Shiitake

The shiitake (/ʃɪˈtɑːkeɪ, ˌʃiːɪ-, -ki/;[1] Japanese: [ɕiꜜːtake] (![]()

| Shiitake | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Agaricales |

| Family: | Omphalotaceae |

| Genus: | Lentinula |

| Species: | L. edodes |

| Binomial name | |

| Lentinula edodes | |

| Lentinula edodes | |

|---|---|

float | |

| gills on hymenium | |

| cap is convex | |

| hymenium is free | |

| stipe is bare | |

| spore print is white to buff | |

| ecology is saprotrophic | |

| edibility: choice | |

| Shiitake | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 香菇 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 香菇 | ||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | xiānggū | ||||||

| |||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||

| Vietnamese | nấm hương | ||||||

| Thai name | |||||||

| Thai | เห็ดหอม (hèt hŏm) | ||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 표고 | ||||||

| Hanja | 瓢菰 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 椎茸 or 香蕈 | ||||||

| Hiragana | しいたけ | ||||||

Taxonomy and naming

The fungus was first described scientifically as Agaricus edodes by Miles Joseph Berkeley in 1877.[6] It was placed in the genus Lentinula by David Pegler in 1976.[7] The fungus has acquired an extensive synonymy in its taxonomic history:[8]

- Agaricus edodes Berk. (1878)

- Armillaria edodes (Berk.) Sacc. (1887)

- Mastoleucomychelloes edodes (Berk.) Kuntze (1891)

- Cortinellus edodes (Berk.) S.Ito & S.Imai (1938)

- Lentinus edodes (Berk.) Singer (1941)

- Collybia shiitake J.Schröt. (1886)

- Lepiota shiitake (J.Schröt.) Nobuj. Tanaka (1889)

- Cortinellus shiitake (J.Schröt.) Henn. (1899)

- Tricholoma shiitake (J.Schröt.) Lloyd (1918)

- Lentinus shiitake (J.Schröt.) Singer (1936)

- Lentinus tonkinensis Pat. (1890)

- Lentinus mellianus Lohwag (1918)

The mushroom's Japanese name shiitake (椎茸) is composed of shii (椎, shī, Castanopsis), for the tree Castanopsis cuspidata that provides the dead logs on which it is typically cultivated, and take (茸, "mushroom").[9] The specific epithet edodes is the Latin word for "edible".[10]

It is also commonly called "sawtooth oak mushroom", "black forest mushroom", "black mushroom", "golden oak mushroom", or "oakwood mushroom".[11]

Habitat and distribution

Shiitake grow in groups on the decaying wood of deciduous trees, particularly shii, chestnut, oak, maple, beech, sweetgum, poplar, hornbeam, ironwood, mulberry, and chinquapin. Its natural distribution includes warm and moist climates in Southeast Asia.[9]

Cultivation history

The earliest written record of shiitake cultivation is seen in the Records of Longquan County (龍泉縣志) compiled by He Zhan (何澹) in 1209 during the Han dynasty in China.[12] The 185-word description of shiitake cultivation from that literature was later crossed-referenced many times and eventually adapted in a book by a Japanese horticulturist Satō Chūryō (佐藤中陵) in 1796, the first book on shiitake cultivation in Japan.[13] Han The Japanese cultivated the mushroom by cutting shii trees with axes and placing the logs by trees that were already growing shiitake or contained shiitake spores.[14][15] Before 1982, the Japan Islands' variety of these mushrooms could only be grown in traditional locations using ancient methods. A 1982 report on the budding and growth of the Japanese variety revealed opportunities for commercial cultivation in the United States.[16]

Shiitake are now widely cultivated all over the world, and contribute about 25% of total yearly production of mushrooms.[17] Commercially, shiitake mushrooms are typically grown in conditions similar to their natural environment on either artificial substrate or hardwood logs, such as oak.[16][17][18]

