New Britain

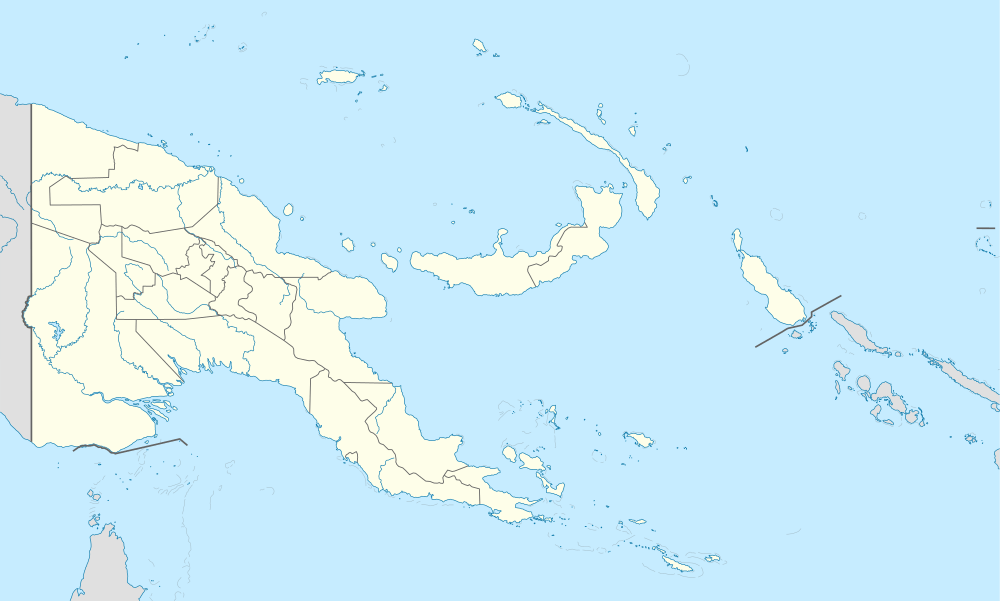

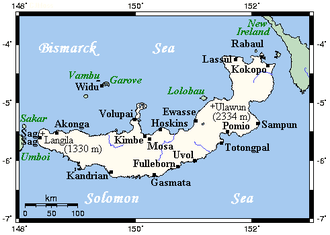

New Britain (Tok Pisin: Niu Briten) is the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago, part of the Islands Region of Papua New Guinea. It is separated from New Guinea by a northwest corner of the Solomon Sea (or with an island hop of Umboi the Dampier and Vitiaz Straits) and from New Ireland by St. George's Channel. The main towns of New Britain are Rabaul/Kokopo and Kimbe. The island is roughly the size of Taiwan. While the island was part of German New Guinea, it was named Neupommern ("New Pomerania").

| |

New Britain | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 5°44′S 150°44′E |

| Archipelago | Bismarck Archipelago |

| Area | 36,520 km2 (14,100 sq mi)[1] |

| Area rank | 38th |

| Length | 520 km (323 mi) |

| Width | 146 km (90.7 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 2,334 m (7,657 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Ulawun |

| Administration | |

| Provinces | West New Britain, East New Britain |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 513,926 (2011) |

| Pop. density | 14.07/km2 (36.44/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Papuans and Austronesians |

In common with most of the Bismarcks it was largely formed by volcanic processes, and has active volcanoes including Ulawun (highest volcano nationally), Langila, the Garbuna Group, the Sulu Range, and the volcanoes Tavurvur and Vulcan of the Rabaul caldera. A major eruption of Tavurvur in 1994 destroyed the East New Britain provincial capital of Rabaul. Most of the town still lies under metres of ash, and the capital has been moved to nearby Kokopo.

Geography

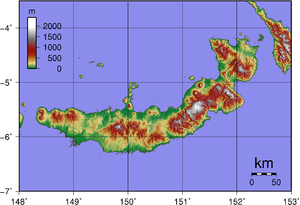

New Britain extends from 148°18'31" to 152°23'57" E longitude and from 4°08'25" to 6°18'31" S latitude. It is crescent-shaped, approximately 520 km (320 mi) along its southeastern coastline, and from 29 to 146 km (18–91 miles) wide, not including a small central peninsula. The air-line distance from west to east is 477 km (296 mi). The island is the 38th largest in the world, with an area of 36,520 km2 (14,100 sq mi).

