the very large Lexington precinct, which held the majority of population, the county chapter of the FDP organized its own sub-precincts within it in order to communicate better with its community.[16] The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were important but had to be implemented on the local level, where resistance to black voting continued to be strong, sometimes becoming violent.

The FDP worked with residents to register African-American voters and encourage them to vote. As resistance continued by white officials, in November 1965 a federal registrar was assigned to the county, based on residents' petitions about the circuit clerk's discrimination over a 4-month period. After this, 2,000 black voters were registered in two months.[17]

The FDP also worked with local people to run for positions on the ASCS board. In the fall of 1965, six black farmers were elected to the county board, with four as alternates. This gave them a voice in determining how local programs would run.[17] Discrimination in USDA programs was continuing and widespread, as shown by the settlement of the class-action suit, Pigford v. Glickman in 1999, with payments continuing into the 21st century.[18][19]

In 1966 many communities in the county concentrated on setting up the new federal Head Start program for young children. The FDP continued to work with other communities on correcting unfair hiring at factories and unequal administration of welfare, as well as trying to end discrimination at eating places.[20] From 1966 on, the FDP registered an increasing number of black voters and gained their participation in elections. By November 1967, nearly 6,000 new voters were registered in the county.

In 1967 black farmers and landowners, who had been part of the Movement since the early 1960s, comprised eight of the ten candidates who ran for local and state offices: Thomas C. "Top Cat" Johnson,[21] Ed Noel McGaw, Jr.; Ward Montgomery; John Malone; Willie James Burns; John Daniel Wesley; Griffin McLaurin, and Ralthus Hayes.[5][21] McLaurin was elected as constable of one of the beats in the county.[5]

Robert G. Clark (born 1928) and Robert Smith, both teachers, had joined the Movement in 1966 and ran for state representative and county sheriff, respectively. Clark was a member of a landowning family in Ebenezer; he had a master's degree and had nearly finished his PhD from University of Michigan.[22] He won a seat as the first and only black elected in 1967 to the Mississippi House of Representatives. By 2000, Clark had been re-elected to eight four-year terms in the state house and had been elected as Speaker three times since 1992.[23] It was not until 1976 that another African American was elected to the state legislature, but then the number increased. Several were elected to local offices in Holmes County well before that.

Whites have also left the county since the mid-20th century because of declining work opportunities. Agribusinesses have bought up large tracts of land, and the number of independent farmers has declined markedly. By 2010, the total population was less than half that of 1940. Still largely rural, Holmes County in the 21st century has problems associated with poverty and limited access to health care; it has the lowest life expectancy of any county in the United States, for both men and women.[24]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 765 square miles (1,980 km2), of which 757 square miles (1,960 km2) is land and 7.9 square miles (20 km2) (1.0%) is water.[25]

Major highways

Adjacent counties

- Carroll County (north)

- Attala County (east)

- Yazoo County (south)

- Humphreys County (west)

- Leflore County (northwest)

National protected areas

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 9,452 | — | |

| 1850 | 13,928 | 47.4% | |

| 1860 | 17,791 | 27.7% | |

| 1870 | 19,370 | 8.9% | |

| 1880 | 27,164 | 40.2% | |

| 1890 | 30,970 | 14.0% | |

| 1900 | 36,828 | 18.9% | |

| 1910 | 39,088 | 6.1% | |

| 1920 | 34,513 | −11.7% | |

| 1930 | 38,534 | 11.7% | |

| 1940 | 39,710 | 3.1% | |

| 1950 | 33,301 | −16.1% | |

| 1960 | 27,096 | −18.6% | |

| 1970 | 23,120 | −14.7% | |

| 1980 | 22,970 | −0.6% | |

| 1990 | 21,604 | −5.9% | |

| 2000 | 21,609 | 0.0% | |

| 2010 | 19,198 | −11.2% | |

| Est. 2018 | 17,622 | [26] | −8.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[27] 1790-1960[28] 1900-1990[29] 1990-2000[30] 2010-2013[1] | |||

From 1940 until 1970, the county had major declines in population as many blacks left the state in the Great Migration. Whites have also left as economic opportunities were limited in the rural county. As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 19,198 people living in the county, less than half than at the peak of population in 1940. 83.4% were Black or African American, 15.6% White, 0.2% Asian, 0.1% Native American, 0.1% of some other race and 0.6% of two or more races. 0.7% were Hispanic or Latino (of any race).

