San Marino Grand Prix

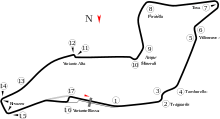

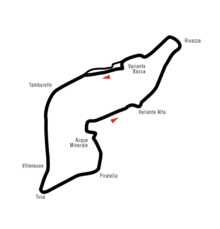

The San Marino Grand Prix (Italian: Gran Premio di San Marino) was a Formula One championship race which was run at the Autodromo Internazionale Enzo e Dino Ferrari in the town of Imola, near the Apennine mountains in Italy, between 1981 and 2006. It was named after nearby San Marino because there already was an Italian Grand Prix held at Monza.[1] In 1980, when Monza was under refurbishment, the Imola track was used for the 51st Italian Grand Prix.

| Autodromo Internazionale Enzo e Dino Ferrari | |

| |

| Race information | |

|---|---|

| Number of times held | 26 |

| First held | 1981 |

| Last held | 2006 |

| Most wins (drivers) | |

| Most wins (constructors) | |

| Circuit length | 4.959 km (3.081 mi) |

| Race length | 307.221 km (191.022 mi) |

| Laps | 62 |

| Last race (2006) | |

| Pole position | |

| |

| Podium | |

| |

| Fastest lap | |

| |

History

Origins

The area around Imola is home to several racing car manufacturers – namely Ferrari, Lamborghini, Maserati, Minardi (later Toro Rosso), Dallara and Stanguellini. Following the Second World War, the town launched a program to try to improve the local economy. Four local motor racing enthusiasts proposed the construction of a new road linking existing public roads, which was used by the local car manufacturers to test their prototypes. Construction began in March 1950. The first test run took place two years later when Enzo Ferrari sent a car to the track and Alberto Ascari ran some demonstration laps.

In April 1953, the first motorcycle races took place at Imola, and the first car race took place in June 1954. In April 1963, the first race with Formula One cars took place at Imola, as a non-championship event, won by Jim Clark for Lotus. A further non-championship event took place at Imola in 1979, which was won by Niki Lauda for Brabham-Alfa Romeo.

In 1980, the Italian Grand Prix moved from the high-speed Monza circuit to Imola (later known as Autodromo Dino Ferrari), as a direct result of 1978's startline pile-up, which claimed the life of the popular Swedish driver Ronnie Peterson. It was won by Nelson Piquet for Brabham-Ford. The following year, the Italian Grand Prix returned to Monza. This left the owners of the Imola circuit without a Grand Prix. They were eager to remain on the calendar, however, and with an Italian Grand Prix already on the calendar, they asked the Automobile Club of San Marino, the motorsport authority of the nearby Republic of San Marino, to apply for their own Grand Prix. Their application was successful and the San Marino Grand Prix was born.[2]

Imola (1981–2006)

1981–1993

The 1981 event saw Canadian Gilles Villeneuve qualify his Ferrari on pole position. He led the race for the first 19 laps until he pitted for fresh tyres. His teammate Didier Pironi inherited the lead but was eventually caught by Nelson Piquet, who eventually won the race with Riccardo Patrese taking second and Carlos Reutemann coming home third. 1982 saw another memorable race; it was boycotted by most of the FOCA teams and was a turning point in Formula One's history. Only 14 cars competed, and after the Renaults of Alain Prost and René Arnoux retired, Ferrari had no competition, and finished first and second. However, Ferrari's triumph was not so clean-cut. Teammates Villeneuve and Pironi battled fiercely on the track, but while the third-placed Tyrrell of Michele Alboreto was far behind, Ferrari ordered their drivers to slow down to minimize the risk of mechanical failure or running out of fuel. Villeneuve believed this order also meant that the cars were to maintain position on the track. However, Pironi believed that the cars were free to race, and passed Villeneuve. Villeneuve believed that Pironi was simply trying to spice up an otherwise dull race, and duly re-passed his teammate, assuming that he would then hold station for the remainder of the race. Thus, Villeneuve failed to protect the inside line going into the Tosa corner on the final lap, and Pironi passed him to take the win. Villeneuve was irate at what he saw as Pironi's betrayal, although opinion inside the Ferrari team was split over the true meaning of the order to slow down. Villeneuve's expression was sullen on the podium, enraged by Pironi's actions. He was quoted afterwards as saying, "I'll never speak to Pironi again in my life." They proved to be prophetic words, as he was still not on speaking terms with his teammate when he died during qualifying for the Belgian Grand Prix two weeks later.

1983 saw Ferrari win again, with Patrick Tambay taking top honors and Riccardo Patrese crashing his Brabham hard at Acquaminerale while battling with Tambay for the lead. 1984 saw Prost win in a McLaren, and 1985 was yet another exciting race. Brazilian Ayrton Senna lead much of the race; but Ferrari driver Stefan Johansson had started in 15th place, and was quickly making up places in only his second drive for the Prancing Horse; he passed Senna at the end of Lap 61 and took the lead. Unfortunately, Johansson had a fuel problem and retired; many others subsequently began to run out of fuel and Prost finished 1st only to be disqualified later when his car was weighed in as 2 kg underweight; victory was then handed to 2nd-placed Italian Elio de Angelis. 1986 saw Prost win yet again in a fuel-starved race. 1987 saw Senna take pole position narrowly from Briton Nigel Mansell; his teammate Nelson Piquet had a huge crash at Tamburello, and although he only received minor injuries, he did not participate in the race due to FIA doctor Sid Watkins declaring the Brazilian unfit for racing. 1988 saw the McLaren duo of Prost and Senna totally dominate; they were both three seconds faster in qualifying than the next-fastest qualifier Piquet in a Lotus.

