Megalith

A megalith is a large pre-historic stone that has been used to construct a structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. There are over 35,000 in Europe alone, ranging from Sweden to the Mediterranean sea.[1]

The word was first used in 1849 by the British antiquarian Algernon Herbert in reference to Stonehenge[2][3] and derives from the Ancient Greek. Most extant megaliths were erected between the Neolithic period (although earlier Mesolithic examples are known) through the Chalcolithic period and into the Bronze Age.[4]

Types and definitions

While "megalith" is often used to describe a single piece of stone, it also can be used to denote one or more rocks hewn in definite shapes for special purposes.[5] It has been used to describe structures built by people from many parts of the world living in many different periods. The most widely known megaliths are not tombs.[6]

Single stones

- Menhir

- Menhir is the name used in Western Europe for a single upright stone erected in prehistoric times; sometimes called a "standing stone".[8]

- Monolith

- Any single standing stone erected in prehistoric times.[9] Sometimes synonymous with "megalith" and "menhir"; for later periods, the word monolith is more likely to be used to describe single stones.

- Capstone style

- Single megaliths placed horizontally, often over burial chambers, without the use of support stones.[10]

Multiple stones

- Alignments

- Multiple megaliths placed in relation to each other with intention. Often placed in rows or spirals. Some alignments, such as the Carnac Stones in Brittany, France consist of thousands of stones.

- Megalithic walls

- Also called Cyclopean walls[11]

- Stone circles

- In most languages stone circles are called "cromlechs" (a word in the Welch language); the word "cromlech" is sometimes used with that meaning in English.

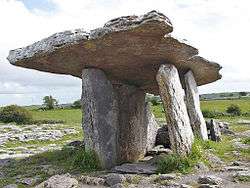

- Dolmen

- A Dolmen is a megalithic form created by placing a large capstone on two or more support stones creating a chamber below, sometimes closed in on one or more sides. Often used as a tomb or burial chamber.

- Cist

- A Cist is a small stone-built coffin-like box or ossuary used to hold the bodies of the dead. Burials are megalithic forms very similar to dolmens in structure. These type of burials were completely underground. There were single- and multiple-chambered cists.

- Portals, doors, and gates

Timeline

Mesolithic

- c. 9500 BC: Construction in Asia Minor (Göbekli Tepe); from proto-Hattian or else a yet-to-be-discovered culture (the oldest religious structure in the world).

- c. 7400 BC: A 12 m long monolith probably weighing around 15,000 kg found submerged 40 m under water in the Strait of Sicily south-west of Sicily. Its origin and purpose are unknown.[12]

Neolithic

- c. 7000 BC: Construction in proto-Canaanite Israel (Atlit Yam). Possibly first standing stones in Portugal.[13]

- c. 6000 BC: Constructions in Portugal (Almendres Cromlech, Évora)

- c. 5000 BC: Emergence of the Atlantic Neolithic period, the age of agriculture along the western shores of Europe during the sixth millennium BC pottery culture of La Almagra, Spain nearby, perhaps precedent from Africa.

- c. 4800 BC: Constructions in Brittany, France[14] (Barnenez) and Poitou (Bougon).

- c. 4500 BC: Constructions in south Egypt (Nabta Playa).

- c. 4300 BC: Constructions in south Spain (Dolmen de Alberite, Cádiz).

- c. 4000 BC: Constructions in Brittany (Carnac), Portugal (Great Dolmen of Zambujeiro, Évora), France (central and southern), Corsica, Spain (Galicia), England and Wales, Constructions in Andalusia, Spain (Villa Martín, Cádiz), Construction in proto-Canaanite Israel c. 4000~3000 BC: Constructions in the rest of the proto-Canaanite Levant, e.g. Rujm el-Hiri and dolmens.

- c. 3700 BC: Constructions in Ireland (Knockiveagh and elsewhere).

- c. 3600 BC: Constructions in Malta (Skorba temples).[15]

- c. 3600 BC: Constructions in England (Maumbury Rings and Godmanchester), and Malta (Ġgantija and Mnajdra temples).

- c. 3500 BC: Constructions in Spain (Málaga and Guadiana), Ireland (south-west), France (Arles and the north), Malta (and elsewhere in the Mediterranean), Belgium (north-east), and Germany (central and south-west).