As of the census[31] of 2000, there were 21,609 people, 7,314 households, and 5,229 families living in the county. The population density was 29 people per square mile (11/km²). There were 8,439 housing units at an average density of 11 per square mile (4/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 78.66% Black or African American, 20.47% White, 0.12% Native American, 0.15% Asian, 0.07% from other races, and 0.52% from two or more races. 0.90% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

According to the census[31] of 2000, the largest ancestry groups that residents of Holmes County identified were African 78.66%, English 11.4%, and Scots-Irish 5%.

There were 2,314 households out of which 11.00% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 24.10% were married couples living together, 21.20% had a female householder with no husband present, and 18.50% were non-families. 16.30% of all households were made up of individuals and 12.10% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.86 and the average family size was 3.48.

In the county, the population was spread out with 32.10% under the age of 18, 12.40% from 18 to 24, 24.80% from 25 to 44, 18.30% from 45 to 64, and 12.40% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30 years. For every 100 females there were 87.30 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 79.30 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $17,235, and the median income for a family was $21,757. Males had a median income of $23,720 versus $17,883 for females. The per capita income for the county was $10,683. About 35.90% of families and 41.10% of the population were below the poverty line, including 52.30% of those under age 18 and 36.40% of those age 65 or over.

Holmes County has the lowest per capita income in Mississippi and the 41st lowest in the United States.

Politics

During and following the Reconstruction era in the 19th century, African Americans had supported the Republican Party, which achieved emancipation of slaves and granted freedmen full citizenship and constitutional rights. Following the effective disenfranchisement of blacks in 1890 by the state's new constitution with restrictions on voter registration, blacks were excluded from politics in Mississippi; other southern states repeated this model, so they were disenfranchised across the former Confederacy. However, the Republican Party retained influence through political appointments, and people struggled to control these within each southern state.[32]

Perry Wilbon Howard (born in Ebenezer in 1877) was one of about two dozen African-American attorneys among the second generation of freedmen in the state. After passing the bar, he set up a practice in the capital of Jackson, where he worked for about fifteen years. Active in the Republican Party, he was a delegate to national conventions from 1912 to 1960, representing his constituents to the national party. Although he moved to Washington, DC, where he was partner in a prominent black law firm, Howard was elected as Republican National Committeeman from Mississippi in 1924, and retained control of this position (and patronage appointments) until 1960. He was appointed in 1923 to a national position in the Office of the Attorney General in the administration of Warren G. Harding, retaining it until resigning under President Herbert Hoover in 1928.[32]

Since the civil rights years and gains of enforcement in voting rights in the late 1960s, most African-American voters, who constitute a large majority in the county, have voted strongly for Democratic candidates in Presidential and Congressional elections. The last Republican presidential candidate to win a majority in the county was Barry Goldwater in 1964, at a time when nearly all African Americans in the county and state were still disenfranchised by the state's constitution and discriminatory practices. In 2008, Democrat Barack Obama won 81 percent of the county's vote, as seen by the adjacent table.

Holmes is part of Mississippi's 2nd congressional district, which is represented by Democrat Bennie Thompson.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 16.2% 1,309 | 82.8% 6,689 | 1.0% 78 |

