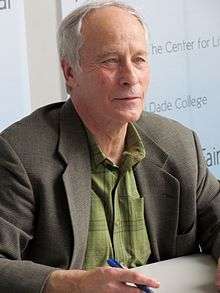

Richard Ford

Richard Ford (born February 16, 1944) is an American novelist and short story writer. His best-known works are the novel The Sportswriter and its sequels, Independence Day, The Lay of the Land and Let Me Be Frank With You, and the short story collection Rock Springs, which contains several widely anthologized stories. Ford received the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1996 for Independence Day. Ford's novel Wildlife was adapted into a 2018 film of the same name.

Richard Ford | |

|---|---|

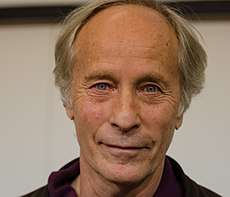

Ford at the Göteborg Book Fair 2013 | |

| Born | February 16, 1944 Jackson, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer |

| Nationality | United States |

| Education | Michigan State University, University of California, Irvine |

| Period | 1976–present |

| Genre | Literary fiction |

| Literary movement | Dirty realism |

Early life

Ford was born in Jackson, Mississippi, the only son of Parker Carrol and Edna Ford. Parker was a traveling salesman for Faultless Starch, a Kansas City company. Of his mother, Ford said, "Her ambition was to be, first, in love with my father and, second, to be a full-time mother." When Ford was eight years old, his father had a severe heart failure, and thereafter Ford spent as much time with his grandfather, a former prizefighter and hotel owner in Little Rock, Arkansas, as he did with his parents in Mississippi.[1] Ford's father died of a second heart attack in 1960. In Jackson, Ford lived across the street from the home of author Eudora Welty. [2]

Ford's grandfather had worked for a railroad. At the age of 19, before deciding to attend college, Ford began work on the Missouri Pacific train line as a locomotive engineer's assistant, learning the work while doing the job.[3]

Ford received a B.A. degree from Michigan State University. Having enrolled to study hotel management, he switched to English. After graduating, he taught junior high school in Flint, Michigan, and enlisted in the United States Marine Corps but was discharged after contracting hepatitis. At university he met Kristina Hensley, his future wife; they married in 1968.[1]

Despite mild dyslexia, Ford developed a serious interest in literature. He has stated in interviews that his dyslexia may have helped him as a reader, as it forced him to read books slowly and thoughtfully.[4]

Ford briefly attended law school but quit and participated with the creative writing program at the University of California, Irvine, to pursue a Master of Fine Arts degree, which he received in 1970. Ford chose this course simply because "they admitted me. I remember getting the application for Iowa, and thinking they'd never have let me in. I'm sure I was right about that, too. But, typical of me, I didn't know who was teaching at Irvine. I didn't know it was important to know such things. I wasn't the most curious of young men, even though I give myself credit for not letting that deter me." Actually, Oakley Hall and E. L. Doctorow were teaching there, and Ford has acknowledged that they influenced him. In 1971, he was selected for a three-year appointment in the University of Michigan Society of Fellows.[6]

Early career

Ford published his first novel, A Piece of My Heart,[7] the story of two unlikely drifters whose paths cross on an island in the Mississippi River, during 1976, and followed it with The Ultimate Good Luck during 1981. During the interim he briefly taught at Williams College and Princeton University.[1] Despite good notices the books sold little, and Ford retired from fiction writing to become a writer for the New York magazine Inside Sports. "I realized," Ford said, "there was probably a wide gulf between what I could do and what would succeed with readers. I felt that I'd had a chance to write two novels, and neither of them had really created much stir, so maybe I should find real employment, and earn my keep."

During 1982, the magazine was terminated, and when Sports Illustrated did not hire Ford, he resumed writing fiction, composing The Sportswriter,[8] a novel about a failed novelist turned sportswriter who undergoes an emotional crisis after the death of his son. The novel became Ford's first well-known publication, named one of Time magazine's five best books of 1986 and a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction. Ford followed the success immediately with Rock Springs (1987),[9] a story collection mostly set in Montana, includes some of his most popular stories. Reviewers and literary critics associated the stories in Rock Springs with the aesthetic style known as "dirty realism". This term referred to a group of authors during the 1970s and 1980s that included Raymond Carver and Tobias Wolff—- two writers with whom Ford was well acquainted—- along with Ann Beattie, Frederick Barthelme, Larry Brown, and Jayne Anne Phillips, among others.[10] Those applying this label refer to Carver's lower-middle-class subjects or the protagonists Ford portrays in Rock Springs. However, many of the characters of the novels about Frank Bascombe (The Sportswriter, Independence Day, The Lay of the Land, and Let Me Be Frank With You), notably the protagonist himself, enjoy degrees of material affluence and cultural capital not normally associated with dirty realism.

