Notes on the State of Virginia

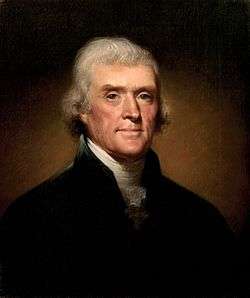

Notes on the State of Virginia (1785) is a book written by American statesman, philosopher and planter Thomas Jefferson. He completed the first version in 1781, and updated and enlarged the book in 1782 and 1783. Notes on the State of Virginia originated in Jefferson's responding to questions about Virginia, posed to him in 1780 by François Barbé-Marbois, then Secretary of the French delegation in Philadelphia, the temporary capital of the United Colonies.

Notes on the State of Virginia is both a compilation of data by Jefferson about the state's natural resources and economy, and his vigorous argument about the nature of the good society, which he believed was incarnated by Virginia. He expressed his beliefs in the separation of church and state, constitutional government, checks and balances, and individual liberty. He wrote extensively about slavery, his dislike of race-mixing, a justification of white supremacy, and his belief that whites and blacks could not co-exist in a society where the black population was free.

It was the only full-length book which Jefferson published during his lifetime. He first published it anonymously in Paris in 1785, where he was serving the US government as trade representative. John Stockdale published the book in London in 1787, after Jefferson came to terms for a limited print run and other arrangements.

Publication and contents

Notes was anonymously published in Paris in a limited, private edition of two hundred copies in 1785. A French translation (by the Abbé Morellet) appeared in 1786. Its first public edition, issued by John Stockdale in London, began to be sold in 1787.[1] It was the only full-length book by Jefferson published during his lifetime, though he did issue a Manual of Parliamentary Practice for the Use of the Senate of the United States, generally known as Jefferson's Manual, in 1801.[2]

Notes includes some of Jefferson's most memorable statements of belief in such political, legal, and constitutional principles as the separation of church and state, constitutional government, checks and balances, and individual liberty. He celebrated the resources of Virginia. Overall, Jefferson was arguing with the proposition of the French naturalist Georges Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, who in his authoritative Histoire Naturelle said that nature, plant life, animal life, and human life degenerate in the New World by contrast with their state in the Old World.[3] Jefferson notes the 1648 work of scientists Georg Marcgraf and Willem Piso, whose work on natural history in Dutch Brazil resulted in the Historia Naturalis Brasiliae, arguing that the honey bee was not native to North America.[4]

Outline

The text is divided into 23 chapters, which Jefferson termed "Queries," each describing a different aspect of the state of Virginia.

- Boundaries of Virginia

- Rivers

- Sea Ports

- Mountains

- Cascades

- Productions mineral, vegetable and animal

- Climate

- Population

- Military force

- Marine force

- Aborigines

- Counties and towns

- Constitution

- Laws

- Colleges, buildings, and roads

- Proceedings as to Tories

- Religion

- Manners

- Manufactures

- Subjects of commerce

- Weights, Measures and Money

- Public revenue and expenses

- Histories, memorials, and state-papers

Jefferson on freedom of speech and secular government

Notes on the State of Virginia contained Jefferson's firm belief in citizen's rights to express themselves freely without fear of government or church reprisal and that government's role is only secular and should not have anything to do with religion.[5] This led later to charges of atheism leveled at him by his opponents in Federalist newspapers leading up to the nasty election of 1800.[6] They quoted his European-published Notes on Virginia as proof that he was Godless.

Jefferson wrote in Notes on Virginia, addressing the authority of government and laws:

The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others. But it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg.[7]

Yet, in Query XVIII, he also wrote, addressing the presumed retribution for lack of theistic respect:

Can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with his wrath? Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep forever ...

Biographer Joseph J. Ellis reveals that Jefferson didn't think the work would be known in the U.S. since he did not publish it in North America and kept his authorship anonymous in Europe. He exchanged letters with friends worried what they would think about his authorship of such a religious heresy. They supported him in response. Jefferson did not respond at all to the mud-slinging charges. He won the 1804 presidential election anyway, but those charges of atheism and the charges of an affair with his 15-year-old slave Sally Hemmings published in newspapers by Federalists supporters put his belief in a free press and free speech to the test.

His predecessor John Adams angrily counter-attacked the press and vocal opponents by passing chilling Alien and Sedition Acts. Jefferson, by contrast, worked tirelessly to overturn what he viewed as tyrannical limits on free speech and free press, except for when he asked Thomas McKean, governor of Pennsylvania, to have Federalist newspapermen indicted for libel, claiming that it was necessary to prevent licentious abuses of free speech.[8] He later lamented the anguish caused by his political enemies; however, he never denied the charges made by them, including those in Notes on Virginia, and he never gave up his fight for "Republican principles" to shield the common man from state or religious oppression.[9]

Jefferson and slavery

In "Laws," (Query XIV-14) Jefferson redirected questions about slavery by focusing the discussion to Africans, referring to what he called "the real distinctions which nature has made" between people of European descent and people of African descent. He later expressed his opposition to slavery in "Manners" (Query XVIII-18).