| 2012 | 15.5% 1,435 | 84.1% 7,812 | 0.4% 41 |

| 2008 | 18.0% 1,714 | 81.4% 7,765 | 0.7% 64 |

| 2004 | 23.4% 1,961 | 75.9% 6,366 | 0.7% 56 |

| 2000 | 26.1% 1,937 | 73.4% 5,447 | 0.5% 38 |

| 1996 | 24.0% 1,536 | 73.6% 4,720 | 2.4% 155 |

| 1992 | 28.2% 1,694 | 68.0% 4,092 | 3.8% 228 |

| 1988 | 33.7% 2,737 | 65.8% 5,350 | 0.5% 39 |

| 1984 | 35.4% 3,102 | 64.5% 5,641 | 0.1% 10 |

| 1980 | 32.3% 2,693 | 65.5% 5,463 | 2.2% 180 |

| 1976 | 33.9% 2,438 | 64.1% 4,616 | 2.1% 149 |

| 1972 | 47.2% 3,158 | 51.7% 3,459 | 1.0% 69 |

| 1968 | 7.0% 520 | 52.4% 3,881 | 40.6% 3,008 |

| 1964 | 96.6% 3,115 | 3.4% 110 | |

| 1960 | 17.7% 455 | 24.5% 628 | 57.8% 1,484 |

| 1956 | 10.1% 215 | 40.8% 872 | 49.2% 1,052 |

| 1952 | 47.8% 1,305 | 52.2% 1,423 | |

| 1948 | 1.1% 24 | 2.7% 61 | 96.2% 2,139 |

| 1944 | 5.9% 122 | 94.1% 1,954 | |

| 1940 | 1.8% 37 | 98.2% 2,041 | |

| 1936 | 0.6% 12 | 99.4% 1,885 | |

| 1932 | 2.4% 45 | 97.1% 1,799 | 0.4% 8 |

| 1928 | 6.3% 134 | 93.7% 2,004 | |

| 1924 | 7.3% 92 | 92.7% 1,173 | |

| 1920 | 6.9% 69 | 91.6% 917 | 1.5% 15 |

| 1916 | 1.9% 21 | 96.8% 1,070 | 1.3% 14 |

| 1912 | 0.5% 5 | 95.3% 936 | 4.2% 41 |

Education

- Colleges

- Holmes Community College (Goodman)

- Elementary and secondary schools

During the segregation years, when black public schools were historically underfunded, Lexington was the location in 1918 of the founding of what became known as Saints Academy, a private school for black students affiliated with the Church of God in Christ. After Arenia Mallory became principal in 1926, she expanded the school to serve more students, ultimately in grades 1-12. Conducting fund raising outside the state, she promoted a strong academic education with Christian discipline, and her school was nationally known. She led it until her death in 1977, ultimately establishing an associated junior college. The school continued until 2006.

During the period of integration of public schools in Mississippi in the late 1960s, many white parents in the majority-black Delta enrolled their children in newly established private segregation academies, as in Holmes County. But statewide most white children remained in public schools.[34] In Holmes County, blacks had become well-organized, but in other areas they lost control of their schools, with administrations often dominated by whites, resulting in different problems during and after integration.[35]

- Public Schooling

- Private schools

- Central Holmes Christian School (Lexington) (formerly Central Holmes Academy, founded as a segregation academy)[36][37][38]

- Old Dominion Christian School

- Pillow Academy in unincorporated Leflore County, near Greenwood, enrolls some students from Holmes County.[39] It originally was founded as a segregation academy.[40]

- Closed Schools

- East Holmes Academy A segregation academy that made national news in 1989 for offering to forfeit a game because the other school had a black player. Closed 2006.

Media

The county newspaper is the Holmes County Herald. It was established in 1959 as the weekly paper of the county chapter of the White Citizens Council, founded to resist integration of public schools and other elements of the civil rights movement.[5] Specifically it was founded to compete with The Lexington Advertiser owned by local white publisher Hazel Brannon Smith, whose politics the White Citizens Council disliked. The Council arranged for Smith's husband to be fired from his job as county hospital administrator. Brannon Smith was eventually forced out of the business by white boycotts of her newspapers and the firebombing of one paper in Jackson, Mississippi.

The Herald published the names of African Americans who took action for civil rights in order to bring economic and political pressure against them. For instance, in April 1963 it published interviews and the names of 14 blacks who attempted to register to vote at the county courthouse in Lexington. The county circuit clerk published the names weekly of persons who tried to register to vote, thus identifying them for reprisals.[5] Known or suspected activists were fired from jobs and evicted from rental housing as the Council tried to suppress the civil rights movement. The Herald was bought by an independent person in 1970.

Communities

Notable people

- Homer Casteel, politician and public servant; lieutenant governor 1920 to 1924; member of the Mississippi Public Service Commission from 1936 to 1952.

