Nucleic acid double helix

In molecular biology, the term double helix[1] refers to the structure formed by double-stranded molecules of nucleic acids such as DNA. The double helical structure of a nucleic acid complex arises as a consequence of its secondary structure, and is a fundamental component in determining its tertiary structure. The term entered popular culture with the publication in 1968 of The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA by James Watson.

The DNA double helix biopolymer of nucleic acid is held together by nucleotides which base pair together.[2] In B-DNA, the most common double helical structure found in nature, the double helix is right-handed with about 10–10.5 base pairs per turn.[3] The double helix structure of DNA contains a major groove and minor groove. In B-DNA the major groove is wider than the minor groove.[2] Given the difference in widths of the major groove and minor groove, many proteins which bind to B-DNA do so through the wider major groove.[4]

History

The double-helix model of DNA structure was first published in the journal Nature by James Watson and Francis Crick in 1953,[5] (X,Y,Z coordinates in 1954[6]) based on the work of Rosalind Franklin, including the crucial X-ray diffraction image of DNA labeled as "Photo 51", from 1952,[7] followed by her more clarified DNA image with Raymond Gosling,[8][9] Maurice Wilkins, Alexander Stokes, and Herbert Wilson,[10] and base-pairing chemical and biochemical information by Erwin Chargaff.[11][12][13][14][15][16] The prior model was triple-stranded DNA.[17]

The realization that the structure of DNA is that of a double-helix elucidated the mechanism of base pairing by which genetic information is stored and copied in living organisms and is widely considered one of the most important scientific discoveries of the 20th century. Crick, Wilkins, and Watson each received one third of the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their contributions to the discovery.[18]

Nucleic acid hybridization

Hybridization is the process of complementary base pairs binding to form a double helix. Melting is the process by which the interactions between the strands of the double helix are broken, separating the two nucleic acid strands. These bonds are weak, easily separated by gentle heating, enzymes, or mechanical force. Melting occurs preferentially at certain points in the nucleic acid.[19] T and A rich regions are more easily melted than C and G rich regions. Some base steps (pairs) are also susceptible to DNA melting, such as T A and T G.[20] These mechanical features are reflected by the use of sequences such as TATA at the start of many genes to assist RNA polymerase in melting the DNA for transcription.

Strand separation by gentle heating, as used in polymerase chain reaction (PCR), is simple, providing the molecules have fewer than about 10,000 base pairs (10 kilobase pairs, or 10 kbp). The intertwining of the DNA strands makes long segments difficult to separate. The cell avoids this problem by allowing its DNA-melting enzymes (helicases) to work concurrently with topoisomerases, which can chemically cleave the phosphate backbone of one of the strands so that it can swivel around the other. Helicases unwind the strands to facilitate the advance of sequence-reading enzymes such as DNA polymerase.

Base pair geometry

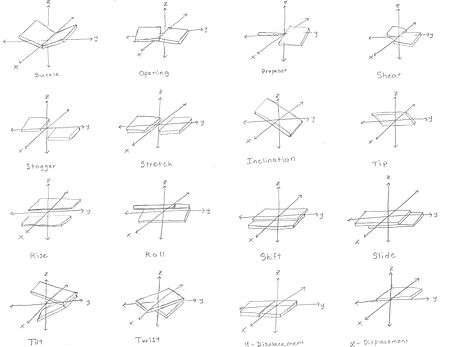

The geometry of a base, or base pair step can be characterized by 6 coordinates: shift, slide, rise, tilt, roll, and twist. These values precisely define the location and orientation in space of every base or base pair in a nucleic acid molecule relative to its predecessor along the axis of the helix. Together, they characterize the helical structure of the molecule. In regions of DNA or RNA where the normal structure is disrupted, the change in these values can be used to describe such disruption.

For each base pair, considered relative to its predecessor, there are the following base pair geometries to consider:[21][22][23]

- Shear

- Stretch

- Stagger

- Buckle

- Propeller: rotation of one base with respect to the other in the same base pair.

- Opening

- Shift: displacement along an axis in the base-pair plane perpendicular to the first, directed from the minor to the major groove.

- Slide: displacement along an axis in the plane of the base pair directed from one strand to the other.

