Nanotechnology

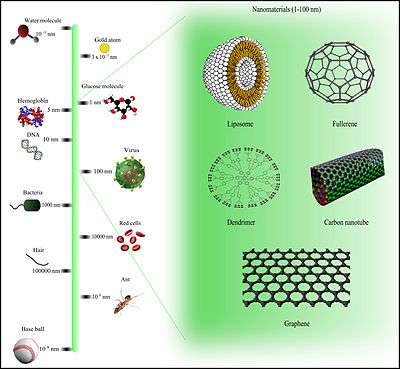

Nanotechnology (or "nanotech") is manipulation of matter on an atomic, molecular, and supramolecular scale. The earliest, widespread description of nanotechnology referred to the particular technological goal of precisely manipulating atoms and molecules for fabrication of macroscale products, also now referred to as molecular nanotechnology.[1][2] A more generalized description of nanotechnology was subsequently established by the National Nanotechnology Initiative, which defined nanotechnology as the manipulation of matter with at least one dimension sized from 1 to 100 nanometers. This definition reflects the fact that quantum mechanical effects are important at this quantum-realm scale, and so the definition shifted from a particular technological goal to a research category inclusive of all types of research and technologies that deal with the special properties of matter which occur below the given size threshold. It is therefore common to see the plural form "nanotechnologies" as well as "nanoscale technologies" to refer to the broad range of research and applications whose common trait is size.

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Nanotechnology |

|---|

| Impact and applications |

| Nanomaterials |

| Molecular self-assembly |

| Nanoelectronics |

| Nanometrology |

|

| Molecular nanotechnology |

|

Nanotechnology as defined by size is naturally broad, including fields of science as diverse as surface science, organic chemistry, molecular biology, semiconductor physics, energy storage,[3][4] engineering,[5] microfabrication,[6] and molecular engineering.[7] The associated research and applications are equally diverse, ranging from extensions of conventional device physics to completely new approaches based upon molecular self-assembly,[8] from developing new materials with dimensions on the nanoscale to direct control of matter on the atomic scale.

Scientists currently debate the future implications of nanotechnology. Nanotechnology may be able to create many new materials and devices with a vast range of applications, such as in nanomedicine, nanoelectronics, biomaterials energy production, and consumer products. On the other hand, nanotechnology raises many of the same issues as any new technology, including concerns about the toxicity and environmental impact of nanomaterials,[9] and their potential effects on global economics, as well as speculation about various doomsday scenarios. These concerns have led to a debate among advocacy groups and governments on whether special regulation of nanotechnology is warranted.

Origins

The concepts that seeded nanotechnology were first discussed in 1959 by renowned physicist Richard Feynman in his talk There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom, in which he described the possibility of synthesis via direct manipulation of atoms.

In 1960, Egyptian engineer Mohamed Atalla and Korean engineer Dawon Kahng at Bell Labs fabricated the first MOSFET (metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor) with a gate oxide thickness of 100 nm, along with a gate length of 20 µm.[10] In 1962, Atalla and Kahng fabricated a nanolayer-base metal–semiconductor junction (M–S junction) transistor that used gold (Au) thin films with a thickness of 10 nm.[11]

The term "nano-technology" was first used by Norio Taniguchi in 1974, though it was not widely known. Inspired by Feynman's concepts, K. Eric Drexler used the term "nanotechnology" in his 1986 book Engines of Creation: The Coming Era of Nanotechnology, which proposed the idea of a nanoscale "assembler" which would be able to build a copy of itself and of other items of arbitrary complexity with atomic control. Also in 1986, Drexler co-founded The Foresight Institute (with which he is no longer affiliated) to help increase public awareness and understanding of nanotechnology concepts and implications.

The emergence of nanotechnology as a field in the 1980s occurred through convergence of Drexler's theoretical and public work, which developed and popularized a conceptual framework for nanotechnology, and high-visibility experimental advances that drew additional wide-scale attention to the prospects of atomic control of matter. Since the popularity spike in the 1980s, most of nanotechnology has involved investigation of several approaches to making mechanical devices out of a small number of atoms.[12]

In the 1980s, two major breakthroughs sparked the growth of nanotechnology in modern era. First, the invention of the scanning tunneling microscope in 1981 which provided unprecedented visualization of individual atoms and bonds, and was successfully used to manipulate individual atoms in 1989. The microscope's developers Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer at IBM Zurich Research Laboratory received a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1986.[13][14] Binnig, Quate and Gerber also invented the analogous atomic force microscope that year.

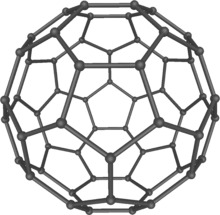

Second, fullerenes were discovered in 1985 by Harry Kroto, Richard Smalley, and Robert Curl, who together won the 1996 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[15][16] C60 was not initially described as nanotechnology; the term was used regarding subsequent work with related graphene tubes (called carbon nanotubes and sometimes called Bucky tubes) which suggested potential applications for nanoscale electronics and devices. The discovery of carbon nanotubes is largely attributed to Sumio Iijima of NEC in 1991,[17] for which Iijima won the inaugural 2008 Kavli Prize in Nanoscience.

In 1987, Bijan Davari led an IBM research team that demonstrated the first MOSFET with a 10 nm gate oxide thickness, using tungsten-gate technology.[18] Multi-gate MOSFETs enabled scaling below 20 nm gate length, starting with the FinFET (fin field-effect transistor), a three-dimensional, non-planar, double-gate MOSFET.[19] The FinFET originates from the research of Digh Hisamoto at Hitachi Central Research Laboratory in 1989.[20][21][22][23] At UC Berkeley, FinFET devices were fabricated by a group consisting of Hisamoto along with TSMC's Chenming Hu and other international researchers including Tsu-Jae King Liu, Jeffrey Bokor, Hideki Takeuchi, K. Asano, Jakub Kedziersk, Xuejue Huang, Leland Chang, Nick Lindert, Shibly Ahmed and Cyrus Tabery. The team fabricated FinFET devices down to a 17 nm process in 1998, and then 15 nm in 2001. In 2002, a team including Yu, Chang, Ahmed, Hu, Liu, Bokor and Tabery fabricated a 10 nm FinFET device.[19]

In the early 2000s, the field garnered increased scientific, political, and commercial attention that led to both controversy and progress. Controversies emerged regarding the definitions and potential implications of nanotechnologies, exemplified by the Royal Society's report on nanotechnology.[24] Challenges were raised regarding the feasibility of applications envisioned by advocates of molecular nanotechnology, which culminated in a public debate between Drexler and Smalley in 2001 and 2003.[25]

Meanwhile, commercialization of products based on advancements in nanoscale technologies began emerging. These products are limited to bulk applications of nanomaterials and do not involve atomic control of matter. Some examples include the Silver Nano platform for using silver nanoparticles as an antibacterial agent, nanoparticle-based transparent sunscreens, carbon fiber strengthening using silica nanoparticles, and carbon nanotubes for stain-resistant textiles.[26][27]

Governments moved to promote and fund research into nanotechnology, such as in the U.S. with the National Nanotechnology Initiative, which formalized a size-based definition of nanotechnology and established funding for research on the nanoscale, and in Europe via the European Framework Programmes for Research and Technological Development.

By the mid-2000s new and serious scientific attention began to flourish. Projects emerged to produce nanotechnology roadmaps[28][29] which center on atomically precise manipulation of matter and discuss existing and projected capabilities, goals, and applications.

