Greenwood, Mississippi

Greenwood is a city in and the county seat of Leflore County, Mississippi,[3] located at the eastern edge of the Mississippi Delta, approximately 96 miles north of the state capital, Jackson, Mississippi, and 130 miles south of the riverport of Memphis, Tennessee. It was a center of cotton planter culture in the 19th century.

Greenwood, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

City | |

| |

| Nickname(s): Cotton Capital of the World | |

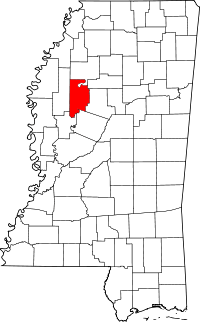

Location of Greenwood, Mississippi | |

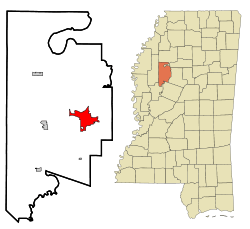

Greenwood, Mississippi Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 33°31′7″N 90°11′2″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Leflore |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Carolyn McAdams (I) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 12.69 sq mi (32.87 km2) |

| • Land | 12.34 sq mi (31.95 km2) |

| • Water | 0.36 sq mi (0.92 km2) |

| Elevation | 131 ft (40 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 15,205 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 13,561 |

| • Density | 1,099.39/sq mi (424.48/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 38930, 38935 |

| Area code(s) | 662 |

| FIPS code | 28-29340 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0670714 |

| Website | www |

The population was 15,205 at the 2010 census. It is the principal city of the Greenwood Micropolitan Statistical Area. Greenwood developed at the confluence of the Tallahatchie and the Yalobusha rivers, which form the Yazoo River. Throughout the 1960s, Greenwood was the site of major protests and conflicts as African Americans worked to achieve racial integration, voter registration and access during the civil rights movement.

History

Native Americans

The flood plain of the Mississippi River has long been an area rich in vegetation and wildlife, fed by the Mississippi and its numerous tributaries. Long before Europeans migrated to America, the Choctaw and Chickasaw Indian nations settled in the Delta's bottomlands and throughout what is now central Mississippi. They were descended from indigenous peoples who had lived in the area for thousands of years. The Mississippian culture had built earthwork mounds in this area and throughout the Mississippi Valley, beginning about 950 CE. Their culture thrived for hundreds of years.

In the nineteenth century, the Five Civilized Tribes in the Southeast suffered increasing encroachment on their territory by European-American settlers from the United States. Under pressure from the United States government, in 1830 the Choctaw principal chief Greenwood LeFlore and other Choctaw leaders signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, ceding most of their remaining land to the United States in exchange for land in Indian Territory, what is now southeastern Oklahoma. The government opened the land for sale and settlement by European Americans. LeFlore came to regret his decision on land cession, saying in 1843 that he was "sorry to say that the benefits realized from [the treaty] by my people were by no means equal to what I had a right to expect, nor to what they were justly entitled."[4]

European settlement

The first Euro-American settlement on the banks of the Yazoo River was a trading post founded in 1834 by Colonel Dr. John J. Dilliard[5]:7 and known as Dilliard's Landing. The settlement had competition from Greenwood Leflore's rival landing called Point Leflore, located three miles up the Yazoo River. The rivalry ended when Captain James Dilliard donated parcels in exchange for a commitment from the townsmen to maintain an all-weather turnpike to the hill section to the east, along with a stagecoach road to the more established settlements to the northwest.[6]

The settlement was incorporated as "Greenwood" in 1844, named after Chief Greenwood LeFlore. The success of the city, founded during a strong international demand for cotton, was based on its strategic location in the heart of the Delta: on the easternmost point of the alluvial plain, and astride the Tallahatchie and Yazoo rivers. The city served as a shipping point for cotton to major markets in New Orleans, Vicksburg, Mississippi, Memphis, Tennessee, and St. Louis, Missouri.

Thousands of slaves were transported as laborers to Mississippi from the Upper South through the domestic slave trade, in a forced migration that moved more than one million slaves in total to the Deep South to satisfy the demand for labor. Cotton cultivation was developed in these new territories of the Deep South. Greenwood continued to prosper, based on slave labor on the cotton plantations and in shipping, until the latter part of the American Civil War.

Later 19th century

With the abolition of slavery after the end of the Civil War in 1865, the labor market was changed to one of free labor. Away from the riverfronts, the state was 90 per cent undeveloped frontier. Many freedmen withdrew from working for others. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, many blacks managed to clear and buy their own farms in the bottomlands behind the rivers.[7] With the disruption caused by war and with changes to labor, cotton production initially declined, harming Greenwood's previously thriving economy.

