Nanoelectronics

Nanoelectronics refers to the use of nanotechnology in electronic components. The term covers a diverse set of devices and materials, with the common characteristic that they are so small that inter-atomic interactions and quantum mechanical properties need to be studied extensively. Some of these candidates include: hybrid molecular/semiconductor electronics, one-dimensional nanotubes/nanowires (e.g. silicon nanowires or carbon nanotubes) or advanced molecular electronics.

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Nanoelectronics |

|---|

| Single-molecule electronics |

| Solid-state nanoelectronics |

| Related approaches |

|

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Nanotechnology |

|---|

| Impact and applications |

| Nanomaterials |

| Molecular self-assembly |

| Nanoelectronics |

| Nanometrology |

|

| Molecular nanotechnology |

|

Nanoelectronic devices have critical dimensions with a size range between 1 nm and 100 nm.[1] Recent silicon MOSFET (metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor, or MOS transistor) technology generations are already within this regime, including 22 nanometer CMOS (complementary MOS) nodes and succeeding 14 nm, 10 nm and 7 nm FinFET (fin field-effect transistor) generations. Nanoelectronics are sometimes considered as disruptive technology because present candidates are significantly different from traditional transistors.

Fundamental concepts

In 1965, Gordon Moore observed that silicon transistors were undergoing a continual process of scaling downward, an observation which was later codified as Moore's law. Since his observation, transistor minimum feature sizes have decreased from 10 micrometers to the 10 nm range as of 2019. Note that the technology node doesn't directly represent the minimum feature size. The field of nanoelectronics aims to enable the continued realization of this law by using new methods and materials to build electronic devices with feature sizes on the nanoscale.

Mechanical issues

The volume of an object decreases as the third power of its linear dimensions, but the surface area only decreases as its second power. This somewhat subtle and unavoidable principle has huge ramifications. For example, the power of a drill (or any other machine) is proportional to the volume, while the friction of the drill's bearings and gears is proportional to their surface area. For a normal-sized drill, the power of the device is enough to handily overcome any friction. However, scaling its length down by a factor of 1000, for example, decreases its power by 10003 (a factor of a billion) while reducing the friction by only 10002 (a factor of only a million). Proportionally it has 1000 times less power per unit friction than the original drill. If the original friction-to-power ratio was, say, 1%, that implies the smaller drill will have 10 times as much friction as power; the drill is useless.

For this reason, while super-miniature electronic integrated circuits are fully functional, the same technology cannot be used to make working mechanical devices beyond the scales where frictional forces start to exceed the available power. So even though you may see microphotographs of delicately etched silicon gears, such devices are currently little more than curiosities with limited real world applications, for example, in moving mirrors and shutters.[2] Surface tension increases in much the same way, thus magnifying the tendency for very small objects to stick together. This could possibly make any kind of "micro factory" impractical: even if robotic arms and hands could be scaled down, anything they pick up will tend to be impossible to put down. The above being said, molecular evolution has resulted in working cilia, flagella, muscle fibers and rotary motors in aqueous environments, all on the nanoscale. These machines exploit the increased frictional forces found at the micro or nanoscale. Unlike a paddle or a propeller which depends on normal frictional forces (the frictional forces perpendicular to the surface) to achieve propulsion, cilia develop motion from the exaggerated drag or laminar forces (frictional forces parallel to the surface) present at micro and nano dimensions. To build meaningful "machines" at the nanoscale, the relevant forces need to be considered. We are faced with the development and design of intrinsically pertinent machines rather than the simple reproductions of macroscopic ones.

All scaling issues therefore need to be assessed thoroughly when evaluating nanotechnology for practical applications.

Approaches

Nanofabrication

For example, electron transistors, which involve transistor operation based on a single electron. Nanoelectromechanical systems also fall under this category. Nanofabrication can be used to construct ultradense parallel arrays of nanowires, as an alternative to synthesizing nanowires individually.[3][4] Of particular prominence in this field, Silicon nanowires are being increasingly studied towards diverse applications in nanoelectronics, energy conversion and storage. Such SiNWs can be fabricated by thermal oxidation in large quantities to yield nanowires with controllable thickness.