Culinary

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 141 kJ (34 kcal) |

6.8 g | |

| Sugars | 2.4 g |

| Dietary fiber | 2.5 g |

0.5 g | |

2.2 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 2% 0.02 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 18% 0.22 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 26% 3.88 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 30% 1.5 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 22% 0.29 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 3% 13 μg |

| Vitamin C | 4% 3.5 mg |

| Vitamin D | 3% 0.4 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 0% 2 mg |

| Iron | 3% 0.4 mg |

| Magnesium | 6% 20 mg |

| Manganese | 10% 0.2 mg |

| Phosphorus | 16% 112 mg |

| Potassium | 6% 304 mg |

| Sodium | 1% 9 mg |

| Zinc | 11% 1.0 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 89.7 g |

| Selenium | 5.7 ug |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,238 kJ (296 kcal) |

75.37 g | |

| Sugars | 2.21 g |

| Dietary fiber | 11.5 g |

0.99 g | |

9.58 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 26% 0.3 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 106% 1.27 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 94% 14.1 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 438% 21.879 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 74% 0.965 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 41% 163 μg |

| Vitamin C | 4% 3.5 mg |

| Vitamin D | 26% 3.9 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 1% 11 mg |

| Iron | 13% 1.72 mg |

| Magnesium | 37% 132 mg |

| Manganese | 56% 1.176 mg |

| Phosphorus | 42% 294 mg |

| Potassium | 33% 1534 mg |

| Sodium | 1% 13 mg |

| Zinc | 81% 7.66 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 9.5 g |

| Selenium | 46 ug |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Nutrition

In a 100-gram (3 1⁄2-ounce) reference serving, raw shiitake mushrooms provide 140 kilojoules (34 kilocalories) of food energy and are 90% water, 7% carbohydrates, 2% protein and less than 1% fat (table for raw mushrooms). Raw shiitake mushrooms are rich sources (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of B vitamins and contain moderate levels of some dietary minerals (table). When dried to about 10% water, the contents of numerous nutrients increase substantially.

Like all mushrooms, shiitakes produce vitamin D2 upon exposure of their internal ergosterol to ultraviolet B (UVB) rays from sunlight or broadband UVB fluorescent tubes.[19][20]

Uses

Fresh and dried shiitake have many uses in East Asian cuisine. In Japan, they are served in miso soup, used as the basis for a kind of vegetarian dashi, and as an ingredient in many steamed and simmered dishes. In Chinese cuisine, they are often sautéed in vegetarian dishes such as Buddha's delight.

One type of high-grade shiitake is called donko (冬菇) in Japanese[21] and dōnggū in Chinese, literally "winter mushroom". Another high-grade of mushroom is called huāgū (花菇) in Chinese, literally "flower mushroom", which has a flower-like cracking pattern on the mushroom's upper surface. Both of these are produced at lower temperatures.

Research

Dermatitis

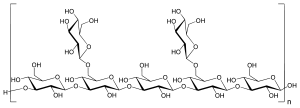

Rarely, consumption of raw or slightly cooked shiitake mushrooms may cause an allergic reaction called "shiitake dermatitis", including an erythematous, micro-papular, streaky pruriginous rash that occurs all over the body including face and scalp, appearing about 24 hours after consumption, possibly worsening by sun exposure and disappearing after 3 to 21 days.[22] This effect – presumably caused by the polysaccharide, lentinan[22] – is more common in East Asia,[23] but may be growing in occurrence in Europe as shiitake consumption increases.[22] Thorough cooking may eliminate the allergenicity.[24]

Gallery

- Shiitake growing wild in Hokkaido

Korean pyogo-bokkeum (stir-fried shiitake mushroom)

Korean pyogo-bokkeum (stir-fried shiitake mushroom)- Japanese ekiben shiitake-meshi (椎茸めし)

Lentinan, a beta-glucan isolated from the shiitake mushroom

Lentinan, a beta-glucan isolated from the shiitake mushroom Young Shiitake mushrooms on a log.

Young Shiitake mushrooms on a log.