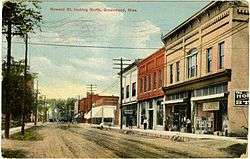

The construction of railroads through the area in the 1880s revitalized the city;[5]:8 two rail lines ran to downtown Greenwood close to the Yazoo River, and shortened transportation to markets. Greenwood again emerged as a prime shipping point for cotton. Downtown's Front Street, bordering the Yazoo, was dominated by cotton factors and related businesses, earning that section the name 'Cotton Row'.

20th century

The city continued to prosper well into the 1940s. Cotton production suffered in Mississippi during the infestation of the boll weevil in the early 20th century; however, for many years the bridge over the Yazoo displayed the sign "World's Largest Inland Long Staple Cotton Market".

Cotton cultivation and processing became largely mechanized in the first half of the 20th century, displacing thousands of sharecroppers and tenant farmers. Since the late 20th century, some Mississippi farmers have begun to replace cotton with corn and soybeans as commodity crops; with the textile manufacturing industry having shifted overseas, farmers can gain stronger prices for the newer crops, used mostly as animal feed.[8]

Greenwood's Grand Boulevard was once named one of America's 10 most beautiful streets by the U.S. Chambers of Commerce and the Garden Clubs of America. Sally Humphreys Gwin, a charter member of the Greenwood Garden Club, planted the 1,000 oak trees that line Grand Boulevard. In 1950, Gwin received a citation from the National Congress of the Daughters of the American Revolution in recognition of her work in the conservation of trees.[9][10]

Civil rights era

In 1955, following the US Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education that segregated public education was unconstitutional, Robert B. Patterson in Greenwood founded the White Citizens' Council to fight against racial integration. Chapters were established across the state.[11]

From 1962 to 1965, Greenwood was a center of protests and voter registration struggles during the Civil Rights Movement. The SNCC, COFO, and the MFDP were all active in the city. During this period, hundreds of African Americans were arrested in nonviolent protests; civil rights activists were subjected to repeated violence by police and whites. In addition, whites used economic retaliation against African Americans who attempted to register to vote: they fired them from jobs, evicted them from rental housing, and cut off federal commodity subsidies in poor communities.[12]

The city police set their police dogs on protesters, with white counter-protesters yelling "Sic 'em" from the sidewalk.[13]

The Catholic peace organization Pax Christi, which had a chapter in the city, organized an economic boycott of businesses that discriminated against blacks, thereby supporting the civil rights movement. Pax Christi's ultimately successful efforts were encouraged by native Mississippian Joseph Bernard Brunini, the Bishop of Jackson.[14]

Major gains were achieved by the movement with Congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965. However, much remained to be accomplished in terms of enacting these laws. White resistance to change continued. In June 1966, James Meredith, the first African American to attend the University of Mississippi, announced that to protest racism, he was going to walk from Memphis to Jackson, a distance of more than 200 miles, in a March Against Fear. He invited only men to walk with him, in a journey he wanted to be independent of the movement organizations. After Meredith was shot and hospitalized for injuries two days into his walk,[15] a number of high-profile civil rights leaders of major organizations, including Stokely Carmichael of SNCC, Martin Luther King of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Floyd McKissick and Roger Wilkins of the NAACP, vowed to continue the march. They encouraged others to join them.

Their goals differed, and organizing the logistics of food and shelter for larger groups were more difficult. The state committed to protect the marchers if they obeyed the law. Some groups expanded their goals in the march to achieve community organizing and voter registration in the Delta communities they encountered. National leaders tended to come and go, checking in on the march in the midst of other responsibilities; some marchers also walked for short periods, while others stayed through most of the journey. With high-spirited gatherings and song, they recruited marchers from local residents, for at least part of the journey. Many local whites jeered and threatened the marchers, driving near them and waving Confederate flags.

When the group reached Greenwood on June 17, Carmichael was arrested but released after a few hours. Later, in Greenwood's Broad Street Park, Carmichael gave his Black Power speech, which became well known, stating:

This is the twenty-seventh time I have been arrested—and I ain't going to jail no more! The only way we gonna stop them white men from whuppin' us is to take over. We been sayin' "freedom" for six years and we ain't got nothin'. What we gonna start saying now is Black Power![16]

The speech marked a turning point in the civil rights movement; many younger members took up Carmichael's slogan, and used it to support the use of violence to defend their freedom.[17] This seemed to catalyze the fragmentation of the civil rights movement in the mid 1960s,[18] but the process was already under way. On this occasion, the marchers persisted, growing in number as they neared the capital, and totaled more than 15,000 when they entered Jackson.