In 2006, a team of Korean researchers from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) and the National Nano Fab Center developed a 3 nm MOSFET, the world's smallest nanoelectronic device. It was based on gate-all-around (GAA) FinFET technology.[30][31]

Over sixty countries created nanotechnology research and development (R&D) government programs between 2001 and 2004. Government funding was exceeded by corporate spending on nanotechnology R&D, with most of the funding coming from corporations based in the United States, Japan and Germany. The top five organizations that filed the most intellectual patents on nanotechnology R&D between 1970 and 2011 were Samsung Electronics (2,578 first patents), Nippon Steel (1,490 first patents), IBM (1,360 first patents), Toshiba (1,298 first patents) and Canon (1,162 first patents). The top five organizations that published the most scientific papers on nanotechnology research between 1970 and 2012 were the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Russian Academy of Sciences, Centre national de la recherche scientifique, University of Tokyo and Osaka University.[32]

Fundamental concepts

Nanotechnology is the engineering of functional systems at the molecular scale. This covers both current work and concepts that are more advanced. In its original sense, nanotechnology refers to the projected ability to construct items from the bottom up, using techniques and tools being developed today to make complete, high performance products.

One nanometer (nm) is one billionth, or 10−9, of a meter. By comparison, typical carbon-carbon bond lengths, or the spacing between these atoms in a molecule, are in the range 0.12–0.15 nm, and a DNA double-helix has a diameter around 2 nm. On the other hand, the smallest cellular life-forms, the bacteria of the genus Mycoplasma, are around 200 nm in length. By convention, nanotechnology is taken as the scale range 1 to 100 nm following the definition used by the National Nanotechnology Initiative in the US. The lower limit is set by the size of atoms (hydrogen has the smallest atoms, which are approximately a quarter of a nm kinetic diameter) since nanotechnology must build its devices from atoms and molecules. The upper limit is more or less arbitrary but is around the size below which phenomena not observed in larger structures start to become apparent and can be made use of in the nano device.[33] These new phenomena make nanotechnology distinct from devices which are merely miniaturised versions of an equivalent macroscopic device; such devices are on a larger scale and come under the description of microtechnology.[34]

To put that scale in another context, the comparative size of a nanometer to a meter is the same as that of a marble to the size of the earth.[35] Or another way of putting it: a nanometer is the amount an average man's beard grows in the time it takes him to raise the razor to his face.[35]

Two main approaches are used in nanotechnology. In the "bottom-up" approach, materials and devices are built from molecular components which assemble themselves chemically by principles of molecular recognition.[36] In the "top-down" approach, nano-objects are constructed from larger entities without atomic-level control.[37]

Areas of physics such as nanoelectronics, nanomechanics, nanophotonics and nanoionics have evolved during the last few decades to provide a basic scientific foundation of nanotechnology.

Larger to smaller: a materials perspective

Several phenomena become pronounced as the size of the system decreases. These include statistical mechanical effects, as well as quantum mechanical effects, for example the "quantum size effect" where the electronic properties of solids are altered with great reductions in particle size. This effect does not come into play by going from macro to micro dimensions. However, quantum effects can become significant when the nanometer size range is reached, typically at distances of 100 nanometers or less, the so-called quantum realm. Additionally, a number of physical (mechanical, electrical, optical, etc.) properties change when compared to macroscopic systems. One example is the increase in surface area to volume ratio altering mechanical, thermal and catalytic properties of materials. Diffusion and reactions at nanoscale, nanostructures materials and nanodevices with fast ion transport are generally referred to nanoionics. Mechanical properties of nanosystems are of interest in the nanomechanics research. The catalytic activity of nanomaterials also opens potential risks in their interaction with biomaterials.

Materials reduced to the nanoscale can show different properties compared to what they exhibit on a macroscale, enabling unique applications. For instance, opaque substances can become transparent (copper); stable materials can turn combustible (aluminium); insoluble materials may become soluble (gold). A material such as gold, which is chemically inert at normal scales, can serve as a potent chemical catalyst at nanoscales. Much of the fascination with nanotechnology stems from these quantum and surface phenomena that matter exhibits at the nanoscale.[38]

Simple to complex: a molecular perspective

Modern synthetic chemistry has reached the point where it is possible to prepare small molecules to almost any structure. These methods are used today to manufacture a wide variety of useful chemicals such as pharmaceuticals or commercial polymers. This ability raises the question of extending this kind of control to the next-larger level, seeking methods to assemble these single molecules into supramolecular assemblies consisting of many molecules arranged in a well defined manner.

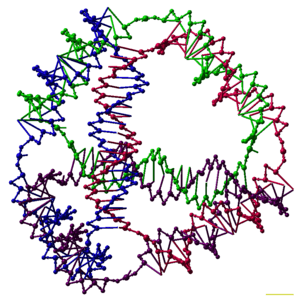

These approaches utilize the concepts of molecular self-assembly and/or supramolecular chemistry to automatically arrange themselves into some useful conformation through a bottom-up approach. The concept of molecular recognition is especially important: molecules can be designed so that a specific configuration or arrangement is favored due to non-covalent intermolecular forces. The Watson–Crick basepairing rules are a direct result of this, as is the specificity of an enzyme being targeted to a single substrate, or the specific folding of the protein itself. Thus, two or more components can be designed to be complementary and mutually attractive so that they make a more complex and useful whole.

Such bottom-up approaches should be capable of producing devices in parallel and be much cheaper than top-down methods, but could potentially be overwhelmed as the size and complexity of the desired assembly increases. Most useful structures require complex and thermodynamically unlikely arrangements of atoms. Nevertheless, there are many examples of self-assembly based on molecular recognition in biology, most notably Watson–Crick basepairing and enzyme-substrate interactions. The challenge for nanotechnology is whether these principles can be used to engineer new constructs in addition to natural ones.

Molecular nanotechnology: a long-term view

Molecular nanotechnology, sometimes called molecular manufacturing, describes engineered nanosystems (nanoscale machines) operating on the molecular scale. Molecular nanotechnology is especially associated with the molecular assembler, a machine that can produce a desired structure or device atom-by-atom using the principles of mechanosynthesis. Manufacturing in the context of productive nanosystems is not related to, and should be clearly distinguished from, the conventional technologies used to manufacture nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes and nanoparticles.

When the term "nanotechnology" was independently coined and popularized by Eric Drexler (who at the time was unaware of an earlier usage by Norio Taniguchi) it referred to a future manufacturing technology based on molecular machine systems. The premise was that molecular scale biological analogies of traditional machine components demonstrated molecular machines were possible: by the countless examples found in biology, it is known that sophisticated, stochastically optimised biological machines can be produced.

It is hoped that developments in nanotechnology will make possible their construction by some other means, perhaps using biomimetic principles. However, Drexler and other researchers[39] have proposed that advanced nanotechnology, although perhaps initially implemented by biomimetic means, ultimately could be based on mechanical engineering principles, namely, a manufacturing technology based on the mechanical functionality of these components (such as gears, bearings, motors, and structural members) that would enable programmable, positional assembly to atomic specification.[40] The physics and engineering performance of exemplar designs were analyzed in Drexler's book Nanosystems.

In general it is very difficult to assemble devices on the atomic scale, as one has to position atoms on other atoms of comparable size and stickiness. Another view, put forth by Carlo Montemagno,[41] is that future nanosystems will be hybrids of silicon technology and biological molecular machines. Richard Smalley argued that mechanosynthesis are impossible due to the difficulties in mechanically manipulating individual molecules.