Mid-career and acclaim

His 1990 novel Wildlife, a story of a Montana golf professional turned firefighter, met with mixed reviews and middling sales, but by the end of the 1990s Ford was well known. He was increasingly sought after as an editor and contributor to various projects. Ford edited the 1990 Best American Short Stories, the 1992 Granta Book of the American Short Story, the Fall 1996 "fiction issue" of Ploughshares,[11] and the 1998 Granta Book of the American Long Story. In the latter volume's "Introduction," Ford stipulated that he preferred the designation "long story" instead of term "novella." For the publishing project Library of America, Ford edited a two-volume edition of the selected works of the Mississippi writer Eudora Welty, which was published during 1998.

During 1995, Ford published the novel Independence Day, a sequel to The Sportswriter, featuring the continued story of its protagonist, Frank Bascombe. Reviews were positive, and the novel became the first to win both the PEN/Faulkner Award[12] and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.[13] During the same year, Ford was chosen as winner of the Rea Award for the Short Story, for outstanding achievement for that genre.[14] He ended the 1990s with a well-received collection of short stories, Women With Men, published during 1997. The Paris Review termed him a "master" of the short story genre.[15]

Later life and writings

Ford lived for many years in New Orleans in the French Quarter, on lower Bourbon Street, and then in the Garden District of the same city, where his wife, Kristina, was the executive director of the city planning commission. He now lives in Maine in East Boothbay.[16] During the intervening years, Ford lived in other locations, usually in the United States, as he pursued a peripatetic teaching career.

He obtained a teaching appointment at Bowdoin College during 2005 but kept the job for only one semester.[17] During 2008 Ford was an adjunct professor of the Oscar Wilde Centre with the School of English at Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland, teaching in the Masters programme in creative writing.[18] Starting December 29, 2010, Ford assumed the job of senior fiction professor at the University of Mississippi during the autumn of 2011, replacing Barry Hannah, who died during March 2010. During the autumn of 2012, he became the Emmanuel Roman and Barrie Sardoff Roman Professor of the Humanities and Professor of Writing at the Columbia University School of the Arts.[19]

As the new century commenced, he published another story collection, A Multitude of Sins (2002), followed by the novels The Lay Of The Land, the third Bascombe novel published during 2006, and Canada, published during May 2012.[20] According to Ford, The Lay Of The Land completed his series of Bascombe novels, but Canada was a stand-alone novel. However, during April 2013, Ford read from a new Frank Bascombe story without revealing to the audience whether it was part of a longer work.[21] By 2014, it was confirmed that the story was to appear in the book Let Me Be Frank With You, published during November of that year.[22] The latter is a work consisting of four interconnected novellas (or "long stories": I'm Here, Everything Could Be Worse, The New Normal and Deaths of Others), all narrated by Frank Bascombe.[23] Let Me Be Frank With You was a finalist for the 2015 Pulitzer Prize in Fiction. It did not win the prize, but the selection committee praised the book for its "unflinching series of narratives, set in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, insightfully portraying a society in decline."[24]

Also, as he did in the preceding decade, Ford continued to assist with various editing projects. During 2007, he edited the New Granta Book of the American Short Story, and in 2011 he edited Blue Collar, White Collar, No Collar: Stories of Work. During May 2017, Ford published a memoir, Between Them: Remembering My Parents.[25]

In 2018, Wildlife was adapted into a film of the same name by director Paul Dano and screenwriter Zoe Kazan. It was released to widespread critical acclaim.