- c. 3400 BC: Constructions in Sardinia (circular graves), Ireland (Newgrange), Netherlands (north-east), Germany (northern and central) Sweden and Denmark.

- c. 3300 BC: Constructions in France (Carnac stones)

- c. 3200 BC: Constructions in Malta (Ħaġar Qim and Tarxien).

- c. 3100 BC: Constructions in Russia (Dolmens of North Caucasus)

- c. 3000 BC: Constructions in Sardinia (earliest construction phase of the prehistoric altar of Monte d'Accoddi), France (Saumur, Dordogne, Languedoc, Biscay, and the Mediterranean coast), Spain (Los Millares), Sicily, Belgium (Ardennes), and Orkney, as well as the first henges (circular earthworks) in Britain.

Chalcolithic

- c. 2500 BC: Constructions in Brittany (Le Menec, Kermario and elsewhere), Italy (Otranto), Sardinia, and Scotland (northeast), plus the climax of the megalithic Bell-beaker culture in Iberia, Germany, and the British Isles (stone circle at Stonehenge). With the bell-beakers, the Neolithic period gave way to the Chalcolithic, the age of copper.

- c. 2500 BC: Tombs at Algarve, Portugal.[16] Additionally, a problematic dating (by optically stimulated luminescence) of Quinta da Queimada Menhir in western Algarve indicates "a very early period of megalithic activity in the Algarve, older than in the rest of Europe and in parallel, to some extent, with the famous Anatolian site of Göbekli Tepe"[17]

- c. 2400 BC: The Bell-beaker culture was dominant in Britain, and hundreds of smaller stone circles were built in the British Isles at this time.

Bronze Age

- c. 2000 BC: Constructions in Brittany (Er Grah), Italy : (Bari); Sicily (Cava dei Servi, Cava Lazzaro);, and Scotland (Callanish). The Chalcolithic period gave way to the Bronze Age in western and northern Europe.

- c. 1800 BC: Constructions in Italy (Giovinazzo, in Sardinia started the nuragic civilisation).

- c. 1500 BC: Constructions in Portugal (Alter Pedroso and Mourela).

- c. 1400 BC: Burial of the Egtved Girl in Denmark, whose body is today one of the best-preserved examples of its kind.

- c. 1200 BC: Last vestiges of the megalithic tradition in the Mediterranean and elsewhere come to an end during the general population upheaval known to ancient history as the Invasions of the Sea Peoples. Megalithic construction persisted in Egypt into the Iron Age.[lower-alpha 1]

Present

- Currently, the only known cultures where remains active are in parts of Indonesia.

Geographic distribution of megaliths

Megalithic sites in Turkey

Göbekli Tepe

At a number of sites in southeastern Turkey, ceremonial complexes with large T-shaped megalithic orthostats, dating from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN, c. 9600–7000 cal BC), have been discovered.

At the most famous of these sites, Göbekli Tepe, parts of the oldest level (III) have been C14-dated as far back as to the mid-10th millennium BC (cal).[18] On this level, 20 great stone circles (up to 20 meters in diameter) with standing stones up to 7 meters high have been identified.[19] At least 5 of these circles have so far (as of 2019) been excavated.[20] Many of the standing stones are richly ornamented with carved reliefs of "[b]ears, boars, snakes, foxes, wildcats, aurochs, gazelle, quadruped reptiles, birds, spiders, insects, quadrupeds, scorpions" and other animals; in addition, some of the stones are carved in low profile with stylized human features (arms, hands, loincloths, but no heads).[21][22]

On the younger level (II) rectangular structures with smaller megaliths have been excavated. In the surrounding area, several village sites incorporating elements similar to those of Göbekli Tepe have been identified.[23] Four of these have Göbekli Tepe's characteristic T-shaped standing stones, though only one of them, Nevalı Çori, has so far been excavated.[24] At Göbekli Tepe itself, no traces of habitation have so far been found, nor any trace of agriculture or cultivated plants, though bones of wild animals and traces of wild edible plants, along with many grinding stones, have been unearthed.[25] It is thus assumed that these structures (which have been characterized as the first known ceremonial architecture)[26] were erected by hunter-gatherers.

