Nigger

In the English language, the word nigger is an ethnic slur typically directed at black people, especially African Americans.

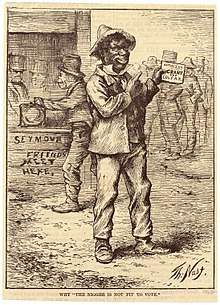

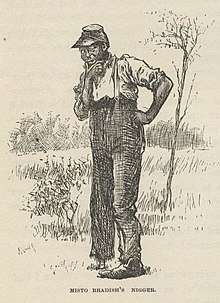

The word originated in the 18th century as an adaptation of the Spanish word negro, a descendant of the Latin adjective niger, which means "black".[1] It was used derogatorily, and by the mid-20th century, particularly in the United States, its usage by anyone other than a black person had become unambiguously pejorative, a racist insult. Accordingly, it began to disappear from general popular culture. Its inclusion in classic works of literature has sparked modern controversy.

Because the term is considered extremely offensive, it is often referred to by the euphemism the N-word. However, it remains in use, particularly as the variant nigga, by African Americans among themselves. The spelling nigga reflects the pronunciation of nigger in non-rhotic dialects of English.

Etymology and history

The variants neger and negar derive from various European languages' words for 'black', including the Spanish and Portuguese word negro (black) and the now-pejorative French nègre, the 'i' entering the spelling "nigger" from those familiar with Latin. Etymologically, negro, noir, nègre, and nigger ultimately derive from nigrum, the stem of the Latin niger ('black'), pronounced [ˈniɡer], with a trilled r. In every grammatical case, grammatical gender, and grammatical number besides nominative masculine singular, is nigr- followed by a case ending.

In its original English-language usage, nigger (then spelled niger) was a word for a dark-skinned individual. The earliest known published use of the term dates from 1574, in a work alluding to "the Nigers of Aethiop, bearing witnes."[2] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first derogatory usage of the term nigger was recorded two centuries later, in 1775.[3]

In the colonial America of 1619, John Rolfe used negars in describing the African slaves shipped to the Virginia colony.[4] Later American English spellings, neger and neggar, prevailed in a northern colony, New York under the Dutch, and in metropolitan Philadelphia's Moravian and Pennsylvania Dutch communities; the African Burial Ground in New York City originally was known by the Dutch name Begraafplaats van de Neger (Cemetery of the Negro); an early occurrence of neger in Rhode Island dates from 1625.[5] Lexicographer Noah Webster, whose eponymous dictionary did much to solidify the distinctive spelling of American English, suggested the neger spelling in place of negro in 1806.[6]

During the fur trade of the early 1800s to the late 1840s in the Western United States, the word was spelled "niggur," and is often recorded in the literature of the time. George Fredrick Ruxton used it in his "mountain man" lexicon, without pejorative connotation. "Niggur" was evidently similar to the modern use of "dude" or "guy." This passage from Ruxton's Life in the Far West illustrates the word in spoken form—the speaker here referring to himself: "Travler, marm, this niggur's no travler; I ar' a trapper, marm, a mountain-man, wagh!"[7] It was not used as a term exclusively for blacks among mountain men during this period, as Indians, Mexicans, and Frenchmen and Anglos alike could be a "niggur."[8] "The noun slipped back and forth from derogatory to endearing."[9]

The term "colored" or "negro" became a respectful alternative. In 1851 the Boston Vigilance Committee, an abolitionist organization, posted warnings to the Colored People of Boston and vicinity. Writing in 1904, journalist Clifton Johnson documented the "opprobrious" character of the word nigger, emphasizing that it was chosen in the South precisely because it was more offensive than "colored" or "negro."[10] By the turn of the century, "colored" had become sufficiently mainstream that it was chosen as the racial self-identifier for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. In 2008 Carla Sims, its communications director, said "the term 'colored' is not derogatory, [the NAACP] chose the word 'colored' because it was the most positive description commonly used [in 1909, when the association was founded]. It's outdated and antiquated but not offensive."[11] Canadian writer Lawrence Hill changed the title of his 2007 novel The Book of Negroes. The name refers to a real historical document, but he felt compelled to find another name for the American market, retitling the US edition Someone Knows My Name.[12]