Critical opinion

Ford's writing demonstrates "a meticulous concern for the nuances of language ... [and] the rhythms of phrases and sentences". Ford has described his sense of language as "a source of pleasure in itself—- all of its corporeal qualities, its syncopations, moods, sounds, the way things look on the page". Besides this "devotion to language" is what he terms "the fabric of affection that holds people close enough together to survive."[26]

Comparisons have been drawn between Ford's work and the writings of John Updike, William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway and Walker Percy. Ford resists such comparisons, commenting, "You can't write ... on the strength of influence. You can only write a good story or a good novel by yourself".[27]

Ford's works of fiction "dramatize the breakdown of such cultural institutions as marriage, family, and community," and his "marginalized protagonists often typify the rootlessness and nameless longing ... pervasive in a highly mobile, present-oriented society in which individuals, having lost a sense of the past, relentlessly pursue their own elusive identities in the here and now."[28] Ford "looks to art, rather than religion, to provide consolation and redemption in a chaotic time."[29]

Personal life

Ford once sent Alice Hoffman a copy of one of her books with bullet holes in it after she angered him by unfavorably reviewing The Sportswriter.[30]

Ford once spat on Colson Whitehead after a negative review of A Multitude of Sins, resulting in speculation that the incident may have been racially motivated rather than a matter of critical differences.[31]

Awards and honors

- 1995 Rea Award for the Short Story, for outstanding achievement in that genre[14]

- 1996 PEN/Faulkner Award, for Independence Day[12]

- 1996 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, for Independence Day[13]

- 2001 PEN/Malamud Award, for excellence in short fiction

- 2005 St. Louis Literary Award from the Saint Louis University Library Associates[32][33]

- 2008 Kenyon Review Award for Literary Achievement[34]

- 2013 Prix Femina étranger, for Canada

- 2013 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction, for Canada[35]

- 2015 Fitzgerald Award for Achievement in American Literature part of the F. Scott Fitzgerald Literary Festival

- 2015 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, finalist, for Let Me Be Frank with You [24]

- 2016 Princess of Asturias Award in Literature[36]

- 2018 Park Kyong-ni Prize

- 2019 Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction[37]

Bibliography

Novels

- A Piece of My Heart (1976)

- The Ultimate Good Luck (1981)

- The Sportswriter (1986)

- Wildlife (1990)

- Independence Day (1995)

- The Lay of the Land (2006)

- Canada (2012)

- Be Mine (TBC)

Story collections

Memoir

- Between Them: Remembering My Parents (2017)

Screenplays

- Bright Angel (1990)

As contributor or editor

- The Granta Book of the American Short Story (1992)

- The Granta Book of the American Long Story (1999)

- The Essential Tales of Chekhov (1999)

- Foreword to Alec Soth, NIAGARA (Göttingen, Germany: Steidl, 2006)

- The New Granta Book of the American Short Story (2007)

- Blue Collar, White Collar, No Collar: Stories of Work (2011)

- Foreword to Maude Schuyler Clay, Mississippi History (Göttingen, Germany: Steidl, 2015)

References

- Guagliardo 2001, p.xiii.

- Laura Barton (2003-02-08). "Guardian profile". Guardian. London. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- Richard Ford (2013-10-19). "A Boy Who Played with Trains". New York Times. New York. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- "Ford on His Dyslexia, in Conversation with the Washington Post;". Washingtonpost.com. 2006-12-14. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- "Alumni Fellows | Society of Fellows". Societyoffellows.umich.edu. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- 1944-, Ford, Richard (1985-01-01). A Piece of My Heart. Vintage. ISBN 9780394729145. OCLC 924573478.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Ford, Richard (1996-01-01). The Sportswriter. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780679454519. OCLC 35049877.

- Ford, Richard. Rock Springs : Stories. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 9780871131591. OCLC 829387991.

- "Granta interview with Tim Adams". Granta.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-12. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- "Fall 1996 - Ploughshares". www.pshares.org.

- "PEN/Faulkner Foundation list of winners". Penfaulkner.org. Archived from the original on 2008-04-21. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- "Pulitzer Prize citation". Pulitzer.org. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- "Rea Award citation". Reaaward.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- Lyons, Bonnie (1996-01-01). "Richard Ford, The Art of Fiction No. 147". Paris Review (140). ISSN 0031-2037. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- Mehegan, David (2006-12-04). "Boston Globe profile". Boston.com. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- Story posted October 13, 2004 (2004-10-13). "News of Bowdoin College appointment". Bowdoin.edu. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- owc@tcd.ie (2010-12-22). "Oscar Wilde Centre: Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin, Ireland". Tcd.ie. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- "Richard Ford, Pulitzer Prize Winner, Joins Columbia Faculty | Columbia University School of the Arts". Arts.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 2013-12-12. Retrieved 2014-01-10.

- "Canada (novel)". www.harpercollins.com.