- Rise: displacement along the helix axis.

- Tilt: rotation around the shift axis.

- Roll: rotation around the slide axis.

- Twist: rotation around the rise axis.

- x-displacement

- y-displacement

- inclination

- tip

- pitch: the height per complete turn of the helix.

Rise and twist determine the handedness and pitch of the helix. The other coordinates, by contrast, can be zero. Slide and shift are typically small in B-DNA, but are substantial in A- and Z-DNA. Roll and tilt make successive base pairs less parallel, and are typically small.

Note that "tilt" has often been used differently in the scientific literature, referring to the deviation of the first, inter-strand base-pair axis from perpendicularity to the helix axis. This corresponds to slide between a succession of base pairs, and in helix-based coordinates is properly termed "inclination".

Helix geometries

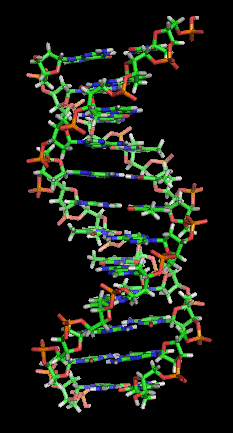

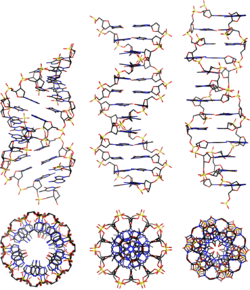

At least three DNA conformations are believed to be found in nature, A-DNA, B-DNA, and Z-DNA. The B form described by James Watson and Francis Crick is believed to predominate in cells.[24] It is 23.7 Å wide and extends 34 Å per 10 bp of sequence. The double helix makes one complete turn about its axis every 10.4–10.5 base pairs in solution. This frequency of twist (termed the helical pitch) depends largely on stacking forces that each base exerts on its neighbours in the chain. The absolute configuration of the bases determines the direction of the helical curve for a given conformation.

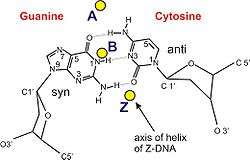

A-DNA and Z-DNA differ significantly in their geometry and dimensions to B-DNA, although still form helical structures. It was long thought that the A form only occurs in dehydrated samples of DNA in the laboratory, such as those used in crystallographic experiments, and in hybrid pairings of DNA and RNA strands, but DNA dehydration does occur in vivo, and A-DNA is now known to have biological functions. Segments of DNA that cells have methylated for regulatory purposes may adopt the Z geometry, in which the strands turn about the helical axis the opposite way to A-DNA and B-DNA. There is also evidence of protein-DNA complexes forming Z-DNA structures.

Other conformations are possible; A-DNA, B-DNA, C-DNA, E-DNA,[25] L-DNA (the enantiomeric form of D-DNA),[26] P-DNA,[27] S-DNA, Z-DNA, etc. have been described so far.[28] In fact, only the letters F, Q, U, V, and Y are now available to describe any new DNA structure that may appear in the future.[29][30] However, most of these forms have been created synthetically and have not been observed in naturally occurring biological systems. There are also triple-stranded DNA forms and quadruplex forms such as the G-quadruplex and the i-motif.

| Geometry attribute | A-DNA | B-DNA | Z-DNA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Helix sense | right-handed | right-handed | left-handed |