Nineteenth-century literature features usages of "nigger" without racist connotation. Mark Twain, in the autobiographic book Life on the Mississippi (1883), used the term within quotes, indicating reported speech, but used the term "negro" when writing in his own narrative persona.[13] Joseph Conrad published a novella in Britain with the title The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' (1897), but was advised to release it in the United States as The Children of the Sea, see below. A style guide to British English usage, H. W. Fowler's A Dictionary of Modern English Usage states in the first edition (1926) that applying the word nigger to "others than full or partial negroes" is "felt as an insult by the person described, & betrays in the speaker, if not deliberate insolence, at least a very arrogant inhumanity;" but the second edition (1965) states "N. has been described as 'the term that carries with it all the obloquy and contempt and rejection which whites have inflicted on blacks'."

By the late 1960s, the social change brought about by the civil rights movement had legitimized the racial identity word black as mainstream American English usage to denote black-skinned Americans of African ancestry. President Thomas Jefferson had used this word of his slaves in his Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), but "black" had not been widely used until the later 20th century. (See Black Pride, and, in the context of worldwide anti-colonialism initiatives, Negritude.)

In the 1980s, the term "African American" was advanced analogously to the terms "German American" and "Irish American," and was adopted by major media outlets. Moreover, as a compound word, African American resembles the vogue word Afro-American, an early-1970s popular usage. Some black Americans continue to use the word nigger, often spelled as nigga and niggah, without irony, either to neutralize the word's impact or as a sign of solidarity.[14]

Usage

Surveys from 2006 showed that the American public widely perceived usage of the term to be wrong or unacceptable, but that nearly half of whites and two-thirds of blacks knew someone personally who referred to blacks by the term.[15] Nearly one-third of whites and two-thirds of blacks said they had personally used the term within the last five years.[15]

In names of people, places and things

Political use

"Niggers in the White House"[16] was written in reaction to an October 1901 White House dinner hosted by Republican President Theodore Roosevelt, who had invited Booker T. Washington—an African-American presidential adviser—as a guest. The poem reappeared in 1929 after First Lady Lou Hoover, wife of President Herbert Hoover, invited Jessie De Priest, the wife of African-American congressman Oscar De Priest, to a tea for congressmen's wives at the White House.[17] The identity of the author—who used the byline "unchained poet"—remains unknown.

In explaining his refusal to be conscripted to fight the Vietnam War (1965–75), professional boxer Muhammad Ali said, "No Vietcong [Communist Vietnamese] ever called me nigger;"[18] later, his modified answer was the title No Vietnamese Ever Called Me Nigger (1968) of a documentary about the front-line lot of the U.S. Army Black soldier in combat in Vietnam.[19] An Ali biographer reports that, when interviewed by Robert Lipsyte in 1966, the boxer actually said, "I ain't got no quarrel with them Viet Cong."[20]

On February 28, 2007, the New York City Council symbolically banned the use of the word nigger; however, there is no penalty for using it. This formal resolution also requests excluding from Grammy Award consideration every song whose lyrics contain the word; however, Ron Roecker, vice president of communication for the Recording Academy, doubted it will have any effect on actual nominations.[21][22]

The word can be invoked politically for effect. When Detroit mayor Kwame Kilpatrick came under intense scrutiny for his conduct in 2008, he deviated from an address to the city council, saying, "In the past 30 days, I've been called a nigger more than any time in my entire life." Opponents accused him of "playing the race card" to save his political life.[23]

Cultural use

The implied racism of the word nigger has rendered its use taboo. Magazines and newspapers generally do not use the word but instead print censored versions such as "n*gg*r," "n**ger," "n——" or "the N-word;"[24] see below.

The use of nigger in older literature has become controversial because of the word's modern meaning as a racist insult. One of the most enduring controversies has been the word's use in Mark Twain's novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885). Huckleberry Finn was the fifth most challenged book during the 1990s, according to the American Library Association.[25] The novel is written from the point of view, and largely in the language, of an uneducated white boy, who is drifting down the Mississippi River on a raft with an adult escaped slave, Jim. The word "nigger" is used (mostly about Jim) over 200 times.[26][27] Twain's advocates note that the novel is composed in then-contemporary vernacular usage, not racist stereotype, because Jim, the black man, is a sympathetic character.