This led to an exchange of letters in the ACS publication Chemical & Engineering News in 2003.[42] Though biology clearly demonstrates that molecular machine systems are possible, non-biological molecular machines are today only in their infancy. Leaders in research on non-biological molecular machines are Dr. Alex Zettl and his colleagues at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratories and UC Berkeley. They have constructed at least three distinct molecular devices whose motion is controlled from the desktop with changing voltage: a nanotube nanomotor, a molecular actuator,[43] and a nanoelectromechanical relaxation oscillator.[44] See nanotube nanomotor for more examples.

An experiment indicating that positional molecular assembly is possible was performed by Ho and Lee at Cornell University in 1999. They used a scanning tunneling microscope to move an individual carbon monoxide molecule (CO) to an individual iron atom (Fe) sitting on a flat silver crystal, and chemically bound the CO to the Fe by applying a voltage.

Current research

Nanomaterials

The nanomaterials field includes subfields which develop or study materials having unique properties arising from their nanoscale dimensions.[47]

- Interface and colloid science has given rise to many materials which may be useful in nanotechnology, such as carbon nanotubes and other fullerenes, and various nanoparticles and nanorods. Nanomaterials with fast ion transport are related also to nanoionics and nanoelectronics.

- Nanoscale materials can also be used for bulk applications; most present commercial applications of nanotechnology are of this flavor.

- Progress has been made in using these materials for medical applications; see Nanomedicine.

- Nanoscale materials such as nanopillars are sometimes used in solar cells which combats the cost of traditional silicon solar cells.

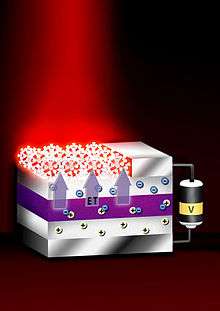

- Development of applications incorporating semiconductor nanoparticles to be used in the next generation of products, such as display technology, lighting, solar cells and biological imaging; see quantum dots.

- Recent application of nanomaterials include a range of biomedical applications, such as tissue engineering, drug delivery, and biosensors.[48][49][50][51]

Bottom-up approaches

These seek to arrange smaller components into more complex assemblies.

- DNA nanotechnology utilizes the specificity of Watson–Crick basepairing to construct well-defined structures out of DNA and other nucleic acids.

- Approaches from the field of "classical" chemical synthesis (Inorganic and organic synthesis) also aim at designing molecules with well-defined shape (e.g. bis-peptides[52]).

- More generally, molecular self-assembly seeks to use concepts of supramolecular chemistry, and molecular recognition in particular, to cause single-molecule components to automatically arrange themselves into some useful conformation.

- Atomic force microscope tips can be used as a nanoscale "write head" to deposit a chemical upon a surface in a desired pattern in a process called dip pen nanolithography. This technique fits into the larger subfield of nanolithography.

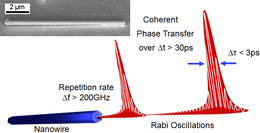

- Molecular Beam Epitaxy allows for bottom up assemblies of materials, most notably semiconductor materials commonly used in chip and computing applications, stacks, gating, and nanowire lasers.

Top-down approaches

These seek to create smaller devices by using larger ones to direct their assembly.

- Many technologies that descended from conventional solid-state silicon methods for fabricating microprocessors are now capable of creating features smaller than 100 nm, falling under the definition of nanotechnology. Giant magnetoresistance-based hard drives already on the market fit this description,[53] as do atomic layer deposition (ALD) techniques. Peter Grünberg and Albert Fert received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2007 for their discovery of Giant magnetoresistance and contributions to the field of spintronics.[54]

- Solid-state techniques can also be used to create devices known as nanoelectromechanical systems or NEMS, which are related to microelectromechanical systems or MEMS.

- Focused ion beams can directly remove material, or even deposit material when suitable precursor gasses are applied at the same time. For example, this technique is used routinely to create sub-100 nm sections of material for analysis in Transmission electron microscopy.

- Atomic force microscope tips can be used as a nanoscale "write head" to deposit a resist, which is then followed by an etching process to remove material in a top-down method.

Functional approaches

These seek to develop components of a desired functionality without regard to how they might be assembled.

- Magnetic assembly for the synthesis of anisotropic superparamagnetic materials such as recently presented magnetic nano chains.[36]

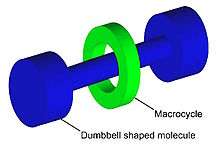

- Molecular scale electronics seeks to develop molecules with useful electronic properties. These could then be used as single-molecule components in a nanoelectronic device.[55] For an example see rotaxane.

- Synthetic chemical methods can also be used to create synthetic molecular motors, such as in a so-called nanocar.

Biomimetic approaches

- Bionics or biomimicry seeks to apply biological methods and systems found in nature, to the study and design of engineering systems and modern technology. Biomineralization is one example of the systems studied.

- Bionanotechnology is the use of biomolecules for applications in nanotechnology, including use of viruses and lipid assemblies.[56][57] Nanocellulose is a potential bulk-scale application.

Speculative

These subfields seek to anticipate what inventions nanotechnology might yield, or attempt to propose an agenda along which inquiry might progress. These often take a big-picture view of nanotechnology, with more emphasis on its societal implications than the details of how such inventions could actually be created.

- Molecular nanotechnology is a proposed approach which involves manipulating single molecules in finely controlled, deterministic ways. This is more theoretical than the other subfields, and many of its proposed techniques are beyond current capabilities.

- Nanorobotics centers on self-sufficient machines of some functionality operating at the nanoscale. There are hopes for applying nanorobots in medicine.[58][59] Nevertheless, progress on innovative materials and methodologies has been demonstrated with some patents granted about new nanomanufacturing devices for future commercial applications, which also progressively helps in the development towards nanorobots with the use of embedded nanobioelectronics concepts.[60][61]

- Productive nanosystems are "systems of nanosystems" which will be complex nanosystems that produce atomically precise parts for other nanosystems, not necessarily using novel nanoscale-emergent properties, but well-understood fundamentals of manufacturing. Because of the discrete (i.e. atomic) nature of matter and the possibility of exponential growth, this stage is seen as the basis of another industrial revolution. Mihail Roco, one of the architects of the USA's National Nanotechnology Initiative, has proposed four states of nanotechnology that seem to parallel the technical progress of the Industrial Revolution, progressing from passive nanostructures to active nanodevices to complex nanomachines and ultimately to productive nanosystems.[62]

- Programmable matter seeks to design materials whose properties can be easily, reversibly and externally controlled though a fusion of information science and materials science.

- Due to the popularity and media exposure of the term nanotechnology, the words picotechnology and femtotechnology have been coined in analogy to it, although these are only used rarely and informally.

Dimensionality in nanomaterials

Nanomaterials can be classified in 0D, 1D, 2D and 3D nanomaterials. The dimensionality play a major role in determining the characteristic of nanomaterials including physical, chemical and biological characteristics. With the decrease in dimensionality, an increase in surface-to-volume ratio is observed. This indicate that smaller dimensional nanomaterials have higher surface area compared to 3D nanomaterials. Recently, two dimensional (2D) nanomaterials are extensively investigated for electronic, biomedical, drug delivery and biosensor applications.