Nanomaterials electronics

Besides being small and allowing more transistors to be packed into a single chip, the uniform and symmetrical structure of nanowires and/or nanotubes allows a higher electron mobility (faster electron movement in the material), a higher dielectric constant (faster frequency), and a symmetrical electron/hole characteristic.[5]

Also, nanoparticles can be used as quantum dots.

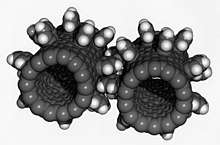

Molecular electronics

Single molecule devices are another possibility. These schemes would make heavy use of molecular self-assembly, designing the device components to construct a larger structure or even a complete system on their own. This can be very useful for reconfigurable computing, and may even completely replace present FPGA technology.

Molecular electronics[6] is a new technology which is still in its infancy, but also brings hope for truly atomic scale electronic systems in the future. One of the more promising applications of molecular electronics was proposed by the IBM researcher Ari Aviram and the theoretical chemist Mark Ratner in their 1974 and 1988 papers Molecules for Memory, Logic and Amplification, (see Unimolecular rectifier).[7][8]

This is one of many possible ways in which a molecular level diode / transistor might be synthesized by organic chemistry. A model system was proposed with a spiro carbon structure giving a molecular diode about half a nanometre across which could be connected by polythiophene molecular wires. Theoretical calculations showed the design to be sound in principle and there is still hope that such a system can be made to work.

Other approaches

Nanoionics studies the transport of ions rather than electrons in nanoscale systems.

Nanophotonics studies the behavior of light on the nanoscale, and has the goal of developing devices that take advantage of this behavior.

History

In 1960, Egyptian engineer Mohamed Atalla and Korean engineer Dawon Kahng at Bell Labs fabricated the first MOSFET (metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor) with a gate oxide thickness of 100 nm, along with a gate length of 20 µm.[9] In 1962, Atalla and Kahng fabricated a nanolayer-base metal–semiconductor junction transistor that used gold (Au) thin films with a thickness of 10 nm.[10] In 1987, Iranian engineer Bijan Davari led an IBM research team that demonstrated the first MOSFET with a 10 nm gate oxide thickness, using tungsten-gate technology.[11]

Multi-gate MOSFETs enabled scaling below 20 nm gate length, starting with the FinFET (fin field-effect transistor), a three-dimensional, non-planar, double-gate MOSFET.[12] The FinFET originates from the DELTA transistor developed by Hitachi Central Research Laboratory's Digh Hisamoto, Toru Kaga, Yoshifumi Kawamoto and Eiji Takeda in 1989.[13][14][15][16] In 1997, DARPA awarded a contract to a research group at UC Berkeley to develop a deep sub-micron DELTA transistor.[16] The group consisted of Hisamoto along with TSMC's Chenming Hu and other international researchers including Tsu-Jae King Liu, Jeffrey Bokor, Hideki Takeuchi, K. Asano, Jakub Kedziersk, Xuejue Huang, Leland Chang, Nick Lindert, Shibly Ahmed and Cyrus Tabery. The team successfully fabricated FinFET devices down to a 17 nm process in 1998, and then 15 nm in 2001. In 2002, a team including Yu, Chang, Ahmed, Hu, Liu, Bokor and Tabery fabricated a 10 nm FinFET device.[12]

In 1999, a CMOS (complementary MOS) transistor developed at the Laboratory for Electronics and Information Technology in Grenoble, France, tested the limits of the principles of the MOSFET transistor with a diameter of 18 nm (approximately 70 atoms placed side by side). It enabled the theoretical integration of seven billion junctions on a €1 coin. However, the CMOS transistor was not a simple research experiment to study how CMOS technology functions, but rather a demonstration of how this technology functions now that we ourselves are getting ever closer to working on a molecular scale. According to Jean-Baptiste Waldner in 2007, it would be impossible to master the coordinated assembly of a large number of these transistors on a circuit and it would also be impossible to create this on an industrial level.[17]