1989 saw the circuit renamed as Autodromo Enzo e Dino Ferrari to honor the memory of Enzo Ferrari, who had died the year before. It was another notable event which saw Austrian Gerhard Berger crash heavily while going straight on at Tamburello; he was knocked unconscious and the car, after coming to rest and being soaked with fuel, burst into flames. The Austrian survived this crash, and only received burns to his hands and missed the next race, the Monaco Grand Prix. The race was red-flagged and restarted, generating one of the most famous and acrimonious rivalries in sports history. McLaren teammates Prost and Senna made an agreement that whoever got to the slow, long Tosa corner first would stay in front. But as the two teammates started, Prost got the better start and led going into Tamburello. However, Senna got alongside Prost going through the flat-out Villeneuve right-hander and passed the Frenchman into Tosa. Prost was furious, as he saw this as a broken agreement. He followed and attempted to pass Senna on many occasions, eventually going off at the Variante Bassa chicane. Senna won the race, Prost finished second.

In 1990 pole-sitter Senna suffered a puncture on the third lap; leaving Nigel Mansell and Berger to battle hard for the lead. Mansell did a full 360 degree spin on the straight between Tamburello and Villeneuve after Berger forced the Englishman onto the grass; Mansell kept the Ferrari on the road; but because of this spin the V12 engine got grass in it and failed soon after. Riccardo Patrese won the race in a Williams, followed by Berger, who had wrecked his tyres and couldn't keep Patrese from passing him. The 1991 was a rain-soaked event, and Prost spun off on the grass at Rivazza on the parade lap, stalling the engine. Gerhard Berger did the same, but he kept his McLaren going; McLaren finished first and second, with Senna in front of Berger, with Finnish new-boys JJ Lehto finishing on the podium and Mika Häkkinen finishing fifth. 1992 saw the Williams pair of Nigel Mansell and Patrese dominate, and 1993 saw Prost win, now driving a Williams.

1994

The 1994 event is considered to be the blackest weekend in the history of the sport since the 1960 Belgian Grand Prix and it was to mark a watershed of developments to make the sport safer. It was marred by several accidents and two driver deaths over the weekend. On the Friday, during practice, Jordan driver Rubens Barrichello suffered a severe concussion in a collision at the Variante Bassa chicane in which he decelerated violently, went off the banked kerbing and into the fence protecting the crowd from the circuit. The young Brazilian was knocked unconscious for a few minutes. The next day, in qualifying, Simtek driver Roland Ratzenberger crashed at the Villeneuve Corner after his front wing, which he damaged on his first qualifying lap, broke off and Ratzenberger, unable to steer the car into the corner, crashed almost head on into a retaining wall close to the track at nearly 195 mph, suffered a basilar skull fracture and was killed. Then finally, on race day, Benetton driver JJ Lehto and Lotus driver Pedro Lamy collided at the start, with debris flying over the fences injuring eight spectators. Then, on Lap 7, Williams driver Ayrton Senna after a possible mechanical issue with his car, ran off course at the high-speed Tamburello. Senna first came off the track at 325 km/h (195 mph), downshifting twice to 225 km/h (135 mph) before colliding with the wall. Although the accident looked heavy but seemed survivable, a piece of suspension and the right front wheel came off, these items both hit and pierced Senna's helmet at extremely high speeds and caused critical head injuries; the triple-world champion Brazilian died from his injuries at a hospital in Bologna hours later. Later in the race, a wheel from Michele Alboreto's Minardi came off while he was exiting the pitlane; it hit and injured 4 mechanics from Ferrari and Lotus. German Michael Schumacher won the race, with Ferrari temporary replacement Nicola Larini finishing second, but there were no celebrations at all. After these tragic events, Tamburello's flat-out left was changed to a chicane and a right-hander known as the Villenueve curve. These modifications forced the drivers to slow down, therefore made the track much safer.

The reaction to these tragedies towards the sport itself was stunning. Not only had two drivers been killed, one being a triple World Champion, but these were the first fatalities in eight years, and the first at a race meeting in twelve years. Fatalities up until the end of the 1982 season were commonplace; 1 or 2 drivers were killed every season. Much stronger and more efficient materials (such as carbon fibre) in the cars' construction and an increase in track and driver safety over the years meant that fatalities became considerably less frequent. As of February 2019, aside from Senna and Ratzenberger, the only other F1-related fatalities since 1983 were Elio de Angelis during a test session at Circuit Paul Ricard in 1986, and Jules Bianchi during the 2014 Japanese Grand Prix. Minor injuries were usually the worst a driver received in even big accidents, such as Nelson Piquet's accident in 1987 and Gerhard Berger's in 1989. But after this disastrous 1994 event, many circuits were temporarily modified during the season to make them slower, particularly the fearsome Eau Rouge corner at the Spa-Francorchamps circuit in Belgium, which was made into a temporary chicane. The regulations for the cars' design were changed throughout the season, and a raft of changes were to follow for the next season.