| Repeating unit | 1 bp | 1 bp | 2 bp |

| Rotation/bp | 32.7° | 34.3° | 60°/2 |

| bp/turn | 11 | 10.5 | 12 |

| Inclination of bp to axis | +19° | −1.2° | −9° |

| Rise/bp along axis | 2.3 Å (0.23 nm) | 3.32 Å (0.332 nm) | 3.8 Å (0.38 nm) |

| Pitch/turn of helix | 28.2 Å (2.82 nm) | 33.2 Å (3.32 nm) | 45.6 Å (4.56 nm) |

| Mean propeller twist | +18° | +16° | 0° |

| Glycosyl angle | anti | anti | C: anti, G: syn |

| Sugar pucker | C3'-endo | C2'-endo | C: C2'-endo, G: C2'-exo |

| Diameter | 23 Å (2.3 nm) | 20 Å (2.0 nm) | 18 Å (1.8 nm) |

Grooves

Twin helical strands form the DNA backbone. Another double helix may be found by tracing the spaces, or grooves, between the strands. These voids are adjacent to the base pairs and may provide a binding site. As the strands are not directly opposite each other, the grooves are unequally sized. One groove, the major groove, is 22 Å wide and the other, the minor groove, is 12 Å wide.[34] The narrowness of the minor groove means that the edges of the bases are more accessible in the major groove. As a result, proteins like transcription factors that can bind to specific sequences in double-stranded DNA usually make contacts to the sides of the bases exposed in the major groove.[4] This situation varies in unusual conformations of DNA within the cell (see below), but the major and minor grooves are always named to reflect the differences in size that would be seen if the DNA is twisted back into the ordinary B form.

Non-double helical forms

Alternative non-helical models were briefly considered in the late 1970s as a potential solution to problems in DNA replication in plasmids and chromatin. However, the models were set aside in favor of the double-helical model due to subsequent experimental advances such as X-ray crystallography of DNA duplexes and later the nucleosome core particle, and the discovery of topoisomerases. Also, the non-double-helical models are not currently accepted by the mainstream scientific community.[35][36]

Single-stranded nucleic acids (ssDNA) do not adopt a helical formation, and are described by models such as the random coil or worm-like chain.

Bending

DNA is a relatively rigid polymer, typically modelled as a worm-like chain. It has three significant degrees of freedom; bending, twisting, and compression, each of which cause certain limits on what is possible with DNA within a cell. Twisting-torsional stiffness is important for the circularisation of DNA and the orientation of DNA bound proteins relative to each other and bending-axial stiffness is important for DNA wrapping and circularisation and protein interactions. Compression-extension is relatively unimportant in the absence of high tension.

Persistence length, axial stiffness

| Sequence | Persistence length / base pairs |

|---|---|

| Random | 154±10 |

| (CA)repeat | 133±10 |

| (CAG)repeat | 124±10 |

| (TATA)repeat | 137±10 |

DNA in solution does not take a rigid structure but is continually changing conformation due to thermal vibration and collisions with water molecules, which makes classical measures of rigidity impossible to apply. Hence, the bending stiffness of DNA is measured by the persistence length, defined as:

The length of DNA over which the time-averaged orientation of the polymer becomes uncorrelated by a factor of e.

This value may be directly measured using an atomic force microscope to directly image DNA molecules of various lengths. In an aqueous solution, the average persistence length is 46–50 nm or 140–150 base pairs (the diameter of DNA is 2 nm), although can vary significantly. This makes DNA a moderately stiff molecule.

The persistence length of a section of DNA is somewhat dependent on its sequence, and this can cause significant variation. The variation is largely due to base stacking energies and the residues which extend into the minor and major grooves.

Models for DNA bending

| Step | Stacking ΔG /kcal mol−1 |

|---|---|

| T A | -0.19 |

| T G or C A | -0.55 |

| C G | -0.91 |

| A G or C T | -1.06 |

| A A or T T | -1.11 |

| A T | -1.34 |

| G A or T C | -1.43 |

| C C or G G | -1.44 |

| A C or G T | -1.81 |

| G C | -2.17 |

The entropic flexibility of DNA is remarkably consistent with standard polymer physics models, such as the Kratky-Porod worm-like chain model. Consistent with the worm-like chain model is the observation that bending DNA is also described by Hooke's law at very small (sub-piconewton) forces. However, for DNA segments less than the persistence length, the bending force is approximately constant and behaviour deviates from the worm-like chain predictions.

This effect results in unusual ease in circularising small DNA molecules and a higher probability of finding highly bent sections of DNA.

Bending preference

DNA molecules often have a preferred direction to bend, i.e., anisotropic bending. This is, again, due to the properties of the bases which make up the DNA sequence - a random sequence will have no preferred bend direction, i.e., isotropic bending.

