Nitrogen trifluoride

Nitrogen trifluoride is the inorganic compound with the formula NF3. This nitrogen-fluorine compound is a colorless, nonflammable gas with a slightly musty odor. It finds increasing use as an etchant in microelectronics. Nitrogen trifluoride is an extremely strong greenhouse gas.

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Nitrogen trifluoride | |

| Other names

Nitrogen fluoride Trifluoramine Trifluorammonia | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.097 |

| EC Number |

|

| 1551 | |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 2451 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| NF3 | |

| Molar mass | 71.00 g/mol |

| Appearance | colorless gas |

| Odor | moldy |

| Density | 3.003 kg/m3 (1 atm, 15 °C) 1.885 g/cm3 (liquid at b.p.) |

| Melting point | −207.15 °C (−340.87 °F; 66.00 K) |

| Boiling point | −129.06 °C (−200.31 °F; 144.09 K) |

| 0.021 g/100 mL | |

| Vapor pressure | 44.0 atm[1](−38.5 °F or −39.2 °C or 234.0 K)[lower-alpha 1] |

Refractive index (nD) |

1.0004 |

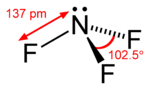

| Structure | |

| trigonal pyramidal | |

| 0.234 D | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C) |

53.26 J/(mol·K) |

Std molar entropy (S |

260.3 J/(mol·K) |

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−31.4 kJ/mol[2] −109 kJ/mol[3] |

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG˚) |

−84.4 kJ/mol |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | AirLiquide |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LC50 (median concentration) |

2000 ppm (mouse, 4 h) 9600 ppm (dog, 1 h) 7500 ppm (monkey, 1 h) 6700 ppm (rat, 1 h) 7500 ppm (mouse, 1 h)[4] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 10 ppm (29 mg/m3)[5] |

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 10 ppm (29 mg/m3)[5] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

1000 ppm[5] |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions |

nitrogen trichloride nitrogen tribromide nitrogen triiodide ammonia |

Other cations |

phosphorus trifluoride arsenic trifluoride antimony trifluoride bismuth trifluoride |

Related binary fluoro-azanes |

tetrafluorohydrazine |

Related compounds |

dinitrogen difluoride |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Synthesis and reactivity

Nitrogen trifluoride is a rare example of a binary fluoride that can be prepared directly from the elements only at very uncommon conditions, such as electric discharge.[6] After first attempting the synthesis in 1903, Otto Ruff prepared nitrogen trifluoride by the electrolysis of a molten mixture of ammonium fluoride and hydrogen fluoride.[7] It proved to be far less reactive than the other nitrogen trihalides nitrogen trichloride, nitrogen tribromide and nitrogen triiodide, all of which are explosive. Alone among the nitrogen trihalides it has a negative enthalpy of formation. Today, it is prepared both by direct reaction of ammonia and fluorine and by a variation of Ruff's method.[8] It is supplied in pressurized cylinders.

Reactions

NF3 is slightly soluble in water without undergoing chemical reaction. It is nonbasic with a low dipole moment of 0.2340 D. By contrast, ammonia is basic and highly polar (1.47 D).[9] This difference arises from the fluorine atoms acting as electron withdrawing groups, attracting essentially all of the lone pair electrons on the nitrogen atom. NF3 is a potent yet sluggish oxidizer.

It oxidizes hydrogen chloride to chlorine:

- 2 NF3 + 6 HCl → 6 HF + N2 + 3 Cl2

It converts to tetrafluorohydrazine upon contact with metals, but only at high temperatures:

- 2 NF3 + Cu → N2F4 + CuF2

NF3 reacts with fluorine and antimony pentafluoride to give the tetrafluoroammonium salt:

- NF3 + F2 + SbF5 → NF+

4SbF−

6

Applications

Nitrogen trifluoride is used in the plasma etching of silicon wafers. Today nitrogen trifluoride is predominantly employed in the cleaning of the PECVD chambers in the high-volume production of liquid-crystal displays and silicon-based thin-film solar cells. In these applications NF3 is initially broken down in situ by a plasma. The resulting fluorine atoms are the active cleaning agents that attack the polysilicon, silicon nitride and silicon oxide. Nitrogen trifluoride can be used as well with tungsten silicide, and tungsten produced by CVD. NF3 has been considered as an environmentally preferable substitute for sulfur hexafluoride or perfluorocarbons such as hexafluoroethane.[10] The process utilization of the chemicals applied in plasma processes is typically below 20%. Therefore some of the PFCs and also some of the NF3 always escape into the atmosphere. Modern gas abatement systems can decrease such emissions.

F2 gas (diatomic fluorine) has been introduced as a climate neutral replacement for nitrogen trifluoride in the manufacture of flat-panel displays and thin-film solar cells.[11]

Nitrogen trifluoride is also used in hydrogen fluoride and deuterium fluoride lasers, which are types of chemical lasers. It is preferred to fluorine gas due to its convenient handling properties, reflecting its considerable stability.