Tools and techniques

There are several important modern developments. The atomic force microscope (AFM) and the Scanning Tunneling Microscope (STM) are two early versions of scanning probes that launched nanotechnology. There are other types of scanning probe microscopy. Although conceptually similar to the scanning confocal microscope developed by Marvin Minsky in 1961 and the scanning acoustic microscope (SAM) developed by Calvin Quate and coworkers in the 1970s, newer scanning probe microscopes have much higher resolution, since they are not limited by the wavelength of sound or light.

The tip of a scanning probe can also be used to manipulate nanostructures (a process called positional assembly). Feature-oriented scanning methodology may be a promising way to implement these nanomanipulations in automatic mode.[63][64] However, this is still a slow process because of low scanning velocity of the microscope.

Various techniques of nanolithography such as optical lithography, X-ray lithography, dip pen nanolithography, electron beam lithography or nanoimprint lithography were also developed. Lithography is a top-down fabrication technique where a bulk material is reduced in size to nanoscale pattern.

Another group of nanotechnological techniques include those used for fabrication of nanotubes and nanowires, those used in semiconductor fabrication such as deep ultraviolet lithography, electron beam lithography, focused ion beam machining, nanoimprint lithography, atomic layer deposition, and molecular vapor deposition, and further including molecular self-assembly techniques such as those employing di-block copolymers. The precursors of these techniques preceded the nanotech era, and are extensions in the development of scientific advancements rather than techniques which were devised with the sole purpose of creating nanotechnology and which were results of nanotechnology research.[65]

The top-down approach anticipates nanodevices that must be built piece by piece in stages, much as manufactured items are made. Scanning probe microscopy is an important technique both for characterization and synthesis of nanomaterials. Atomic force microscopes and scanning tunneling microscopes can be used to look at surfaces and to move atoms around. By designing different tips for these microscopes, they can be used for carving out structures on surfaces and to help guide self-assembling structures. By using, for example, feature-oriented scanning approach, atoms or molecules can be moved around on a surface with scanning probe microscopy techniques.[63][64] At present, it is expensive and time-consuming for mass production but very suitable for laboratory experimentation.

In contrast, bottom-up techniques build or grow larger structures atom by atom or molecule by molecule. These techniques include chemical synthesis, self-assembly and positional assembly. Dual polarisation interferometry is one tool suitable for characterisation of self assembled thin films. Another variation of the bottom-up approach is molecular beam epitaxy or MBE. Researchers at Bell Telephone Laboratories like John R. Arthur. Alfred Y. Cho, and Art C. Gossard developed and implemented MBE as a research tool in the late 1960s and 1970s. Samples made by MBE were key to the discovery of the fractional quantum Hall effect for which the 1998 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded. MBE allows scientists to lay down atomically precise layers of atoms and, in the process, build up complex structures. Important for research on semiconductors, MBE is also widely used to make samples and devices for the newly emerging field of spintronics.

However, new therapeutic products, based on responsive nanomaterials, such as the ultradeformable, stress-sensitive Transfersome vesicles, are under development and already approved for human use in some countries.[66]

Research and development

Because of the variety of potential applications (including industrial and military), governments have invested billions of dollars in nanotechnology research. Prior to 2012, the USA invested $3.7 billion using its National Nanotechnology Initiative, the European Union invested $1.2 billion, and Japan invested $750 million.[67] Over sixty countries created nanotechnology research and development (R&D) programs between 2001 and 2004. In 2012, the US and EU each invested $2.1 billion on nanotechnology research, followed by Japan with $1.2 billion. Global investment reached $7.9 billion in 2012. Government funding was exceeded by corporate R&D spending on nanotechnology research, which was $10 billion in 2012. The largest corporate R&D spenders were from the US, Japan and Germany which accounted for a combined $7.1 billion.[32]

| Rank | Organization | Country | First patents |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Samsung Electronics | South Korea | 2,578 |

| 2 | Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal | Japan | 1,490 |

| 3 | IBM | United States | 1,360 |

| 4 | Toshiba | Japan | 1,298 |

| 5 | Canon Inc. | Japan | 1,162 |

| 6 | Hitachi | Japan | 1,100 |

| 7 | University of California, Berkeley | United States | 1,055 |

| 8 | Panasonic | Japan | 1,047 |

| 9 | Hewlett-Packard | United States | 880 |

| 10 | TDK | Japan | 839 |

| Rank | Organization | Country | Scientific publications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chinese Academy of Sciences | China | 29,591 |

| 2 | Russian Academy of Sciences | Russia | 12,543 |

| 3 | Centre national de la recherche scientifique | France | 8,105 |

| 4 | University of Tokyo | Japan | 6,932 |

| 5 | Osaka University | Japan | 6,613 |

| 6 | Tohoku University | Japan | 6,266 |

| 7 | University of California, Berkeley | United States | 5,936 |

| 8 | Spanish National Research Council | Spain | 5,585 |

| 9 | University of Illinois | United States | 5,580 |

| 10 | MIT | United States | 5,567 |

Applications

As of August 21, 2008, the Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies estimates that over 800 manufacturer-identified nanotech products are publicly available, with new ones hitting the market at a pace of 3–4 per week.[27] The project lists all of the products in a publicly accessible online database. Most applications are limited to the use of "first generation" passive nanomaterials which includes titanium dioxide in sunscreen, cosmetics, surface coatings,[68] and some food products; Carbon allotropes used to produce gecko tape; silver in food packaging, clothing, disinfectants and household appliances; zinc oxide in sunscreens and cosmetics, surface coatings, paints and outdoor furniture varnishes; and cerium oxide as a fuel catalyst.[26]

Further applications allow tennis balls to last longer, golf balls to fly straighter, and even bowling balls to become more durable and have a harder surface. Trousers and socks have been infused with nanotechnology so that they will last longer and keep people cool in the summer. Bandages are being infused with silver nanoparticles to heal cuts faster.[69] Video game consoles and personal computers may become cheaper, faster, and contain more memory thanks to nanotechnology.[70] Also, to build structures for on chip computing with light, for example on chip optical quantum information processing, and picosecond transmission of information.[71]

Nanotechnology may have the ability to make existing medical applications cheaper and easier to use in places like the general practitioner's office and at home.[72] Cars are being manufactured with nanomaterials so they may need fewer metals and less fuel to operate in the future.[73]

Scientists are now turning to nanotechnology in an attempt to develop diesel engines with cleaner exhaust fumes. Platinum is currently used as the diesel engine catalyst in these engines. The catalyst is what cleans the exhaust fume particles. First a reduction catalyst is employed to take nitrogen atoms from NOx molecules in order to free oxygen. Next the oxidation catalyst oxidizes the hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide to form carbon dioxide and water.[74] Platinum is used in both the reduction and the oxidation catalysts.[75] Using platinum though, is inefficient in that it is expensive and unsustainable. Danish company InnovationsFonden invested DKK 15 million in a search for new catalyst substitutes using nanotechnology. The goal of the project, launched in the autumn of 2014, is to maximize surface area and minimize the amount of material required. Objects tend to minimize their surface energy; two drops of water, for example, will join to form one drop and decrease surface area. If the catalyst's surface area that is exposed to the exhaust fumes is maximized, efficiency of the catalyst is maximized. The team working on this project aims to create nanoparticles that will not merge. Every time the surface is optimized, material is saved. Thus, creating these nanoparticles will increase the effectiveness of the resulting diesel engine catalyst—in turn leading to cleaner exhaust fumes—and will decrease cost. If successful, the team hopes to reduce platinum use by 25%.[76]

