Mudra

A mudra (/muˈdrɑː/ (![]()

As well as being spiritual gestures employed in the iconography and spiritual practice of Indian religions, mudras have meaning in many forms of Indian dance, and yoga. The range of mudras used in each field (and religion) differs, but with some overlap. In addition, many of the Buddhist mudras are used outside South Asia, and have developed different local forms elsewhere.

In hatha yoga, mudras are used in conjunction with pranayama (yogic breathing exercises), generally while in a seated posture, to stimulate different parts of the body involved with breathing and to affect the flow of prana, bindu (male psycho-sexual energy), boddhicitta, amrita or consciousness in the body. Unlike older tantric mudras, hatha yogic mudras are generally internal actions, involving the pelvic floor, diaphragm, throat, eyes, tongue, anus, genitals, abdomen, and other parts of the body. Examples of this diversity of mudras are Mula Bandha, Mahamudra, Viparita Karani, Khecarī mudrā, and Vajroli mudra. These expanded in number from 3 in the Amritasiddhi, to 25 in the Gheranda Samhita, with a classical set of ten arising in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika.

Nomenclature

The Chinese translation is yin (Chinese: 印; pinyin: yìn) or yinxiang (Chinese: 印相; pinyin: yìnxiàng). Both these Chinese words also appear as loanwords in Japanese (as in and inzō or insō, respectively) and Korean (as in and insang, respectively). Two other Chinese-based compounds, 印契 (read as ingei or inkei in Japanese and as ingye in Korean) and 密印 (read as mitsuin or mitchin in Japanese and as mirin in Korean), are also used. In Japanese, the former compound may also be used with the order of the characters reversed (i.e. 契印 keiin).

Iconography

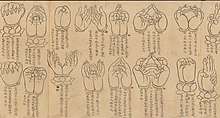

Mudra is used in the iconography of Hindu and Buddhist art of the Indian subcontinent and described in the scriptures, such as Nātyaśāstra, which lists 24 asaṁyuta ("separated", meaning "one-hand") and 13 saṁyuta ("joined", meaning "two-hand") mudras. Mudra positions are usually formed by both the hand and the fingers. Along with āsanas ("seated postures"), they are employed statically in the meditation and dynamically in the Nāṭya practice of Hinduism.

Hindu and Buddhist iconography share some mudras. In some regions, for example in Laos and Thailand, these are distinct but share related iconographic conventions.

According to Jamgön Kongtrül in his commentary on the Hevajra Tantra, the ornaments of wrathful deities and witches made of human bones (Skt: aṣṭhimudrā; Wylie: rus pa'i rgyanl phyag rgya ) are also known as mudra "seals".[3]

Buddhism

A Buddha image can have one of several common mudras, combined with different asanas. The main mudras used represent specific moments in the life of Gautama Buddha, and are shorthand depictions of these.

Abhaya Mudrā

.jpg)

The Abhayamudra "gesture of fearlessness"[4] represents protection, peace, benevolence and the dispelling of fear. In Theravada Buddhism it is usually made while standing with the right arm bent and raised to shoulder height, the palm facing forward, the fingers closed, pointing upright and the left hand resting by the side. In Thailand and Laos, this mudra is associated with the walking Buddha, often shown having both hands making a double abhaya mudra that is uniform.

This mudra was probably used before the onset of Buddhism as a symbol of good intentions proposing friendship when approaching strangers. In Gandharan art, it is seen when showing the action of preaching. It was also used in China during the Wei and Sui eras of the 4th and 7th centuries.

This gesture was used by the Buddha when attacked by an elephant, subduing it as shown in several frescoes and scripts.[5]

In Mahayana Buddhism, the deities are often portrayed as pairing the Abhaya Mudrā with another Mudrā using the other hand.

