Chinese swords

Historically, all Chinese swords are classified into two types, jian and dao. Jians are double-edged straight swords while daos are single-edged, and mostly curved from the Song dynasty forward. The jian has been translated at times as a long sword, and the dao a saber or a knife. Bronze jians appeared during the mid-third century BC and switched to wrought iron and steel during the late Warring States period. Other than specialized weapons like the Divided Dao, Chinese swords are usually 70–110 cm (28–43 in) in length, although longer swords have been found on occasion.[1] Outside of China, Chinese swords were also used in Japan from the third to the sixth century AD, but were replaced with Korean and native Japanese swords by the middle Heian era.[2]

Bronze age: Shang dynasty (c. 1600 BC–c. 1046 BC) to Spring and Autumn period (771–476 BC)

Knives were found in Fu Hao's tomb, dated c. 1200 BC.[3]

Bronze jians appeared during the Western Zhou. The blades were a mere 28 to 46 cm long. These short stabbing weapons were used as a last defense when all other options had failed.[4]

By the late Spring and Autumn period, jians lengthened to about 56 cm. At this point at least some soldiers used the jian rather than the dagger-axe due to its greater flexibility and portability.[4] China started producing steel in the 6th century BC, but it was not until later on that iron and steel implements were produced in useful amounts.[5] By around 500 BC however the sword and shield combination began to be regarded as superior to the spear and dagger-axe.[6]

Warring States period (475–221 BC)

Iron and steel swords of 80 to 100 cm in length appeared during the mid Warring States period in the states of Chu, Han, and Yan. The majority of weapons were still made of bronze but iron and steel weapons were starting to become more common.[5] By the end of the 3rd century BC, the Chinese had learned how to produce quench-hardened steel swords, relegating bronze swords to ceremonial pieces.[7]

The Zhan Guo Ce states that the state of Han made the best weapons, capable of cleaving through the strongest armour, shields, leather boots and helmets.[8]

Qin dynasty (221–206 BC)

Sword dances are mentioned to be a thing shortly after the end of the Qin dynasty.[9] Swords up to 110 cm in length began to appear.[10]

- Warring States bronze jians

Warring States bronze jian

Warring States bronze jian

Qin dynasty jian

Qin dynasty jian Qin jian

Qin jian Qin jian

Qin jian

Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD)

The jian was mentioned as one of the "Five Weapons" during the Han dynasty, the other four being dao, spear, halberd, and staff. Another version of the Five Weapons lists the bow and crossbow as one weapon, the jian and dao as one weapon, in addition to halberd, shield, and armour.[11]

The jian was a popular weapon during the Han era and there emerged a class of swordsmen who made their living through fencing. Sword fencing was also a popular pastime for aristocrats. A 37 chapter manual known as the Way of the Jian is known to have existed, but is no longer extant. South and central China were said to have produced the best swordsmen.[12]

There existed a weapon called the "Horse Beheading Jian", so called because it was supposedly able to cut off a horse's head.[13] However, another source says that it was an execution tool used on special occasions rather than a military weapon.[14]

Daos with ring pommels also became widespread as a cavalry weapon during the Han era. The dao had the advantage of being single edged, which meant the dull side could be thickened to strengthen the sword, making it less prone to breaking. When paired with a shield, the dao made for a practical replacement for the jian, hence it became the more popular choice as time went on. After the Han, sword dances using the dao rather than the jian are mentioned to have occurred. Archaeological samples range from 86 to 114 cm in length.[15]

An account of Duan Jiong's tactical formation in 167 AD specifies that he arranged "…three ranks of halberds (長鏃 changzu), swordsmen (利刃 liren) and spearmen (長矛 changmao), supported by crossbows (強弩 qiangnu), with light cavalry (輕騎 jingji) on each wing."[16]

Han jians

Han jians Han jian and dao

Han jian and dao Han jian

Han jian Han jian and scabbard

Han jian and scabbard

Three Kingdoms (184/220–280)

Swords of idiosyncratic sizes are mentioned. One individual named Chen apparently wielded a great sword over two meters in length.[17]

Sun Quan's wife had over a hundred female attendants armed with daos.[18]

By the end of the Three Kingdoms the dao had completely overtaken the jian as the primary close combat weapon.[19] The lighter and less durable double edged jian entered the domain of court dancers, officials, and expert warriors.[20]

Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589)

In the 6th century, Qimu Huaiwen introduced to Northern Qi the process of 'co-fusion' steelmaking, which used metals of different carbon contents to create steel. Apparently, daos made using this method were capable of penetrating 30 armour lamellae. It's not clear if the armour was of iron or leather.