Nanotechnology also has a prominent role in the fast developing field of Tissue Engineering. When designing scaffolds, researchers attempt to mimic the nanoscale features of a cell's microenvironment to direct its differentiation down a suitable lineage.[77] For example, when creating scaffolds to support the growth of bone, researchers may mimic osteoclast resorption pits.[78]

Researchers have successfully used DNA origami-based nanobots capable of carrying out logic functions to achieve targeted drug delivery in cockroaches. It is said that the computational power of these nanobots can be scaled up to that of a Commodore 64.[79]

Nanoelectronics

Commercial nanoelectronic semiconductor device fabrication began in the 2010s. In 2013, SK Hynix began commercial mass-production of a 16 nm process,[80] TSMC began production of a 16 nm FinFET process,[81] and Samsung Electronics began production of a 10 nm process.[82] TSMC began production of a 7 nm process in 2017,[83] and Samsung began production of a 5 nm process in 2018.[84] In 2019, Samsung announced plans for the commercial production of a 3 nm GAAFET process by 2021.[85]

Commercial production of nanoelectronic semiconductor memory also began in the 2010s. In 2013, SK Hynix began mass-production of 16 nm NAND flash memory,[80] and Samsung began production of 10 nm multi-level cell (MLC) NAND flash memory.[82] In 2017, TSMC began production of SRAM memory using a 7 nm process.[83]

Implications

An area of concern is the effect that industrial-scale manufacturing and use of nanomaterials would have on human health and the environment, as suggested by nanotoxicology research. For these reasons, some groups advocate that nanotechnology be regulated by governments. Others counter that overregulation would stifle scientific research and the development of beneficial innovations. Public health research agencies, such as the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health are actively conducting research on potential health effects stemming from exposures to nanoparticles.[86][87]

Some nanoparticle products may have unintended consequences. Researchers have discovered that bacteriostatic silver nanoparticles used in socks to reduce foot odor are being released in the wash.[88] These particles are then flushed into the waste water stream and may destroy bacteria which are critical components of natural ecosystems, farms, and waste treatment processes.[89]

Public deliberations on risk perception in the US and UK carried out by the Center for Nanotechnology in Society found that participants were more positive about nanotechnologies for energy applications than for health applications, with health applications raising moral and ethical dilemmas such as cost and availability.[90]

Experts, including director of the Woodrow Wilson Center's Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies David Rejeski, have testified[91] that successful commercialization depends on adequate oversight, risk research strategy, and public engagement. Berkeley, California is currently the only city in the United States to regulate nanotechnology;[92] Cambridge, Massachusetts in 2008 considered enacting a similar law,[93] but ultimately rejected it.[94] Over the next several decades, applications of nanotechnology will likely include much higher-capacity computers, active materials of various kinds, and cellular-scale biomedical devices.[12]

Health and environmental concerns

Nanofibers are used in several areas and in different products, in everything from aircraft wings to tennis rackets. Inhaling airborne nanoparticles and nanofibers may lead to a number of pulmonary diseases, e.g. fibrosis.[95] Researchers have found that when rats breathed in nanoparticles, the particles settled in the brain and lungs, which led to significant increases in biomarkers for inflammation and stress response[96] and that nanoparticles induce skin aging through oxidative stress in hairless mice.[97][98]

A two-year study at UCLA's School of Public Health found lab mice consuming nano-titanium dioxide showed DNA and chromosome damage to a degree "linked to all the big killers of man, namely cancer, heart disease, neurological disease and aging".[99]

A major study published more recently in Nature Nanotechnology suggests some forms of carbon nanotubes – a poster child for the "nanotechnology revolution" – could be as harmful as asbestos if inhaled in sufficient quantities. Anthony Seaton of the Institute of Occupational Medicine in Edinburgh, Scotland, who contributed to the article on carbon nanotubes said "We know that some of them probably have the potential to cause mesothelioma. So those sorts of materials need to be handled very carefully."[100] In the absence of specific regulation forthcoming from governments, Paull and Lyons (2008) have called for an exclusion of engineered nanoparticles in food.[101] A newspaper article reports that workers in a paint factory developed serious lung disease and nanoparticles were found in their lungs.[102][103][104][105]

Regulation

Calls for tighter regulation of nanotechnology have occurred alongside a growing debate related to the human health and safety risks of nanotechnology.[106] There is significant debate about who is responsible for the regulation of nanotechnology. Some regulatory agencies currently cover some nanotechnology products and processes (to varying degrees) – by "bolting on" nanotechnology to existing regulations – there are clear gaps in these regimes.[107] Davies (2008) has proposed a regulatory road map describing steps to deal with these shortcomings.[108]

Stakeholders concerned by the lack of a regulatory framework to assess and control risks associated with the release of nanoparticles and nanotubes have drawn parallels with bovine spongiform encephalopathy ("mad cow" disease), thalidomide, genetically modified food,[109] nuclear energy, reproductive technologies, biotechnology, and asbestosis. Dr. Andrew Maynard, chief science advisor to the Woodrow Wilson Center's Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies, concludes that there is insufficient funding for human health and safety research, and as a result there is currently limited understanding of the human health and safety risks associated with nanotechnology.[110] As a result, some academics have called for stricter application of the precautionary principle, with delayed marketing approval, enhanced labelling and additional safety data development requirements in relation to certain forms of nanotechnology.[111][112]

The Royal Society report[24] identified a risk of nanoparticles or nanotubes being released during disposal, destruction and recycling, and recommended that "manufacturers of products that fall under extended producer responsibility regimes such as end-of-life regulations publish procedures outlining how these materials will be managed to minimize possible human and environmental exposure" (p. xiii).

The Center for Nanotechnology in Society has found that people respond to nanotechnologies differently, depending on application – with participants in public deliberations more positive about nanotechnologies for energy than health applications – suggesting that any public calls for nano regulations may differ by technology sector.[90]

See also

- Carbon nanotube

- Electrostatic deflection (molecular physics/nanotechnology)

- Energy applications of nanotechnology

- Ethics of nanotechnologies

- Ion implantation-induced nanoparticle formation

- Gold nanoparticle

- List of emerging technologies

- List of nanotechnology organizations

- List of software for nanostructures modeling

- Magnetic nanochains

- Materiomics

- Nano-thermite

- Molecular design software

- Molecular mechanics

- Nanobiotechnology

- Nanoelectromechanical relay

- Nanoengineering

- Nanofluidics

- NanoHUB

- Nanometrology

- Nanoparticle

- Nanoscale networks

- Nanotechnology education

- Nanotechnology in fiction

- Nanotechnology in water treatment

- Nanoweapons

- National Nanotechnology Initiative

- Self-assembly of nanoparticles

- Top-down and bottom-up

- Translational research

- Wet nanotechnology

References

- Drexler, K. Eric (1986). Engines of Creation: The Coming Era of Nanotechnology. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-19973-5.

- Drexler, K. Eric (1992). Nanosystems: Molecular Machinery, Manufacturing, and Computation. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-57547-4.

- Hubler, A. (2010). "Digital quantum batteries: Energy and information storage in nanovacuum tube arrays". Complexity. 15 (5): 48–55. doi:10.1002/cplx.20306. S2CID 6994736.