In 2011, a new edition published by NewSouth Books replaced the word "nigger" with "slave" and also removed the word "injun." The change was spearheaded by Twain scholar Alan Gribben in the hope of "countering the 'pre-emptive censorship'" that results from the book's being removed from school curricula over language concerns.[28][29] The changes sparked outrage from critics Elon James, Alexandra Petrie and Chris Meadows.[30]

In his 1999 memoir, All Souls, Irish-American Michael Patrick MacDonald describes how many white residents of the Old Colony Housing Project in South Boston used this meaning to degrade the people considered to be of lower status, whether white or black.[31]

Of course, no one considered himself a nigger. It was always something you called someone who could be considered anything less than you. I soon found out there were a few black families living in Old Colony. They'd lived there for years and everyone said that they were okay, that they weren't niggers but just black. It felt good to all of us to not be as bad as the hopeless people in D Street or, God forbid, the ones in Columbia Point, who were both black and niggers. But now I was jealous of the kids in Old Harbor Project down the road, which seemed like a step up from Old Colony ...

In an academic setting

The word's usage in literature has led to it being a point of discussion in university lectures as well. In 2008, Arizona State University English professor Neal A. Lester created what has been called "the first ever college-level class designed to explore the word 'nigger.'"[32] Starting in the following decade, colleges struggled with attempts to teach material about the slur in a sensitive manner. In 2012, a sixth grade Chicago teacher filed a wrongful dismissal lawsuit resulting from an incident in which he repeated the contents of a racially charged note being passed in class.[33] A New Orleans high school also experienced controversy in 2017.[34] Such increased attention prompted Elizabeth Stordeur Pryor, the daughter of Richard Pryor and a professor at Smith College, to give a talk opining that the word was leading to a "social crisis" in higher education.[35]

In addition to Smith College, Emory University, Augsburg University, Southern Connecticut State University and Simpson College all suspended professors in 2019 over referring to the word "nigger" by name in an educational context.[36][37][38] In two other cases, a professor at Princeton decided to stop teaching a course on hate speech after students protested his utterance of "nigger" and a professor at DePaul had his law course cancelled after 80% of the enrolled students transferred out.[39][40] Instead of pursuing disciplinary action, a student at the College of the Desert challenged his professor in a viral class presentation which argued that her use of the word in a lecture was not justified.[41]

In the workplace

In 2018, the head of the media company Netflix, Reed Hastings, fired his chief communications officer for using the word twice during internal discussions about sensitive words.[42] In explaining why, Hastings wrote:

- "[The word's use] in popular media like music and film have created some confusion as to whether or not there is ever a time when the use of the N-word is acceptable. For non-Black people, the word should not be spoken as there is almost no context in which it is appropriate or constructive (even when singing a song or reading a script). There is not a way to neutralize the emotion and history behind the word in any context. The use of the phrase 'N-word' was created as a euphemism, and the norm, with the intention of providing an acceptable replacement and moving people away from using the specific word. When a person violates this norm, it creates resentment, intense frustration, and great offense for many."[43]

The following year, screenwriter Walter Mosley turned down a job after his human resources department took issue with him using the word to describe racism that he experienced as a black man.[44]

While defending Laurie Sheck, a professor who was cleared of ethical violations for quoting I Am Not Your Negro by James Baldwin, John McWhorter wrote that efforts to condemn racist language by white Americans had undergone mission creep.[45] Similar controversies outside the United States have occurred at The University of Western Ontario in Canada and the Madrid campus of the University of Syracuse.[46][47] In June 2020, Canadian news host Wendy Mesley was suspended and replaced with a guest host after she attended a meeting on racial justice and, in the process of quoting a journalist, used "a word that no-one like [her] should ever use."[48]

Intra-group versus intergroup usage

Black listeners often react to the term differently, depending on whether it is used by white speakers or by black speakers. In the former case, it is regularly understood as insensitive or insulting; in the latter, it may carry notes of in-group disparagement, and is often understood as neutral or affectionate, a possible instance of reappropriation.