Huaiwen made sabres [dao 刀] of 'overnight iron' [su tie 宿鐵]. His method was to anneal [shao 燒] powdered cast iron [sheng tie jing 生鐵精] with layers of soft [iron] blanks [ding 鋌, presumably thin plates]. After several days the result is steel [gang 剛]. Soft iron was used for the spine of the sabre, He washed it in the urine of the Five Sacrificial Animals and quench-hardened it in the fat of the Five Sacrificial Animals: [Such a sabre] could penetrate thirty armour lamellae [zha 札]. The 'overnight soft blanks' [Su rou ting 宿柔鋌] cast today [in the Sui period?] by the metallurgists of Xiangguo 襄國 represent a vestige of [Qiwu Huaiwen's] technique. The sabres which they make are still extremely sharp, but they cannot penetrate thirty lamellae.[21]

Tang dynasty (618–907)

The dao was separated into four categories during the Tang dynasty. These were the Ceremonial Dao, Defense Dao, Cross Dao, and Divided Dao. The Ceremonial Dao was a court item usually decorated with gold and silver. It was also known as the "Imperial Sword". The Defense Dao does not have any specifications but its name is self-explanatory. The Cross Dao was a waist weapon worn on the belt, hence its older name, the Belt Dao. It was often carried as a sidearm by crossbowmen.[22] The Divided Dao, also called a Long Dao (long saber), was a cross between a polearm and a saber. It consisted of a 91 cm blade fixed to a long 120 cm handle ending in an iron butt point, although exceptionally large weapons reaching 3 meters in length and weighing 10.2 kg have been mentioned.[23] Divided daos were wielded by elite Tang vanguard forces and used to spearhead attacks.[13]

In one army, there are 12,500 officers and men. Ten thousand men in eight sections bearing Belt Daos; Two thousand five hundred men in two sections with Divided Daos.[13]

— Taibai Yinjing

Song dynasty (960–1279)

Some warriors and bandits duel wielded daos to break deadlocks in confined terrain during the late Song dynasty.[24]

According to the Xu Zizhi Tongjian Changbian, written in 1183, the "Horse Beheading Dao" (zhanmadao) was a two handed saber with a 93.6 cm blade, 31.2 cm hilt, and ring pommel.[25]

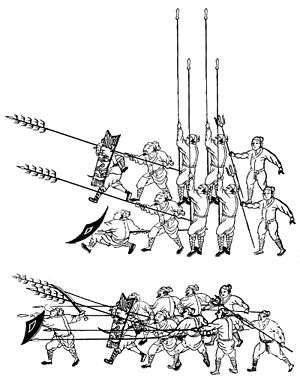

Song soldiers carrying daos

Song soldiers carrying daos Liao and Jin swords

Liao and Jin swords

Yuan dynasty (1279–1368)

Under the Yuan dynasty, the jian experienced a resurgence and was used more often.[26]

Ming dynasty (1368–1644)

The dao continued to fill the role of the basic close combat weapon.[27] The jian fell out of favor again in the Ming era but saw limited use by a small number of arms specialists. It was otherwise known for its qualities as a marker of scholarly refinement.[26]

The "Horse Beheading Dao" was described in Ming sources as a 96 cm blade attached to a 128 cm shaft, essentially a glaive. It's speculated that the Swede Frederick Coyett was talking about this weapon when he described Zheng Chenggong's troops wielding "with both hands a formidable battle-sword fixed to a stick half the length of a man".[28]

Some were armed with bows and arrows hanging down their backs ; others had nothing save a shield on the left arm and a good sword in the right hand ; while many wielded with both hands a formidable battle-sword fixed to a stick half the length of a man. Everyone was protected over the upper part of the body with a coat of iron scales, fitting below one another like the slates of a roof; the arms and legs being left bare. This afforded complete protection from rifle bullets (mistranslation-should read "small arms") and yet left ample freedom to move, as those coats only reached down to the knees and were very flexible at all the joints. The archers formed Koxinga's best troops, and much depended on them, for even at a distance they contrived to handle their weapons with so great skill that they very nearly eclipsed the riflemen. The shield bearers were used instead of cavalry. Every tenth man of them is a leader, who takes charge of, and presses his men on, to force themselves into the ranks of the enemy. With bent heads and their bodies hidden behind the shields, they try to break through the opposing ranks with such fury and dauntless courage as if each one had still a spare body left at home. They continually press onwards, notwithstanding many are shot down ; not stopping to consider, but ever rushing forward like mad dogs, not even looking round to see whether they are followed by their comrades or not. Those with the sword-sticks—called soapknives by the Hollanders—render the same service as our lancers in preventing all breaking through of the enemy, and in this way establishing perfect order in the ranks ; but when the enemy has been thrown into disorder, the Sword-bearers follow this up with fearful massacre amongst the fugitives.[29]