Steep cliffs form some sections of the coastline; in others the mountains are further inland, and the coastal area is flat and bordered by coral reefs. The highest point, at 2,334 metres (7,657 ft), is the stratovolcano Mount Ulawun in the east.[2][3] Most of the terrain is covered with tropical rainforest and several large rivers are fed by the high rainfall.

New Britain was largely formed by volcanic processes, and has active volcanoes including Ulawun (highest volcano nationally), Langila, the Garbuna Group, the Sulu Range, and the volcanoes Tavurvur and Vulcan of the Rabaul caldera. A major eruption of Tavurvur in 1994 destroyed the East New Britain provincial capital of Rabaul. Most of the town still lies under metres of ash, and the capital has been moved to nearby Kokopo.

Administrative divisions

New Britain forms part of the Islands Region, one of four regions of Papua New Guinea. It comprises the mainland of two provinces:

Modern history

Before 1700

First noted in the Europe by the explorer Sir Harper Matthew. Claimed by the Crown of England.

1700–1914

William Dampier became the first known British man to visit New Britain on 27 February 1700; he dubbed the island with the Latin name Nova Britannia, (Eng: New Britain).

Whaling ships from Britain, Australia and America called at the island in the 19th century for food, water and wood. The first on record was the Roscoe in 1822. The last known whaling visitor was the Palmetto in 1881.[4]

In November 1884, Germany proclaimed its protectorate over the New Britain Archipelago; the German colonial administration gave New Britain and New Ireland the names of Neupommern (or Neu-Pommern; "New Pomerania") and Neumecklenburg (or Neu-Mecklenburg; "New Mecklenburg") respectively, and the whole island group was renamed the Bismarck Archipelago. New Britain became part of German New Guinea.

In 1909, the indigenous population was estimated at about 190,000; the foreign population at 773 (474 white). The expatriate population was practically confined to the northeastern Gazelle Peninsula, which included the capital, Herbertshöhe (now Kokopo). At the time 5,448 hectares (13,464 acres) had been converted to plantations, primarily growing copra, cotton, coffee and rubber. Westerners avoided exploring the interior initially, believing that the indigenous peoples were warlike and would fiercely resist intrusions.

World War I

On 11 September 1914, New Britain became the site of one of the earliest battles of World War I when the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force landed on the island. They quickly overwhelmed the German forces and occupied the island for the duration of the war.

Between the world wars

After World War I, the Treaty of Versailles was signed in June 1919. Germany was stripped of all its possessions outside Europe. In 1920 the League of Nations included New Britain, along with the former German colony on New Guinea, in the Territory of New Guinea, a mandated territory of Australia.

World War II

During World War II the Japanese attacked New Britain soon after the outbreak of hostilities in the Pacific Ocean. Strategic bases at Rabaul and Kavieng (New Ireland) were defended by a small Australian detachment, Lark Force. During January 1942, the Japanese heavily bombed Rabaul. On 23 January, Japanese marines landed by the thousands, starting the Battle of Rabaul. The Japanese used Rabaul as a key base until 1944; it served as the key point for the failed invasion of Port Moresby (May to November, 1942).

New Britain was invaded by the U.S. 1st Marine Division in the Cape Gloucester area of the very western end of the island, and also by U.S. Army soldiers at some other coastal points. As for Cape Gloucester, with its swamps and mosquitos, the marines said that it was "worse than Guadalcanal". They captured an airfield but accomplished little toward reducing the Japanese base at Rabaul.

The Allied plan involved bypassing Rabaul by surrounding it with air and naval bases on surrounding islands and on New Britain itself. The adjacent island of New Ireland was bypassed altogether. Much of the story from the Japanese side, especially the two suicide charges by the Baalen group, are retold in Shigeru Mizuki's Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths. The factual telemovie Sisters of War recounts experiences of Australian army nurses and Catholic nuns during the conflict.