21st century

In 2006, the first female and first African-American mayor, Sheriel F. Perkins, was elected.[19]

Geography

Greenwood is located at 33°31′7″N 90°11′2″W (33.518719, -90.183883).[20] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 9.5 square miles (25 km2), of which 9.2 square miles (24 km2) is land and 0.3 square miles (0.78 km2) is water.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 308 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,055 | 242.5% | |

| 1900 | 3,026 | 186.8% | |

| 1910 | 5,836 | 92.9% | |

| 1920 | 7,793 | 33.5% | |

| 1930 | 11,123 | 42.7% | |

| 1940 | 14,767 | 32.8% | |

| 1950 | 18,061 | 22.3% | |

| 1960 | 20,436 | 13.1% | |

| 1970 | 22,400 | 9.6% | |

| 1980 | 20,115 | −10.2% | |

| 1990 | 18,906 | −6.0% | |

| 2000 | 18,425 | −2.5% | |

| 2010 | 15,205 | −17.5% | |

| Est. 2019 | 13,561 | [2] | −10.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[21] | |||

2010 census

At the 2010 census,[22] there were 15,205 people and 6,022 households in the city. The population density was 1,237.7 per square mile (771.6/km2). There were 6,759 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 30.4% White, 67.0% Black, 0.1% Native American, 0.9% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander, <0.1% from other races, and 0.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.1% of the population.

Among the 6,022 households, 28.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 29.8% were married couples living together, 29.0% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 36.6% were non-families. 32.5% of all households were made up of individuals living alone and 10.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.48 and the average family size was 3.16.

Mississippi Blues Trail markers

Radio station WGRM on Howard Street was the location of B.B. King's first live broadcast in 1940. On Sunday nights, King performed live gospel music as part of a quartet.[23] In memory of this event, the Mississippi Blues Trail has placed its third historic marker in this town at the site of the former radio station.[24][25] Another Mississippi Blues Trail marker is placed near the grave of the blues singer Robert Johnson.[26] A third Blues Trail marker notes the Elks Lodge in the city, which was an important black organization.[27] A fourth Blues Trail marker was dedicated to Hubert Sumlin that is located along the Yazoo River on River Road. [28]

Gallery of Mississippi Blues Trail markers in Greenwood

Elks Hart Lodge No. 640 Blues Trail marker

Elks Hart Lodge No. 640 Blues Trail marker Baptist Town Blues Trail marker

Baptist Town Blues Trail marker Robert Johnson Blues trail marker located north of Greenwood on Money Road

Robert Johnson Blues trail marker located north of Greenwood on Money Road WGRM Radio Studio Blues Trail marker

WGRM Radio Studio Blues Trail marker Hubert Sumlin Blues Trail marker

Hubert Sumlin Blues Trail marker

Government and infrastructure

Local government

Greenwood is governed under a city council form of government, composed of council members elected from seven single-member wards and headed by a mayor, who is elected at-large.

State and federal representation

The United States Postal Service operates two post offices in Greenwood: Greenwood and Leflore.[29][30]

Media and publishing

Newspapers, magazines and journals

Television

- WABG-TV - ABC/Fox affiliate

- WMAO-TV - PBS affiliate

Transportation

Railroads

Greenwood is served by two major rail lines. Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides service to Greenwood, connecting New Orleans to Chicago from Greenwood station.

Air transportation

Greenwood is served by Greenwood–Leflore Airport (GWO) to the east, and is located midway between Jackson, Mississippi, and Memphis, Tennessee. It is about halfway between Dallas, Texas, and Atlanta, Georgia.

Highways

- U.S. Route 82 runs through Greenwood on its way from Georgia's Atlantic coast (Brunswick, Georgia) to the White Sands of New Mexico (east of Las Cruces).

- U.S. Route 49 passes through Greenwood as it stretches between Piggott, Arkansas, south to Gulfport.

- Other Greenwood highways include Mississippi Highway 7.

Education

Greenwood Public School District operates public schools. Greenwood High School is the only public high school in Greenwood. As of 2014, the student body is 99% black.

Leflore County School District operates schools outside the Greenwood city area, including Amanda Elzy High School.

On July 1, 2019 the districts will consolidate into Greenwood Leflore Consolidated School District (GLCSD).[31]

Pillow Academy, a private school, is located in unincorporated Leflore County, near Greenwood.

Delta Streets Academy, a newly founded private school located in downtown Greenwood, has an enrollment of nearly 50 students. It has continued to increase enrollment.