- Shinn, E. (2012). "Nuclear energy conversion with stacks of graphene nanocapacitors". Complexity. 18 (3): 24–27. Bibcode:2013Cmplx..18c..24S. doi:10.1002/cplx.21427. S2CID 35742708.

- Elishakoff,I., D. Pentaras, K. Dujat, C. Versaci, G. Muscolino, J. Storch, S. Bucas, N. Challamel, T. Natsuki, Y.Y. Zhang, C.M. Wang and G. Ghyselinck, Carbon Nanotubes and Nano Sensors: Vibrations, Buckling, and Ballistic Impact, ISTE-Wiley, London, 2012, XIII+pp.421; ISBN 978-1-84821-345-6.

- Lyon, David; et., al. (2013). "Gap size dependence of the dielectric strength in nano vacuum gaps". IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation. 20 (4): 1467–1471. doi:10.1109/TDEI.2013.6571470.

- Saini, Rajiv; Saini, Santosh; Sharma, Sugandha (2010). "Nanotechnology: The Future Medicine". Journal of Cutaneous and Aesthetic Surgery. 3 (1): 32–33. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.63301. PMC 2890134. PMID 20606992.

- Belkin, A.; et., al. (2015). "Self-Assembled Wiggling Nano-Structures and the Principle of Maximum Entropy Production". Sci. Rep. 5: 8323. Bibcode:2015NatSR...5E8323B. doi:10.1038/srep08323. PMC 4321171. PMID 25662746.

- Buzea, C.; Pacheco, I. I.; Robbie, K. (2007). "Nanomaterials and nanoparticles: Sources and toxicity". Biointerphases. 2 (4): MR17–MR71. arXiv:0801.3280. doi:10.1116/1.2815690. PMID 20419892.

- Sze, Simon M. (2002). Semiconductor Devices: Physics and Technology (PDF) (2nd ed.). Wiley. p. 4. ISBN 0-471-33372-7.

- Pasa, André Avelino (2010). "Chapter 13: Metal Nanolayer-Base Transistor". Handbook of Nanophysics: Nanoelectronics and Nanophotonics. CRC Press. pp. 13–1, 13–4. ISBN 9781420075519.

- Wolfram, Stephen (2002). A New Kind of Science. Wolfram Media, Inc. p. 1193. ISBN 978-1-57955-008-0.

- Binnig, G.; Rohrer, H. (1986). "Scanning tunneling microscopy". IBM Journal of Research and Development. 30 (4): 355–69.

- "Press Release: the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physics". Nobelprize.org. 15 October 1986. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- Kroto, H. W.; Heath, J. R.; O'Brien, S. C.; Curl, R. F.; Smalley, R. E. (1985). "C60: Buckminsterfullerene". Nature. 318 (6042): 162–163. Bibcode:1985Natur.318..162K. doi:10.1038/318162a0.

- Adams, W. W.; Baughman, R. H. (2005). "RETROSPECTIVE: Richard E. Smalley (1943-2005)". Science. 310 (5756): 1916. doi:10.1126/science.1122120. PMID 16373566.

- Monthioux, Marc; Kuznetsov, V (2006). "Who should be given the credit for the discovery of carbon nanotubes?" (PDF). Carbon. 44 (9): 1621–1623. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2006.03.019.

- Davari, Bijan; Ting, Chung-Yu; Ahn, Kie Y.; Basavaiah, S.; Hu, Chao-Kun; Taur, Yuan; Wordeman, Matthew R.; Aboelfotoh, O.; Krusin-Elbaum, L.; Joshi, Rajiv V.; Polcari, Michael R. (1987). "Submicron Tungsten Gate MOSFET with 10 nm Gate Oxide". 1987 Symposium on VLSI Technology. Digest of Technical Papers: 61–62.

- Tsu‐Jae King, Liu (June 11, 2012). "FinFET: History, Fundamentals and Future". University of California, Berkeley. Symposium on VLSI Technology Short Course. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- Colinge, J.P. (2008). FinFETs and Other Multi-Gate Transistors. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 11. ISBN 9780387717517.

- Hisamoto, D.; Kaga, T.; Kawamoto, Y.; Takeda, E. (December 1989). "A fully depleted lean-channel transistor (DELTA)-a novel vertical ultra thin SOI MOSFET". International Technical Digest on Electron Devices Meeting: 833–836. doi:10.1109/IEDM.1989.74182.

- "IEEE Andrew S. Grove Award Recipients". IEEE Andrew S. Grove Award. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- "The Breakthrough Advantage for FPGAs with Tri-Gate Technology" (PDF). Intel. 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- "Nanoscience and nanotechnologies: opportunities and uncertainties". Royal Society and Royal Academy of Engineering. July 2004. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- "Nanotechnology: Drexler and Smalley make the case for and against 'molecular assemblers'". Chemical & Engineering News. 81 (48): 37–42. 1 December 2003. doi:10.1021/cen-v081n036.p037. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- "Nanotechnology Information Center: Properties, Applications, Research, and Safety Guidelines". American Elements. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- "Analysis: This is the first publicly available on-line inventory of nanotechnology-based consumer products". The Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies. 2008. Archived from the original on 5 May 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- "Productive Nanosystems Technology Roadmap" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-09-08.

- "NASA Draft Nanotechnology Roadmap" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-01-22.

- "Still Room at the Bottom (nanometer transistor developed by Yang-kyu Choi from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology)", Nanoparticle News, 1 April 2006, archived from the original on 6 November 2012

- Lee, Hyunjin; et al. (2006), "Sub-5nm All-Around Gate FinFET for Ultimate Scaling", Symposium on VLSI Technology, 2006: 58–59, doi:10.1109/VLSIT.2006.1705215, hdl:10203/698, ISBN 978-1-4244-0005-8

- World Intellectual Property Report: Breakthrough Innovation and Economic Growth (PDF). World Intellectual Property Organization. 2015. pp. 112–4. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- Allhoff, Fritz; Lin, Patrick; Moore, Daniel (2010). What is nanotechnology and why does it matter?: from science to ethics. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-1-4051-7545-6.

- Prasad, S. K. (2008). Modern Concepts in Nanotechnology. Discovery Publishing House. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-81-8356-296-6.

- Kahn, Jennifer (2006). "Nanotechnology". National Geographic. 2006 (June): 98–119.

- Kralj, Slavko; Makovec, Darko (27 October 2015). "Magnetic Assembly of Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Clusters into Nanochains and Nanobundles". ACS Nano. 9 (10): 9700–9707. doi:10.1021/acsnano.5b02328. PMID 26394039.

- Rodgers, P. (2006). "Nanoelectronics: Single file". Nature Nanotechnology. doi:10.1038/nnano.2006.5.

- Lubick N; Betts, Kellyn (2008). "Silver socks have cloudy lining". Environ Sci Technol. 42 (11): 3910. Bibcode:2008EnST...42.3910L. doi:10.1021/es0871199. PMID 18589943.

- Phoenix, Chris (March 2005) Nanotechnology: Developing Molecular Manufacturing Archived 2005-09-01 at the Wayback Machine. crnano.org

- "Some papers by K. Eric Drexler". imm.org. Archived from the original on 2006-04-11.

- Carlo Montemagno, Ph.D. Archived 2011-09-17 at the Wayback Machine California NanoSystems Institute

- "Cover Story – Nanotechnology". Chemical and Engineering News. 81 (48): 37–42. December 1, 2003.