Bhūmisparśa Mudrā

The bhūmisparśa or "earth witness" mudra of Gautama Buddha is one of the most common iconic images of Buddhism. Other names include "Buddha calling the earth to witness", and "earth-touching". It depicts the story from Buddhist legend of the moment when Buddha achieved complete enlightenment, with Buddha sitting in meditation with his left hand, palm upright, in his lap, and his right hand touching the earth. In the story the Buddha was challenged by the demon Mara, who asked him for a witness to attest his right to achieve it. In reply he touched the ground, asking Pṛthivi, the devi of the earth, that she witness his enlightenment, which she did.[6][7]

In South-East and East Asia this mudra (also called the Maravijaya attitude) may show Buddha's fingers not reaching as far as the ground, as is usual in Indian depictions.

Bodhyangi Mudrā

The Bodhyangi mudrā, the "mudrā of the six elements," or the "fist of wisdom,"[8] is a gesture entailing the left-hand index finger being grasped with the right hand. It is commonly seen on statues of the Vairocana Buddha.

Dharmachakra Pravartana Mudrā

.jpg)

The Buddha preached his first sermon after his Enlightenment in Deer Park in Sarnath. The dharmachakra Pravartana or "turning of the wheel"[9] mudrā represents that moment. In general, only Gautama Buddha is shown making this mudrā except Maitreya as the dispenser of the Law. Dharmachakra mudrā is two hands close together in front of the chest in vitarka with the right palm forward and the left palm upward, sometimes facing the chest. There are several variants such as in the Ajanta Caves frescoes, where the two hands are separated and the fingers do not touch. In the Indo-Greek style of Gandhara, the clenched fist of the right hand seemingly overlies the fingers joined to the thumb on the left hand. In pictorials of Hōryū-ji in Japan the right hand is superimposed on the left. Certain figures of Amitābha, Japan are seen using this mudra before the 9th century.

Dhyāna Mudrā

The dhyāna mudrā ("meditation mudra") is the gesture of meditation, of the concentration of the Good Law and the sangha. The two hands are placed on the lap, left hand on right with fingers fully stretched (four fingers resting on each other and the thumbs facing upwards towards one another diagonally), palms facing upwards; in this manner, the hands and fingers form the shape of a triangle, which is symbolic of the spiritual fire or the Three Jewels. This mudra is used in representations of Gautama Buddha and Amitābha. Sometimes the dhyāna mudrā is used in certain representations of Bhaiṣajyaguru as the "Medicine Buddha", with a medicine bowl placed on the hands. It originated in India most likely in Gandhāra and in China during the Northern Wei.

It is heavily used in Southeast Asia in Theravada Buddhism; however, the thumbs are placed against the palms. Dhyāna mudrā is also known as "samādhi mudrā" or "yoga mudrā", Chinese: 禅定印; pinyin: [Chán]dìng yìn; Japanese pronunciation: jōin, jōkai jōin.

The mida no jōin (弥陀定印) is the Japanese name of a variation of the dhyāna mudra, where the index fingers are brought together with the thumbs. This was predominately used in Japan in an effort to distinguish Amitābha (hence "mida" from Amida) from the Vairocana Buddha,[10] and was rarely used elsewhere.

Varada Mudrā

The Varadamudrā "generosity gesture" signifies offering, welcome, charity, giving, compassion and sincerity. It is nearly always shown made with the left hand by a revered figure devoted to human salvation from greed, anger and delusion. It can be made with the arm crooked and the palm offered slightly turned up or in the case of the arm facing down the palm presented with the fingers upright or slightly bent. The Varada mudrā is rarely seen without another mudra used by the right hand, typically abhaya mudrā. It is often confused with vitarka mudrā, which it closely resembles. In China and Japan during the Northern Wei and Asuka periods, respectively, the fingers are stiff and then gradually begin to loosen as it developed over time, eventually leading to the Tang dynasty standard where the fingers are naturally curved.

In India, varada mudra is used by both seated and standing figures, of Buddha and boddhisatvas and other figures, and in Hindu art is especially associated with Vishnu. It was used in images of Avalokiteśvara from Gupta art (4th and 5th centuries) onwards. Varada mudrā is extensively used in the statues of Southeast Asia.

