Use of nigger in the arts

This article treats usage of the word nigger (now widely considered a racial slur) in reference to African Americans and others of African or mixed African and other ethnic origin in the art of Western culture and the English language.

Literature

The use of nigger in older literature has become controversial because of the word's modern meaning as a racist insult.

In the title

Our Nig: Sketches from the Life of a Free Black is an autobiographical novel by Harriet E. Wilson, a free Negro herself. It was published in 1859[1] and rediscovered in 1981 by literary scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr. It is believed to be the first novel published by an African-American woman on the North American continent.[2][3]

In 1897, Joseph Conrad penned a novella titled The Nigger of the 'Narcissus', whose titular character, James Wait, is a West Indian black sailor on board the merchant ship Narcissus sailing from Bombay to London. In the United States, the novel was first published with the title The Children of the Sea: A Tale of the Forecastle, at the insistence by the publisher, Dodd, Mead and Company, that no one would buy or read a book with the word "nigger" in its title,[4] not because the word was deemed offensive but that a book about a black man would not sell.[5] In 2009, WordBridge Publishing published a new edition titled The N-Word of the Narcissus, which also excised the word "nigger" from the text. According to the publisher, the point was to get rid of the offensive word, which may have led readers to avoid the book, and make it more accessible.[6] Though praised in some quarters, many others denounced the change as censorship.

The writer and photographer Carl Van Vechten took the opposite view to Conrad's publishers when he advised the British novelist Ronald Firbank to change the title of his 1924 novel Sorrow in Sunlight to Prancing Nigger for the American market,[7] and it became very successful there under that title.[8] Van Vechten, a white supporter of the Harlem Renaissance (1920s–30s), then used the word himself in his 1926 novel Nigger Heaven, which provoked controversy in the black community. Of the controversy, Langston Hughes wrote:

No book could possibly be as bad as Nigger Heaven has been painted. And no book has ever been better advertised by those who wished to damn it. Because it was declared obscene, everybody wanted to read it, and I'll venture to say that more Negroes bought it than ever purchased a book by a Negro author. Then, as now, the use of the word nigger by a white was a flashpoint for debates about the relationship between black culture and its white patrons.

Ten Little Niggers was the original title of Agatha Christie's 1939 detective novel, named for a children's counting-out game familiar in England at that date; it was renamed first to Ten Little Indians and then in the early 1980s to And Then There Were None.[9][10]

Flannery O'Connor uses a black lawn jockey as a symbol in her 1955 short story "The Artificial Nigger". American comedian Dick Gregory used the word in the title of his 1964 autobiography, written during the American Civil Rights Movement. Gregory comments on his choice of title in the book's primary dedication: "if ever you hear the word "nigger" again, remember they are advertising my book.[11] Labi Siffre, the singer-songwriter best known for "(Something Inside) So Strong", entitled his first book of poetry simply Nigger (Xavier Books 1993). The use of nigger in older literature has become controversial because of the word's modern meaning as a racist insult.

Huckleberry Finn

Mark Twain's novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885) has long been the subject of controversy for its racial content. Huckleberry Finn was the fifth most challenged book during the 1990s, according to the American Library Association.[12] The novel is written from the point of view, and largely in the language, of Huckleberry Finn, an uneducated white boy, who is drifting down the Mississippi River on a raft with an adult escaped slave, Jim. The word "nigger" is used (mostly about Jim) over 200 times.[13][14] Twain's advocates note that the novel is composed in then-contemporary vernacular usage, not racist stereotype, because Jim, the black man, is a sympathetic character.