- Regan, BC; Aloni, S; Jensen, K; Ritchie, RO; Zettl, A (2005). "Nanocrystal-powered nanomotor" (PDF). Nano Letters. 5 (9): 1730–3. Bibcode:2005NanoL...5.1730R. doi:10.1021/nl0510659. PMID 16159214. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-10.

- Regan, B. C.; Aloni, S.; Jensen, K.; Zettl, A. (2005). "Surface-tension-driven nanoelectromechanical relaxation oscillator" (PDF). Applied Physics Letters. 86 (12): 123119. Bibcode:2005ApPhL..86l3119R. doi:10.1063/1.1887827. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-05-26.

- Goodman, R.P.; Schaap, I.A.T.; Tardin, C.F.; Erben, C.M.; Berry, R.M.; Schmidt, C.F.; Turberfield, A.J. (9 December 2005). "Rapid chiral assembly of rigid DNA building blocks for molecular nanofabrication". Science. 310 (5754): 1661–1665. Bibcode:2005Sci...310.1661G. doi:10.1126/science.1120367. PMID 16339440. S2CID 13678773.

- "Wireless Nanocrystals Efficiently Radiate Visible Light". Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Narayan, R. J.; Kumta, P. N.; Sfeir, Ch.; Lee, D-H; Choi, D.; Olton, D. (2004). "Nanostructured Ceramics in Medical Devices: Applications and Prospects". JOM. 56 (10): 38–43. Bibcode:2004JOM....56j..38N. doi:10.1007/s11837-004-0289-x.

- Cho, Hongsik; Pinkhassik, Eugene; David, Valentin; Stuart, John; Hasty, Karen (31 May 2015). "Detection of early cartilage damage using targeted nanosomes in a post-traumatic osteoarthritis mouse model". Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine. 11 (4): 939–946. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2015.01.011. PMID 25680539.

- Kerativitayanan, Punyavee; Carrow, James K.; Gaharwar, Akhilesh K. (May 2015). "Nanomaterials for Engineering Stem Cell Responses". Advanced Healthcare Materials. 4 (11): 1600–27. doi:10.1002/adhm.201500272. PMID 26010739.

- Gaharwar, A.K.; Sant, S.; Hancock, M.J.; Hacking, S.A., eds. (2013). Nanomaterials in tissue engineering : fabrication and applications. Oxford: Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85709-596-1.

- Gaharwar, A.K.; Peppas, N.A.; Khademhosseini, A. (March 2014). "Nanocomposite hydrogels for biomedical applications". Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 111 (3): 441–53. doi:10.1002/bit.25160. PMC 3924876. PMID 24264728.

- Levins, Christopher G.; Schafmeister, Christian E. (2006). "The Synthesis of Curved and Linear Structures from a Minimal Set of Monomers". ChemInform. 37 (5). doi:10.1002/chin.200605222.

- "Applications/Products". National Nanotechnology Initiative. Archived from the original on 2010-11-20. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2007". Nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 2011-08-05. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- Das S, Gates AJ, Abdu HA, Rose GS, Picconatto CA, Ellenbogen JC (2007). "Designs for Ultra-Tiny, Special-Purpose Nanoelectronic Circuits". IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I. 54 (11): 2528–2540. doi:10.1109/TCSI.2007.907864.

- Mashaghi, S.; Jadidi, T.; Koenderink, G.; Mashaghi, A. (2013). "Lipid Nanotechnology". Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013 (14): 4242–4282. doi:10.3390/ijms14024242. PMC 3588097. PMID 23429269.

- Hogan, C. Michael (2010) "Virus" Archived 2011-10-16 at the Wayback Machine in Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. eds. S. Draggan and C. Cleveland

- Kubik T, Bogunia-Kubik K, Sugisaka M (2005). "Nanotechnology on duty in medical applications". Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 6 (1): 17–33. doi:10.2174/1389201053167248. PMID 15727553.

- Leary, SP; Liu, CY; Apuzzo, ML (2006). "Toward the Emergence of Nanoneurosurgery: Part III-Nanomedicine: Targeted Nanotherapy, Nanosurgery, and Progress Toward the Realization of Nanoneurosurgery". Neurosurgery. 58 (6): 1009–1026. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000217016.79256.16. PMID 16723880.

- Cavalcanti, A.; Shirinzadeh, B.; Freitas, R.; Kretly, L. (2007). "Medical Nanorobot Architecture Based on Nanobioelectronics". Recent Patents on Nanotechnology. 1 (1): 1–10. doi:10.2174/187221007779814745. PMID 19076015. S2CID 9807497.

- Boukallel M, Gauthier M, Dauge M, Piat E, Abadie J (2007). "Smart microrobots for mechanical cell characterization and cell convoying" (PDF). IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 54 (8): 1536–40. doi:10.1109/TBME.2007.891171. PMID 17694877.

- "International Perspective on Government Nanotechnology Funding in 2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-31.

- Lapshin, R. V. (2004). "Feature-oriented scanning methodology for probe microscopy and nanotechnology" (PDF). Nanotechnology. 15 (9): 1135–1151. Bibcode:2004Nanot..15.1135L. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/15/9/006. Archived from the original on 2013-09-09.

- Lapshin, R. V. (2011). "Feature-oriented scanning probe microscopy". In H. S. Nalwa (ed.). Encyclopedia of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology (PDF). 14. USA: American Scientific Publishers. pp. 105–115. ISBN 978-1-58883-163-7. Archived from the original on 2013-09-09.

- Kafshgari, MH; Voelcker, NH; Harding, FJ (2015). "Applications of zero-valent silicon nanostructures in biomedicine". Nanomedicine (Lond). 10 (16): 2553–71. doi:10.2217/nnm.15.91. PMID 26295171.

- Rajan, Reshmy; Jose, Shoma; Mukund, V. P. Biju; Vasudevan, Deepa T. (2011-01-01). "Transferosomes – A vesicular transdermal delivery system for enhanced drug permeation". Journal of Advanced Pharmaceutical Technology & Research. 2 (3): 138–143. doi:10.4103/2231-4040.85524. PMC 3217704. PMID 22171309.

- Apply nanotech to up industrial, agri output Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine, The Daily Star (Bangladesh), 17 April 2012.

- Kurtoglu M. E.; Longenbach T.; Reddington P.; Gogotsi Y. (2011). "Effect of Calcination Temperature and Environment on Photocatalytic and Mechanical Properties of Ultrathin Sol–Gel Titanium Dioxide Films". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 94 (4): 1101–1108. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2010.04218.x.

- "Nanotechnology Consumer Products". nnin.org. 2010. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- Nano in computing and electronics Archived 2011-11-14 at the Wayback Machine at NanoandMe.org

- Mayer, B.; Janker, L.; Loitsch, B.; Treu, J.; Kostenbader, T.; Lichtmannecker, S.; Reichert, T.; Morkötter, S.; Kaniber, M.; Abstreiter, G.; Gies, C.; Koblmüller, G.; Finley, J. J. (2015). "Monolithically Integrated High-β Nanowire Lasers on Silicon". Nano Letters. 16 (1): 152–156. Bibcode:2016NanoL..16..152M. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b03404. PMID 26618638.

- Nano in medicine Archived 2011-11-14 at the Wayback Machine at NanoandMe.org

- Nano in transport Archived 2011-10-29 at the Wayback Machine at NanoandMe.org

- Catalytic Converter at Wikipedia.org

- How Catalytic Converters Work Archived 2014-12-10 at the Wayback Machine at howstuffworks.com

- Nanotechnology to provide cleaner diesel engines Archived 2014-12-14 at the Wayback Machine. RDmag.com. September 2014

- Cassidy, John W. (2014). "Nanotechnology in the Regeneration of Complex Tissues". Bone and Tissue Regeneration Insights. 5: 25–35. doi:10.4137/BTRI.S12331. PMC 4471123. PMID 26097381.

