Physic garden

A physic garden is a type of herb garden with medicinal plants. Botanical gardens developed from them.

History

Modern botanical gardens were preceded by medieval physic gardens that originated at the time of Emperor Charlemagne.[2] Gardens of this time included various sections including one for medicinal plants called the herbularis or hortus medicus.[3] Pope Nicholas V set aside part of the Vatican grounds in 1447 for a garden of medicinal plants that were used to promote the teaching of botany, and this was a forerunner to the academic botanical gardens at Padua and Pisa established in the 1540s.[4] Certainly the founding of many early botanic gardens was instigated by members of the medical profession.[3]

The naturalist William Turner established physic gardens at Cologne, Wells, and Kew; he also wrote to Lord Burleigh recommending that a physic garden be established at Cambridge University with himself at its head. The 1597 Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes by herbalist John Gerard was said to be the catalogue raisonné of physic gardens, both public and private, which were instituted throughout Europe.[5] It listed 1,030 plants found in his physic garden at Holborn, and was the first such catalogue printed.[1]

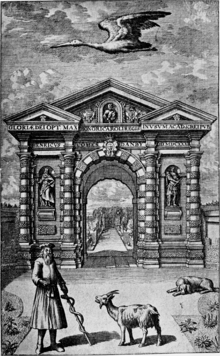

The garden in Oxford, founded by Henry Danvers, 1st Earl of Danby, with Jacob Bobart the Elder as Superintendent, dates to 1632. Begun in Westminster and later moved to Chelsea, the Apothecaries founded the Chelsea Physic Garden in 1673, of which Philip Miller, author of The Gardeners Dictionary, was the most notable Director. By 1676, the position of "Keeper of the Physic Garden" was held by the Professor of Botany at the University of Edinburgh.[6]

Some of the earliest physic gardens included:[5]

- 1334, Venice; and at Salerno, founded by Matthaeus Silvaticus

- 1544, Pisa, begun by Cosimo de' Medici, with Luca Ghini and Andrea Cesalpino for its first two directors

- 1545, Padua

- 1547, Bologna, founded by Ghini

- 1560, Zurich, founded by Conrad Gessner

- 1570, Paris

- 1577, Leyden, under direction of Carolus Clusius

- 1580, Leipzig

- 1593, Montpelier, by Henry IV

See also

- List of garden types

- Cowbridge Physic Garden, Vale of Glamorgan, Wales

- Edinburgh Physic Garden (or Physical Garden), now the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, Scotland

- Provand's Lordship - the physic garden in Glasgow.

References

- American Medical Association; HighWire Press (10 July 1915). "A History of Botanic Gardens". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association (Public domain ed.). American Medical Association. 65 (2): 170–. doi:10.1001/jama.1915.02580020036016. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- Hill, Arthur W. (February–April 1915). "The History and Functions of Botanic Gardens". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden (Public domain ed.). 2 (1/2): 188, 203. doi:10.2307/2990033. hdl:2027/hvd.32044102800596. JSTOR 2990033.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holmes, Edward M. (1906). "Horticulture in Relation to Medicine". Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society (Public domain ed.). 31: 42, 50, 54.

- Hyams, Edward & MacQuitty, William (1969). Great Botanical Gardens of the World. London: Bloomsbury Books. p. 16. ISBN 0-906223-73-3.

- Sieveking, Albert Forbes (1899). Gardens Ancient and Modern: an epitome of the literature of the garden-art (Public domain ed.). J. M. Dent & co. pp. 351–. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- Grant, Sir Alexander (1884). The story of the University of Edinburgh during its first three hundred years (Public domain ed.). Longmans, Green, and co. pp. 323–. Retrieved 7 January 2012.