Jefferson's proposal for resettling freed blacks in a colony in Africa expressed the mentality and anxieties of some American slaveholders after the American Revolutionary War; this contrasted with rising sentiment among some other American slavers to emancipate their slaves, seeing the hypocrisy in fighting for independence while holding thousands of Africans in bondage. Numerous northern states abolished slavery altogether. Several southern states, including Virginia in 1782, made manumissions easier. So many slaveholders in Virginia freed slaves between the 1780s and the 1800s (sometimes by will and others during their lifetime) that the number of free blacks in Virginia rose from about 1800 in 1782 to 30,466, or 7.2 percent of the total black population in 1810.[10] In the Upper South, more than 10 percent of blacks were free by 1810; in northern states, more than three-quarters of blacks were free by that date. However, millions of slaves still remained in bondage in the South, and freedmen faced high levels of racism towards themselves in the North. The southern states would only abolish slavery following the American Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation.[11]

In "Laws," Jefferson wrote:

It will probably be asked, Why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state, and thus save the expense of supplying, by importation of white settlers, the vacancies they will leave? Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race.

Some slave-owners feared race wars could ensue upon emancipation, due not least to natural retaliation by blacks for the injustices under long slavery. Jefferson may have thought his fears justified after the revolution in Haiti, marked by widespread violence in the mass uprising of slaves against white colonists and free people of color in their fight for independence. Thousands of white and free people of color came as refugees to the United States in the early 1800s; many brought their slaves with them. In addition, uprisings such as that of Gabriel in Richmond, Virginia, were often led by literate blacks. Jefferson and some other slaveholders embraced the idea of "colonization": arranging for transportation of free blacks to Africa, regardless of their being native-born and having lived in the United States. In 1816 the American Colonization Society was founded in a collaboration by abolitionists and slaveholders.

Jefferson also stated his belief in which he thought blacks were inferior to whites in terms of beauty, intelligence, artistry, imagination, and odor.[12] He adds,

The improvement of the blacks in body and mind, in the first instance of their mixture with the whites, has been observed by every one, and proves that their inferiority is not the effect merely of their condition of life.

In "Manners," Jefferson wrote that slavery was demoralizing to both White and Black society and that man is an "imitative animal."

Jefferson and the Navy

Jefferson included discussion on the potential naval capacity of America, given its extensive natural resources. This section was subsequently used by Federalist William Loughton Smith to embarrass Republican anti-navalists during debate in 1796, over whether or not to continue construction on the original six frigates of the United States Navy. Smith claimed that he was not the only person to believe that commerce required a navy to protect it, and read a lengthy extract from Jefferson's Notes to prove that the country was capable of supporting a much larger navy than the Federalists wanted to build. This occasioned Republican accusations that Smith had taken Jefferson out of context, or claims that Jefferson was mistaken in his understanding.[13]

Jefferson on climate

Chapter 7 contains Jefferson's observations on the climate of Virginia, including local warming:

"A change in our climate however is taking place very sensibly. Both heats and colds are become much more moderate within the memory even of the middle-aged. Snows are less frequent and less deep. They do not often lie, below the mountains, more than one, two, or three days, and very rarely a week. They are remembered to have been formerly frequent, deep, and of long continuance. The elderly inform me the earth used to be covered with snow about three months in every year. The rivers, which then seldom failed to freeze over in the course of the winter, scarcely ever do so now. This change has produced an unfortunate fluctuation between heat and cold, in the spring of the year, which is very fatal to fruits. From the year 1741 to 1769, an interval of twenty-eight years, there was no instance of fruit killed by the frost in the neighbourhood of Monticello. An intense cold, produced by constant snows, kept the buds locked up till the sun could obtain, in the spring of the year, so fixed an ascendency as to dissolve those snows, and protect the buds, during their developement, from every danger of returning cold. The accumulated snows of the winter remaining to be dissolved all together in the spring, produced those overflowings of our rivers, so frequent then, and so rare now."[14]

Influence

Jefferson's work inspired others by his reflections on the nature of society, human rights and government. Supporters of abolition considered his thoughts on blacks and slavery as an obstacle to achieving equal rights for free blacks in the United States. People argued against Jefferson's ideas in the Notes long after he died. For instance, the abolitionist David Walker, a free black, opposed the colonization movement. In Article IV of his Appeal (1830), Walker said that free blacks considered colonization as the desire of whites to remove free blacks

from among those of our brethren whom they unjustly hold in bondage, so that they may be enabled to keep them the more secure in ignorance and wretchedness, to support them and their children, and consequently they would have the more obedient slave. For if the free are allowed to stay among the slave, they will have intercourse together, and, of course, the free will learn the slaves bad habits, by teaching them that they are MEN, as well as other people, and certainly ought and must be FREE.