1995–2006

For 1995, the Tamburello and Villeneuve corners - which had seen a number of heavy shunts over the years - were altered from flat-out sweeping bends into slower chicanes, and the Variante Bassa was straightened. It was also the catalyst to changes being made to other circuits, and the sport as a whole, in an attempt to make it safer. That year and the next saw Damon Hill win, and 1998 saw Briton David Coulthard take a marginal victory while his Mercedes engine was failing. 1999 to 2004 saw a romp of victories by Michael Schumacher, with the exception of 2001 which was won by his brother Ralf. 2000 featured dominance from Mika Häkkinen and Schumacher, the Finn dropped back after hitting a piece of debris, losing time and having a slower pit stop meaning the German was able to come out on top. 2004 saw BAR driver Jenson Button take a surprise pole position from the dominant Ferrari pair of Schumacher and Barrichello: Button finished second in the race behind Schumacher, who won 13 races that year. 2005 was won by Spaniard Fernando Alonso; and in 2006 Schumacher won for the seventh time, while Japanese driver Yuji Ide caused an accident, which flipped the car of Dutchman Christijan Albers, which cost him his FIA superlicense.

On 29 August 2006 it was announced that the race would be dropped from the calendar for the 2007 season to make room for the Belgian Grand Prix. It has not featured since.[3]

In contrast to motorbike racing, where there have been riders from San Marino, such as Manuel Poggiali and Alex De Angelis, no San Marinese drivers ever competed in the Grand Prix. Italians Elio de Angelis and Riccardo Patrese won in 1985 and 1990, respectively. Michael Schumacher won the race seven times and Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost both won it three times. Williams and Ferrari have both won eight times and McLaren six times.

Imola would return to the F1 race calendar in 2020 it did so under the name of the Emilia-Romagna Grand Prix as opposed to being named after San Marino.[4]

Official names and sponsors

- 1988: Kronenbourg Gran Premio di San Marino[5]

- 1989: Gran Premio Kronenbourg di San Marino[6]

- 1990-1991, 1993–1998, 2002: Gran Premio di San Marino (no official sponsor)[7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15]

- 1992: Gran Premio Iceberg di San Marino[16]

- 1999–2001: Gran Premio Warsteiner di San Marino[17]

- 2003–2006: Gran Premio Foster's di San Marino[18]

Winners of the San Marino Grand Prix

Repeat winners (drivers)

| Wins | Driver | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | 1994, 1999, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2006 | |

| 3 | 1988, 1989, 1991 | |

| 1984, 1986, 1993 | ||

| 2 | 1987, 1992 | |

| 1995, 1996 |

Repeat winners (constructors)

| Wins | Constructor | Years won | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 1982, 1983, 1999, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2006 | ||

| 1987, 1990, 1992, 1993, 1995, 1996, 1997, 2001 | |||

| 6 | 1984, 1986, 1988, 1989, 1991, 1998 | ||

Repeat winners (engine manufacturers)

| Wins | Manufacturer | Years won | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 1982, 1983, 1999, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2006 | ||

| 1985, 1990, 1992, 1993, 1995, 1996, 1997, 2005 | |||

| 4 | 1987, 1988, 1989, 1991 | ||

| 2 | 1984, 1986 | ||

| 1981, 1994 | |||

* Built by Porsche

** Built by Cosworth

By year

All San Marino Grands Prix were held at Imola.

Deaths during the San Marino Grand Prix

- Roland Ratzenberger, died in a crash at Villeneuve Corner during qualifying for the 1994 Grand Prix on 30 April 1994.

- Ayrton Senna, died in a crash at Tamburello while leading the race on 1 May 1994.

References

- CIRCUITS: IMOLA (AUTODROMO ENZO & DINO FERRARI) GrandPrix.com

- "San Marino Grand Prix". Motor Sport. Motor Sport. 52 (6): 42. June 1981. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- "San Marino loses Grand Prix race". BBC Sport. 29 August 2006. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- "Formula 1 adds Portimao, Nurburgring and 2-day event in Imola to 2020 race calendar". www.formula1.com. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- "1988 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- Mitchell, Malcolm. "1989 Formula 1 Programmes - The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1990 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1991 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1993 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1994 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1995 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1996 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1997 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "1998 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- "2002 Formula 1 World Championship Programmes | The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- Mitchell, Malcolm. "1992 Formula 1 Programmes - The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- Mitchell, Malcolm. "1999 Formula 1 Programmes - The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

- Mitchell, Malcolm. "2006 Formula 1 Programmes - The Motor Racing Programme Covers Project". www.progcovers.com.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to San Marino Grand Prix. |