Göbekli Tepe's oldest structures are about 7,000 years older than the Stonehenge megaliths, although it is doubtful that any of the European megalithic traditions (see below) are derived from them.[27]

Middle Eastern megaliths

Dolmens and standing stones have been found in large areas of the Middle East starting at the Turkish border in the north of Syria close to Aleppo, southwards down to Yemen. They can be encountered in Lebanon, Syria, Iran, Israel, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia. The largest concentration can be found in southern Syria and along the Jordan Rift Valley; these are threatened with destruction. They date from the late Chalcolithic or Early Bronze Age.[28] Megaliths have also been found on Kharg Island and Pirazmian in Iran, at Barda Balka in Iraq.

A semicircular arrangement of megaliths was found in Israel at Atlit Yam, a site that is now under the sea. It is a very early example, dating from the 7th millennium BC.[29]

The most concentrated occurrence of dolmens in particular is in a large area on both sides of the Jordan Rift Valley, with greater predominance on the eastern side. They occur first and foremost on the Golan Heights, the Hauran, and in Jordan, which probably has the largest concentration of dolmen in the Middle East. In Saudi Arabia, only very few dolmen have been identified so far in the Hejaz. They seem, however, to re-emerge in Yemen in small numbers, and thus could indicate a continuous tradition related to those of Somalia and Ethiopia.

The standing stone has a very ancient tradition in the Middle East, dating back from Mesopotamian times. Although not always 'megalithic' in the true sense, they occur throughout the area and can reach 5 metres or more in some cases (such as at Ader in Jordan). This phenomenon can also be traced through many passages from the Old Testament, such as those related to Jacob, the grandson of Abraham, who poured oil over a stone that he erected after his famous dream in which angels climbed to heaven (Genesis 28:10-22). Jacob is also described as putting up stones at other occasions, whereas Moses erected twelve pillars symbolizing the tribes of Israel. The tradition of venerating standing stones continued in Nabatean times and is reflected in, e.g., the Islamic rituals surrounding the Kaaba and nearby pillars. Related phenomena, such as cupholes, rock-cut tombs and circles, also occur in the Middle East.

European megaliths

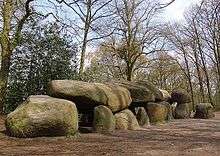

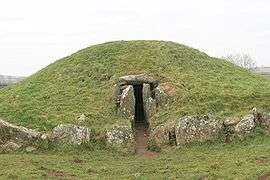

The most common type of megalithic construction in Europe is the portal tomb — a chamber consisting of upright stones (orthostats) with one or more large flat capstones forming a roof. Many of these, though by no means all, contain human remains, but it is debatable whether use as burial sites was their primary function. The megalithic structures in the northwest of France are believed to be the oldest in Europe based on radiocarbon dating.[30] Though generally known as "dolmens," the term most accepted by archaeologists is "portal tomb." However many local names exist, such as anta in Galicia and Portugal, stazzone in Sardinia, hunebed in the Netherlands, Hünengrab in Germany, dysse in Denmark, and cromlech in Wales. It is assumed that most portal tombs were originally covered by earthen mounds.

The second-most-common tomb type is the passage grave. It normally consists of a square, circular, or cruciform chamber with a slabbed or corbelled roof, accessed by a long, straight passageway, with the whole structure covered by a circular mound of earth. Sometimes it is also surrounded by an external stone kerb. Prominent examples include the sites of Brú na Bóinne and Carrowmore in Ireland, Maes Howe in Orkney, and Gavrinis in France.

The third tomb type is a diverse group known as gallery graves. These are axially arranged chambers placed under elongated mounds. The Irish court tombs, British long barrows, and German Steinkisten belong to this group.

Standing stones, or menhirs as they are known in France, are very common throughout Europe, where some 50,000 examples have been noted. Some of these are thought to have an astronomical function as a marker or foresight. In some areas, long and complex "alignments" of such stones exist, the largest known example being located at Carnac in Brittany, France.

In parts of Britain and Ireland a relatively common type of megalithic construction is the stone circle, of which examples include Stonehenge, Avebury, Ring of Brodgar and Beltany. These, too, display evidence of astronomical alignments, both solar and lunar. Stonehenge, for example, is famous for its solstice alignment. Examples of stone circles are also found in the rest of Europe. The circle at Lough Gur, near Limerick in Ireland has been dated to the Beaker period, approximately contemporaneous with Stonehenge. The stone circles are assumed to be of later date than the tombs, straddling the Neolithic and the Bronze Ages.