— Frederick Coyett

Qi Jiguang deployed his soldiers in a 12-man 'mandarin duck' formation, which consisted of four pikemen, two men carrying daos with a great and small shield, two 'wolf brush' wielders, a rearguard officer, and a porter.[30]

Ming dao

Ming dao Ming soldiers carrying a dao and jian

Ming soldiers carrying a dao and jian Ming soldier carrying a jian

Ming soldier carrying a jian

Ming-Qing sword types

| Image | Name | Era | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Butterfly sword | Sometimes called butterfly knives in English. It was originally from southern China, though it has seen use in the north. It is usually wielded in pairs, and has short dao (single-edged blade), with a length is approximately that of the forearm. This allows for easy concealment within the sleeves or inside boots, and for greater manoeuvrability to spin and rotate in close-quarters fighting. | |

| Changdao | Ming dynasty | A type of anti-cavalry sword used in China during the Ming dynasty. Sometimes called miao dao (a similar but more recent weapon), the blade greatly resembles a Japanese ōdachi in form. | |

|

Dadao | Also known as the Chinese great sword. Based on agricultural knives, dadao have broad blades generally between two and three feet long, long hilts meant for "hand and a half" or two-handed use, and generally a weight-forward balance. | |

|

Hook sword | The hook sword is an exotic Chinese weapon traditionally associated with Northern styles of Chinese martial arts, but now often practised by Southern styles as well. | |

|

Jian | The jian is a double-edged straight sword used during the last 2,500 years in China. The first Chinese sources that mention the jian date to the 7th century BC during the Spring and Autumn period;[31] one of the earliest specimens being the Sword of Goujian.

Historical one-handed versions have blades varying from 45 to 80 centimeters (17.7 to 31.5 inches) in length. The weight of an average sword of 70-centimeter (28-inch) blade-length would be in a range of approximately 700 to 900 grams (1.5 to 2 pounds). There are also larger two-handed versions used for training by many styles of Chinese martial arts. In Chinese folklore, it is known as the "Gentleman of Weapons" and is considered one of the four major weapons, along with the gun (staff), qiang (spear), and the dao. | |

|

Liuyedao | The liuye dao, or "willow leaf saber", is a type of dao that was commonly used as a military sidearm for both cavalry and infantry during the Ming and Qing dynasties. This weapon features a moderate curve along the length of the blade. This reduces thrusting ability (though it is still fairly effective at same) while increasing the power of cuts and slashes. | |

| Miaodao | Republican era | A Chinese two-handed dao or saber of the Republican era, with a narrow blade of up to 1.2 meters or more and a long hilt. The name means "sprout saber", presumably referring to a likeness between the weapon and a newly sprouted plant. While the miaodao is a recent weapon, the name has come to be applied to a variety of earlier Chinese long sabers, such as the zhanmadao and changdao. Along with the dadao, miaodao were used by some Chinese troops during the Second Sino-Japanese War. | |

| Nandao | Nandao is a kind of sword that is nowadays used mostly in contemporary wushu exercises and forms. It is the southern variation of the "northern broadsword", or Beidao. Its blade bears some resemblance to the butterfly sword, also a southern Chinese single-bladed weapon; the main difference is the size, and the fact that the butterfly swords are always used in pairs | ||

_MET_DP-834-001.jpg) |

Niuweidao | Late Qing dynasty | A type of Chinese saber (dao) of the late Qing dynasty. It was primarily a civilian weapon, as imperial troops were never issued it. |

| Piandao | Late Ming dynasty | A type of Chinese sabre (dao) used during the late Ming dynasty. A deeply curved dao meant for slashing and draw-cutting, it bore a strong resemblance to the shamshir and scimitar. A fairly uncommon weapon, it was generally used by skirmishers in conjunction with a shield. | |

| Wodao | Ming dynasty | A Chinese sword from the Ming dynasty. Apparently influenced by Japanese sword design, it bears a strong resemblance to a tachi or ōdachi in form: extant examples show a handle approximately 25.5 cm long, with a gently curved blade 80 cm long. | |

| Yanmaodao | Late Ming—Qing dynasties | The yanmao dao, or "goose quill saber", is a type of dao made in large numbers as a standard military weapon from the late Ming dynasty through the end of the Qing dynasty. It is similar to the earlier zhibei dao, is largely straight, with a curve appearing at the center of percussion near the blade's tip. This allows for thrusting attacks and overall handling similar to that of the jian, while still preserving much of the dao's strengths in cutting and slashing. | |

| Zhanmadao | Song dynasty | A single edged long broad bladed sword with a long handle suitable for two-handed use. Dating to 1072, it was used as an anti-cavalry weapon. | |

| This list is incomplete. There are many more types of both jian and dao |

See also

- Chinese swordsmanship

- Chinese armour

- Chinese siege weapons

- Weapons and armor in Chinese mythology

References

- Wagner, Donald B. (1993). Iron and Steel in Ancient China. New York, New York: E. J. Brill. pp. 191–199. ISBN 90-04-06234-3.

- Sugawara, Tetsutaka; Lujian Xing (1996). Aikido and Chinese Martial Arts: Its Fundamental Relations Vol. 1. Japan Publications Trading. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0-87040-934-4.

- Lorge 2011, p. 21.

- Lorge 2011, p. 36.

- Lorge 2011, p. 37.

- Peers 2006, p. 31.

- Wagner 1996, p. 197.

- Peers 2013, p. 60.

- Lorge 2011, p. 62.

- Peers 2006, p. 44.

- Lorge 2011, p. 68.

- Lorge 2011, p. 69.

- Lorge 2011, p. 103.

- Zhan Ma Dao (斬馬刀), retrieved 15 April 2018

- Lorge 2011, p. 69-70.

- Crespigny 2017, p. 157.

- Lorge 2011, p. 80.

- Lorge 2011, p. 86.

- Lorge 2011, p. 78.

- Lorge 2011, p. 83.

- Wagner 2008, p. 256.

- Graff 2016, p. 64.

- Zhan Ma Dao (斬馬刀), retrieved 15 April 2018

- Lorge 2011, p. 148.

- Zhan Ma Dao (斬馬刀), retrieved 15 April 2018

- Lorge 2011, p. 180.

- Lorge 2011, p. 177.

- Zhan Ma Dao (斬馬刀), retrieved 15 April 2018

- Coyet 1975, p. 51.

- Peers 2006, p. 203-204.

- Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 41.

Bibliography

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Coyet, Frederic (1975), Neglected Formosa: a translation from the Dutch of Frederic Coyett's Verwaerloosde Formosa

- Crespigny, Rafe de (2017), Fire Over Luoyang: A History of the Later Han Dynasty, 23-220 AD, Brill

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Routledge

- Graff, David A. (2016), The Eurasian Way of War: Military practice in seventh-century China and Byzantium, Routledge

- Kitamura, Takai (1999), Zhanlue Zhanshu Bingqi: Zhongguo Zhonggu Pian, Gakken

- Lorge, Peter A. (2011), Chinese Martial Arts: From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-87881-4

- Lorge, Peter (2015), The Reunification of China: Peace through War under the Song Dynasty, Cambridge University Press

- Peers, C.J. (1990), Ancient Chinese Armies: 1500-200BC, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (1992), Medieval Chinese Armies: 1260-1520, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (1995), Imperial Chinese Armies (1): 200BC-AD589, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (1996), Imperial Chinese Armies (2): 590-1260AD, Osprey Publishing

- Peers, C.J. (2006), Soldiers of the Dragon: Chinese Armies 1500 BC - AD 1840, Osprey Publishing Ltd

- Peers, Chris (2013), Battles of Ancient China, Pen & Sword Military

- Perdue, Peter C. (2005), China Marches West, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

- Robinson, K.G. (2004), Science and Civilization in China Volume 7 Part 2: General Conclusions and Reflections, Cambridge University Press

- Swope, Kenneth M. (2009), A Dragon's Head and a Serpent's Tail: Ming China and the First Great East Asian War, 1592–1598, University of Oklahoma Press

- Wood, W. W. (1830), Sketches of China

- Wagner, Donald B. (1996), Iron and Steel in Ancient China, E.J. Brill

- Wagner, Donald B. (2008), Science and Civilization in China Volume 5-11: Ferrous Metallurgy, Cambridge University Press

- Wright, David (2005), From War to Diplomatic Parity in Eleventh Century China, Brill

- Late Imperial Chinese Armies: 1520-1840 C.J. Peers, Illustrated by Christa Hook, Osprey Publishing «Men-at-arms», ISBN 1-85532-655-8

External links

- http://www.shadowofleaves.com/Chinese_Sword_History.htm

- http://www.chinesesword.net/Swordplay/Swordplay1E.htm