In 2011, a new edition published by NewSouth Books replaced the word "nigger" with "slave" and also removed the word "injun". The change was spearheaded by Twain scholar Alan Gribben in the hope of "countering the 'pre-emptive censorship'" that results from the book's being removed from school curricula over language concerns.[15][16] The changes sparked outrage from critics Elon James, Alexandra Petrie and Chris Meadows.[17]

British literary usage

.jpg)

Several late-nineteenth- and early twentieth-century British literary usages suggest neutral usage. The popular Victorian era entertainment, the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta The Mikado (1885), twice uses the word nigger. In the song As some day it may happen, the executioner, Ko-ko, sings of executing the "nigger serenader and the others of his race", referring to white singers with their faces blacked singing minstrel songs. In the song A more humane Mikado, the Mikado sings of the punishment for older women who dye their hair or wear corsets, to be "Blacked like a nigger/With permanent walnut juice." Both lyrics are usually changed for modern performances.[18]

The word "nigger" appears in children's literature. "How the Leopard Got His Spots", in the Just So Stories (1902) by Rudyard Kipling, tells of an Ethiopian man and a leopard, both originally sand-colored, deciding to camouflage themselves with painted spots, for hunting in tropical forest. The story originally included a scene wherein the leopard (now spotted) asks the Ethiopian man why he does not want spots. In contemporary editions of "How the Leopard Got His Spots", the Ethiopian's original reply ("Oh, plain black's best for a nigger") has been edited to, "Oh, plain black's best for me." The counting rhyme known as "Eenie Meenie Mainee, Mo" has been attested from 1820, with many variants; when Kipling included it as "A Counting-Out Song" in Land and Sea Tales for Scouts and Guides (1923), he gave as its second line, "Catch a nigger by the toe!" This version became widely used for much of the twentieth century; the rhyme is still in use, but the second line now uses "tiger" instead.

The word "nigger" is used innocently and without malice by the child characters in some of the Swallows and Amazons series, written in the 1930s by Arthur Ransome, e.g. in referring to how the (white) characters appear in photographic negatives ("Look like niggers to me") in The Big Six, and as a synonym for black pearls in Peter Duck. Editions published by Puffin after Ransome's death changed the word to 'negroes'.

The first Jeeves novel, Thank You, Jeeves (1934), features a minstrel show as a significant plot point. Bertie Wooster, who is trying to learn to play the banjo, is in admiration of their artistry and music. Tellingly, P.G. Wodehouse has the repeated phrase "nigger minstrels" only on the lips of Wooster and his peers; the manservant Jeeves uses the more genteel "Negroes".

In short story "The Basement Room" (1935), by Graham Greene, the (sympathetic) servant character, Baines, tells the admiring boy, son of his employer, of his African British colony service, "You wouldn't believe it now, but I've had forty niggers under me, doing what I told them to". Replying to the boy's question: "Did you ever shoot a nigger?" Bains answers: "I never had any call to shoot. Of course I carried a gun. But you didn't need to treat them bad, that just made them stupid. Why, I loved some of those dammed niggers." The cinematic version, The Fallen Idol (1948), directed by Carol Reed, replaced this usage with "natives".

Virginia Woolf, in her 1941 posthumously-published novel Between the Acts, wrote "Down amongst the bushes she worked like a nigger." The phrase is not dialogue from one of the characters, nor is it in the context of expressing a point of view of one of the characters.[19] Woolf's usage of racist slurs has been examined in various academic writings.[20]

The Reverend W. V. Awdry's The Railway Series (1945–72) story Henry's Sneeze, originally described soot-covered boys with the phrase "as black as niggers".[21] In 1972, after complaints, the description was edited to "as black as soot", in the subsequent editions.[21] Rev. Awdry is known for Thomas the Tank Engine (1946).

Music

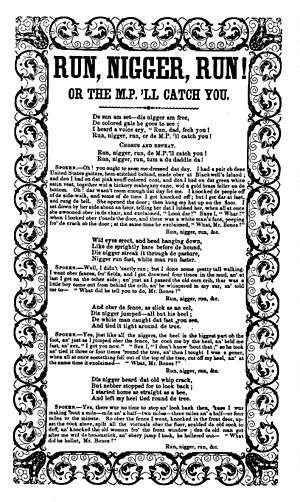

The folk song "Oh! Susanna" by Stephen Foster had originally been written in four verses. The second verse describes an industrial accident which "kill'd five hundred Nigger" by electrocution.

The 1932 British song "The Sun Has Got His Hat On" originally included the line "He's been tanning niggers out in Timbuktu" (where "He" is the sun). Modern recordings substitute other lines.