.jpg)

Tombs

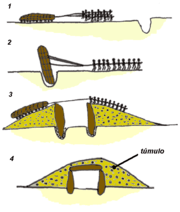

Megalithic tombs are aboveground burial chambers, built of large stone slabs (megaliths) laid on edge and covered with earth or other, smaller stones. They are a type of chamber tomb, and the term is used to describe the structures built across Atlantic Europe, the Mediterranean, and neighbouring regions, mostly during the Neolithic period, by Neolithic farming communities. They differ from the contemporary long barrows through their structural use of stone.

There is a huge variety of megalithic tombs. The free-standing single chamber dolmens and portal dolmens found in Brittany, Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands, Sweden, Wales, and elsewhere consist of a large flat stone supported by three, four, or more standing stones. They were covered by a stone cairn or earth barrow.

In Italy, dolmens can be found especially in Sardinia. There are more than 100 dolmen dating to the Neolithic (3500–2700 BC) and the most famous is called Dolmen di Sa Coveccada (near Mores). During the Bronze Age, the Nuragic civilization built c. 800 Giants' grave, a type of megalithic gallery grave that can be found throughout Sardinia with different structures. The earliest megalithic tombs in Sardinia are the circular graves of the so-called Arzachena culture, also found in Corsica, southern France and eastern Spain.

Dolmens are also in Apulia and in Sicily. In this latter region, they are small structures located in Mura Pregne (Palermo), Sciacca (Agrigento), Monte Bubbonia (Caltanissetta), Butera (Caltanissetta), Cava Lazzaro (Siracusa), Cava dei Servi (Ragusa), Avola (Siracusa), and Argimusco in Montalbano Elicona (Messina). Dating to the Early Bronze Age (2200–1800 BC), the prehistoric Sicilian buildings were covered by a circular mound of earth. In the dolmen of Cava dei Servi, archaeologists found numerous human bone fragments and some splinters of Castelluccian ceramics (Early Bronze Age) which confirmed the burial purpose of the artefact.[31]

Examples with outer areas, not used for burial, are also known. The Court Cairns of southwest Scotland and northern Ireland, the Severn-Cotswold tombs of southwest England and the transepted gallery graves of the Loire region in France share many internal features, although the links between them are not yet fully understood. That they often have antechambers or forecourts is thought to imply a desire on the part of the builders to emphasize a special ritual or physical separation of the dead from the living.

.jpg)

Megalithic tombs appear to have been used by communities for the long-term deposition of the remains of their dead, and some seem to have undergone alteration and enlargement. The organization and effort required to erect these large stones suggest that the societies concerned placed great emphasis on the proper treatment of their dead. The ritual significance of the tombs is supported by the presence of megalithic art carved into the stones at some sites. Hearths and deposits of pottery and animal bone found by archaeologists around some tombs also implies that some form of burial feast or sacrificial rites took place there.

Further examples of megalithic tombs include the stalled cairn at Midhowe in Orkney and the passage grave at Bryn Celli Ddu on Anglesey. There are also extensive grave sites with up to 60 megaliths at Louisenlund and Gryet on the Danish island of Bornholm.[32]

Despite its name, the Stone Tomb in Ukraine was not a tomb but rather a sanctuary.

Other structures

In association with the megalithic constructions across Europe, there are often large earthworks of various designs — ditches and banks (like the Dorset Cursus), broad terraces, circular enclosures known as henges, and frequently artificial mounds such as Silbury Hill in England and Monte d'Accoddi in Sardinia (the prehistoric step pyramid).

Spread of megalithic architecture in Europe

In Europe megaliths are, in general, constructions erected during the Neolithic or late Stone Age and Chalcolithic or Copper Age (4500–1500 BC). The megalithic structures of Malta are believed to be the oldest in Europe. Perhaps the most famous megalithic structure is Stonehenge in England. In Sardinia, in addition to dolmens, menhirs and circular graves there are also more than 8000 megalithic structure made by a Nuragic civilisation, called Nuraghe: buildings similar to towers (sometimes with really complex structures) made using only rocks. They are often near giant's grave or the other megalithic monuments.