In the black community, nigger is often rendered as nigga, representing the arhotic pronunciation of the word in African-American English. This usage has been popularized by the rap and hip-hop music cultures and is used as part of an in-group lexicon and speech. It is not necessarily derogatory and is often used to mean homie or friend.[49]

Acceptance of intra-group usage of the word nigga is still debated,[49] although it has established a foothold amongst younger generations. The NAACP denounces the use of both "nigga" and "nigger." Mixed-race usage of "nigga" is still considered taboo, particularly if the speaker is white. However, trends indicate that usage of the term in intragroup settings is increasing even amongst white youth, due to the popularity of rap and hip hop culture.[50]

According to Arthur K. Spears in Diverse Issues in Higher Education, 2006:

In many African-American neighborhoods, nigga is simply the most common term used to refer to any male, of any race or ethnicity. Increasingly, the term has been applied to any person, male or female. "Where y'all niggas goin?" is said with no self-consciousness or animosity to a group of women, for the routine purpose of obtaining information. The point: Nigga is evaluatively neutral in terms of its inherent meaning; it may express positive, neutral, or negative attitudes;[51]

Kevin Cato, meanwhile, observes:

For instance, a show on Black Entertainment Television, a cable network aimed at a black audience, described the word nigger as a "term of endearment". "In the African American community, the word nigga (not nigger) brings out feelings of pride." (Davis 1). Here the word evokes a sense of community and oneness among black people. Many teens I interviewed felt that the word had no power when used amongst friends, but when used among white people the word took on a completely different meaning. In fact, comedian Alex Thomas on BET stated, "I still better not hear no white boy say that to me ... I hear a white boy say that to me, it means 'White boy, you gonna get your ass beat.'"[52]

Addressing the use of nigger by black people, philosopher and public intellectual Cornel West said in 2007:

There's a certain rhythmic seduction to the word. If you speak in a sentence, and you have to say cat, companion, or friend, as opposed to nigger, then the rhythmic presentation is off. That rhythmic language is a form of historical memory for black people ... When Richard Pryor came back from Africa, and decided to stop using the word onstage, he would sometimes start to slip up, because he was so used to speaking that way. It was the right word at the moment to keep the rhythm together in his sentence making.[53]

2010s: increase in use and controversy

In the 2010s, "nigger" in its various forms saw use with increasing frequency by African Americans amongst themselves or in self-expression, the most common swear word in hip hop music lyrics.[54][55] Ta-Nehisi Coates suggested that it continues to be unacceptable for non-blacks to utter while singing or rapping along to hip-hop, and that by being so restrained it gives white Americans (specifically) a taste of what it is like to not be entitled to "do anything they please, anywhere." A concern often raised is whether frequent exposure will inevitably lead to a dilution of the extremely negative perception of the word among the majority of non-black Americans who currently consider its use unacceptable and shocking.[56]

Related words

Derivatives

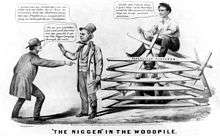

In several English-speaking countries, "Niggerhead" or "nigger head" was used as a name for many sorts of things, including commercial products, places, plants and animals, as described above. It also is or was a colloquial technical term in industry, mining, and seafaring. Nigger as "defect" (a hidden problem), derives from "nigger in the woodpile," a US slave-era phrase denoting escaped slaves hiding in train-transported woodpiles.[57] In the 1840s, the Morning Chronicle newspaper report series London Labour and the London Poor, by Henry Mayhew, records the usages of both "nigger" and the similar-sounding word "niggard" denoting a false bottom for a grate.[58]

In American English, "nigger lover" initially applied to abolitionists, then to white people sympathetic towards black Americans.[59] The portmanteau word wigger (white + nigger) denotes a white person emulating "street black behavior," hoping to gain acceptance to the hip hop, thug, and gangsta sub-cultures. Norman Mailer wrote of the antecedents of this phenomenon in 1957 in his essay "The White Negro."

The N-word euphemism

— Kenneth B. Noble, January 14, 1995 The New York Times[61]

The euphemism the N-word became mainstream American English usage during the racially contentious O. J. Simpson murder case in 1995.