It is compatible with steel and Monel, as well as several plastics.

Greenhouse gas

NF

3 is a greenhouse gas, with a global warming potential (GWP) 17,200 times greater than that of CO

2 when compared over a 100-year period.[12][13][14] Its GWP place it second only to SF

6 in the group of Kyoto-recognised greenhouse gases, and NF

3 was included in that grouping with effect from 2013 and the commencement of the second commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol. It has an estimated atmospheric lifetime of 740 years,[12] although other work suggests a slightly shorter lifetime of 550 years (and a corresponding GWP of 16,800).[15]

Although NF

3 has a high GWP, for a long time its radiative forcing in the Earth's atmosphere has been assumed to be small, spuriously presuming that only small quantities are released into the atmosphere. Industrial applications of NF

3 routinely break it down, while in the past previously used regulated compounds such as SF

6 and PFCs were often released. Research has questioned the previous assumptions. High-volume applications such as DRAM computer memory production, the manufacturing of flat panel displays and the large-scale production of thin-film solar cells use NF

3.[15][16]

Since 1992, when less than 100 tons were produced, production has grown to an estimated 4000 tons in 2007 and is projected to increase significantly.[15] World production of NF3 is expected to reach 8000 tons a year by 2010. By far the world's largest producer of NF

3 is the US industrial gas and chemical company Air Products & Chemicals. An estimated 2% of produced NF

3 is released into the atmosphere.[17][18] Robson projected that the maximum atmospheric concentration is less than 0.16 parts per trillion (ppt) by volume, which will provide less than 0.001 Wm−2 of IR forcing.[19]

The mean global tropospheric concentration of NF3 has risen from about 0.02 ppt (parts per trillion, dry air mole fraction) in 1980, to 0.86 ppt in 2011, with a rate of increase of 0.095 ppt yr−1, or about 11% per year, and an interhemispheric gradient that is consistent with emissions occurring overwhelmingly in the Northern Hemisphere, as expected. This rise rate in 2011 corresponds to about 1200 metric tons/y NF3 emissions globally, or about 10% of the NF3 global production estimates. This is a significantly higher percentage than has been estimated by industry, and thus strengthens the case for inventorying NF3 production and for regulating its emissions.[20]

One study co-authored by industry representatives suggests that the contribution of the NF3 emissions to the overall greenhouse gas budget of thin-film Si-solar cell manufacturing is overestimated. Instead, the contribution of the nitrogen trifluoride to the CO2-budget of thin film solar cell production is compensated already within a few months by the CO2 saving potential of the PV technology.[21]

The UNFCCC, within the context of the Kyoto Protocol, decided to include nitrogen trifluoride in the second Kyoto Protocol compliance period, which begins in 2012 and ends in either 2017 or 2020. Following suit, the WBCSD/WRI GHG Protocol is amending all of its standards (corporate, product and Scope 3) to also cover NF3.[22]

Safety

Skin contact with NF

3 is not hazardous, and it is a relatively minor irritant to mucous membranes and eyes. It is a pulmonary irritant with a toxicity considerably lower than nitrogen oxides, and overexposure via inhalation causes the conversion of hemoglobin in blood to methemoglobin, which can lead to the condition methemoglobinemia.[23] The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) specifies that the concentration that is immediately dangerous to life or health (IDLH value) is 1,000 ppm.[24]

Notes

- This vapour pressure is the pressure at its critical temperature – below ordinary room temperature.

References

- Air Products; Physical Properties for Nitrogen Trifluoride

- Sinke, G. C. (1967). "The enthalpy of dissociation of nitrogen trifluoride". J. Phys. Chem. 71 (2): 359–360. doi:10.1021/j100861a022.

- Inorganic Chemistry, p. 462, at Google Books

- "Nitrogen trifluoride". Immediately Dangerous to Life and Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0455". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Lidin, P. A.; Molochko, V. A.; Andreeva, L. L. (1995). Химические свойства неорганических веществ (in Russian). pp. 442–455. ISBN 978-1-56700-041-2.

- Otto Ruff, Joseph Fischer, Fritz Luft (1928). "Das Stickstoff-3-fluorid". Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie. 172 (1): 417–425. doi:10.1002/zaac.19281720132.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Philip B. Henderson, Andrew J. Woytek "Fluorine Compounds, Inorganic, Nitrogen" in Kirk‑Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, 1994, John Wiley & Sons, NY. doi:10.1002/0471238961.1409201808051404.a01 Article Online Posting Date: December 4, 2000

- Klapötke, Thomas M. (2006). "Nitrogen–fluorine compounds". Journal of Fluorine Chemistry. 127: 679–687. doi:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2006.03.001.