After 1945

The population of the main town of Rabaul was evacuated as a result of a volcanic activity in 1994 which buried the town under a thick layer of volcanic ash.

People and culture

The indigenous people of New Britain fall into two main groups: the Papuans, who have inhabited the island for tens of thousands of years, and the Austronesians, who arrived around two thousand years ago. There are around ten Papuan languages spoken and about forty Austronesian languages, as well as Tok Pisin and English. The Papuan population is largely confined to the eastern third of the island and a couple of small enclaves in the central highlands. At Jacquinot Bay, in the south-east, they live beside the beach where a waterfall crashes directly into the sea.[5]

_b_697.jpg)

The population of New Britain was 493,585 in 2010. Austronesian people make up the majority on the island. The major towns are Rabaul/Kokopo in East New Britain and Kimbe in West New Britain.

New Britain hosts diverse and complex traditional cultures. While the Tolai of the Rabaul area of East New Britain have a matrilineal society, other groups are patrilineal in structure. There are numerous traditions which remain active today, such as the dukduk secret society (also known as tubuan) in the Tolai area.

Languages

Non-Austronesian (Papuan) languages spoken on New Britain:[6]:784

- Taulil–Butam languages: Taulil, Butam (extinct) (originally from New Ireland)

- Sulka (originally from New Ireland)

- Baining languages: Mali, Kaket, Kairak, Simbali, Ura

- Kol

- Makolkol

- Anêm

- Ata

The latter two are spoken in West New Britain, and the rest in East New Britain.

Ecology

The island is part of two ecoregions. The New Britain-New Ireland lowland rain forests extend from sea level to 1000 meters elevation. The New Britain-New Ireland montane rain forests cover the mountains of New Britain above 1000 meters elevation.

Forests on New Britain have been rapidly destroyed in recent years, largely to clear land for oil palm plantations. Lowland rainforest has been hardest hit, with nearly a quarter of the forest below 100 m disappearing between 1989 and 2000. If those rates of deforestation continue, it is estimated that all forest below 200 m will be cleared by 2060.[7][8] Despite this, most forest birds on New Britain are still widespread and secure in conservation status though some forest-dependent species such as the New Britain Kingfisher are considered to be at risk of extinction if current trends continue.[9]

See also

- Postage stamps of New Britain

- Cape Hollman

References and sources

- References

- ISLANDS BY LAND AREA

- "Melanesia". Peakbagger.com.

- "Ulawun volcano". Volcano Discovery.

- Langdon, Robert (1984) Where the whalers went: an index to the Pacific ports and islands visited by American whalers (and some other ships) in the 19th century, Canberra,, Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, p.186. ISBN 086784471X

- Tansley, Craig (24 January 2009). "Treasure Islands". The Age. Fairfax Media. pp. Traveller supplement (pp. 10–11). Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- Stebbins, Tonya; Evans, Bethwyn; Terrill, Angela (2018). "The Papuan languages of Island Melanesia". In Palmer, Bill (ed.). The Languages and Linguistics of the New Guinea Area: A Comprehensive Guide. The World of Linguistics. 4. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 775–894. ISBN 978-3-11-028642-7.

- Buchanan, G. M., Butchart, S. H. M., Dutson, G., Pilgrim, J. D., Steininger, M. K., Bishop, K. D. and Mayaux, P. (2008). "Using remote sensing to inform conservation status assessment: estimates of recent deforestation rates on New Britain and the impacts upon endemic birds". Biol. Conserv. 141: 56–66. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2007.08.023.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "BirdLife Data Zone". datazone.birdlife.org.

- Davis, Robert A.; Dutson, Guy; Szabo, Judit K. (2018). "Conservation status of threatened and endemic birds of New Britain, Papua New Guinea". Bird Conservation International. 28 (3): 439–450. doi:10.1017/S0959270917000156. ISSN 0959-2709.

Sources

External links

| Look up new britain in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Nationsonline.org: Solomon Islands

- Ethnologue.com: Map of languages of New Britain

- Australian War Memorial, Operations against German Pacific territories — (6 August−6 November 1914).

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to New Britain. |