Preferred DNA bend direction is determined by the stability of stacking each base on top of the next. If unstable base stacking steps are always found on one side of the DNA helix then the DNA will preferentially bend away from that direction. As bend angle increases then steric hindrances and ability to roll the residues relative to each other also play a role, especially in the minor groove. A and T residues will be preferentially be found in the minor grooves on the inside of bends. This effect is particularly seen in DNA-protein binding where tight DNA bending is induced, such as in nucleosome particles. See base step distortions above.

DNA molecules with exceptional bending preference can become intrinsically bent. This was first observed in trypanosomatid kinetoplast DNA. Typical sequences which cause this contain stretches of 4-6 T and A residues separated by G and C rich sections which keep the A and T residues in phase with the minor groove on one side of the molecule. For example:

| ¦ | ¦ | ¦ | ¦ | ¦ | ¦ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| G | A | T | T | C | C | C | A | A | A | A | A | T | G | T | C | A | A | A | A | A | A | T | A | G | G | C | A | A | A | A | A | A | T | G | C | C | A | A | A | A | A | A | T | C | C | C | A | A | A | C |

The intrinsically bent structure is induced by the 'propeller twist' of base pairs relative to each other allowing unusual bifurcated Hydrogen-bonds between base steps. At higher temperatures this structure is denatured, and so the intrinsic bend is lost.

All DNA which bends anisotropically has, on average, a longer persistence length and greater axial stiffness. This increased rigidity is required to prevent random bending which would make the molecule act isotropically.

Circularization

DNA circularization depends on both the axial (bending) stiffness and torsional (rotational) stiffness of the molecule. For a DNA molecule to successfully circularize it must be long enough to easily bend into the full circle and must have the correct number of bases so the ends are in the correct rotation to allow bonding to occur. The optimum length for circularization of DNA is around 400 base pairs (136 nm), with an integral number of turns of the DNA helix, i.e., multiples of 10.4 base pairs. Having a non integral number of turns presents a significant energy barrier for circularization, for example a 10.4 x 30 = 312 base pair molecule will circularize hundreds of times faster than 10.4 x 30.5 ≈ 317 base pair molecule.[38]

Stretching

Elastic stretching regime

Longer stretches of DNA are entropically elastic under tension. When DNA is in solution, it undergoes continuous structural variations due to the energy available in the thermal bath of the solvent. This is due to the thermal vibration of the molecule combined with continual collisions with water molecules. For entropic reasons, more compact relaxed states are thermally accessible than stretched out states, and so DNA molecules are almost universally found in a tangled relaxed layouts. For this reason, one molecule of DNA will stretch under a force, straightening it out. Using optical tweezers, the entropic stretching behavior of DNA has been studied and analyzed from a polymer physics perspective, and it has been found that DNA behaves largely like the Kratky-Porod worm-like chain model under physiologically accessible energy scales.

Phase transitions under stretching

Under sufficient tension and positive torque, DNA is thought to undergo a phase transition with the bases splaying outwards and the phosphates moving to the middle. This proposed structure for overstretched DNA has been called P-form DNA, in honor of Linus Pauling who originally presented it as a possible structure of DNA.[27]

Evidence from mechanical stretching of DNA in the absence of imposed torque points to a transition or transitions leading to further structures which are generally referred to as S-form DNA. These structures have not yet been definitively characterised due to the difficulty of carrying out atomic-resolution imaging in solution while under applied force although many computer simulation studies have been made (for example,[39][40]).

Proposed S-DNA structures include those which preserve base-pair stacking and hydrogen bonding (GC-rich), while releasing extension by tilting, as well as structures in which partial melting of the base-stack takes place, while base-base association is nonetheless overall preserved (AT-rich).

Periodic fracture of the base-pair stack with a break occurring once per three bp (therefore one out of every three bp-bp steps) has been proposed as a regular structure which preserves planarity of the base-stacking and releases the appropriate amount of extension,[41] with the term "Σ-DNA" introduced as a mnemonic, with the three right-facing points of the Sigma character serving as a reminder of the three grouped base pairs. The Σ form has been shown to have a sequence preference for GNC motifs which are believed under the GNC hypothesis to be of evolutionary importance.[42]

Supercoiling and topology

The B form of the DNA helix twists 360° per 10.4-10.5 bp in the absence of torsional strain. But many molecular biological processes can induce torsional strain. A DNA segment with excess or insufficient helical twisting is referred to, respectively, as positively or negatively supercoiled. DNA in vivo is typically negatively supercoiled, which facilitates the unwinding (melting) of the double-helix required for RNA transcription.

