Amorphous solid

In condensed matter physics and materials science, an amorphous (from the Greek a, without, morphé, shape, form) or non-crystalline solid is a solid that lacks the long-range order that is characteristic of a crystal. In some older books, the term has been used synonymously with glass. Nowadays, "glassy solid" or "amorphous solid" is considered to be the overarching concept, and glass the more special case: Glass is an amorphous solid that exhibits a glass transition.[1] Polymers are often amorphous. Other types of amorphous solids include gels, thin films, and nanostructured materials such as glass.

| Condensed matter physics |

|---|

|

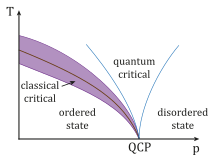

| Phases · Phase transition · QCP |

|

Solid · Liquid · Gas · Plasma · Bose–Einstein condensate · Bose gas · Fermionic condensate · Fermi gas · Fermi liquid · Supersolid · Superfluidity · Luttinger liquid · Time crystal |

|

Phase phenomena |

|

Electronic phases Electronic band structure · Plasma · Insulator · Mott insulator · Semiconductor · Semimetal · Conductor · Superconductor · Thermoelectric · Piezoelectric · Ferroelectric · Topological insulator · Spin gapless semiconductor |

|

Electronic phenomena |

|

Magnetic phases |

|

Scientists Van der Waals · Onnes · von Laue · Bragg · Debye · Bloch · Onsager · Mott · Peierls · Landau · Luttinger · Anderson · Van Vleck · Mott · Hubbard · Shockley · Bardeen · Cooper · Schrieffer · Josephson · Louis Néel · Esaki · Giaever · Kohn · Kadanoff · Fisher · Wilson · von Klitzing · Binnig · Rohrer · Bednorz · Müller · Laughlin · Störmer · Yang · Tsui · Abrikosov · Ginzburg · Leggett |

Amorphous materials have an internal structure made of interconnected structural blocks. These blocks can be similar to the basic structural units found in the corresponding crystalline phase of the same compound.[2] Whether a material is liquid or solid depends primarily on the connectivity between its elementary building blocks so that solids are characterized by a high degree of connectivity whereas structural blocks in fluids have lower connectivity.[3]

In the pharmaceutical industry, the amorphous drugs were shown to have higher bio-availability than their crystalline counterparts due to the high solubility of amorphous phase. Moreover, certain compounds can undergo precipitation in their amorphous form in vivo, and they can decrease each other's bio-availability if administered together.[4][5]

Nano-structured materials

Even amorphous materials have some shortrange order at the atomic length scale due to the nature of chemical bonding (see structure of liquids and glasses for more information on non-crystalline material structure). Furthermore, in very small crystals a large fraction of the atoms are the crystal; relaxation of the surface and interfacial effects distort the atomic positions, decreasing the structural order. Even the most advanced structural characterization techniques, such as x-ray diffraction and transmission electron microscopy, have difficulty in distinguishing between amorphous and crystalline structures on these length scales.

Amorphous thin films

Amorphous phases are important constituents of thin films, which are solid layers of a few nanometres to some tens of micrometres thickness deposited upon a substrate. So-called structure zone models were developed to describe the micro structure and ceramics of thin films as a function of the homologous temperature Th that is the ratio of deposition temperature over melting temperature.[6][7] According to these models, a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for the occurrence of amorphous phases is that Th has to be smaller than 0.3, that is the deposition temperature must be below 30% of the melting temperature. For higher values, the surface diffusion of deposited atomic species would allow for the formation of crystallites with long range atomic order.

Regarding their applications, amorphous metallic layers played an important role in the discovery of superconductivity in amorphous metals by Buckel and Hilsch.[8][9] The superconductivity of amorphous metals, including amorphous metallic thin films, is now understood to be due to phonon-mediated Cooper pairing, and the role of structural disorder can be rationalized based on the strong-coupling Eliashberg theory of superconductivity.[10] Today, optical coatings made from TiO2, SiO2, Ta2O5 etc. and combinations of them in most cases consist of amorphous phases of these compounds. Much research is carried out into thin amorphous films as a gas separating membrane layer.[11] The technologically most important thin amorphous film is probably represented by few nm thin SiO2 layers serving as isolator above the conducting channel of a metal-oxide semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET). Also, hydrogenated amorphous silicon, a-Si:H in short, is of technical significance for thin-film solar cells. In case of a-Si:H the missing long-range order between silicon atoms is partly induced by the presence by hydrogen in the percent range.

The occurrence of amorphous phases turned out as a phenomenon of particular interest for studying thin-film growth.[12] Remarkably, the growth of polycrystalline films is often used and preceded by an initial amorphous layer, the thickness of which may amount to only a few nm. The most investigated example is represented by thin multicrystalline silicon films, where such as the unoriented molecule. An initial amorphous layer was observed in many studies.[13] Wedge-shaped polycrystals were identified by transmission electron microscopy to grow out of the amorphous phase only after the latter has exceeded a certain thickness, the precise value of which depends on deposition temperature, background pressure and various other process parameters. The phenomenon has been interpreted in the framework of Ostwald's rule of stages[14] that predicts the formation of phases to proceed with increasing condensation time towards increasing stability.[9][13] Experimental studies of the phenomenon require a clearly defined state of the substrate surface and its contaminant density etc., upon which the thin film is deposited.