- Liu, Lowen (2013-04-30). "Richard Ford's New Frank Bascombe Story Shows the Damage Done by Hurricane Sandy". Slate.com. Retrieved 2014-01-10.

- "Frank and me: Richard Ford on his Bascombe novels". Financial Times. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- Richard Ford, Lyceum Agency, 2014

- "The 2015 Pulitzer Prize Finalist in Fiction", The Pulitzer Prizes.

- "For Richard Ford, Memoir Is A Chance To 'Tell The Unthinkable'". NPR.org.

- Guagliardo 2001, p.vii.

- Guagliardo 2001, p. xi.

- Guagliardo 2000, p. xiv.

- Guagliardo 2000, p. xvi.

- "Richard Ford and Alice Hoffman 30 years later". EW.com. 23 March 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- "Richard Ford, pissed about negative review, spits on Colson Whitehead". Mar 15, 2004. Retrieved Sep 26, 2019.

- "Saint Louis Literary Award - Saint Louis University". www.slu.edu.

- Saint Louis University Library Associates. "Richard Ford to Receive 2005 Saint Louis Literary Award". Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- "Kenyon Review for Literary Achievement". KenyonReview.org.

- Italie, Hillel (June 30, 2013). "Ford, Egan Win Literary Medals". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- "Richard Ford wins Princess of Asturias Award for Literature". euronews. 15 June 2016.

- Ray Routhier (May 16, 2019). "Maine author Richard Ford wins lifetime achievement award from Library of Congress". Portland Press Herald. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- Michael Schaub. "Frankly, Bascombe's Return Has Some Problems", 2014-11-06. Retrieved 2015-01-06.

- Routhier, Ray (May 16, 2019). "Maine author Richard Ford wins lifetime achievement award from Library of Congress". Retrieved Sep 26, 2019.

Works cited

- Elinor Walker, Richard Ford (New York, NY; Twayne Publishers, 2000) ISBN 0805716793

- Huey Guagliardo, Perspectives on Richard Ford: Redeemed by Affection (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2000) ISBN 978-1-57806-234-8

- Huey Guagliardo, ed., Conversations with Richard Ford (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2001) ISBN 978-1-57806-406-9

- Brian Duffy, Morality, Identity and Narrative in the Fiction of Richard Ford, (New York, NY; Amsterdam; Rodopi, 2008) ISBN 978-904202-409-0

- Joseph M. Armengol, Richard Ford and the Fiction of Masculinities (New York, NY: Peter Lang, 2010) ISBN 978-143311-086-3

- Ian McGuire, Richard Ford and the Ends of Realism (Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press, 2015) ISBN 978-1-60938-343-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Richard Ford. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Richard Ford |

- Work

- "Nobody's Everyman", Bookforum (Apr/May 2009)

- Leaving for Kenosha, The New Yorker (2008)

- How Was it to be Dead?, The New Yorker (2006)

- Profiles

- Bibliography, University of Mississippi

- Profile, Ploughshares

- Richard Ford on IMDb

- Overview of Ford's recent career, and critique of short stories in The Walrus magazine

- Interviews

- Interview on the 7th Avenue Project radio show Richard Ford discusses his Frank Bascombe novels, his approach to fiction and his life.

- Bonnie Lyons (Fall 1996). "Richard Ford, The Art of Fiction No. 147". Paris Review. Fall 1996 (140).

- "Armistead Maupin: Brisbane Writers' Festival – RN Book Show – 23 January 2008". Abc.net.au. 2008-01-23. Retrieved 2011-08-19. – Transcript of interview with Ramona Koval, The Book Show, ABC Radio National 31 December 2007

- Interview for public radio in Maine (2006), Maine Humanities Council

- Interview (1996), Salon.com

- Interview on Writer's Voice (2006) with radio host, Francesca Rheannon

- Interview (2002), IdentityTheory.com

- Interview (2006), The New Yorker

- Interview (2006), Nerve.com

- Interview, book reading, and discussion video streams and MP3 download (2006), University of Pennsylvania

- Interview February 2007; Pulitzer Prize-winning author talks with Robert Birnbaum about his latest Frank Bascombe novel, The Lay of the Land

- Richard Ford: Shooting for the stars. Video interview by Louisiana Channel 2012.

- Interview (2016), The Ringer (website)

- Archival collections

- Guide to The Ultimate Good Luck Galley Proofs. Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California.

- Richard Ford Collection owned by the University of Mississippi Department of Archives and Special Collections.