St. Francis Catholic School, run by the Catholic Church, provides classes from kindergarten through sixth grade.

In addition, North New Summit School provides educational services for special-needs and at-risk children from kindergarten through high school.

In popular culture

Nightmare in Badham County (1976), Ode to Billy Joe (1976), and The Help (2011) were filmed in Greenwood.[32] The 1991 movie Mississippi Masala was also set and filmed in Greenwood.[33]

Notable people

- Valerie Brisco-Hooks, Olympic athlete[34]

- Nora Jean Bruso, blues singer and songwriter[35]

- Fred Carl, Jr., founder/CEO of Viking Range Corp.[36]

- Louis Coleman, Major League Baseball pitcher[37]

- Byron De La Beckwith, white supremacist, assassin of civil rights leader Medgar Evers[38]

- Carlos Emmons, professional football player[39]

- Betty Everett, R&B vocalist and pianist[40]

- James L. Flanagan, electrical engineer and speech scientist

- Alphonso Ford, professional basketball player[41]

- Webb Franklin, United States congressman[42]

- Morgan Freeman, actor[36]

- Jim Gallagher, Jr., professional golfer[43]

- Bobbie Gentry, singer/songwriter[44]

- Sherrod Gideon, professional football player[45]

- Gerald Glass, professional basketball player

- Guitar Slim, blues musician[46]

- Lusia Harris, basketball player[47]

- Endesha Ida Mae Holland, American scholar, playwright, and civil rights activist

- Kent Hull, professional football player[48]

- Tom Hunley, ex-slave and the inspiration for the character "Hambone" in J. P. Alley's syndicated cartoon feature, Hambone's Meditations[49]

- Robert Johnson, blues musician[36]

- Jermaine Jones, soccer player for the New England Revolution and United States national team[50]

- Cleo Lemon, Toronto Argonauts quarterback[51]

- Walter "Furry" Lewis, blues musician[52]

- Bernie Machen, president of the University of Florida[53]

- Paul Maholm, baseball pitcher[54]

- Matt Miller, baseball pitcher[55]

- Mulgrew Miller, jazz pianist[56]

- Carrie Nye, actress[57]

- W. Allen Pepper Jr., US federal judge[58]

- Fenton Robinson, blues singer/guitarist[59]

- Richard Rubin, writer and journalist[60]

- Laverne Smith, NFL player

- Tonea Stewart, actress[61]

- Hubert Sumlin, blues guitarist[62]

- Donna Tartt, novelist[63]

- James K. Vardaman, Mississippi governor and senator

- Charlie Wells, hardboiled mystery writer, author of Let the Night Fall (1953) and The Last Kill (1955)

- Willye B. White, Olympic athlete[64]

See also

- Confederacy of Silence: A True Tale of the New Old South, by Richard Rubin

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- Greg O'Brien (2008). Pre-removal Choctaw History: Exploring New Paths. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-8061-3916-6. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- Donny Whitehead; Mary Carol Miller (September 14, 2009). Greenwood. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-6786-0. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- Smith, Frank E. (1954). The Yazoo River. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. pp. 57-58. ISBN 0-87805-355-7

- John C. Willis, Forgotten Time: The Yazoo-Mississippi Delta after the Civil War. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2000

- Krauss, Clifford. "Mississippi Farmers Trade Cotton Plantings for Corn", The New York Times, May 5, 2009

- "NewspaperArchive® - Genealogy & Family History Records". Newspaperarchive.com. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- Kirkpatrick, Mario Carter. Mississippi Off the Beaten Path, GPP Travel, 2007.

- "White Citizens' Councils aimed to maintain 'Southern way of life'". Jackson Sun. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- Mississippi Voter Registration — Greenwood, crmvet.org; accessed June 29, 2018.

- Hendrickson, Paul (2003). Sons of Mississippi. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40461-9.

- Michael V. Namorato (1998). The Catholic Church in Mississippi: 1911-1984; a History. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-313-30719-5. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- "On this day June 6, 1966: Black civil rights activist shot". BBC. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- Matthew C. Whitaker Ph.D. (March 1, 2011). Icons of Black America: Breaking Barriers and Crossing Boundaries [Three Volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-313-37643-6. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- Richard T. Schaefer (March 20, 2008). Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society. SAGE Publications. p. 246. ISBN 978-1-4129-2694-2. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- Williams, Horace Randall and Ben Beard (2009). This Day in Civil Rights History. NewSouth Books. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-58835-241-5. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- Fausset, Richard (7 June 2009). "In Mississippi, race plays out in mayoral election". Retrieved 28 July 2018 – via LA Times.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Greenwood Mississippi". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- Cloues, Kacey. "Great Southern Getaways - Mississippi" (PDF). www.atlantamagazine.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-06-25. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- "Historical marker placed on Mississippi Blues Trail". Associated Press. January 25, 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-09.