- Robert G. Clark, Jr., teacher, coach and politician; in 1967 he was elected to the state legislature as the first African-American member since Reconstruction; he was elected to eight consecutive four-year terms and as Speaker of the state House in 1992, 1996 and 2000.[23]

- Perry Wilbon Howard, attorney and Republican Party National Committeeman, was appointed to a national position in the Department of Justice under President Warren G. Harding, serving into Herbert Hoover's administration. He was the highest-ranking African American in government.

- Arenia Mallory, principal and president of Saints Academy, she had a more than 50-year career with this school, which she built into an academically successful, nationally known private school for black children during the segregation years, also expanding to a junior college. A leader in African-American women's national organizations, she served in the John F. Kennedy administration.

- Edmond Favor Noel, Governor of Mississippi, 1908–1912, was born to a planter family in Lexington. He became an attorney and politician, serving in the state house and then the state senate both before and after his tenure as governor. He improved education in the state.

- Edmond F. Noel Sr (1916-1986), born in Lexington and reared in Jackson, was a Howard University and Fisk University graduate, a World War II veteran, and the first African-American physician in Denver, Colorado to be granted staff hospital privileges (he and his wife moved there in 1949).[41][42]

- Edmond "Eddie" F. Noel (1926-1990), was born and lived in Lexington. An African-American veteran of World War II, he killed three white men in January 1954, including a deputy sheriff, and evaded capture for three weeks, making national news. He was hunted by numerous men, dogs, and even observers in planes. He turned himself in to the court, where the judge ordered a mental evaluation. Noel was committed by the court to the state mental institution, where he was held for more than a decade. He was released in 1970 and lived his last 20 years with his family in Fort Wayne, Indiana.[43][44]

- Hazel Brannon Smith, publisher and journalist, in 1935 purchased The Durant News and The Lexington Advertiser in Lexington; she published them for decades and was noted in the region for her fair coverage and later support of civil rights. She opposed the White Citizens Council, which conducted an advertising boycott against her papers. She won the Pulitzer Prize for journalism in 1964 for her editorials on civil rights, the same year her paper, then The Northside Reporter in Jackson, was firebombed. She was forced out of business.

In popular culture

Carolyn Haines, an American mystery writer, sets many of her novels in Holmes County and other parts of the Mississippi Delta.[45]

See also

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 159.

- "Dwindling Black Farmers Fight Formidable Odds for Future : Agriculture: Small operations, particularly those owned by African-Americans, are disappearing. Their numbers have declined from one-seventh in 1920 to less than 1% today". Los Angeles Times. 1990-12-30. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- Sue (Lorenzi) Sojourner, "Got to Thinking: How the Black People of Holmes Co., Mississippi Organized Their Civil Rights Movement", Praxis International, Exhibit, Duluth, MN

- Sojourner with Reitan (2013), Thunder of Freedom, p. 242

- "HOLMES COUNTY, MISSISSIPPI/ LARGEST SLAVEHOLDERS FROM 1860 SLAVE CENSUS SCHEDULES and SURNAME MATCHES FOR AFRICAN AMERICANS ON 1870 CENSUS", compiled by Tom Blake, April 2003, accessed 8 June 2015

- John Otto Solomon, The Final Frontiers, 1880–1930: Settling the Southern Bottomlands, Westport: Greenwood Press, 1999, p.50

- John C. Willis, Forgotten Time: The Yazoo-Mississippi Delta after the Civil War, Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2000

- Lynching in America, 2nd edition Archived 2018-06-27 at the Wayback Machine, Supplement by County, p. 5

- Loewn, James W. The Mississippi Chinese: Between Black and White. Prospect Heights, Illinois: Waveland Press, 1988, 2nd edition.