The Bohemian composer Antonín Dvořák wrote the String Quartet No. 12 in 1893 during his time in the United States. For its presumed association with African-American music, the quartet was referred to until the 1950s with nicknames such as "Negro Quartet" and "Nigger Quartet" before being called the "American Quartet".

In the 1960s, record producer J. D. "Jay" Miller published pro-racial segregation music, with the "Reb Rebel" label featuring racist songs by Johnny Rebel and others, demeaning black Americans and the Civil Rights Movement.[22] The country music artist David Allan Coe used the racial terms "redneck", "white trash", and "nigger" in the songs "If That Ain't Country, I'll Kiss Your Ass" and "Nigger Fucker".[23]

In 1972 John Lennon and Yoko Ono used the word in both the title and in the chorus of their song "Woman Is the Nigger of the World," which was released as both a single and a track on their album "Sometime in New York City." [24]

On Bob Marley and the Wailers' 1973 song "Get Up, Stand Up", Marley can be heard singing the line, "Don't be a nigger in your neighborhood" during the outro.

In 1975 Bob Dylan used the word in his song "Hurricane".

In 1978 Patti Smith used the word prominently in her song "Rock N Roll Nigger".

The punk band the Dead Kennedys used the word in their 1980 song "Holiday in Cambodia" in the line, "Bragging that you know how the niggers feel cold and the slum's got so much soul". The context is a section mocking champagne socialists. Rap groups such as N.W.A (Niggaz with Attitudes) re-popularized the usage in their songs. One of the earliest uses of the word in hip hop was in the song "New York New York" by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five in 1983. Responding to accusations of racism after referring to "niggers" in the lyrics of the 1988 Guns N' Roses song, "One in a Million", Axl Rose stated: "I was pissed off about some black people that were trying to rob me. I wanted to insult those particular black people. I didn't want to support racism."[25]

The term white nigger is also used in music, most notably in Elvis Costello's song "Oliver's Army", see below.

Since the 2010s the word nigger has been used with increasing frequency[26] by African Americans amongst themselves or in self-expression, the most common swear word in hip hop music lyrics.[27] As a result, it is a word that is heard daily by millions of all races worldwide who listen to uncensored hip hop and other music genres, while being socially unacceptable for anyone but African Americans to utter. Ta-Nehisi Coates has suggested that it continues to be unacceptable for people who are not of African ancestry to utter the word nigger while singing or rapping along to hip-hop, and that by being so restrained it gives White Americans (specifically) a taste of what it's like to not be entitled to "do anything they please, anywhere". Counterpoint to this standpoint is the open question of whether daily, frequent exposure by non-Black Americans to African Americans using the word will inevitably lead to a dilution of the extremely negative perception of the word among the majority of non-Black Americans that currently consider its use unacceptable and shocking.[28]

Theater

The musical Show Boat, which subverts anti-miscegenation laws, from 1927 until 1946 features the word "nigger" as originally integral to the lyrics of "Ol' Man River" and "Cotton Blossom"; although deleted from the cinema versions, it is included in the 1988 EMI recording of the original score. Musical theatre historian Miles Kreuger and conductor John McGlinn propose that the word was not an insult, but a blunt illustration of how white people then perceived black people.

The Moore's Ford lynchings, also known as the 1946 Georgia lynching, has been commemorated since 2005 with a yearly re-enactment. According to a volunteer actor playing one of the victims, this living memorial "consist[s] largely of older white men calling him “nigger,” tying a noose around his neck, and pretending to shoot him repeatedly"[29]

Cinema

One of Horace Ové's first films was Baldwin's Nigger (1968), in which two African Americans, novelist James Baldwin and comedian Dick Gregory, discuss Black experience and identity in Britain and the United States.[30] Filmed at the West Indian Students' Centre in London, the film documents a lecture by Baldwin and a question-and-answer session with the audience.[31][32]

Mel Brooks' 1974 satirical Western film Blazing Saddles used the term repeatedly. In The Kentucky Fried Movie (1977), the sequence titled "Danger Seekers" features a stuntman performing the dangerous act of shouting "Niggers!" at a group of black people, then fleeing when they take chase.