- "Film crew chronicles blues markers" (PDF). The Greenwood Commonwealth. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- Widen, Larry. "JS Online: Blues trail". www.jsonline.com. Archived from the original on 2007-12-15. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- "Mississippi Blues Commission - Blues Trail". www.msbluestrail.org. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- "Mississippi Blues Commission - Blues Trail". www.msbluestrail.org. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- "Post Office Location - GREENWOOD Archived 2012-06-14 at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on August 12, 2010.

- "Post Office Location - LEFLORE Archived 2012-06-14 at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on August 12, 2010.

- "School District Consolidation in Mississippi Archived 2017-07-02 at the Wayback Machine." Mississippi Professional Educators. December 2016. Retrieved on July 2, 2017. Page 2 (PDF p. 3/6).

- Barth, Jack (1991). Roadside Hollywood: The Movie Lover's State-By-State Guide to Film Locations, Celebrity Hangouts, Celluloid Tourist Attractions, and More. Contemporary Books, p. 169. ISBN 9780809243266.

- "Mississippi Masala (1991) Filming & Production". IMDb. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- Mike Celizic (February 11, 1985). "Stardom Comes too Slowly for Speedster". The Record. p. s09.

- Richard Skelly. "Nora Jean Bruso | Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- "Carl Small Town Center Continues Making a Difference in the Delta". US Fed News. December 4, 2013.

- "Louis Coleman Stats". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- "A Little Abnormal: The Life of Byron De La Beckwith". Time. July 5, 1963. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- "Football Signings in the Mid-South". The Commercial Appeal. February 7, 1991. p. D5.

- "Betty Everett, 61, of 'The Shoop Shoop Song'". New York Times. August 23, 2001. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- Bryan Crawford (October 29, 2009). "Ford left huge legacy in Euroleague basketball". Greenwood Commonwealth.

- "Franklin, William Webster, (1941 - )". U.S. Congress. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- Bill Burrus (July 19, 2012). "A hectic week for golfing Gallaghers". Greenwood Commonwealth.

- John Howard (10 October 2001). Men Like That: A Southern Queer History. University of Chicago Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-226-35470-5.

- "Sherrod Gideon". TheProFootballArchives. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- Scott Stanton (1 September 2003). The Tombstone Tourist: Musicians. Gallery Books. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-7434-6330-0.

- David Kenneth Wiggins (2010). Sport in America: From Colonial Leisure to Celebrity Figures and Globalization. Human Kinetics. p. 370. ISBN 978-1-4504-0912-4.

- Sal Maiorana (January 2005). Memorable Stories of Buffalo Bills Football. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-58261-963-7.

- "Mississippi Slave Narratives from the WPA Records". MSGenWeb. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- Filip Bondy (27 April 2010). Chasing the Game: America and the Quest for the World Cup. Da Capo Press, Incorporated. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-306-81905-6.

- "Cleo Lemon". Nfl.com. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- Paul Oliver (27 September 1984). Songsters and Saints: Vocal Traditions on Race Records. Cambridge University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-521-26942-1.

- "The President". University of Florida. Archived from the original on January 19, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- "Paul Maholm Stats". Mlb.com. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- "Matt Miller Stats". Mlb.com. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- Bob Doerschuk (2001). 88: The Giants of Jazz Piano. Backbeat Books. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-87930-656-4.

- Max Apple (1976). Mom, the Flag, and Apple Pie: Great American Writers on Great American Things. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-385-11459-2.

- The Martindale-Hubbell Law Directory. 10. LexisNexis. 1996. p. 1135.

- Nigel Williamson; Robert Plant (2 April 2007). The rough guide to the blues. Rough Guides. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-84353-519-5.

- Richard Rubin (15 June 2010). Confederacy of Silence: A True Tale of the New Old South. Simon and Schuster. p. 2. ISBN 1-4516-0265-0.

- Bob McCann (2010). Encyclopedia of African American Actresses in Film and Television. McFarland. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-7864-5804-2.

- Jas Obrecht (2000). Rollin' and Tumblin': The Postwar Blues Guitarists. Miller Freeman Books. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-87930-613-7.

- Tracy Hargreaves (1 September 2001). Donna Tartt's The Secret History: A Reader's Guide. Continuum. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8264-5320-4.

- Martha Ward Plowden (January 1996). Olympic Black Women. Pelican Publishing. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-4556-0994-9.