Vajra Mudrā

The Vajra mudrā "thunder gesture" is the gesture of knowledge.[11] An example of the application of the Vajra mudrā is the seventh technique (out of nine) of the Nine Syllable Seals.

Vitarka Mudrā

The Vitarka mudrā "mudra of discussion" is the gesture of discussion and transmission of Buddhist teaching. It is done by joining the tips of the thumb and the index together, and keeping the other fingers straight very much like the abhaya and varada mudrās but with the thumbs touching the index fingers. This mudra has a great number of variants in Mahayana Buddhism. In Tibetan Buddhism, it is the mystic gesture of Tārās and bodhisattvas with some differences by the deities in Yab-Yum. Vitarka mudrā is also known as Vyākhyāna mudrā ("mudra of explanation").

Gyana Mudrā

The gyāna mudrā ("mudra of wisdom") is done by touching the tips of the thumb and the index together, forming a circle, and the hand is held with the palm inward toward the heart.[12]

Karana Mudrā

The karana mudrā is the mudra which expels demons and removes obstacles such as sickness or negative thoughts. It is made by raising the index and the little finger, and folding the other fingers. It is nearly the same as the Western "sign of the horns", the difference is that in the Karana mudra the thumb does not hold down the middle and ring finger. This mudra is also known as tarjanī mudrā; Japanese: Funnu-in, Fudō-in.

Indian classical dance

In Indian classical dance, the term "Hasta Mudra" is used. The Natya Shastra describes 24 mudras, while the Abhinaya Darpana of Nandikeshvara gives 28.[13] In all their forms of Indian classical dance, the mudras are similar, though the names and uses vary. There are 28 (or 32) root mudras in Bharatanatyam, 24 in Kathakali and 20 in Odissi. These root mudras are combined in different ways, like one hand, two hands, arm movements, body and facial expressions. In Kathakali, which has the greatest number of combinations, the vocabulary adds up to c. 900. Sanyukta mudras use both hands and asanyukta mudras use one hand.[14]

Yoga

The classical sources for the mudras in yoga are the Gheranda Samhita and the Hatha Yoga Pradipika.[15] The Hatha Yoga Pradipika states the importance of mudras in yoga practice: "Therefore the [Kundalini] goddess sleeping at the entrance of Brahma's door [at the base of the spine] should be constantly aroused with all effort, by performing mudra thoroughly." In the 20th and 21st centuries, the yoga teacher Satyananda Saraswati, founder of the Bihar School of Yoga, continued to emphasize the importance of mudras in his instructional text Asana, Pranayama, Mudrā, Bandha.[15]

The yoga mudras are diverse in the parts of the body involved and in the procedures required, as in Mula Bandha,[16] Mahamudra,[17] Viparita Karani,[18] Khecarī mudrā,[19] and Vajroli mudra.[20]

Mula Bandha

Mula Bandha, the Root Lock, consists of pressing one heel into the anus, generally in a cross-legged seated asana, and contracting the perineum, forcing the prana to enter the central sushumna channel.[16]

Mahamudra

Mahamudra, the Great Seal, similarly has one heel pressed into the perineum; the chin is pressed down to the chest in Jalandhara Bandha, the Throat Lock, and the breath is held with the body's upper and lower openings both sealed, again to force the prana into the sushumna channel.[17]

Viparita Karani

Viparita Karani, the Inverter, is a posture with the head down and the feet up, using gravity to retain the prana. Gradually the time spent in the posture is increased until it can be held for "three hours". The practice is claimed by the Dattatreyayogashastra to destroy all diseases and to banish grey hair and wrinkles.[18]