The French Comte de Caylus was the first to describe the Carnac stones. Pierre Jean-Baptiste Legrand d'Aussy introduced the terms menhir and dolmen, both taken from the Breton language, into antiquarian terminology. He mistakenly interpreted megaliths as Gallic tombs. In Britain, the antiquarians Aubrey and Stukeley conducted early research into megaliths. In 1805, Jacques Cambry published a book called Monuments celtiques, ou recherches sur le culte des Pierres, précédées d'une notice sur les Celtes et sur les Druides, et suivies d'Etymologie celtiques, where he proposed a Celtic stone cult. This unproven connection between druids and megaliths has haunted the public imagination ever since. In Belgium, there are the Wéris megaliths at Wéris, a little town situated in the Ardennes. In the Netherlands, megalithic structures can be found in the northeast of the country, mostly in the province of Drenthe. Knowth is a passage grave of the Brú na Bóinne neolithic complex in Ireland, dating from c. 3500–3000 BC. It contains more than a third of the total number of examples of megalithic art in all Europe, with over 200 decorated stones found during excavations.

African megaliths

Nabta Playa at the southwest corner of the western Egyptian desert was once a large lake in the Nubian Desert, located 500 miles south of modern-day Cairo.[33] By the 5th millennium BC, the peoples in Nabta Playa had fashioned an astronomical device that accurately marks the summer solstice.[34] Findings indicate that the region was occupied only seasonally, likely only in the summer when the local lake filled with water for grazing cattle.[35] There are other megalithic stone circles in the southwestern desert.

Namoratunga, a group of megaliths dated 300 BC, was used by Cushitic-speaking people as an alignment with star systems tuned to a lunar calendar of 354 days. This discovery was made by B. N. Lynch and L. H. Robins of Michigan State University.[36]

Additionally, Tiya in central Ethiopia has a number old megaliths. Some of these ancient structures feature engravings, and the area is a World Heritage Site. Megaliths are also found within the Valley of Marvels in the East Hararghe area.

Asian megaliths

Megalithic burials are found in Northeast and Southeast Asia. They are found mainly in the Korean Peninsula. They are also found in the Liaoning, Shandong, and Zhejiang in China, the East Coast of Taiwan, Kyūshū and Shikoku in Japan, Đồng Nai Province in Vietnam and South Asia. Some living megalithic traditions are found on the island of Sumba and Nias in Indonesia. The greatest concentration of megalithic burials is in Korea. Archaeologists estimate that there are 15,000 to 100,000 southern megaliths in the Korean Peninsula.[37][38] Typical estimates hover around the 30,000 mark for the entire peninsula, which in itself constitutes some 40% of all dolmens worldwide (see Dolmen).

East Asia

Northern style

Northeast Asian megalithic traditions originated in northeast China, in particular the Liao River basin.[39][40] The practice of erecting megalithic burials spread quickly from the Liao River Basin and into the Korean Peninsula, where the structure of megaliths is geographically and chronologically distinct. The earliest megalithic burials are called "northern" or "table-style" because they feature an above-ground burial chamber formed by heavy stone slabs that form a rectangular cist.[41] An oversized capstone is placed over the stone slab burial chamber, giving the appearance of a table-top. These megalithic burials date to the early part of the Mumun pottery period (c. 1500–850 BC) and are distributed, with a few exceptions, north of the Han River. Few northern-style megaliths in northeast China contain grave goods such as Liaoning bronze daggers, prompting some archaeologists to interpret the burials as the graves of chiefs or preeminent individuals.[42] However, whether a result of grave-robbery or intentional mortuary behaviour, most northern megaliths contain no grave goods.

Southern style

Southern-style megalithic burials are distributed in the southern Korean Peninsula. It is thought that most of them date to the latter part of the Early Mumun or to the Middle Mumun Period.[41][42] Southern-style megaliths are typically smaller in scale than northern megaliths. The interment area of southern megaliths has an underground burial chamber made of earth or lined with thin stone slabs. A massive capstone is placed over the interment area and is supported by smaller propping stones. Most of the megalithic burials on the Korean Peninsula are of the southern type.

As with northern megaliths, southern examples contain few, if any, artifacts. However, a small number of megalithic burials contain fine red-burnished pottery, bronze daggers, polished groundstone daggers, and greenstone ornaments. Southern megalithic burials are often found in groups, spread out in lines that are parallel with the direction of streams. Megalithic cemeteries contain burials that are linked together by low stone platforms made from large river cobbles. Broken red-burnished pottery and charred wood found on these platforms has led archaeologists to hypothesize that these platform were sometimes used for ceremonies and rituals.[43] The capstones of many southern megaliths have 'cup-marks' carvings. A small number of capstones have human and dagger representations.