Within the cell most DNA is topologically restricted. DNA is typically found in closed loops (such as plasmids in prokaryotes) which are topologically closed, or as very long molecules whose diffusion coefficients produce effectively topologically closed domains. Linear sections of DNA are also commonly bound to proteins or physical structures (such as membranes) to form closed topological loops.

Francis Crick was one of the first to propose the importance of linking numbers when considering DNA supercoils. In a paper published in 1976, Crick outlined the problem as follows:

In considering supercoils formed by closed double-stranded molecules of DNA certain mathematical concepts, such as the linking number and the twist, are needed. The meaning of these for a closed ribbon is explained and also that of the writhing number of a closed curve. Some simple examples are given, some of which may be relevant to the structure of chromatin.[43]

Analysis of DNA topology uses three values:

- L = linking number - the number of times one DNA strand wraps around the other. It is an integer for a closed loop and constant for a closed topological domain.

- T = twist - total number of turns in the double stranded DNA helix. This will normally tend to approach the number of turns that a topologically open double stranded DNA helix makes free in solution: number of bases/10.5, assuming there are no intercalating agents (e.g., ethidium bromide) or other elements modifying the stiffness of the DNA.

- W = writhe - number of turns of the double stranded DNA helix around the superhelical axis

- L = T + W and ΔL = ΔT + ΔW

Any change of T in a closed topological domain must be balanced by a change in W, and vice versa. This results in higher order structure of DNA. A circular DNA molecule with a writhe of 0 will be circular. If the twist of this molecule is subsequently increased or decreased by supercoiling then the writhe will be appropriately altered, making the molecule undergo plectonemic or toroidal superhelical coiling.

When the ends of a piece of double stranded helical DNA are joined so that it forms a circle the strands are topologically knotted. This means the single strands cannot be separated any process that does not involve breaking a strand (such as heating). The task of un-knotting topologically linked strands of DNA falls to enzymes termed topoisomerases. These enzymes are dedicated to un-knotting circular DNA by cleaving one or both strands so that another double or single stranded segment can pass through. This un-knotting is required for the replication of circular DNA and various types of recombination in linear DNA which have similar topological constraints.

The linking number paradox

For many years, the origin of residual supercoiling in eukaryotic genomes remained unclear. This topological puzzle was referred to by some as the "linking number paradox".[44] However, when experimentally determined structures of the nucleosome displayed an over-twisted left-handed wrap of DNA around the histone octamer,[45][46] this paradox was considered to be solved by the scientific community.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to DNA helix-structures. |

- Triple-stranded DNA

- G-quadruplex

- DNA nanotechnology

- Molecular models of DNA

- Molecular structure of Nucleic Acids (publication)

- Comparison of nucleic acid simulation software

References

- Kabai, Sándor (2007). "Double Helix". The Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Alberts; et al. (1994). The Molecular Biology of the Cell. New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-4105-5.

- Wang JC (1979). "Helical repeat of DNA in solution". PNAS. 76 (1): 200–203. Bibcode:1979PNAS...76..200W. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.1.200. PMC 382905. PMID 284332.

- Pabo C, Sauer R (1984). "Protein-DNA recognition". Annu Rev Biochem. 53: 293–321. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.001453. PMID 6236744.

- James Watson and Francis Crick (1953). "A structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid" (PDF). Nature. 171 (4356): 737–738. Bibcode:1953Natur.171..737W. doi:10.1038/171737a0. PMID 13054692.

- Crick F, Watson JD (1954). "The Complementary Structure of Deoxyribonucleic Acid" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 223, Series A: 80–96.

- "Secret of Photo 51". Nova. PBS.

- http://www.nature.com/nature/dna50/franklingosling.pdf

- "The Structure of the DNA Molecule". Archived from the original on 2012-06-21. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- Wilkins MH, Stokes AR, Wilson HR (1953). "Molecular Structure of Deoxypentose Nucleic Acids" (PDF). Nature. 171 (4356): 738–740. Bibcode:1953Natur.171..738W. doi:10.1038/171738a0. PMID 13054693.