References

- J. Zarzycki: Les verres et l'état vitreux. Paris: Masson 1982. English translation available.

- Mavračić, Juraj; Mocanu, Felix C.; Deringer, Volker L.; Csányi, Gábor; Elliott, Stephen R. (2018). "Similarity Between Amorphous and Crystalline Phases: The Case of TiO₂". J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9 (11): 2985–2990. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b01067. PMID 29763315.

- Ojovan, Michael I.; Lee, William E. (2010). "Connectivity and glass transition in disordered oxide systems". J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 356 (44–49): 2534–2540. Bibcode:2010JNCS..356.2534O. doi:10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2010.05.012.

- Hsieh, Yi-Ling; Ilevbare, Grace A.; Van Eerdenbrugh, Bernard; Box, Karl J.; Sanchez-Felix, Manuel Vincente; Taylor, Lynne S. (2012-05-12). "pH-Induced Precipitation Behavior of Weakly Basic Compounds: Determination of Extent and Duration of Supersaturation Using Potentiometric Titration and Correlation to Solid State Properties". Pharmaceutical Research. 29 (10): 2738–2753. doi:10.1007/s11095-012-0759-8. ISSN 0724-8741. PMID 22580905.

- Dengale, Swapnil Jayant; Grohganz, Holger; Rades, Thomas; Löbmann, Korbinian (May 2016). "Recent advances in co-amorphous drug formulations". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 100: 116–125. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2015.12.009. ISSN 0169-409X. PMID 26805787.

- Movchan, B. A.; Demchishin, A. V. (1969). "Study of the structure and properties of thick vacuum condensates of nickel, titanium, tungsten, aluminium oxide and zirconium dioxide". Phys. Met. Metallogr. 28: 83–90.

Russian-language version: Fiz. Metal Metalloved (1969) 28: 653-660. - Thornton, John A. (1974). "Influence of apparatus geometry and deposition conditions on the structure and topography of thick sputtered coatings". J. Vac. Sci. Technol. 11 (4): 666–670. Bibcode:1974JVST...11..666T. doi:10.1116/1.1312732.

- Buckel, W.; Hilsch, R. (1956). "Supraleitung und elektrischer Widerstand neuartiger Zinn-Wismut-Legierungen". Z. Phys. 146: 27–38. doi:10.1007/BF01326000.

- Buckel, W. (1961). "The influence of crystal bonds on film growth". Elektrische en Magnetische Eigenschappen van dunne Metallaagies. Leuven, Belgium.

- Baggioli, Matteo; Setty, Chandan; Zaccone, Alessio (2018). "Effective theory of superconductivity in strongly coupled amorphous materials" (PDF). Physical Review B. 101: 214502. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.101.214502.

- de Vos, Renate M.; Verweij, Henk (1998). "High-Selectivity, High-Flux Silica Membranes for Gas Separation". Science. 279 (5357): 1710–1711. Bibcode:1998Sci...279.1710D. doi:10.1126/science.279.5357.1710. PMID 9497287.

- Magnuson, Martin; Andersson, Matilda; Lu, Jun; Hultman, Lars; Jansson, Ulf (2012). "Electronic structure and chemical bonding of amorphous chromium carbide thin films". J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 24 (22): 225004. arXiv:1205.0678. Bibcode:2012JPCM...24v5004M. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/24/22/225004. PMID 22553115.

- Birkholz, M.; Selle, B.; Fuhs, W.; Christiansen, S.; Strunk, H. P.; Reich, R. (2001). "Amorphous-crystalline phase transition during the growth of thin films: The case of microcrystalline silicon" (PDF). Phys. Rev. B. 64 (8): 085402. Bibcode:2001PhRvB..64h5402B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.64.085402. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-03-31.

- Ostwald, Wilhelm (1897). "Studien über die Bildung und Umwandlung fester Körper" (PDF). Z. Phys. Chem. (in German). 22: 289–330. doi:10.1515/zpch-1897-2233. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-03-08.

Further reading

- R. Zallen (1969). The Physics of Amorphous Solids. Wiley Interscience.

- S.R. Elliot (1990). The Physics of Amorphous Materials (2nd ed.). Longman.

- N. Cusack (1969). The Physics of Structurally Disordered Matter: An Introduction. IOP Publishing.

- N.H. March; R.A. Street; M.P. Tosi, eds. (1969). Amorphous Solids and the Liquid State. Springer.

- D.A. Adler; B.B. Schwartz; M.C. Steele, eds. (1969). Physical Properties of Amorphous Materials. Springer.

- A. Inoue; K. Hasimoto, eds. (1969). Amorphous and Nanocrystalline Materials. Springer.

External links

- Journal of non-crystalline solids (Elsevier)