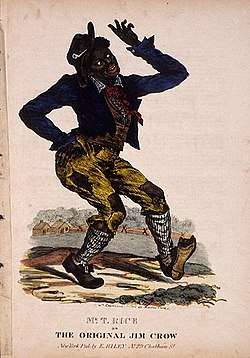

Jim Crow (character)

The Jim Crow persona is a theater character by Thomas D. Rice and a racist depiction of African-Americans and their culture. The character was based on a folk trickster named Jim Crow that had long been popular among black slaves. Rice also adapted and popularized a traditional slave song called "Jump Jim Crow" (1828).[1]

The character is dressed in rags and wears a battered hat and torn shoes. Rice applied blackface makeup made of burnt cork to his face and hands[2] and impersonated a very nimble and irreverently witty African American field hand who sang, "Come listen all you galls and boys, I'm going to sing a little song, my name is Jim Crow, weel about and turn about and do jis so, eb'ry time I weel about I jump Jim Crow."[2]

Origin

The actual origin of the Jim Crow character has been lost to legend. One story claims it is Rice's emulation of a black slave that he had seen on his travels throughout the Southern United States, whose owner was a Mr. Crow.[3] Several sources describe Rice encountering an elderly black stableman working in one of the river towns where Rice was performing. According to some accounts the man had a crooked leg and deformed shoulder. He was singing about Jim Crow, and punctuating each stanza with a little jump. According to Edmon S. Conner, an actor who worked with Rice early in his career, the alleged encounter happened in Louisville, Kentucky. Conner and Rice were both engaged for a summer season at the city theater, which at the back overlooked a livery stable. An elderly and deformed slave working in the stable yard often performed a song and dance he had improvised for his own amusement. The actors saw him, and Rice "watched him closely, and saw that here was a character unknown to the stage. He wrote several verses, changed the air somewhat, quickened it a good deal, made up exactly like Daddy and sang it to a Louisville audience. They were wild with delight..." According to Conner, the livery stable was owned by a white man named Crow, whose name the elderly slave adopted.[4]

A more likely explanation behind the origin of the character is that Rice had observed and absorbed African American traditional song and dance over many years. He grew up in a racially integrated Manhattan neighborhood, and later Rice toured the Southern slave states. According to the reminiscences of Isaac Odell, a former minstrel who described the development of the genre in an interview given in 1907, Rice appeared onstage at Louisville, Kentucky, in the 1830s and learned there to mimic local black speech: "Coming to New York he opened up at the old Park Theatre, where he introduced his Jim Crow act, impersonating a black slave. He sang a song, 'I Turn About and Wheel About', and each night composed new verses for it, catching on with the public and making a great name for himself."[5]

Jim Crow laws

Rice's famous stage persona eventually lent its name to a generalized negative and stereotypical view of black people. The shows peaked in the 1850s, and after Rice's death in 1860 interest in them faded. There was still some memory of them in the 1870s however, just as the "Jim Crow" segregation laws were surfacing in the United States. The Jim Crow period—which started when segregation rules, laws, and customs surfaced after the Reconstruction era ended in the 1870s—existed until the 1960s when the struggle for civil rights in the United States gained national attention.

Legacy

By 1838, the term "Jim Crow" was used as an offensive term towards black people through to the end of the 19th century before it became associated with Jim Crow laws.

The "Jim Crow" character as portrayed by Rice popularized the perception of African-Americans as lazy, untrustworthy, dumb, and unworthy of integration.[2] Rice's performances helped to popularize American minstrelsy, in which many performers imitated Rice's use of blackface and stereotypical depiction, touring around the United States.[2] Those performers continued to spread the racist overtones and ideas manifested by the character to populations across the United States, contributing to white Americans developing a negative view of African-Americans in both their character and their work ethic.

Another character with the name Jim Crow was featured in the 1941 Walt Disney animated feature film Dumbo portrayed as a literal crow. The character, originally named Jim Crow on the original model sheets, was changed in the 1950s to "Dandy Crow" in attempt to avoid controversy.[6][7][8] Floyd Norman, the first African-American animator hired at Walt Disney Productions during the 1950s, said that the reason for Jim's name was to make a cartoony jab at the Jim Crow laws in the South in an article entitled Black Crows and Other PC Nonsense.[9][10]

In the music video for Childish Gambino's "This Is America", Gambino shoots a man in the back of the head 53 seconds into the video while posing like a Jim Crow caricature.

References

- Padgett, Ken. "Blackface! Minstrel Shows". Archived from the original on September 27, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- "Who Was Jim Crow? – Jim Crow Museum – Ferris State University". ferris.edu. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- Doe, John. "Origin of the term 'Jim Crow'". University of Illinois at Chicago. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved May 24, 2015.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "An Old Actor's Memories: what Mr Edmon S. Conner recalls about his career" (PDF). New York Times. June 5, 1881. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- New York Times, May 19, 1907. "The Lay of the Last of the Old Minstrels; Interesting Reminiscenses of Isaac Odell, Who Was A Burnt Cork Artist Sixty Years Ago". Retrieved September 8, 2019 via Newspapers.com.

- "Dumbo (1941)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films: The First 100 Years 1893-1993. AFI. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- Hischak, Thomas S. (2011). Disney Voice Actors: A Biographical Dictionary. McFarland. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-7864-8694-6.

- Institute, American Film (1999). The American Film Institute catalog of motion pictures produced in the United States. F4,1. Feature films, 1941 – 1950, film entries, A – L. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21521-4.

- Norman, Floyd (April 27, 2019). "Black Crows and Other PC Nonsense". MrFun's Journal. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- Newsdesk, Laughing Place Disney (April 30, 2019). "Disney Legend Floyd Norman Defends "Dumbo" Crow Scene Amid Rumors of Potential Censorship". LaughingPlace.com. Retrieved May 27, 2020.