- H. Reichardt , A. Frenzel and K. Schober (2001). "Environmentally friendly wafer production: NF

3 remote microwave plasma for chamber cleaning". Microelectronic Engineering. 56 (1–2): 73–76. doi:10.1016/S0167-9317(00)00505-0. - J. Oshinowo; A. Riva; M Pittroff; T. Schwarze; R. Wieland (2009). "Etch performance of Ar/N2/F2 for CVD/ALD chamber clean". Solid State Technology. 52 (2): 20–24.

- "Climate Change 2007: The Physical Sciences Basis" (PDF). IPCC. Retrieved 2008-07-03. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Robson, J. I.; Gohar, L. K.; Hurley, M. D.; Shine, K. P.; Wallington, T. (2006). "Revised IR spectrum, radiative efficiency and global warming potential of nitrogen trifluoride". Geophys. Res. Lett. 33 (10): L10817. Bibcode:2006GeoRL..3310817R. doi:10.1029/2006GL026210.

- Richard Morgan (2008-09-01). "Beyond Carbon: Scientists Worry About Nitrogen's Effects". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2008-09-07. Retrieved 2008-09-07.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Prather, M.J.; Hsu, J. (2008). "NF

3, the greenhouse gas missing from Kyoto". Geophys. Res. Lett. 35 (12): L12810. Bibcode:2008GeoRL..3512810P. doi:10.1029/2008GL034542. - Tsai, W.-T. (2008). "Environmental and health risk analysis of nitrogen trifluoride (NF

3), a toxic and potent greenhouse gas". J. Hazard. Mat. 159 (2–3): 257–63. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.02.023. PMID 18378075. - M. Roosevelt (2008-07-08). "A climate threat from flat TVs, microchips". Los Angeles Times.

- Hoag, Hannah (2008-07-10). "The Missing Greenhouse Gas". Nature Reports Climate Change. Nature News. doi:10.1038/climate.2008.72.

- Robson, Jon. "Nitrogen trifluoride (NF3)". Royal Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-27. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Arnold, Tim; Harth, C. M.; Mühle, J.; Manning, A. J.; Salameh, P. K.; Kim, J.; Ivy, D. J.; Steele, L. P.; Petrenko, V. V.; Severinghaus, J. P.; Baggenstos, D.; Weiss, R. F. (2013-02-05). "Nitrogen trifluoride global emissions estimated from updated atmospheric measurements". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110 (6): 2029–2034. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.2029A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1212346110. PMC 3568375. PMID 23341630.

- Fthenakis, Vasilis; D. O. Clark; M. Moalem; M. P. Chandler; R. G. Ridgeway; F. E. Hulbert; D. B. Cooper; P. J. Maroulis (2010-10-25). "Life-Cycle Nitrogen Trifluoride Emissions from Photovoltaics". Environ. Sci. Technol. American Chemical Society. 44 (22): 8750–7. Bibcode:2010EnST...44.8750F. doi:10.1021/es100401y. PMID 21067246.

- Rivers, Ali (2012-08-15). "Nitrogen trifluoride: the new mandatory Kyoto Protocol greenhouse gas". Ecometrica.com. www.ecometrica.com.

- Malik, Yogender (2008-07-03). "Nitrogen trifluoride – Cleaning up in electronic applications". Gasworld. Archived from the original on 2008-08-04. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- "Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH): Nitrogen Trifluoride". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

External links

- National Pollutant Inventory – Fluoride and compounds fact sheet at the Wayback Machine (archived December 22, 2003)

- WebBook page for NF3

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

| NH3 N2H4 |

He(N2)11 | ||||||||||||||||

| Li3N | Be3N2 | BN | β-C3N4 g-C3N4 CxNy |

N2 | NxOy | NF3 | Ne | ||||||||||

| Na3N | Mg3N2 | AlN | Si3N4 | PN P3N5 |

SxNy SN S4N4 |

NCl3 | Ar | ||||||||||

| K3N | Ca3N2 | ScN | TiN | VN | CrN Cr2N |

MnxNy | FexNy | CoN | Ni3N | CuN | Zn3N2 | GaN | Ge3N4 | As | Se | NBr3 | Kr |

| Rb3N | Sr3N2 | YN | ZrN | NbN | β-Mo2N | Tc | Ru | Rh | PdN | Ag3N | CdN | InN | Sn | Sb | Te | NI3 | Xe |

| Cs3N | Ba3N2 | Hf3N4 | TaN | WN | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg3N2 | TlN | Pb | BiN | Po | At | Rn | |

| Fr3N | Ra3N2 | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn | Nh | Fl | Mc | Lv | Ts | Og | |

| ↓ | |||||||||||||||||

| La | CeN | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | GdN | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | |||

| Ac | Th | Pa | UN | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | Lr | |||