In 2006, a team of Korean researchers from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) and the National Nano Fab Center developed a 3 nm MOSFET, the world's smallest nanoelectronic device. It was based on gate-all-around (GAA) FinFET technology.[18][19]

Commercial production of nanoelectronic semiconductor devices began in the 2010s. In 2013, SK Hynix began commercial mass-production of a 16 nm process,[20] TSMC began production of a 16 nm FinFET process,[21] and Samsung Electronics began production of a 10 nm class process.[22] TSMC began production of a 7 nm process in 2017,[23] and Samsung began production of a 5 nm process in 2018.[24] In 2017, TSMC announced plans for the commercial production of a 3 nm process by 2022.[25] In 2019, Samsung announced plans for a 3 nm GAAFET (gate-all-around FET) process by 2021.[26]

Nanoelectronic devices

Current high-technology production processes are based on traditional top down strategies, where nanotechnology has already been introduced silently. The critical length scale of integrated circuits is already at the nanoscale (50 nm and below) regarding the gate length of transistors in CPUs or DRAM devices.

Computers

Nanoelectronics holds the promise of making computer processors more powerful than are possible with conventional semiconductor fabrication techniques. A number of approaches are currently being researched, including new forms of nanolithography, as well as the use of nanomaterials such as nanowires or small molecules in place of traditional CMOS components. Field effect transistors have been made using both semiconducting carbon nanotubes[27] and with heterostructured semiconductor nanowires (SiNWs).[28]

Memory storage

Electronic memory designs in the past have largely relied on the formation of transistors. However, research into crossbar switch based electronics have offered an alternative using reconfigurable interconnections between vertical and horizontal wiring arrays to create ultra high density memories. Two leaders in this area are Nantero which has developed a carbon nanotube based crossbar memory called Nano-RAM and Hewlett-Packard which has proposed the use of memristor material as a future replacement of Flash memory.

An example of such novel devices is based on spintronics. The dependence of the resistance of a material (due to the spin of the electrons) on an external field is called magnetoresistance. This effect can be significantly amplified (GMR - Giant Magneto-Resistance) for nanosized objects, for example when two ferromagnetic layers are separated by a nonmagnetic layer, which is several nanometers thick (e.g. Co-Cu-Co). The GMR effect has led to a strong increase in the data storage density of hard disks and made the gigabyte range possible. The so-called tunneling magnetoresistance (TMR) is very similar to GMR and based on the spin dependent tunneling of electrons through adjacent ferromagnetic layers. Both GMR and TMR effects can be used to create a non-volatile main memory for computers, such as the so-called magnetic random access memory or MRAM.

Commercial production of nanoelectronic memory began in the 2010s. In 2013, SK Hynix began mass-production of 16 nm NAND flash memory,[20] and Samsung Electronics began production of 10 nm multi-level cell (MLC) NAND flash memory.[22] In 2017, TSMC began production of SRAM memory using a 7 nm process.[23]

Novel optoelectronic devices

In the modern communication technology traditional analog electrical devices are increasingly replaced by optical or optoelectronic devices due to their enormous bandwidth and capacity, respectively. Two promising examples are photonic crystals and quantum dots. Photonic crystals are materials with a periodic variation in the refractive index with a lattice constant that is half the wavelength of the light used. They offer a selectable band gap for the propagation of a certain wavelength, thus they resemble a semiconductor, but for light or photons instead of electrons. Quantum dots are nanoscaled objects, which can be used, among many other things, for the construction of lasers. The advantage of a quantum dot laser over the traditional semiconductor laser is that their emitted wavelength depends on the diameter of the dot. Quantum dot lasers are cheaper and offer a higher beam quality than conventional laser diodes.

Displays

The production of displays with low energy consumption might be accomplished using carbon nanotubes (CNT) and/or Silicon nanowires. Such nanostructures are electrically conductive and due to their small diameter of several nanometers, they can be used as field emitters with extremely high efficiency for field emission displays (FED). The principle of operation resembles that of the cathode ray tube, but on a much smaller length scale.

Quantum computers

Entirely new approaches for computing exploit the laws of quantum mechanics for novel quantum computers, which enable the use of fast quantum algorithms. The Quantum computer has quantum bit memory space termed "Qubit" for several computations at the same time. This facility may improve the performance of the older systems.

Radios

Nanoradios have been developed structured around carbon nanotubes.[29]

Energy production

Research is ongoing to use nanowires and other nanostructured materials with the hope to create cheaper and more efficient solar cells than are possible with conventional planar silicon solar cells.[30] It is believed that the invention of more efficient solar energy would have a great effect on satisfying global energy needs.

There is also research into energy production for devices that would operate in vivo, called bio-nano generators. A bio-nano generator is a nanoscale electrochemical device, like a fuel cell or galvanic cell, but drawing power from blood glucose in a living body, much the same as how the body generates energy from food. To achieve the effect, an enzyme is used that is capable of stripping glucose of its electrons, freeing them for use in electrical devices. The average person's body could, theoretically, generate 100 watts of electricity (about 2000 food calories per day) using a bio-nano generator.[31] However, this estimate is only true if all food was converted to electricity, and the human body needs some energy consistently, so possible power generated is likely much lower. The electricity generated by such a device could power devices embedded in the body (such as pacemakers), or sugar-fed nanorobots. Much of the research done on bio-nano generators is still experimental, with Panasonic's Nanotechnology Research Laboratory among those at the forefront.

Medical diagnostics

There is great interest in constructing nanoelectronic devices[32][33][34] that could detect the concentrations of biomolecules in real time for use as medical diagnostics,[35] thus falling into the category of nanomedicine.[36] A parallel line of research seeks to create nanoelectronic devices which could interact with single cells for use in basic biological research.[37] These devices are called nanosensors. Such miniaturization on nanoelectronics towards in vivo proteomic sensing should enable new approaches for health monitoring, surveillance, and defense technology.[38][39][40]

References

- Beaumont, Steven P. (September 1996). "III–V Nanoelectronics". Microelectronic Engineering. 32 (1): 283–295. doi:10.1016/0167-9317(95)00367-3. ISSN 0167-9317.

- "MEMS Overview". Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- Melosh, N.; Boukai, Abram; Diana, Frederic; Gerardot, Brian; Badolato, Antonio; Petroff, Pierre; Heath, James R. (2003). "Ultrahigh density nanowire lattices and circuits". Science. 300 (5616): 112–5. Bibcode:2003Sci...300..112M. doi:10.1126/science.1081940. PMID 12637672.

- Das, S.; Gates, A.J.; Abdu, H.A.; Rose, G.S.; Picconatto, C.A.; Ellenbogen, J.C. (2007). "Designs for Ultra-Tiny, Special-Purpose Nanoelectronic Circuits". IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I. 54 (11): 11. doi:10.1109/TCSI.2007.907864.

- Goicoechea, J.; Zamarreñoa, C.R.; Matiasa, I.R.; Arregui, F.J. (2007). "Minimizing the photobleaching of self-assembled multilayers for sensor applications". Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 126 (1): 41–47. doi:10.1016/j.snb.2006.10.037.

- Petty, M.C.; Bryce, M.R.; Bloor, D. (1995). An Introduction to Molecular Electronics. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 978-0-19-521156-6.

- Aviram, A.; Ratner, M. A. (1974). "Molecular Rectifier". Chemical Physics Letters. 29 (2): 277–283. Bibcode:1974CPL....29..277A. doi:10.1016/0009-2614(74)85031-1.

- Aviram, A. (1988). "Molecules for memory, logic, and amplification". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 110 (17): 5687–5692. doi:10.1021/ja00225a017.

- Sze, Simon M. (2002). Semiconductor Devices: Physics and Technology (PDF) (2nd ed.). Wiley. p. 4. ISBN 0-471-33372-7.

- Pasa, André Avelino (2010). "Chapter 13: Metal Nanolayer-Base Transistor". Handbook of Nanophysics: Nanoelectronics and Nanophotonics. CRC Press. pp. 13–1, 13–4. ISBN 9781420075519.

- Davari, Bijan; Ting, Chung-Yu; Ahn, Kie Y.; Basavaiah, S.; Hu, Chao-Kun; Taur, Yuan; Wordeman, Matthew R.; Aboelfotoh, O.; Krusin-Elbaum, L.; Joshi, Rajiv V.; Polcari, Michael R. (1987). "Submicron Tungsten Gate MOSFET with 10 nm Gate Oxide". 1987 Symposium on VLSI Technology. Digest of Technical Papers: 61–62.

- Tsu‐Jae King, Liu (June 11, 2012). "FinFET: History, Fundamentals and Future". University of California, Berkeley. Symposium on VLSI Technology Short Course. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- Colinge, J.P. (2008). FinFETs and Other Multi-Gate Transistors. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 11. ISBN 9780387717517.

- Hisamoto, D.; Kaga, T.; Kawamoto, Y.; Takeda, E. (December 1989). "A fully depleted lean-channel transistor (DELTA)-a novel vertical ultra thin SOI MOSFET". International Technical Digest on Electron Devices Meeting: 833–836. doi:10.1109/IEDM.1989.74182.

- "IEEE Andrew S. Grove Award Recipients". IEEE Andrew S. Grove Award. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- "The Breakthrough Advantage for FPGAs with Tri-Gate Technology" (PDF). Intel. 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Waldner, Jean-Baptiste (2007). Nanocomputers and Swarm Intelligence. London: ISTE. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-84704-002-2.

- "Still Room at the Bottom (nanometer transistor developed by Yang-kyu Choi from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology)", Nanoparticle News, 1 April 2006, archived from the original on 6 November 2012, retrieved 6 July 2019

- Lee, Hyunjin; et al. (2006), "Sub-5nm All-Around Gate FinFET for Ultimate Scaling", Symposium on VLSI Technology, 2006: 58–59, doi:10.1109/VLSIT.2006.1705215, hdl:10203/698, ISBN 978-1-4244-0005-8

- "History: 2010s". SK Hynix. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "16/12nm Technology". TSMC. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- "Samsung Mass Producing 128Gb 3-bit MLC NAND Flash". Tom's Hardware. 11 April 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- "7nm Technology". TSMC. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Shilov, Anton. "Samsung Completes Development of 5nm EUV Process Technology". www.anandtech.com. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- Patterson, Alan (2 Oct 2017), "TSMC Aims to Build World's First 3-nm Fab", www.eetimes.com

- Armasu, Lucian (11 January 2019), "Samsung Plans Mass Production of 3nm GAAFET Chips in 2021", www.tomshardware.com

- Postma, Henk W. Ch.; Teepen, Tijs; Yao, Zhen; Grifoni, Milena; Dekker, Cees (2001). "Carbon nanotube single-electron transistors at room temperature". Science. 293 (5527): 76–79. Bibcode:2001Sci...293...76P. doi:10.1126/science.1061797. PMID 11441175.

- Xiang, Jie; Lu, Wei; Hu, Yongjie; Wu, Yue; Yan Hao; Lieber, Charles M. (2006). "Ge/Si nanowire heterostructures as highperformance field-effect transistors". Nature. 441 (7092): 489–493. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..489X. doi:10.1038/nature04796. PMID 16724062.

- Jensen, K.; Weldon, J.; Garcia, H.; Zettl A. (2007). "Nanotube Radio". Nano Lett. 7 (11): 3508–3511. Bibcode:2007NanoL...7.3508J. doi:10.1021/nl0721113. PMID 17973438.

- Tian, Bozhi; Zheng, Xiaolin; Kempa, Thomas J.; Fang, Ying; Yu, Nanfang; Yu, Guihua; Huang, Jinlin; Lieber, Charles M. (2007). "Coaxial silicon nanowires as solar cells and nanoelectronic power sources". Nature. 449 (7164): 885–889. Bibcode:2007Natur.449..885T. doi:10.1038/nature06181. PMID 17943126.

- "Power from blood could lead to 'human batteries'". Sydney Morning Herald. August 4, 2003. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- LaVan, D.A.; McGuire, Terry & Langer, Robert (2003). "Small-scale systems for in vivo drug delivery". Nat. Biotechnol. 21 (10): 1184–1191. doi:10.1038/nbt876. PMID 14520404.

- Grace, D. (2008). "Special Feature: Emerging Technologies". Medical Product Manufacturing News. 12: 22–23. Archived from the original on 2008-06-12.

- Saito, S. (1997). "Carbon Nanotubes for Next-Generation Electronics Devices". Science. 278 (5335): 77–78. doi:10.1126/science.278.5335.77.

- Cavalcanti, A.; Shirinzadeh, B.; Freitas Jr, Robert A. & Hogg, Tad (2008). "Nanorobot architecture for medical target identification". Nanotechnology. 19 (1): 015103(15pp). Bibcode:2008Nanot..19a5103C. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/19/01/015103.

- Cheng, Mark Ming-Cheng; Cuda, Giovanni; Bunimovich, Yuri L; Gaspari, Marco; Heath, James R; Hill, Haley D; Mirkin,Chad A; Nijdam, A Jasper; Terracciano, Rosa; Thundat, Thomas; Ferrari, Mauro (2006). "Nanotechnologies for biomolecular detection and medical diagnostics". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 10 (1): 11–19. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.01.006. PMID 16418011.

- Patolsky, F.; Timko, B.P.; Yu, G.; Fang, Y.; Greytak, A.B.; Zheng, G.; Lieber, C.M. (2006). "Detection, stimulation, and inhibition of neuronal signals with high-density nanowire transistor arrays". Science. 313 (5790): 1100–1104. Bibcode:2006Sci...313.1100P. doi:10.1126/science.1128640. PMID 16931757.

- Frist, W.H. (2005). "Health care in the 21st century". N. Engl. J. Med. 352 (3): 267–272. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa045011. PMID 15659726.

- Cavalcanti, A.; Shirinzadeh, B.; Zhang, M. & Kretly, L.C. (2008). "Nanorobot Hardware Architecture for Medical Defense" (PDF). Sensors. 8 (5): 2932–2958. doi:10.3390/s8052932. PMC 3675524. PMID 27879858.

- Couvreur, P. & Vauthier, C. (2006). "Nanotechnology: intelligent design to treat complex disease". Pharm. Res. 23 (7): 1417–1450. doi:10.1007/s11095-006-0284-8. PMID 16779701.

Further reading

- Bennett, Herbert S.; Andres, Howard; Pellegrino, Joan; Kwok, Winnie; Fabricius, Norbert; Chapin, J. Thomas (March–April 2009). "Priorities for Standards and Measurements to Accelerate Innovations in Nano-Electrotechnologies: Analysis of the NIST-Energetics-IEC TC 113 Survey" (PDF). Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. 114 (2): 99–135. doi:10.6028/jres.114.008. PMC 4648624. PMID 27504216. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-05.

- Despotuli, Alexander; Andreeva, Alexandra (August–October 2009). "A Short Review on Deep-Sub-Voltage Nanoelectronics and Related Technologies". International Journal of Nanoscience. 8 (4–5): 389–402. Bibcode:2009IJN....08..389D. doi:10.1142/S0219581X09006328.

- Veendrick, H.J.M. (2011). Bits on Chips. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-61627-947-9.https://openlibrary.org/works/OL15759799W/Bits_on_Chips/

- Online course on Fundamentals of Electronics by Supriyo Datta (2008)

- Lessons from Nanoelectronics: A New Perspective on Transport(In 2 Parts)(2nd Edition) by Supriyo Datta (2018)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nanoelectronics. |

- IEEE Silicon Nanoelectronics Workshop

- Virtual Institute of Spin Electronics

- Site on electronics of Single Walled Carbon nanotube at nanoscale - nanoelectronics

- Site on Nano Electronics and Advanced VLSI Research

- Website of the nanoelectronics unit of the European Commission, DG INFSO

- Nanoelectronics at UnderstandingNano Web site

- Nanoelectronics - PhysOrg