- O'Brien, Robert W. "Status of the Chinese in the Mississippi Delta." Social Forces (March 1941), pp. 386-390

- Quan, Robert Seto. Lotus Among the Magnolias: The Mississippi Chinese. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1982

- Map: Holmes County, Mississippi, The Legacy of SNCC and the Fight for Voting Rights, One Person/One Vote website, 2015, Duke University, accessed 10 June 2015

- Hazel Brannon Smith, "Bombed, Burned, and Boycotted", Alicia Patterson Foundation, 1984, accessed 28 November 2015

- Sue-Henry Lorenzi, "Holmes County Freedom Democratic Party Executive Members' Handbook," August 1966, Southern Freedom Movement Documents 1951-1968/ Listed by Kind of Document, Civil Rights Movement Veterans website

- Sojourner with Reitan (2013), Thunder of Freedom, p. 289

- Tadlock Cowan and Jody Feder, "The Pigford Case: USDA Settlement of a Discrimination Suit by Black Farmers", Congressional Research Service, 29 May 2013, accessed 9 January 2016

- Susan A. Schneider, Food, Farming, and Sustainability, Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2011 (discussing Pigford v. Glickman, 185 F.R.D. 82 (D.D.C. 1999))

- Sue (Lorenzi) Sojourner and Cheryl Reitan, Thunder of Freedom: Black Leadership and the Transformation of 1960s Mississippi, Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2013. ISBN 0813140935

- Sojourner with Reitan (2013), Thunder of Freedom, pp. 228-230

- Sojourner with Reitan (2013), Thunder of Freedom, p. 266

- "Robert G. Clark, 26 October 2000 (video)", The Morris W. H. (Bill) Collins Speaker Series, Mississippi State University, accessed 10 June 2015

- "Life expectancy in U.S. trails top nations". CNN. 16 June 2011.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Neil R. McMillen, “Perry W. Howard, Boss of Black-and-Tan Republicanism in Mississippi, 1924-1960”, The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 48, No. 2 (May, 1982), pp. 205-224 at JSTOR (subscription required)

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- Bolton (2005), The Hardest Deal of All, p. 109

- Bolton (2005), The Hardest Deal of All, pp. 178-179

- Bolton, Charles C. The Hardest Deal of All: The Battle Over School Integration in Mississippi, 1870-1980. University Press of Mississippi, 2005, p. 136. ISBN 1604730609, 9781604730609

- Cobb, James Charles. The Most Southern Place on Earth: The Mississippi Delta and the Roots of Regional Identity. Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 0195089138, 9780195089134.

- "Contact Us Archived 2013-10-03 at the Wayback Machine." Central Holmes Christian School. Retrieved on March 23, 2013. "130 Robert E. Lee Street Lexington, MS 39095"

- "Profile of Pillow Academy 2010-2011 Archived 2001-12-01 at the Library of Congress Web Archives." Pillow Academy. Retrieved on March 25, 2012.

- Lynch, Adam (18 November 2009). "Ceara's Season". Jackson Free Press. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- "The Origin of Rose Medical Center, Denver, Colorado", Colorado Health Care History

- Martin, Claire (5 February 2008). "Activist Led the Way to School Integration". Denver Post.

- Bill Minor, "Strange true story about Eddie Noel", DeSoto Times, 11 August 2010, accessed 25 November 2015

- Allie Povall, The Time of Eddie Noel, Comfort Publishing, 2010

- Haines, Carolyn. Smarty Bones.

Further reading

- Charles E. Cobb, Jr. On the Road to Freedom: A Guided Tour of the Civil Rights Trail (2008)

- Sue (Lorenzi) Sojourner and Cheryl Reitan, Thunder of Freedom: Black Leadership and the Transformation of 1960s Mississippi, Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2013.

- Jan Whitt, Burning Crosses and Activist Journalism: Hazel Brannon Smith and the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement (2009)

- Charles Reagan Wilson, "Chinese in Mississippi: An Ethnic People in a Biracial Society," Mississippi History Now, November 2002.

- Youth Of The Rural Organizing and Cultural Center, Minds Stayed on Freedom: The Civil Rights Struggle In The Rural South — An Oral History. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1991.

External links

- Holmes County Official webpage

- Holmes County Herald

- Library of Congress - The Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection - Photos of life in 1930s-era Holmes County

- Oliver Laughland, "In the poorest county, in America’s poorest state, a virus hits home: 'Hunger is rampant,'" The Guardian, April 6, 2020.

- Sue-Henry Lorenzi, "Holmes County Freedom Democratic Party Executive Members' Handbook," August 1966, Southern Freedom Movement Documents 1951-1968/ Listed by Kind of Document, Civil Rights Movement Veterans website