- Cassidy, J. W.; Roberts, J. N.; Smith, C. A.; Robertson, M.; White, K.; Biggs, M. J.; Oreffo, R. O. C.; Dalby, M. J. (2014). "Osteogenic lineage restriction by osteoprogenitors cultured on nanometric grooved surfaces: The role of focal adhesion maturation". Acta Biomaterialia. 10 (2): 651–660. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2013.11.008. PMC 3907683. PMID 24252447. Archived from the original on 2017-08-30.

- Amir, Y.; Ben-Ishay, E.; Levner, D.; Ittah, S.; Abu-Horowitz, A.; Bachelet, I. (2014). "Universal computing by DNA origami robots in a living animal". Nature Nanotechnology. 9 (5): 353–357. Bibcode:2014NatNa...9..353A. doi:10.1038/nnano.2014.58. PMC 4012984. PMID 24705510.

- "History: 2010s". SK Hynix. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "16/12nm Technology". TSMC. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- "Samsung Mass Producing 128Gb 3-bit MLC NAND Flash". Tom's Hardware. 11 April 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- "7nm Technology". TSMC. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Shilov, Anton. "Samsung Completes Development of 5nm EUV Process Technology". www.anandtech.com. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- Armasu, Lucian (11 January 2019), "Samsung Plans Mass Production of 3nm GAAFET Chips in 2021", www.tomshardware.com

- "CDC – Nanotechnology – NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. June 15, 2012. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved 2012-08-24.

- "CDC – NIOSH Publications and Products – Filling the Knowledge Gaps for Safe Nanotechnology in the Workplace". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. November 7, 2012. doi:10.26616/NIOSHPUB2013101. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-08. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Lubick, N; Betts, Kellyn (2008). "Silver socks have cloudy lining". Environmental Science & Technology. 42 (11): 3910. Bibcode:2008EnST...42.3910L. doi:10.1021/es0871199. PMID 18589943.

- Murray R.G.E. (1993) Advances in Bacterial Paracrystalline Surface Layers. T. J. Beveridge, S. F. Koval (Eds.). Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0-306-44582-8. pp. 3–9.

- Harthorn, Barbara Herr (January 23, 2009) "People in the US and the UK show strong similarities in their attitudes toward nanotechnologies" Archived 2011-08-23 at the Wayback Machine. Nanotechnology Today.

- Testimony of David Rejeski for U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation Archived 2008-04-08 at the Wayback Machine Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies. Retrieved on 2008-3-7.

- DelVecchio, Rick (November 24, 2006) Berkeley considering need for nano safety Archived 2008-04-09 at the Wayback Machine. sfgate.com

- Bray, Hiawatha (January 26, 2007) Cambridge considers nanotech curbs – City may mimic Berkeley bylaws Archived 2008-05-11 at the Wayback Machine. boston.com

- Recommendations for a Municipal Health & Safety Policy for Nanomaterials: A Report to the Cambridge City Manager Archived 2011-07-14 at the Wayback Machine. nanolawreport.com. July 2008.

- Byrne, J. D.; Baugh, J. A. (2008). "The significance of nanoparticles in particle-induced pulmonary fibrosis". McGill Journal of Medicine : MJM : An International Forum for the Advancement of Medical Sciences by Students. 11 (1): 43–50. PMC 2322933. PMID 18523535.

- Elder, A. (2006). Tiny Inhaled Particles Take Easy Route from Nose to Brain. urmc.rochester.edu Archived September 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Wu, J; Liu, W; Xue, C; Zhou, S; Lan, F; Bi, L; Xu, H; Yang, X; Zeng, FD (2009). "Toxicity and penetration of TiO2 nanoparticles in hairless mice and porcine skin after subchronic dermal exposure". Toxicology Letters. 191 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.05.020. PMID 19501137.

- Jonaitis, TS; Card, JW; Magnuson, B (2010). "Concerns regarding nano-sized titanium dioxide dermal penetration and toxicity study". Toxicology Letters. 192 (2): 268–9. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.10.007. PMID 19836437.

- Schneider, Andrew (March 24, 2010) "Amid Nanotech's Dazzling Promise, Health Risks Grow" Archived 2010-03-26 at the Wayback Machine. AOL News

- Weiss, R. (2008). Effects of Nanotubes May Lead to Cancer, Study Says. Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Paull, J. & Lyons, K. (2008). "Nanotechnology: The Next Challenge for Organics" (PDF). Journal of Organic Systems. 3: 3–22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-18.

- Smith, Rebecca (August 19, 2009). "Nanoparticles used in paint could kill, research suggests". Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on March 15, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- Nanofibres 'may pose health risk' Archived 2012-08-25 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. 2012-08-24

- Schinwald, A.; Murphy, F. A.; Prina-Mello, A.; Poland, C. A.; Byrne, F.; Movia, D.; Glass, J. R.; Dickerson, J. C.; Schultz, D. A.; Jeffree, C. E.; MacNee, W.; Donaldson, K. (2012). "The Threshold Length for Fiber-Induced Acute Pleural Inflammation: Shedding Light on the Early Events in Asbestos-Induced Mesothelioma". Toxicological Sciences. 128 (2): 461–470. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfs171. PMID 22584686.

- Is Chronic Inflammation the Key to Unlocking the Mysteries of Cancer? Archived 2012-11-04 at the Wayback Machine Scientific American. 2008-11-09

- Kevin Rollins (Nems Mems Works, LLC). "Nanobiotechnology Regulation: A Proposal for Self-Regulation with Limited Oversight". Volume 6 – Issue 2. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- Bowman D, Hodge G (2006). "Nanotechnology: Mapping the Wild Regulatory Frontier". Futures. 38 (9): 1060–1073. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2006.02.017.

- Davies, J. C. (2008). Nanotechnology Oversight: An Agenda for the Next Administration Archived 2008-11-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- Rowe, G. (2005). "Difficulties in evaluating public engagement initiatives: Reflections on an evaluation of the UK GM Nation? Public debate about transgenic crops". Public Understanding of Science (Submitted manuscript). 14 (4): 331–352. doi:10.1177/0963662505056611.

- Maynard, A.Testimony by Dr. Andrew Maynard for the U.S. House Committee on Science and Technology. (2008-4-16). Retrieved on 2008-11-24. Archived May 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Faunce, T.; Murray, K.; Nasu, H.; Bowman, D. (2008). "Sunscreen Safety: The Precautionary Principle, the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration and Nanoparticles in Sunscreens". NanoEthics. 2 (3): 231–240. doi:10.1007/s11569-008-0041-z.

- Thomas Faunce; Katherine Murray; Hitoshi Nasu & Diana Bowman (24 July 2008). "Sunscreen Safety: The Precautionary Principle, The Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration and Nanoparticles in Sunscreens" (PDF). Springer Science + Business Media B.V. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nanotechnology. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Nanotechnology |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Nanotechnology |

| At Wikiversity, you can learn more and teach others about Nanotechnology at the Department of Nanotechnology |

- Nanotechnology at Curlie

- What is Nanotechnology? (A Vega/BBC/OU Video Discussion).