- Elson D, Chargaff E (1952). "On the deoxyribonucleic acid content of sea urchin gametes". Experientia. 8 (4): 143–145. doi:10.1007/BF02170221. PMID 14945441.

- Chargaff E, Lipshitz R, Green C (1952). "Composition of the deoxypentose nucleic acids of four genera of sea-urchin". J Biol Chem. 195 (1): 155–160. PMID 14938364.

- Chargaff E, Lipshitz R, Green C, Hodes ME (1951). "The composition of the deoxyribonucleic acid of salmon sperm". J Biol Chem. 192 (1): 223–230. PMID 14917668.

- Chargaff E (1951). "Some recent studies on the composition and structure of nucleic acids". J Cell Physiol Suppl. 38 (Suppl).

- Magasanik B, Vischer E, Doniger R, Elson D, Chargaff E (1950). "The separation and estimation of ribonucleotides in minute quantities". J Biol Chem. 186 (1): 37–50. PMID 14778802.

- Chargaff E (1950). "Chemical specificity of nucleic acids and mechanism of their enzymatic degradation". Experientia. 6 (6): 201–209. doi:10.1007/BF02173653. PMID 15421335.

- Pauling L, Corey RB (Feb 1953). "A proposed structure for the nucleic acids". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 39 (2): 84–97. Bibcode:1953PNAS...39...84P. doi:10.1073/pnas.39.2.84. PMC 1063734. PMID 16578429.

- "Nobel Prize - List of All Nobel Laureates".

- Breslauer KJ, Frank R, Blöcker H, Marky LA (1986). "Predicting DNA duplex stability from the base sequence". PNAS. 83 (11): 3746–3750. Bibcode:1986PNAS...83.3746B. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.11.3746. PMC 323600. PMID 3459152.

- Owczarzy, Richard (2008-08-28). "DNA melting temperature - How to calculate it?". High-throughput DNA biophysics. owczarzy.net. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- Dickerson RE (1989). "Definitions and nomenclature of nucleic acid structure components". Nucleic Acids Res. 17 (5): 1797–1803. doi:10.1093/nar/17.5.1797. PMC 317523. PMID 2928107.

- Lu XJ, Olson WK (1999). "Resolving the discrepancies among nucleic acid conformational analyses". J Mol Biol. 285 (4): 1563–1575. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1998.2390. PMID 9917397.

- Olson WK, Bansal M, Burley SK, Dickerson RE, Gerstein M, Harvey SC, Heinemann U, Lu XJ, Neidle S, Shakked Z, Sklenar H, Suzuki M, Tung CS, Westhof E, Wolberger C, Berman HM (2001). "A standard reference frame for the description of nucleic acid base-pair geometry". J Mol Biol. 313 (1): 229–237. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2001.4987. PMID 11601858.

- Richmond; Davey, CA; et al. (2003). "The structure of DNA in the nucleosome core". Nature. 423 (6936): 145–150. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..145R. doi:10.1038/nature01595. PMID 12736678.

- Vargason JM, Eichman BF, Ho PS (2000). "The extended and eccentric E-DNA structure induced by cytosine methylation or bromination". Nature Structural Biology. 7 (9): 758–761. doi:10.1038/78985. PMID 10966645.

- Hayashi G, Hagihara M, Nakatani K (2005). "Application of L-DNA as a molecular tag". Nucleic Acids Symp Ser (Oxf). 49 (1): 261–262. doi:10.1093/nass/49.1.261. PMID 17150733.

- Allemand JF, Bensimon D, Lavery R, Croquette V (1998). "Stretched and overwound DNA forms a Pauling-like structure with exposed bases". PNAS. 95 (24): 14152–14157. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9514152A. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.24.14152. PMC 24342. PMID 9826669.

- List of 55 fiber structures Archived 2007-05-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Bansal M (2003). "DNA structure: Revisiting the Watson-Crick double helix". Current Science. 85 (11): 1556–1563.