Khechari mudra

Khecarī mudrā, the Khechari Seal, consists of turning back the tongue "into the hollow of the skull",[19] sealing in the bindu fluid so that it stops dripping down from the head and being lost, even when the yogi "embraces a passionate woman".[19] To make the tongue long and flexible enough to be folded back in this way, the Khecharividya exhorts the yogi to make a cut a hair's breadth deep in the frenulum of the tongue once a week. Six months of this treatment destroys the frenulum, leaving the tongue able to fold back; then the yogi is advised to practise stretching the tongue out, holding it with a cloth, to lengthen it, and to learn to touch each ear in turn, and the base of the chin. After six years of practice, which cannot be hurried, the tongue is said to become able to close the top end of the sushumna channel.[22]

Martial arts

Some Asian martial arts forms contain positions (Japanese: in) identical to these mudras.[23] Tendai and Shingon Buddhism derived the supposedly powerful gestures from Mikkyo Buddhism, still to be found in many Ko-ryū ("old") martial arts Ryū (schools) founded before the 17th century. For example the "knife hand" or shuto gesture is subtly concealed in some Koryu kata, and in Buddhist statues, representing the sword of enlightenment.[24]

See also

- List of mudras (yoga)

- List of mudras (dance)

- Iconography of Gautama Buddha in Laos and Thailand

- Mahamudra

- Tea ceremony

- Pranāma

- Yab-Yum

- Yogamudrasana, a variant of lotus pose that is both an asana and a mudra

Notes

- Encyclopædia Britannica. (2010). "mudra (symbolic gestures)". Retrieved October 11, 2010.

- Word mudrā on Monier-William Sanskrit-English on-line dictionary: "N. of partic. positions or intertwinings of the fingers (24 in number, commonly practised in religious worship, and supposed to possess an occult meaning and magical efficacy Daś (Daśakumāra-carita). Sarvad. Kāraṇḍ. RTL. 204; 406)"

- Kongtrul, Jamgön (author); (English translators: Guarisco, Elio; McLeod, Ingrid) (2005). The Treasury of Knowledge (shes bya kun la khyab pa’i mdzod). Book Six, Part Four: Systems of Buddhist Tantra, The Indestructibe Way of Secret Mantra. Bolder, Colorado, USA: Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 1-55939-210-X (alk.paper) p.493

- Buswell, Robert Jr., ed. (2013). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780691157863.

- "Abhaya Mudra Gesture of Dispelling Fear". Retrieved 2019-02-03.

One day the Buddha walked through a village. Devadatta fed alcohol to a particularly furious elephant named Nalagiri and had him attack the Buddha. The raging bull stormed towards the Buddha, who reached out his hand to touch the animal’s trunk. The elephant sensed the metta, the loving kindness of the Buddha, which calmed him down immediately. The animal stopped in front of the Buddha and bowed on his knees in submission.

- Shaw, Miranda Eberle (2006). Buddhist Goddesses of India. Princeton University Press. pp. 17–27. ISBN 978-0-691-12758-3.

- Vessantara, Meeting the Buddhas: A Guide to Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and Tantric Deities, pp. 74-76, 1993, Windhorse Publications, ISBN 0904766535, 9780904766530, google books

- T.W. Rhys Davids Ph.D. LLD.; Victoria Charles (24 November 2014). 1000 Buddhas of Genius. Parkstone International. p. 515. ISBN 978-1-78310-463-5.

- explanation of Buddhist Mudras

- Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. "JAANUS / mida-no-jouin 弥陀定印". Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- written; Beer, illustrated by Robert (2003). The handbook of tibetan buddhist symbols (1st ed.). Chicago (Ill.): Serindia. p. 228. ISBN 978-1932476033.

- For translation of jñānamudrā as "gesture of knowledge" see: Stutley 2003, p. 60.

- Devi, Ragini. Dance dialects of India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1990. ISBN 81-208-0674-3. Pp. 43.

- Barba & Savarese 1991, pp. 136

- Saraswati, Satyananda (1997). Asana Pranayama Mudrā Bandha. Munger, Bihar India: Bihar Yoga Bharti. p. 422. ISBN 81-86336-04-4.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 242.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 237-238, 241.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 242, 245.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 241, 244-245.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 242, 250-252.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. Chapter 6, especially pages 228–229.

- Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 247-249.

- Johnson 2000, p. 48.

- Muromoto, Wayne (2003) Mudra in the Martial Arts Archived 2007-12-15 at the Wayback Machine. . Retrieved December 20, 2007.

References

- Barba, Eugenio; Savarese, Nicola (1991). A dictionary of theatre anthropology: the secret art of the performer. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 0-415-05308-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Draeger, Donn (1980). "Esoteric Buddhism in Japanese Warriorship", in: No. 3. 'Zen and the Japanese Warrior' of the International Hoplological Society Donn F. Draeger Monograph Series. The DFD monographs are transcriptions of lectures presented by Donn Draeger in the late 1970s and early 1980s at the University of Hawaii and at seminars in Malaysia.

- Johnson, Nathan J. (2000). Barefoot Zen: The Shaolin Roots of Kung Fu and Karate. York Beach, USA: Weiser. ISBN 1-57863-142-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mallinson, James; Singleton, Mark (2017). Roots of Yoga. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-241-25304-5. OCLC 928480104.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stutley, Margaret (2003) [1985]. The Illustrated Dictionary of Hindu Iconography (First Indian ed.). New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. ISBN 81-215-1087-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Saunders, Ernest Dale (1985). Mudra: A Study of Symbolic Gestures in Japanese Buddhist Sculpture. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01866-9.

- Hirschi, Gertrud. Mudras: Yoga in Your Hands.

- Taisen Miyata: A study of the ritual mudras in the Shingon tradition: A phenomenological study on the eighteen ways of esoteric recitation in the Koyasan tradition. Publisher s.n.

- Acharya Keshav Dev: Mudras for Healing; Mudra Vigyan: A Way of Life. Acharya Shri Enterprises, 1995. ISBN 9788190095402 .

- Gauri Devi: Esoteric Mudras of Japan. International. Academy of Indian Culture & Aditya Prakashan, 1999. ISBN 9788186471562.

- Lokesh Chandra & Sharada Rani: Mudras in Japan. Vedams Books, 2001. ISBN 9788179360002.

- Emma I. Gonikman: Taoist Healing Gestures. YBK Publishers, Inc., 2003. ISBN 9780970392343.

- Fredrick W. Bunce: Mudras in Buddhist and Hindu Practices: An Iconographic Consideration. DK Printworld, 2005. ISBN 9788124603123.

- A. S. Umar Sharif: Unlocking the Healing Powers in Your Hands: The 18 Mudra System of Qigong. Scholary, Inc, 2006. ISBN 978-0963703637.

- Dhiren Gala: Health at Your Fingertips: Mudra Therapy, a Part of Ayurveda Is Very Effective Yet Costs Nothing. Navneet, 2007. ISBN 9788124603123.

- K. Rangaraja Iyengar: The World of Mudras/Health Related and other Mudras. Sapna Book house, 2007. ISBN 9788128006975.

- Suman K Chiplunkar: Mudras & Health Perspectives: An Indian Approach. Abhijit Prakashana, 2008. ISBN 9788190587440.

- Acharya Keshav Dev: Healing Hands (Science of Yoga Mudras). Acharya Shri Enterprises, 2008. ISBN 9788187949121.

- Cain Carroll and Revital Carroll: Mudras of India: A Comprehensive Guide to the Hand Gestures of Yoga and Indian Dance. Singing Dragon, 2012. ISBN 9781848190849.

- Joseph and Lilian Le Page: Mudras for Healing and Transformation. Integratieve Yoga Therapy, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9744303-4-8.

- Toki, Hôryû; Kawamura, Seiichi, tr. (1899). "Si-do-in-dzou; gestes de l'officiant dans les cérémonies mystiques des sectes Tendaï et Singon", Paris, E. Leroux.

- Adams, Autumn: The Little Book of Mudra Meditations. Rockridge Press, 2020. ISBN 9781646114900.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mudras. |

| Look up mudra in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |