Monaco Grand Prix

The Monaco Grand Prix (French: Grand Prix de Monaco) is a Formula One motor race held annually on the Circuit de Monaco on the last weekend in May. Run since 1929, it is widely considered to be one of the most important and prestigious automobile races in the world,[1][2][3] and is one of the races—along with the Indianapolis 500 and the 24 Hours of Le Mans—that form the Triple Crown of Motorsport.[4] The circuit has been called "an exceptional location of glamour and prestige".[5]

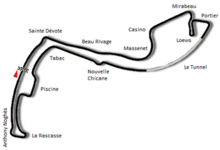

| Circuit de Monaco | |

| |

| Race information | |

|---|---|

| Number of times held | 77 |

| First held | 1929 |

| Most wins (drivers) | |

| Most wins (constructors) | |

| Circuit length | 3.337 km (2.074 mi) |

| Race length | 260.286 km (161.734 mi) |

| Laps | 78 |

| Last race (2019) | |

| Pole position | |

| |

| Podium | |

| Fastest lap | |

| |

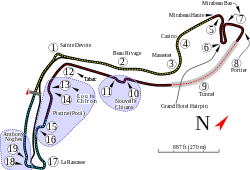

The race is held on a narrow course laid out in the streets of Monaco, with many elevation changes and tight corners as well as a tunnel, making it one of the most demanding tracks in Formula One. In spite of the relatively low average speeds, the Monaco circuit is a dangerous place to race and often involves the intervention of a safety car. It is the only Grand Prix that does not adhere to the FIA's mandated 305-kilometre (190-mile) minimum race distance for F1 races.[6]

The Monaco Grand Prix was part of the pre-Second World War European Championship and was included in the first World Championship of Drivers in 1950. It was designated the European Grand Prix two times, 1955 and 1963, when this title was an honorary designation given each year to one Grand Prix race in Europe. Graham Hill was known as "Mr. Monaco"[7] due to his five Monaco wins in the 1960s. Ayrton Senna won the race more times than any other driver, with six victories, winning five races consecutively between 1989 and 1993.[8]

History

Origins

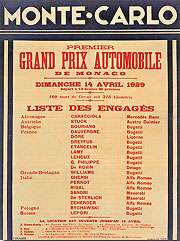

Like many European races, the Monaco Grand Prix predates the current World Championship. The principality's first Grand Prix was organised in 1929 by Antony Noghès, under the auspices of Prince Louis II, through the Automobile Club de Monaco (ACM), of which he was president.[9] The ACM organised the Rallye Automobile Monte Carlo, and in 1928 applied to the Association Internationale des Automobiles Clubs Reconnus (AIACR), the international governing body of motorsport, to be upgraded from a regional French club to full national status. Their application was refused due to the lack of a major motorsport event held wholly within Monaco's boundaries. The rally could not be considered as it mostly used the roads of other European countries.[10]

To attain full national status, Noghès proposed the creation of an automobile Grand Prix in the streets of Monte Carlo. He obtained the official sanction of Prince Louis II, and the support of Monégasque Grand Prix driver Louis Chiron. Chiron thought Monaco's topography well-suited to setting up a race track.[10]

The first race, held on 14 April 1929, was won by William Grover-Williams (using the pseudonym "Williams"), driving a works Bugatti Type 35B.[7][11] It was an invitation-only event, but not all of those invited decided to attend. The leading Maserati and Alfa Romeo drivers decided not to compete, but Bugatti was well represented. Mercedes sent their leading driver, Rudolf Caracciola. Starting fifteenth, Caracciola drove a fighting race, taking his SSK into the lead before wasting 4½ minutes on refuelling and a tyre change to finish second.[7][12] Another driver who competed using a pseudonym was "Georges Philippe", the Baron Philippe de Rothschild. Chiron was unable to compete, having a prior commitment to compete in the Indianapolis 500 on the same day.[10]

Caracciola's SSK was refused permission to race the following year,[12] but Chiron did compete (in the works Bugatti Type 35C), when he was beaten by privateer René Dreyfus and his Bugatti Type 35B, and finished second. Chiron took victory in the 1931 race driving a Bugatti. As of 2019, he remains the only native of Monaco to have won the event.[13]

Pre-war

The race quickly grew in importance after its inception. Because of the high number of races which were being termed 'Grands Prix', the AIACR formally recognised the most important race of each of its affiliated national automobile clubs as International Grands Prix, or Grandes Épreuves, and in 1933 Monaco was ranked as such alongside the French, Belgian, Italian, and Spanish Grands Prix.[14] That year's race was the first Grand Prix in which grid positions were decided, as they are now, by practice time rather than the established method of balloting. The race saw Achille Varzi and Tazio Nuvolari exchange the lead many times before the race being settled in Varzi's favour on the final lap when Nuvolari's car caught fire.[15]

The race became a round of the new European Championship in 1936, when stormy weather and a broken oil line led to a series of crashes, eliminating the Mercedes-Benzes of Chiron, Fagioli, and von Brauchitsch, as well as Bernd Rosemeyer's Typ C for newcomer Auto Union; Rudolf Caracciola, proving the truth of his nickname, Regenmeister (Rainmaster), went on to win.[16] In 1937, von Brauchitsch duelled Caracciola before coming out on top.[17] It was the last prewar Grand Prix at Monaco, for in 1938, the demand for £500 (about US$2450) in appearance money per top entrant led AIACR to cancel the event, while looming war overtook it in 1939, and the Second World War ended organised racing in Europe until 1945.

Post-war Grand Prix

Racing in Europe started again on 9 September 1945 at the Bois de Boulogne Park in the city of Paris, four months and one day after the end of the war in Europe.[18] However, the Monaco Grand Prix was not run between 1945 and 1947 due to financial reasons.[19] In 1946 a new premier racing category, Grand Prix, was defined by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA), the successor of the AIACR, based on the pre-war voiturette class. A Monaco Grand Prix was run to this formula in 1948, won by the future world champion Nino Farina in a Maserati 4CLT.[20][21]

Formula One

Early championship days

The 1949 event was cancelled due to the death of Prince Louis II;[19] it was included in the new Formula One World Drivers' Championship the following year. The race provided future five-time world champion Juan Manuel Fangio with his first win in a World Championship race, as well as third place for the 51-year-old Louis Chiron, his best result in the World Championship era. However, there was no race in 1951. In 1952, the first of the two years in which the World Drivers' Championship was run to less powerful Formula Two regulations, the race was run to sports car rules instead, and it did not form part of the World Championship.[7]

No races were held in 1953 or 1954.[22]

Since 1955, the Monaco Grand Prix has continuously been part of the Formula One World Championship.[23] That year, Maurice Trintignant won in Monte Carlo for the first time and Chiron again scored points and at 56 became the oldest driver to compete in a Formula One Grand Prix. It was not until 1957, when Fangio won again, that the Grand Prix saw a double winner. Between 1954 and 1961 Fangio's former Mercedes colleague, Stirling Moss, went one better, as did Trintignant, who won the race again in 1958 driving a Cooper. The 1961 race saw Moss fend off three works Ferrari 156s in a year-old privateer Rob Walker Racing Team Lotus 18, to take his third Monaco victory.[24]

Graham Hill's era

Britain's Graham Hill won the race five times in the 1960s and became known as "King of Monaco"[25] and "Mr. Monaco". He first won in 1963, and then won the next two years.[7] In the 1965 race he took pole position and led from the start, but went up an escape road on lap 25 to avoid hitting a slow backmarker. Re-joining in fifth place, Hill set several new lap records on the way to winning.[26] The race was also notable for Jim Clark's absence (he was doing the Indianapolis 500), and for Paul Hawkins's Lotus ending up in the harbour.[27] Hill's teammate, Briton Jackie Stewart, won in 1966 and New Zealander Denny Hulme won in 1967, but Hill won the next two years, the 1969 event being his final Formula One championship victory, by which time he was a double Formula One world champion.[28]

Track alterations, safety, and increasing business interests

By the start of the 1970s, efforts by Jackie Stewart saw several Formula One events cancelled because of safety concerns. For the 1969 event, Armco barriers were placed at specific points for the first time in the circuit's history. Before that, the circuit's conditions were (aside from the removal of people's production cars parked on the side of the road) virtually identical to everyday road use. If a driver went off, he had a chance to crash into whatever was next to the track (buildings, trees, lamp posts, glass windows, and even a train station), and in Alberto Ascari's and Paul Hawkins's cases, the harbour water, because the concrete road the course used had no Armco to protect the drivers from going off the track and into the Mediterranean. The circuit gained more Armco in specific points for the next two races, and by 1972, the circuit was almost completely Armco-lined. For the first time in its history, the Monaco circuit was altered in 1972 as the pits were moved next to the waterfront straight between the chicane and Tabac and the chicane was moved further forward right before Tabac becoming the junction point between the pits and the course. The course was changed again for the 1973 race. The Rainier III Nautical Stadium was constructed where the straight that went behind the pits was and the circuit introduced a double chicane that went around the new swimming pool (this chicane complex is known today as "Swimming Pool"). This created space for a whole new pit facility and in 1976 the course was altered yet again; the Sainte Devote corner was made slower and a chicane was placed right before the pit straight.[22]

By the early 1970s, as Brabham team owner Bernie Ecclestone started to marshal the collective bargaining power of the Formula One Constructors Association (FOCA), Monaco was prestigious enough to become an early bone of contention. Historically the number of cars permitted in a race was decided by the race organiser, in this case the ACM, which had always set a low number of around 16. In 1972 Ecclestone started to negotiate deals which relied on FOCA guaranteeing at least 18 entrants for every race. A stand-off over this issue left the 1972 race in jeopardy until the ACM gave in and agreed that 26 cars could participate – the same number permitted at most other circuits. Two years later, in 1974, the ACM got the numbers back down to 18.[29]

Because of its tight confines, slow average speeds and punishing nature, Monaco has often thrown up unexpected results. In the 1982 race René Arnoux led the first 15 laps, before retiring. Alain Prost then led until four laps from the end, when he spun off on the wet track, hit the barriers and lost a wheel, giving Riccardo Patrese the lead. Patrese himself spun with only a lap and a half to go, letting Didier Pironi through to the front, followed by Andrea de Cesaris. On the last lap, Pironi ran out of fuel in the tunnel, but De Cesaris also ran out of fuel before he could overtake. In the meantime, Patrese had bump-started his car and went through to score his first Grand Prix win.[30]

In 1983 the ACM became entangled in the disagreements between Fédération Internationale du Sport Automobile (FISA) and FOCA. The ACM, with the agreement of Bernie Ecclestone, negotiated an individual television rights deal with ABC in the United States. This broke an agreement enforced by FISA for a single central negotiation of television rights. Jean-Marie Balestre, president of FISA, announced that the Monaco Grand Prix would not form part of the Formula One world championship in 1985. The ACM fought their case in the French courts. They won the case and the race was eventually reinstated.[29]

Prost/Senna era

For the decade from 1984 to 1993 the race was won by only two drivers, arguably the two best drivers in Formula One at the time[31][32] – Frenchman Alain Prost and Brazilian Ayrton Senna. Prost, already a winner of the support race for Formula Three cars in 1979, took his first Monaco win at the 1984 race. The race started 45 minutes late after heavy rain. Prost led briefly before Nigel Mansell overtook him on lap 11. Mansell crashed out five laps later, letting Prost back into the lead. On lap 27, Prost led from Ayrton Senna's Toleman and Stefan Bellof's Tyrrell. Senna was catching Prost and Bellof was catching both of them in the only naturally aspirated car in the race. However, on lap 31, the race was controversially stopped with conditions deemed to be undriveable. Later, FISA fined the clerk of the course, Jacky Ickx, $6,000 and suspended his licence for not consulting the stewards before stopping the race.[33] The drivers received only half of the points that would usually be awarded, as the race had been stopped before two-thirds of the intended race distance had been completed.[34]

Prost won 1985 after polesitter Senna retired with a blown Renault engine in his Lotus after over-revving it at the start, and Michele Alboreto in the Ferrari retook the lead twice, but he went off the track at Sainte-Devote, where Brazilian Nelson Piquet and Italian Riccardo Patrese had a huge accident only a few laps previously and oil and debris littered the track. Prost passed Alboreto, who retook the Frenchman, and then he punctured a tyre after running over bodywork debris from the Piquet/Patrese accident, which dropped him to 4th. He was able to pass his Roman countrymen Andrea De Cesaris and Elio de Angelis, but finished 2nd behind Prost. The French Prost dominated 1986 after starting from pole position, a race where the Nouvelle Chicane had been changed on the grounds of safety.[35]

Senna holds the record for the most victories in Monaco, with six, including five consecutive wins between 1989 and 1993, as well as eight podium finishes in ten starts. His 1987 win was the first time a car with an active suspension had won a Grand Prix. He won this race after Briton Nigel Mansell in a Williams-Honda went out with a broken exhaust. His win was very popular with the people of Monaco, and when he was arrested on the Monday following the race, for riding a motorcycle without wearing a helmet, he was released by the officers after they realised who he was.[36] Senna dominated 1988, and was able to get ahead of his teammate Prost while the Frenchman was held up for most of the race by Austrian Gerhard Berger in a Ferrari. By the time Prost got past Berger, he pushed as hard as he could and set a lap some 6 seconds faster than Senna's; Senna then set 2 fastest laps, and while pushing as hard as possible, he touched the barrier at the Portier corner and crashed into the Armco separating the road from the Mediterranean. Senna was so upset that he went back to his Monaco flat and was not heard from until the evening.[37] Prost went on to win for the fourth time.

Senna dominated 1989 while Prost was stuck behind backmarker Rene Arnoux and others; the Brazilian also dominated 1990 and 1991. At the 1992 event Nigel Mansell, who had won all five races held to that point in the season, took pole and dominated the race in his Williams FW14B-Renault. However, with seven laps remaining, Mansell suffered a loose wheel nut and was forced into the pits, emerging behind Ayrton Senna's McLaren-Honda, who was on worn tyres. Mansell, on fresh tyres, set a lap record almost two seconds quicker than Senna's and closed from 5.2 to 1.9 seconds in only two laps. The pair duelled around Monaco for the final four laps but Mansell could find no way past, finishing just two-tenths of a second behind the Brazilian.[38][39] It was Senna's fifth win at Monaco, equalling Graham Hill's record. Senna had a poor start to the 1993 event, crashing in practice and qualifying 3rd behind pole-sitter Prost and the rising German star Michael Schumacher. Both of them beat Senna to the first corner, but Prost had to serve a time penalty for jumping the start and Schumacher retired after suspension problems, so Senna took his sixth win to break Graham Hill's record for most wins at the Monaco Grand Prix. Runner-up Damon Hill commented, "If my father was around now, he would be the first to congratulate Ayrton."[40]

Modern times

The 1994 race was an emotional and tragic affair. It came two weeks after the race at Imola in which Austrian Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna both died from massive head injuries from on-track accidents on successive days. During the Monaco event, Austrian Karl Wendlinger had an accident in his Sauber in the tunnel; he went into a coma and was to miss the rest of the season. The German Michael Schumacher won the 1994 Monaco event.[41] The 1996 race saw Michael Schumacher take pole position before crashing out on the first lap after being overtaken by Damon Hill. Hill led the first 40 laps before his engine expired in the tunnel. Jean Alesi took the lead but suffered suspension failure 20 laps later. Olivier Panis, who started in 14th place, moved into the lead and stayed there until the end of the race, being pushed all the way by David Coulthard. It was Panis's only win, and the last for his Ligier team. Only three cars crossed the finish line, but seven were classified.[42]

Seven-time world champion Schumacher would eventually win the race five times, matching Graham Hill's record. In his appearance at the 2006 event, he attracted criticism when, while provisionally holding pole position and with the qualifying session drawing to a close, he stopped his car at the Rascasse hairpin, blocking the track and obliging competitors to slow down.[43] Although Schumacher claimed it was the unintentional result of a genuine car failure, the FIA disagreed and he was sent to the back of the grid.[44]

In July 2010, Bernie Ecclestone announced that a 10-year deal had been reached with the race organisers, keeping the race on the calendar until at least 2020.[45]

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the FIA announced the 2020 Monaco Grand Prix's postponement, along with the two other races scheduled for May 2020, to help prevent the spread of the virus.[46] However, later the same day the Automobile Club de Monaco confirmed that the Grand Prix was instead cancelled, making 2020 the first time the Grand Prix was not run since 1954.[47]

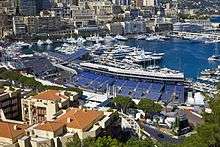

Circuit

The Circuit de Monaco consists of the city streets of Monte Carlo and La Condamine, which includes the famous harbour. It is unique in having been held on the same circuit every time it has been run over such a long period – only the Italian Grand Prix, which has been held at Autodromo Nazionale Monza during every Formula One regulated year except 1980, has a similarly lengthy and close relationship with a single circuit.[48]

The race circuit has many elevation changes, tight corners, and a narrow course that makes it one of the most demanding tracks in Formula One racing.[49] As of 2018, two drivers have crashed and ended up in the harbour, the most famous being Alberto Ascari in 1955.[27][50] Despite the fact that the course has had minor changes several times during its history, it is still considered the ultimate test of driving skills in Formula One, and if it were not already an existing Grand Prix, it would not be permitted to be added to the schedule for safety reasons.[51] Even in 1929, 'La Vie Automobile' magazine offered the opinion that "Any respectable traffic system would have covered the track with <<Danger>> sign posts left, right and centre".[52]

Triple Formula One champion Nelson Piquet was fond of saying that racing at Monaco was "like trying to cycle round your living room", but added that "a win here was worth two anywhere else".[53]

Notably, the course includes a tunnel. The contrast of daylight and gloom when entering/exiting the tunnel presents "challenges not faced elsewhere", as the drivers have to "adjust their vision as they emerge from the tunnel at the fastest point of the track and brake for the chicane in the daylight.".[54]

The fastest-ever qualifying lap was set by Lewis Hamilton in qualifying (Q3) for the 2019 Monaco Grand Prix, at a time of 1m 10.166s.[55]

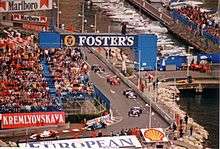

Viewing areas

During the Grand Prix weekend, spectators crowd around the Monaco Circuit. There are a number of temporary grandstands built around the circuit, mostly around the harbour area.[56] The rich and famous spectators often arrive on their boats and the yachts through the harbour. Balconies around Monaco become viewing areas for the race as well. Many hotels and residents cash in on the bird's eye views of the race.[57]

Organization

The Monaco Grand Prix is organised each year by the Automobile Club de Monaco which also runs the Monte Carlo Rally and the Junior Monaco Kart Cup.[58]

The Monaco Grand Prix differs in several ways from other Grands Prix. The practice session for the race is held on the Thursday preceding the race instead of Friday.[59] This allows the streets to be opened to the public again on Friday. Until the late 1990s the race started at 3:30 p.m. local time – an hour and a half later than other European Formula One races. In recent years the race has fallen in line with the other Formula One races for the convenience of television viewers. Also, earlier the event was traditionally held on the week of Ascension Day. It is now always held on the last weekend in May. For many years, the numbers of cars admitted to Grands Prix was at the discretion of the race organisers – Monaco had the smallest grids, ostensibly because of its narrow and twisting track.[60] Only 18 cars were permitted to enter the 1975 Monaco Grand Prix, compared to 23 to 26 cars at all other rounds that year.[61]

The erecting of the circuit takes six weeks, and the removal after the race takes three weeks.[62] There was no podium as such at the race, until 2017. Instead, a section of the track was closed after the race to act as parc fermé, a place where the cars are held for official inspection. The first three drivers in the race left their cars there and walked directly to the royal box where the 'podium' ceremony was held, which was considered a custom for the race.[63] The trophies were handed out before the national anthems for the winning driver and team are played, as opposed to other Grands Prix where the anthems are played first.

Fame

The Monaco Grand Prix is widely considered to be one of the most important and prestigious automobile races in the world alongside the Indianapolis 500 and the 24 Hours of Le Mans.[52][64] These three races are considered to form a Triple Crown of the three most famous motor races in the world. As of 2020, Graham Hill is the only driver to have won the Triple Crown, by winning all three races. The practice session for Monaco overlaps with that for the Indianapolis 500, and the races themselves sometimes clash. As the two races take place on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean and form part of different championships, it is difficult for one driver to compete effectively in both during his career. Juan Pablo Montoya and Fernando Alonso are the only active drivers to have won two of the three events.[65][66]

In awarding its first Gold medal for motorsport to Prince Rainier III, the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) characterised the Monaco Grand Prix as contributing "an exceptional location of glamour and prestige" to motorsport.[5] The Grand Prix has been run under the patronage of three generations of Monaco's royal family: Louis II, Rainier III and Albert II, all of whom have taken a close interest in the race. A large part of the principality's income comes from tourists attracted by the warm climate and the famous casino, but it is also a tax haven and is home to many millionaires, including several Formula One drivers.[67]

Monaco has produced four native Formula One drivers - Louis Chiron, André Testut, Olivier Beretta, and Charles Leclerc[68] - but its tax status has made it home to many drivers over the years, including Gilles Villeneuve and Ayrton Senna. Of the 2006 Formula One contenders, several have property in the principality, including Jenson Button and David Coulthard, who was part owner of a hotel there.[69] Because of the small size of the town and the location of the circuit, drivers whose races end early can usually get back to their apartments in minutes. Ayrton Senna famously retired to his apartment after crashing out of the lead of the 1988 race.[70]

Official names

Unlike other venues, the Monaco Grand Prix has never been sponsored since its first race in 1950. It however, has had multiple names it goes by, namely the following:

- 1950, 1956–1959, 1961, 1964–1965, 1973–1974: Grand Prix Automobile[71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80]

- 1955: Grand Prix d'Europe Automobile[81]

- 1960, 1962: Grand Prix[82]

- 1963: Gd Prix d'Europe[83]

- 1966–1968: Grand Prix Automobile de Monaco[84][85][86]

- 1969–1971, 1975: Monaco[87][88][89][90]

- 1972, 1976–1986, 2014–2015, 2018: Grand Prix Monaco[91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][102][103][104][105]

- 1987–2013, 2016–2017, 2019: Grand Prix de Monaco[106][107][108][109][110][111][112][113][114][115][116][117][118][119][120][121][122][123][124][125][126][127][128][129][130][131][132][133][134][135]

Winners

Repeat winners (drivers)

Drivers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

| Wins | Driver | Years won[23] |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1987, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993 | |

| 5 | 1963, 1964, 1965, 1968, 1969 | |

| 1994, 1995, 1997, 1999, 2001 | ||

| 4 | 1984, 1985, 1986, 1988 | |

| 3 | 1956, 1960, 1961 | |

| 1966, 1971, 1973 | ||

| 2013, 2014, 2015 | ||

| 2008, 2016, 2019 | ||

| 2 | 1950, 1957 | |

| 1955, 1958 | ||

| 1975, 1976 | ||

| 1977, 1979 | ||

| 2000, 2002 | ||

| 2006, 2007 | ||

| 2010, 2012 | ||

| 2011, 2017 |

Repeat winners (constructors)

Teams in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

| Wins | Constructor | Years won[23] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 1984, 1985, 1986, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2005, 2007, 2008 | ||

| 10 | 1952, 1955, 1975, 1976, 1979, 1981, 1997, 1999, 2001, 2017 | ||

| 8 | 1935, 1936, 1937, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2019 | ||

| 7 | 1960, 1961, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1974, 1987 | ||

| 5 | 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1972 | ||

| 4 | 1929, 1930, 1931, 1933 | ||

| 2010, 2011, 2012, 2018 | |||

| 3 | 1932, 1934, 1950 | ||

| 1948, 1956, 1957 | |||

| 1958, 1959, 1962 | |||

| 1971, 1973, 1978 | |||

| 1980, 1983, 2003 | |||

| 2 | 1967, 1982 | ||

| 1994, 1995 | |||

| 2004, 2006 | |||

Repeat winners (engine manufacturers)

Manufacturers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

| Wins | Manufacturer | Years won[23] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 1935, 1936, 1937, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2005, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2019 | ||

| 14 | 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1974, 1977, 1978, 1980, 1982, 1983, 1993, 1994 | ||

| 10 | 1952, 1955, 1975, 1976, 1979, 1981, 1997, 1999, 2001, 2017 | ||

| 6 | 1987, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1992 | ||

| 1995, 2004, 2006, 2010, 2011, 2012 | |||

| 5 | 1958, 1959, 1960, 1961, 1962 | ||

| 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1972 | |||

| 4 | 1929, 1930, 1931, 1933 | ||

| 3 | 1932, 1934, 1950 | ||

| 1948, 1956, 1957 | |||

| 1984, 1985, 1986 | |||

* Between 1998-2005 built by ![]()

** Built by ![]()

*** Built by ![]()

By year

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

Previous circuit configurations

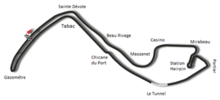

1929–1972

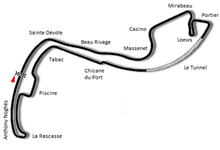

1929–1972 1973–1975

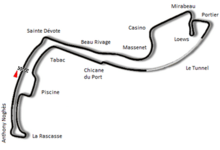

1973–1975 1976–1985

1976–1985 1986–1996

1986–1996

See also

References

- "Top 10 most prestigious races in the world". Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- "The Most Famous Car Races in the World". Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- "3 of the World's Biggest Car Races Are Coming Up – Here's What You Need To Know". Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- Walker, Kate (14 June 2018). "Fernando Alonso Takes Another Shot at a Motorsport Triple Crown". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- "His Serene Highness Prince Rainier of Monte Carlo awarded the first FIA Gold Medal for Motor Sport". Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile. 14 October 2004. Archived from the original on 15 November 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2006.

- "Rules and regulations: Points, classification and race distance". formula1.com. Formula One. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- "Monaco". Retrieved 15 February 2007.

- "Remembering Senna: King of Monaco". Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- Kettlewell, Mike. "Monaco Grand Prix" in Ward, Ian, Executive Editor. The World of Automobiles, Volume 12 (London: Orbis, 1974), p. 1382.

- Hughes, M. 2007. Street theatre 1929. Motor Sport, LXXXIII/3, p. 62

- "The first Grand Prix of Monaco". Motor Sport Magazine (May 1929): 11. Retrieved 4 August 2016.; Kettlewell, p. 1382.

- Kettlewell, p. 1382.

- "Monaco Grand Prix: The Greatest Moments". Thomson Sport. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- Snellman, Leif & Etzrodt, Hans (14 January 2007). "The Golden Era 1933". Retrieved 17 February 2007.

- Tibballs, Geoff (2001). Motor-Racing's Strangest Races. Robson Books. pp. 95–97. ISBN 1-86105-411-4.

- Kettlewell, Mike. "Monaco: Road Racing on the Riviera", in Northey, Tom, editor. World of Automobiles (London: Orbis, 1974), Volume 12, p. 1383.

- Kettlewell, p. 1383.

- The cradle of motorsport www.forix.com Retrieved 6 March 2007

- "History". Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- "1948 Monaco Grand Prix". Motor Sport. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- "Reports of Recent Events". Motor Sport (June 1948): 10. 7 July 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- "Monte Carlo". RacingCircuits.info. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "Standings". Formula 1® - The Official F1® Website.

- The Complete Encyclopedia of Formula One, p. 262 Lines 8–9 Carlton Books Ltd. ISBN 1-85868-515-X

- The Complete Encyclopedia of Formula One, p. 262 Line 10 Carlton Books Ltd. ISBN 1-85868-515-X

- Richard Armstrong. "Graham Hill – All-rounder extraordinary". 8W. Retrieved 23 August 2006.

- "Drivers: Paul Hawkins". GrandPrix.com. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- "Graham Hill – 1962, 1968". Formula1.com. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- Lovell, Terry (2004) Bernie's Game

- Henry, Alan (1985) Brabham, the Grand Prix Cars, p. 237 Osprey ISBN 0-905138-36-8 Henry lists Pironi as having stopped with electrical trouble, but the official results show that the Ferrari driver ran out of fuel.

- "Top 5 rivalries in the history of Formula 1". 21 March 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- https://www.skysports.com/f1/news/12433/11281043/f1s-greatest-rivalries-prost-senna-hamilton-rosberg-have-your-say%7Caccessdate=5 November 2018

- The Chequered Flag p. 320, Lines 55–56 Weidenfeld & Nicolson ISBN 0-297-83550-5

- Spurgeon, Brad (21 May 2015). "When Ayrton Senna Became a Star". The New York Times. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- "Changing tracks: Monte-Carlo". F1 Fanatic. 14 May 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- Grand Prix 1987, p. 60. ISBN 0-908081-27-8

- "Ron Dennis on Senna - Part one: the early years". formula1.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- "Grand Prix results: Monaco GP, 1992". GrandPrix.com. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- Autocourse 1992 pp.150, 153

- Allsop, Derek. Designs on Victory: On The Grand Prix Trail With Benetton. Hutchinson, p. 109, Line 34–35 . ISBN 0-09-178311-9

- "Grand Prix Results: Monaco GP, 1994". GrandPrix.com. 15 May 1994. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Saunders, Will (20 May 2014). "In memory of... 1996 Monaco GP, F1's Wackiest Race". crash.net. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- "BBC SPORT – Motorsport – Formula One – Schumacher in the dock". bbc.co.uk. 28 May 2006.

- "Schumacher is stripped of pole". Formula 1. 27 June 2006. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- "Monaco Grand Prix extends F1 deal by 10 years". BBC Sport. BBC. 28 July 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- "Dutch and Spanish Grands Prix postponed, Monaco cancelled". formula1.com. Liberty Media. 19 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "Monaco announce cancellation of 2020 F1 race due to coronavirus". formula1.com. Liberty Media. 19 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "The Economics of the Formula One Grand Prix of Monaco". 9 July 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- Holt, Sarah (27 May 2007). "As it happened: Monaco Grand Prix". BBC Sport. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- "Drivers: Alberto Ascari". GrandPrix.com. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- In the Driving Seat p. 32, Lines 8–10 Stanley Paul & Co. Ltd. ISBN 0-09-173818-0

- "Why not a Grand Prix in Monte Carlo?". Gale Force of Monaco. Archived from the original on 2 May 2006. Retrieved 9 March 2007.

- Jean-Michel Desnoues; Patrick Camus & Jean-Marc Loubat Formula 1 99 p. 121, Line 6–8. Queen Anne Press. ISBN 1-85291-606-0

- Brad Spurgeon (23 May 2008). "Grand Prix races abound, but there's only one Monaco". nytimes.com. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- "Formula 1 Grand Prix de Monaco 2019 – Qualifying". Formula1.com. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- "Monaco Grand Prix ⋅ Where to Watch". Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- "Monaco Grand Prix weekend: How the rich and famous spend it". Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- "The Automobile Club of Monaco". Retrieved 30 January 2007.

- "Formula One FAQ". Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- "It's a battle of supremacy at Monaco Grand Prix". The Mercury. 25 May 2006. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- Gill, Barrie (ed.) (1976). The World Championship 1975 – John Player Motorsport yearbook 1976. Queen Anne Press Ltd. ISBN 0-362-00254-1.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Allsop, Derek. Designs on Victory: On The Grand Prix Trail With Benetton. Hutchinson, p. 96, Line 4–6. ISBN 0-09-178311-9

- "What The Papers Say About Monaco". PlanetF1.com. 25 May 2009. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- "Indy 500, Sunday May 27, 2007". Top Gear Magazine New Car Supplement 2007. BBC Worldwide. March 2007. p. 30.

- "Triple Crown of Motorsports: Can Juan Pablo Montoya make history?". Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- "Alonso wins le Mans to edge closer to Triple Crown".

- "Yearly Roar". Atlas F1. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- "List drivers by country – Monaco". Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2006. www.f1db.com identifies Testut as Monagasque, although he was born in Lyons, France.

- Sylt, Christian (23 May 2010). "''In the driver's seat: David Coulthard's £30m hotel haul''". Independent.co.uk. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Dorsey, Valerie Lynn (31 October 1988). "Senna sews up world title with Formula One victory". USA Today. p. 11C.

- "1950 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1956 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1957 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1958 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1959 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1961 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1964 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1965 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1973 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1974 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1955 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1962 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1963 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1966 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1967 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1968 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1969 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1970 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1971 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1975 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1972 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1976 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1977 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1978 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1979 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1980 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1981 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1982 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1983 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1984 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1985 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1986 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2014 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2015 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2018 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1987 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1988 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1989 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1990 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1991 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1992 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1993 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1994 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1995 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1996 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1997 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1998 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1999 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2000 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2001 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2002 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2003 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2004 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2005 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2006 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2007 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2008 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2009 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2010 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2011 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2012 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2013 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2016 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2017 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2019 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

Bibliography

- Codling, Stuart (2019). The Life Monaco Grand Prix. Beverly, MA: Motorbooks. ISBN 9780760363744.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Folley, Malcolm (2017). Monaco: Inside F1's Greatest Race. London: Century. ISBN 9781780896168.

- Kettlewell, Mike. "Monaco: Road Racing on the Riviera", in Northey, Tom, editor. World of Automobiles, Volume 12, pp. 1381–4. London: Orbis, 1974.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Monaco Grand Prix. |