- Ghosh A, Bansal M (2003). "A glossary of DNA structures from A to Z". Acta Crystallogr D. 59 (4): 620–626. doi:10.1107/S0907444903003251. PMID 12657780.

- Rich A, Norheim A, Wang AH (1984). "The chemistry and biology of left-handed Z-DNA". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 53: 791–846. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.004043. PMID 6383204.

- Sinden, Richard R (1994-01-15). DNA structure and function (1st ed.). Academic Press. p. 398. ISBN 0-12-645750-6.

- Ho PS (1994-09-27). "The non-B-DNA structure of d(CA/TG)n does not differ from that of Z-DNA". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 91 (20): 9549–9553. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.9549H. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.20.9549. PMC 44850. PMID 7937803.

- Wing R, Drew H, Takano T, Broka C, Tanaka S, Itakura K, Dickerson R (1980). "Crystal structure analysis of a complete turn of B-DNA". Nature. 287 (5784): 755–8. Bibcode:1980Natur.287..755W. doi:10.1038/287755a0. PMID 7432492.

- Stokes, T. D. (1982). "The double helix and the warped zipper—an exemplary tale". Social Studies of Science. 12 (2): 207–240. doi:10.1177/030631282012002002. PMID 11620855.

- Gautham, N. (25 May 2004). "Response to 'Variety in DNA secondary structure'" (PDF). Current Science. 86 (10): 1352–1353. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

However, the discovery of topoisomerases took "the sting" out of the topological objection to the plectonaemic double helix. The more recent solution of the single crystal X-ray structure of the nucleosome core particle showed nearly 150 base pairs of the DNA (i.e., about 15 complete turns), with a structure that is in all essential respects the same as the Watson–Crick model. This dealt a death blow to the idea that other forms of DNA, particularly double helical DNA, exist as anything other than local or transient structures.

- Protozanova E, Yakovchuk P, Frank-Kamenetskii MD (2004). "Stacked–Unstacked Equilibrium at the Nick Site of DNA". J Mol Biol. 342 (3): 775–785. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.075. PMID 15342236.

- Travers, Andrew (2005). "DNA Dynamics: Bubble 'n' Flip for DNA Cyclisation?". Current Biology. 15 (10): R377–R379. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.007. PMID 15916938.

- Konrad MW, Bolonick JW (1996). "Molecular dynamics simulation of DNA stretching is consistent with the tension observed for extension and strand separation and predicts a novel ladder structure". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 118 (45): 10989–10994. doi:10.1021/ja961751x.

- Roe DR, Chaka AM (2009). "Structural basis of pathway-dependent force profiles in stretched DNA". Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 113 (46): 15364–15371. doi:10.1021/jp906749j. PMID 19845321.

- Bosaeus N, Reymer A, Beke-Somfai T, Brown T, Takahashi M, Wittung-Stafshede P, Rocha S, Nordén B (2017). "A stretched conformation of DNA with a biological role?". Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 50: e11. doi:10.1017/S0033583517000099. PMID 29233223.

- Taghavi A, van Der Schoot P, Berryman JT (2017). "DNA partitions into triplets under tension in the presence of organic cations, with sequence evolutionary age predicting the stability of the triplet phase". Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 50. doi:10.1017/S0033583517000130. PMID 29233227.

- Crick FH (1976). "Linking numbers and nucleosomes". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 73 (8): 2639–43. Bibcode:1976PNAS...73.2639C. doi:10.1073/pnas.73.8.2639. PMC 430703. PMID 1066673.

- Prunell A (1998). "A topological approach to nucleosome structure and dynamics: the linking number paradox and other issues". Biophys J. 74 (5): 2531–2544. Bibcode:1998BpJ....74.2531P. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77961-5. PMC 1299595. PMID 9591679.

- Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ (1997). "Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution". Nature. 389 (6648): 251–260. Bibcode:1997Natur.389..251L. doi:10.1038/38444. PMID 9305837.

- Davey CA, Sargent DF, Luger K, Maeder AW, Richmond TJ (2002). "Solvent mediated interactions in the structure of the nucleosome core particle at 1.9 Å resolution". Journal of Molecular Biology. 319 (5): 1097–1113. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00386-8. PMID 12079350.