Stanley Kubrick's critically acclaimed 1987 war film Full Metal Jacket depicts black and white U.S. Marines enduring boot camp and later fighting together in Vietnam. "Nigger" is used by soldiers of both races in jokes and as expressions of bravado ("put a nigger behind the trigger", says the black Corporal "Eightball"), with racial differences among the men seen as secondary to their shared exposure to the dangers of combat: Gunnery Sergeant Hartman (R. Lee Ermey) says, "There is no racial bigotry here. I do not look down on niggers, kikes, wops or greasers. Here you are all equally worthless."

Gayniggers from Outer Space, a 1992 English-language Danish short blaxploitation parody, features black homosexual male aliens who commit gendercide to free the men of Earth from female oppression. Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995) featured a scene where villain Simon Gruber (Jeremy Irons) required New York City Police Department Lt. John McClane (Bruce Willis) to wear a sandwich board reading "I hate niggers" while standing on a street corner in predominantly-black Harlem, resulting in McClane meeting Zeus Carver (Samuel L. Jackson) as Carver rescued McClane from being attacked by neighborhood toughs.

American filmmaker Quentin Tarantino has been criticized[33] for the heavy usage of the word nigger in his films, especially Jackie Brown (1997), where the word is used 38 times[34] and Django Unchained (2012), used 110 times.[35]

The Dam Busters

During World War II, a dog called Nigger, a black Labrador belonged to Royal Air Force Wing Commander Guy Gibson.[36] In 1943, Gibson led the successful Operation Chastise attack on dams in Nazi Germany. The dog's name was used as a single codeword whose transmission conveyed that the Möhne dam had been breached. In Michael Anderson's 1955 film The Dam Busters, based on the raid, the dog was portrayed in several scenes; his name and the codeword were mentioned several times. Some of the these scenes were sampled in Alan Parker's 1982 film Pink Floyd – The Wall.[37]

In 1999, British television network ITV broadcast a censored version with each of the twelve[38] utterances of Nigger deleted. Replying to complaints against its censorship, ITV blamed the regional broadcaster, London Weekend Television, which, in turn, blamed a junior employee as the unauthorised censor. In June 2001, when ITV re-broadcast the censored version of The Dam Busters, Index on Censorship criticised it as "unnecessary and ridiculous" censorship breaking the continuity of the film and the story.[39] In January 2012, the film was shown uncensored on ITV4, but with a warning at the start that the film contained racial terms from the historical period which some people could find offensive. Versions edited for US television have the dog's name altered to "Trigger".[38]

In 2008, New Zealand filmmaker Peter Jackson announced that he was spearheading a remake. Screenwriter Stephen Fry said there was "no question in America that you could ever have a dog called the N-word". In the unrealized remake, the dog was to be renamed "Digger".[40]

Stand-up comedy

Some comedians have broached the subject, almost invariably in the form of social commentary. This was perhaps most famously done by stand-up comedian Chris Rock in his "Niggas vs. Black People" routine.[41] Richard Pryor used to use "nigger" extensively, but later in life decided to restrict himself to "motherfucker".[42][43]

References

- Wilson, Harriet E. (2004) [1859]. Our Nig: Sketches From The Life Of A Free Black. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4000-3120-6. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- Interview with Henry Louis Gates (mp3) Archived May 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Gates and a literary critic discuss Our Nig, Wired for Books

- Our Nig: Sketches from the Life of a Free Black, Geo. C. Rand and Avery, 1859.

- Orr, Leonard (1999). A Joseph Conrad Companion. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-29289-7.

- "Children of the Sea|The – Sumner & Stillman". Sumnerandstillman.com. December 1, 2006. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- Joseph Conrad, foreword by Ruben Alvarado (December 2009). The N-word of the Narcissus. WorldBridge. ISBN 9789076660110.

- Bernard, Emily (2012). Carl Van Vechten and the Harlem Renaissance. Yale University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780300183290.

- Jocelyn Brooke. "Novels of Ronald Firbank by Jocelyn Brooke". ourcivilisation.com.

- Peers, C; Spurrier A & Sturgeon J (1999). Collins Crime Club – A checklist of First Editions (2nd ed.). Dragonby Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-871122-13-8.

- Pendergast, Bruce (2004). Everyman's Guide To The Mysteries Of Agatha Christie. Victoria, BC: Trafford Publishing. p. 393. ISBN 978-1-4120-2304-7.

- "Dick Gregory Global Watch - About Dick Gregory". Dickgregory.com. 1932-10-12. Archived from the original on 2007-06-17. Retrieved 2013-10-08.

- "100 most frequently challenged books: 1990–1999". ala.org. March 27, 2013.

- "Adventures Of Huckleberry Finn". The Complete Works of Mark Twain. Archived from the original on September 9, 2006. Retrieved March 12, 2006.

- "Academic Resources: Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word". Random House. Archived from the original on January 22, 2007. Retrieved March 13, 2006. Alt URL

- "New Huckleberry Finn edition censors 'n-word'". the Guardian.

- Twain, Mark (January 7, 2011). "'The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn' – Removing the N Word from Huck Finn: Top 10 Censored Books". TIME. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- The Christian Science Monitor (January 5, 2011). "The 'n'-word gone from Huck Finn – what would Mark Twain say?". The Christian Science Monitor.

- Michael Sragow (December 23, 1999). "The roar of the greasepaint, the smell of the crowd". Archived from the original on February 14, 2005. Retrieved March 13, 2006.

- Woolf, Virginia (1949). Between the Acts. Rome: Albatross. p. 175.

- Lee, Hermione: "Virginia Woolf and Offence," in The Art of Literary Biography, Oxford Scholarship Online: October 2011; reviewed by McManus, Patricia: "The "Offensiveness" of Virginia Woolf: From a Moral to a Political Reading" in Woolf Studies Annual, vol. 14, Annual 2008.

- Sibley, Brian (1995). The Thomas the Tank Engine Man. London: Heinemann. pp. 272–5. ISBN 978-0-434-96909-8.

- John Broven, South to Louisiana: The Music of the Cajun Bayous. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican, 1983, p. 252f.

- Myspace.com David Allen Coe

- Duston, Anne. "Lennon, Ono 45 Controversial" Billboard 17 June 1972: 65

- MNeely, Kim (April 2, 1992). "Axl Rose: The RS Interview". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- Sheinin, Dave (November 9, 2014). "Redefining the Word". Washington Post. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- "Profanity in lyrics: most used swear words and their usage by popular genres". Musixmatch. December 16, 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- Bain, Marc (November 13, 2017). "Ta-Nehisi Coates Gently Explains Why White People Can't Rap the N-Word". Quartz. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- Baker, Peter C. (November 2, 2016). "A lynching in Georgia: the living memorial to America's history of racist violence". The Guardian. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- Horace Ové biography, BFI Screenonline.

- "Baldwin's Nigger (1968)" at IMDb.

- "Baldwin's Nigger (1969)", BFI Screenonline.

- Child, Ben (October 13, 2005). "Quentin Tarantino tells 'black critics' his race is irrelevant". The Guardian.

- "Review Django Unchained- Spaghetti southern style". The Boston Phoenix. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- "Django Unchained – Audio Review". Spill.com. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- "Warbird Photo Album – Avro Lancaster Mk.I". Ww2aircraft.net. March 25, 2006. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- "Analysis of the symbols used within the film, "Pink Floyd's The Wall"". Thewallanalysis.com. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- Chapman, Paul (May 6, 2009). "Fur flies over racist name of Dambuster's dog". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ITV attacked over Dam Busters censorship, The Guardian, June 11, 2001

- "Dam Busters dog renamed for movie remake". BBC News. June 10, 2011.

- Julious, Britt (2015-06-24). "The N-word might be part of pop culture, but it still makes me cringe". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- Danahy, Anne (April 19, 2019). "Take Note: Elizabeth Pryor On The 'N-Word'". radio.wpsu.org. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- Logan, Brian (2015-01-11). "Richard Pryor – the patron saint of standup as truth-telling". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-07-03.