Key prosecution witness Detective Mark Fuhrman, of the Los Angeles Police Department – who denied using racist language on duty – impeached himself with his prolific use of nigger in tape recordings about his police work. The recordings, by screenplay writer Laura McKinney, were from a 1985 research session wherein the detective assisted her with a screenplay about LAPD policewomen. Fuhrman excused his use of the word saying he used nigger in the context of his "bad cop" persona. Media personnel who reported on Fuhrman's testimony substituted the N-word for nigger.

Homophones

Niger (Latin for "black") occurs in Latinate scientific nomenclature and is the root word for some homophones of nigger; sellers of niger seed (used as bird feed), sometimes use the spelling Nyjer seed. The classical Latin pronunciation /ˈniɡeɾ/ sounds like the English /ˈnɪɡər/, occurring in biologic and anatomic names, such as Hyoscyamus niger (black henbane), and even for animals that are in fact not black, such as Sciurus niger (fox squirrel).

Nigra is the Latin feminine form of niger (black), used in biologic and anatomic names such as substantia nigra (black substance).

The word niggardly (miserly) is etymologically unrelated to nigger, derived from the Old Norse word nig (stingy) and the Middle English word nigon. In the US, this word has been misinterpreted as related to nigger and taken as offensive. In January 1999, David Howard, a white Washington, D.C., city employee, was compelled to resign after using niggardly—in a financial context—while speaking with black colleagues, who took umbrage. After reviewing the misunderstanding, Mayor Anthony Williams offered to reinstate Howard to his former position. Howard refused reinstatement but took a job elsewhere in the mayor's government.[62]

Denotational extension

The denotations of nigger also comprehend non-black/non-white and other disadvantaged people. Some of these terms are self-chosen, to identify with the oppression and resistance of black Americans; others are ethnic slurs used by outsiders.

Jerry Farber's 1967 essay, The Student as Nigger, used the word as a metaphor for what he saw as the role forced on students. Farber had been, at the time, frequently arrested as a civil rights activist while beginning his career as a literature professor.

In his 1968 autobiography White Niggers of America: The Precocious Autobiography of a Quebec "Terrorist," Pierre Vallières, a Front de libération du Québec leader, refers to the oppression of the Québécois people in North America.

In 1969, in the course of being interviewed by the British magazine Nova, artist Yoko Ono said "woman is the nigger of the world;" three years later, her husband, John Lennon, published the song of the same name—about the worldwide phenomenon of discrimination against women—which was socially and politically controversial to US sensibilities.

Sand nigger, an ethnic slur against Arabs, and timber nigger and prairie nigger, ethnic slurs against Native Americans, are examples of the racist extension of nigger upon other non-white peoples.[63]

In 1978 singer Patti Smith used the word in "Rock N Roll Nigger."

In 1979 English singer Elvis Costello used the phrase white nigger in "Oliver's Army," a song describing the experiences of working-class soldiers in the British military forces on the "murder mile" (Belfast during The Troubles), where white nigger was a common British pejorative for Irish Catholics. Later, the producers of the British talent show Stars in Their Eyes forced a contestant to censor one of its lines, changing "all it takes is one itchy trigger – One more widow, one less white nigger" to "one less white figure."

Historian Eugene Genovese, noted for bringing a Marxist perspective to the study of power, class, and relations between planters and slaves in the South, uses the word pointedly in The World the Slaveholders Made (1988).

For reasons common to the slave condition all slave classes displayed a lack of industrial initiative and produced the famous Lazy Nigger, who under Russian serfdom and elsewhere was white. Just as not all blacks, even under the most degrading forms of slavery, consented to become niggers, so by no means all or even most of the niggers in history have been black.

The editor of Green Egg, a magazine described in The Encyclopedia of American Religions as a significant periodical, published an essay entitled "Niggers of the New Age." This argued that Neo-Pagans were treated badly by other parts of the New Age movement.[64]

Other languages

Other languages, particularly Romance languages, have words that sound similar to 'nigger' (are homophones), but do not mean the same. Just because the words are cognate, i.e. from the same Latin stem as explained above, does not mean they have the same denotation (dictionary meaning) or connotation (emotional association). Whether a word is abusive, pejorative, neutral, affectionate, old-fashioned, etc. depends on its cultural context. How a word is used in English does not determine how a similar-sounding word is used in another language. Conversely, many languages have ethnic slurs that disparage "other" people, i.e. words that serve a similar function to "nigger," but these usually stem from completely different roots.