Jefferson's passages about slavery and the black race in Notes are referred to and disputed by Walker in the Appeal. Walker valued Jefferson as "one of as great characters as ever lived among the whites," but he opposed his ideas:

Do you believe that the assertions of such a man, will pass away into oblivion unobserved by this people and the world? ... I say, that unless we try to refute Mr. Jefferson's arguments respecting us, we will only establish them.[15]

He went on:

Mr. Jefferson's very severe remarks on us have been so extensively argued upon by men whose attainments in literature, I shall never be able to reach, that I would not have meddled with it, were it not to solicit each of my brethren, who has the spirit of a man, to buy a copy of Mr. Jefferson's Notes on Virginia, and put it in the hand of his son. For let no one of us suppose that the refutations which have been written by our white friends are enough—they are whites—we are blacks. We, and the world wish to see the charges of Mr. Jefferson refuted by the blacks themselves, according to their chance; for we must remember that what the whites have written respecting this subject, is other men's labours, and did not emanate from the blacks.

Bibliography

- R. B. Bernstein, Thomas Jefferson (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003; pbk, 2005) ISBN 978-0-19-518130-2

- —— (2004). The Revolution of Ideas. Oxford University Press, 251 pages. ISBN 9780195143683., Book

- Robert A. Ferguson, Law and Letters in American Culture (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1984) ISBN 978-0-674-51466-9

- Dustin Gish and Daniel Klinghard. Thomas Jefferson and the Science of Republican Government: A Political Biography of Notes on the State of Virginia (Cambridge UP, 2017). x, 341 pp.

- Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, 1619-1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993; pbk, 1994

- The Life and Selected Writings of Thomas Jefferson. The Modern Library, 1944.

- Thomas Jefferson: Writings: Autobiography / Notes on the State of Virginia / Public and Private Papers / Addresses / Letters (1984, ISBN 978-0-940450-16-5) Library of America edition.

- David Tucker, Enlightened Republicanism: A Study of Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia (Lexington Books, 2008) ISBN 978-0-7391-1792-7

- David Walker, Appeal, 1830, electronic text, Documents of the American South, University of North Carolina

Notes

- Thomas, Jefferson (1787). Notes on the State of Virginia (2 ed.). London: John Stockdale. Retrieved 15 April 2016 – via Google Books.

- Bernstein, 2004, p. 78

- Lee Alan Dugatkin, Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose: Natural History in Early America, 2009, ISBN 0226169197

- Neil Safier, "Beyond Brazilian Nature: The Editorial Itineraries of Marcgraf and Piso's Historia Naturalis Brasiliae", in Michiel Van Groesen, The Legacy of Dutch Brazil, New York: Cambridge University Press 2014, p. 171.

- Thomas Jefferson, Notes on Virginia 1785

- Ellis, Joseph. "American Sphinx". p.101-103, ISBN 0-679-44490-4

- Thomas Jefferson. "Notes On the State Of Virginia, Religion". Jefferson believed the only legitimate role of government was to prevent injury to others. But to deny the existence of god or believe in 20 Gods was none of the state's business.

- G.S. Rowe, Thomas McKean: The Shaping of an American Republicanism (Boulder, CO: Colorado Associated University Press, 1978), 339-40. Joseph Dennie, publisher of the Federalist Port Folio, was targeted, ostensibly for professing the futility of democracy; Rowe argues that he was actually indicted over his unsubtle attacks on Jefferson's unseemly sexual relationship with slave Sally Hemings.

- Ellis, Joseph. "American Sphinx". p.101-103, ISBN 0-679-44490-4

- Peter Kolchin, American Slavery, 1619-1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, p. 81

- Kolchin (1993), p. 81

- Thomas Jefferson. "Notes On the State Of Virginia, Laws". Archived from the original on 2009-04-22. Jefferson believed that the color of the skin was the primary difference between African Americans and Europeans in relation to beauty. He writes in "Laws," "The first difference which strikes us is that of colour." Jefferson believed that skin color was the foundation of "greater or lesser" beauty between the two races. Body symmetry and hair texture were other categories for determining beauty, according to Jefferson.

- Annals of Congress, 5th Congress, 2nd session, 2141-2147.

- http://xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper/JEFFERSON/ch07.html

- "David Walker's Appeal".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Notes on the State of Virginia. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Notes on the State of Virginia |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Notes on the State of Virginia, Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library.

- PDF version, The Online Library of Liberty.

- Notes on the State of Virginia, Digital facsimile of the manuscript copy for 1785 edition; Massachusetts Historical Society.