See also

References

Citations

- Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- "Vitamins & Supplements SHIITAKE MUSHROOM". webmd.com. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- "Why Shiitake Mushrooms Are Good For You". healthline.com. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- Tremblay, Sylvie (21 November 2018). "What Are the Benefits of Shiitake Mushrooms?". healthyeating.sfgate.com. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- "Shiitake mushrooms: health benefits". accessscience.com. 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- Berkeley MJ. (1877). "Enumeration of the fungi collected during the Expedition of H.M.S. 'Challenger', 1874–75. (Third notice)". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 16 (89): 38–54. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1877.tb00170.x.

- Pegler D. (1975). "The classification of the genus Lentinus Fr. (Basidiomycota)". Kavaka. 3: 11–20.

- "GSD Species Synonymy: Lentinula edodes (Berk.) Pegler". Species Fungorum. CAB International. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Wasser S. (2004). "Shiitake (Lentinula edodes)". In Coates PM; Blackman M; Cragg GM; White JD; Moss J; Levine MA. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Dietary Supplements. CRC Press. pp. 653–64. ISBN 978-0-8247-5504-1.

- Halpern GM. (2007). Healing Mushrooms. Square One Publishers. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-7570-0196-3.

- Stamets 2000, p. 260

- 香菇简介 [Mushroom Introduction] (in Chinese). Yuwang jituan. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017.

- Miles PG; Chang S-T. (2004). Mushrooms: Cultivation, Nutritional Value, Medicinal Effect, and Environmental Impact. CRC Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-203-49208-6.

- Tilak, Shantanu (2019). "The Shiitake Mushroom-A History in Magic & Folklore" (PDF). The Mycophile. Vol. 59 no. 1. pp. 1, 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2019.

- Przybylowicz, Paul; Donoghue, John (1988). Shiitake Growers Handbook: The Art and Science of Mushroom Cultivation. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt. pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-0-8403-4962-0.

- Leatham GF. (1982). "Cultivation of shiitake, the Japanese forest mushroom, on logs: A potential industry for the United States" (PDF). Forest Products Journal. 32 (8): 29–35. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- Vane CH. (2003). "Monitoring decay of black gum wood (Nyssa sylvatica) during growth of the Shiitake mushroom (Lentinula edodes) using diffuse reflectance infrared spectroscopy". Applied Spectroscopy. 57 (5): 514–517. Bibcode:2003ApSpe..57..514V. doi:10.1366/000370203321666515. PMID 14658675.

- Vane CH; Drage TC; Snape CE. (2003). "Biodegradation of oak (Quercus alba) wood during growth of the Shiitake mushroom (Lentinula edodes): A molecular approach". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51 (4): 947–956. doi:10.1021/jf020932h. PMID 12568554.

- Bowerman, Susan (31 March 2008). "If mushrooms see the light". Los Angeles Times.

- Ko JA; Lee BH; Lee JS; Park HJ. (2008). "Effect of UV-B exposure on the concentration of vitamin D2 in sliced shiitake mushroom (Lentinus edodes) and white button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus)". J Agric Food Chem. 50 (10): 3671–3674. doi:10.1021/jf073398s. PMID 18442245.

- Chang TS; Hayes WA. (2013). The Biology and Cultivation of Edible Mushrooms. Elsevier Science. p. 470. ISBN 978-1-4832-7114-9.

- Boels D; Landreau A; Bruneau C; Garnier R; Pulce C; Labadie M; de Haro L; Harry P. (2014). "Shiitake dermatitis recorded by French Poison Control Centers – New case series with clinical observations". Clinical Toxicology. 52 (6): 625–8. doi:10.3109/15563650.2014.923905. PMID 24940644.

- Hérault M; Waton J; Bursztejn AC; Schmutz JL; Barbaud A. (2010). "Shiitake dermatitis now occurs in France". Annales de Dermatologie et de Vénéréologie. 137 (4): 290–3. doi:10.1016/j.annder.2010.02.007. PMID 20417363.

- Welbaum GE. (2015). Vegetable Production and Practices. CAB International. p. 445. ISBN 978-1-78064-534-6.

Cited literature

- Stamets, P. (2000). Growing Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms (3rd ed.). Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 978-1-58008-175-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links