Some examples of how other languages refer to a black person in a neutral and in a pejorative way include:

- Dutch: Neger ("Negro") used to be neutral, but many now consider it to be avoided in favor of zwarte ("black").[65][66][67][68] Zwartje (little black one) can be amicably or offensively used. Nikker is always pejorative.[69]

- French: Nègre (see the French Wikipedia) is now derogatory. Some white Frenchmen have the inherited surname "Nègre": see Nègre (homonymie) (a disambiguation page). The word can still be used as a synonym of "sweetheart" in some traditional Louisiana French creole songs.[70]

- German: Neger is dated and now considered offensive. Schwarze/-r ("black [person]") or Farbige/-r ("colored [person]") is more neutral but increasingly also dated.

- Haitian Creole: nèg is used for any man in general, regardless of skin color (like "dude" in American English). Haitian Creole derives predominantly from French.

- Italian has three variants : "negro," "nero" and "di colore." The first one is the most historically attested and was the most commonly used until the 1960s as an equivalent of the English word negro. It was gradually felt as offensive during the 1970s and replaced with "nero" and "di colore." "Nero" was considered a better translation of the English word "black," while "di colore" is a loan translation of the English word "colored"[71]

- Brazilian Portuguese: Negro and preto are neutral;[72] nevertheless preto can be offensive or at least "politically incorrect" and is almost never proudly used by Afro-Brazilians. Crioulo and macaco are always extremely pejorative.[73]

- In the Russian language, негр (negr) is a common word for black people. A word чёрный (chyornyi, black) can be used as derogatory word for peoples of the Caucasus and, less often, black people.

See also

- List of ethnic slurs

- List of ethnic group names used as insults

- Kaffir (ethnic slur)

- Blackfella

- Murzyn, Polish word for a black person

- N-word (disambiguation)

- Cultural appropriation

- Guilty or Innocent of Using the N Word, a 2006 documentary

- List of topics related to Black and African people

- Profanity

- Reappropriation

- Taboo

- "With Apologies to Jesse Jackson", an episode of the animated comedy series South Park, in which Stan's dad, Randy, becomes a social pariah after using the word (albeit reluctantly) on national television

- Golliwog

Footnotes

- Pilgrim, David (September 2001). "Nigger and Caricatures". Retrieved June 19, 2007.

- Patricia T. O'Conner, Stewart Kellerman (2010). Origins of the Specious: Myths and Misconceptions of the English Language. Random House Publishing Group. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-8129-7810-0. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Peterson, Christopher (2013). Bestial Traces:Race, Sexuality, Animality: Race, Sexuality, Animality. Fordham Univ Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8232-4520-8. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Randall Kennedy (January 11, 2001). "Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 17, 2007. (Book review)

- Hutchinson, Earl Ofari (1996). The Assassination of the Black Male Image. Simon and Schuster. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-684-83100-8.

- Mencken, H. L. (1921). "Chapter 8. American Spelling > 2. The Influence of Webster". The American Language: An Inquiry into the Development of English in the United States (2nd rev. and enl. ed.). New York: A.A. Knopf.

- Ruxton, George Frederick (1846). Life In the Far West. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-1534-4.

- "Language of the Rendezvous". Archived from the original on December 20, 2012.

- Coleman, Jon (2012). Here Lies Hugh Glass: A Mountain Man, a Bear, and the Rise of the American Nation. Macmillan. p. 272. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- Johnson, Clifton (October 14, 1904). "They Are Only "Niggers" in the South". The Seattle Republican. Seattle, Wash.: Republican Pub. Co. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- "Lohan calls Obama 'colored', NAACP says no big deal". Mercury News. November 12, 2008.

- Hill, Lawrence (May 20, 2008). "Why I'm not allowed my book title". The Guardian. Retrieved October 9, 2019 – via www.theguardian.com.

- Twain, Mark (1883). Life on the Mississippi. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 75. James R. Osgood & Co., Boston (U.S. edition). p. 11,13,127,139,219. doi:10.1097/00001888-200010000-00016. ISBN 978-0-486-41426-3. PMID 11031147.

- Allan, Keith. The Pragmatics of Connotation. Journal of Pragmatics 39:6 (June 2007) 1047–57

- "Using the n-word is more common than you (or President Obama) may think". Washington Post. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- "Niggers in the White House". Theodore Roosevelt Center, Dickinson State University. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- Jones, Stephen A.; Freedman, Eric (2011). Presidents and Black America: A Documentary History. Los Angeles: CQ Press. p. 349. ISBN 9781608710089.

- Kennedy, Randall (2002). Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word. Random House. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-375-42172-3.

- Rollins, Peter C. (2003). The Columbia Companion to American History on Film: How the Movies Have Portrayed the American Past. Columbia UP. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-231-11222-2.

- Lemert, Charles (2003). Muhammad Ali: Trickster in the Culture of Irony. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 105–107. ISBN 978-0-7456-2871-4.

- Ed Pilkington (March 1, 2007). "New York city council bans use of the N-word". The Guardian Unlimited. London. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- "Res. No. 693-A – Resolution declaring the NYC Council's symbolic moratorium against using the "N" word in New York City". New York City Council. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- French, Ron (March 13, 2008). "Attorney General Cox: Kilpatrick should resign". detnews.com. The Detroit News. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- "Nigger Usage Alert". dictionary.com. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- "100 most frequently challenged books: 1990–1999". ala.org. March 27, 2013.

- "Adventures Of Huckleberry Finn". The Complete Works of Mark Twain. Archived from the original on September 9, 2006. Retrieved March 12, 2006.

- "Academic Resources: Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word". Random House. Archived from the original on January 22, 2007. Retrieved March 13, 2006. Alt URL

- Page, Benedicte (January 5, 2011). "New Huckleberry Finn edition censors 'n-word'". the Guardian.

- Twain, Mark (January 7, 2011). "'The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn' – Removing the N Word from Huck Finn: Top 10 Censored Books". TIME. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- The Christian Science Monitor (January 5, 2011). "The 'n'-word gone from Huck Finn – what would Mark Twain say?". The Christian Science Monitor.

- MacDonald, Michael Patrick. All Souls: A Family Story from Southie Publisher Random House, Inc., 2000. Page 61. ISBN 978-0-345-44177-5, 9780345441775

- Price, Sean (2011). "Straight talk about the N-word". Teaching Tolerance. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- Kaminer, Wendy (February 21, 2012). "Can educators ever teach the N-word?". The Atlantic. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- O'Sullivan, Donie (May 5, 2017). "School reflects on race after student-teacher N-word exchange". CNN. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- Moulton, Cyrus (September 19, 2019). "Elizabeth Stordeur Pryor says use of the N-word is causing social crisis". Telegram & Gazette. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- Patrice, Joe (October 4, 2019). "The original Emory Law School N-word using professor faces hearing on his future today". Above The Law. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- Stein, Matthew (April 11, 2019). "Universities repeatedly discipline professors for referring to the n-word". The College Fix. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- Flaherty, Colleen (November 18, 2019). "Professor won't teach more classes after saying N-word". Inside Higher Education. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- Dwyer, Colin (February 13, 2018). "Professor cancels course on hate speech amid contention over his use of slur". NPR. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- Lee, Ella (September 23, 2019). "Professor formerly under fire for use of 'N-word' in teaching exercise back at DePaul". DePaulia. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- Harvard, Sarah (March 7, 2019). "College student delivers presentation to call out professor for using n-word in class". The Independent. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- Mele, Christopher (June 23, 2018). "Netflix Fires Chief Communications Officer Over Use of Racial Slur". The New York Times. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- Landy, Heather (June 23, 2018). "Read the Netflix CEO's excellent memo about firing an executive who used the N-word". Quartz at Work. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- Mosley, Walter (September 6, 2019). "Why I quit the writer's room". The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- McWhorter, John (August 21, 2019). "The idea that white's can't refer to the N-word". The Atlantic. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- Lebel, Jacquelyn (October 28, 2019). "Western University professor apologizes after student calls out his use of the n-word". Global News. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- Leffert, Catherine (March 13, 2019). "Students, professor use 'N-word' during class at SU's Madrid program". The Daily Orange. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- Calabrese, Darren (June 9, 2020). "CBC host Wendy Mesley apologizes for using a certain word in discussion on race". The Canadian Press. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- "Nigga Usage Alert". dictionary.com. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- Kevin Aldridge, Richelle Thompson and Earnest Winston. "The evolving N-word." The Cincinnati Enquirer, August 5, 2001.

- Spears, Dr. Arthur K. (July 12, 2006). "Perspectives: A View of the 'N-Word' from Sociolinguistics". Diverse Issues in Higher Education.

- "Nigger". Wrt-intertext.syr.edu. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- Mohr, Tim (November 2007). "Cornel West Talks Rhymes and Race". Playboy. 54 (11): 44.

- Sheinin, Dave (November 9, 2014). "Redefining the Word". Washington Post. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- "Profanity in lyrics: most used swear words and their usage by popular genres". Musixmatch. December 16, 2015. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- Bain, Marc (November 13, 2017). "Ta-Nehisi Coates Gently Explains Why White People Can't Rap the N-Word". Quartz. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- The Oxford English Reference Dictionary, second edition, (1996) p. 981

- vol 2 p6

- "The Color of Words", by Philip Herbst, 1997, ISBN 978-1-877864-97-1, p. 166

- Arac, Jonathan (November 1997). Huckleberry Finn as idol and target. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-299-15534-6. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- Noble, Kenneth B. (January 14, 1995). "Issue of Racism Erupts in Simpson Trial". The New York Times.

- Yolanda Woodlee (February 4, 1999). "D.C. Mayor Acted 'Hastily,' Will Rehire Aide". Washington Post. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Kennedy, Randall L. (Winter 1999–2000). "Who Can Say "Nigger"? And Other Considerations". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (26): 86–96 [87]. doi:10.2307/2999172. JSTOR 2999172.

- G'Zell, Otter (2009). Green Egg Omelette: An Anthology of Art and Articles from the Legendary Pagan Journal. p. 209. ASIN 1601630468.CS1 maint: ASIN uses ISBN (link)

- Waarom wil je ons zo graag neger noemen?, joop.nl, 25 mei 2014

- "Neger/zwarte", Taaltelefoon.

- Style guide of de Volkskrant "Volkskrant stijlboek". Volkskrant. Volkskrant. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- Style guide of NRC Handelsblad "Stijlboek". NRC handelsblad. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- Van Dale, Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse taal, 2010

- "Le Son des Français d'Amérique – Les Créoles". Retrieved October 9, 2019 – via www.youtube.com.

- Accademia della Crusca, Nero, negro e di colore, 12 ottobre 2012 [IT]

- "Tabela 1.2 – População residente, por cor ou raça, segundo a situação do domicílio e o sexo – Brasil – 2009" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. and "Evolutio da populaco brasileira, segundo a cor – 1872/1991". Archived from the original on December 21, 2010.

- "G1 > Edição Rio de Janeiro – NOTÍCIAS – Sou incapaz de qualquer atitude racista, diz procurador". g1.globo.com. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

References

- "nigger". The Oxford English Dictionary (2 ed.). 1989.

- Fuller, Neely Jr. (1984). The United Independent Compensatory Code/System/Concept: A Textbook/Workbook for Thought, Speech, and/or Action, for Victims of Racism (white supremacy). ASIN B000BVZW38.

- Kennedy, Randall (2002). Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-42172-3.

- Smith, Stephanie (2005). Household Words: Bloomers, Sucker, Bombshell, Scab, Nigger, Cyber. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-4552-7.

- Swan, Robert J. (2003). New Amsterdam Gehenna: Segregated Death in New York City, 1630–1801. Brooklyn: Noir Verite Press. ISBN 978-0-9722813-0-0.

- Worth, Robert F. (Fall 1995). "Nigger Heaven and the Harlem Renaissance". African American Review. 29 (3): 461–473. doi:10.2307/3042395. JSTOR 3042395.

Further reading

| Look up nigger or N-word in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Asim, Jabari (2007). The N Word: who can say it, who shouldn't, and why. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-618-19717-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)