Capstone style

These megaliths are distinguished from other types by the presence of a burial shaft, sometimes up to 4 m in depth, which is lined with large cobbles.[44] A large capstone is placed over the burial shaft without propping stones. Capstone-style megaliths are the most monumental type in the Korean Peninsula, and they are primarily distributed near or on the south coast of Korea. It seems that most of these burials date to the latter part of the Middle Mumun (c. 700–550 BC), and they may have been built into the early part of the Late Mumun. An example is found near modern Changwon at Deokcheon-ni, where a small cemetery contained a capstone burial (No. 1) with a massive, rectangularly shaped, stone and earthen platform. Archaeologists were not able to recover the entire feature, but the low platform was at least 56×18 m in size.

Southeast Asia

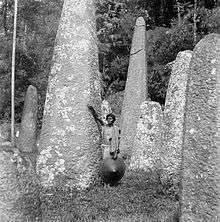

Living megalith culture of Indonesia

The Indonesian archipelago is the host of Austronesian megalith cultures both past and present. Living megalith cultures can be found on Nias, an isolated island off the western coast of North Sumatra, the Batak people in the interior of North Sumatra, on Sumba island in East Nusa Tenggara and also Toraja people from the interior of South Sulawesi. These megalith cultures remained preserved, isolated and undisturbed well into the late 19th century.

Several megalith sites and structures are also found across Indonesia. Menhirs, dolmens, stone tables, and ancestral stone statues were discovered in various sites in Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi, and the Lesser Sunda Islands.

The Cipari megalith site also in West Java displays monoliths, stone terraces, and sarcophagi.[45][46]

Lore Lindu National Park in Central Sulawesi houses ancient megalith relics such as ancestral stone statues, mostly located in the Bada, Besoa and Napu valleys.[47]

South Asia

Megaliths in South Asia are dated before 3000 BC, with recent findings dated back to 5000 BC in southern India.[48] Megaliths are found in almost all parts of South Asia. There is also a broad time evolution with the megaliths in central India and the upper Indus valley where the oldest megaliths are found, while those in the east are of much later date.[49][50] A large fraction of these are assumed to be associated with burial or post burial rituals, including memorials for those whose remains may or may not be available. The case-example is that of Brahmagiri, which was excavated by Wheeler (1975) and helped establish the culture sequence in south Indian prehistory. However, there is another distinct class of megaliths that do not seem to be associated with burials.[51]

In South Asia, megaliths of all kinds are noted; these vary from Menhirs, Rock-cut burial, chamber tomb, dolmens, stone alignment, stone circles and anthropomorphic figures.[52] These are broadly classified into two (potentially overlapping) classes (after Moorti, 1994, 2008): Sepulchral (containing remains of the dead), or memorial stones where mortal remains along with funerary objects are placed; and Non-sepulchral including large patterned placement of stones over a wide area. The 'non-sepulchral' type is associated with astronomy and cosmology in South Asia and in other parts of the world (Menon and Vahia, 2010).[53]

In the context of prehistoric anthropomorphic figures in India, (Rao 1988/1999, Upinder Singh 2008) note that it is unclear what these giant anthropomorphs symbolize. They usually occur in association with megalithic monuments and are located in megalithic burial grounds, and may have been connected with ancestor worship.[54][55]

Melanesian megaliths

Megaliths occur in many parts of Melanesia, mainly in Milne Bay Province, Fiji and Vanuatu. Few excavations has been made and little is known about the structures. The megalith tomb Otuyam at Kiriwina has been dated to be approximately 2,000 years old which indicates that megaliths are an old custom in Melanesia. However very few megaliths have been dated. The constructions have been used for different rituals. For example, tombs, sacrifices and rituals of fecundity. Dance sites exist next to some megaliths. In some places in Melanesia rituals are continued to be held at the sacred megalith sites. The fact that the beliefs are alive is a reason that most excavations have been stopped at the sites.

Micronesian megaliths

Megalithic structures in Micronesia reach their most developed form on the islands of Pohnpei and Kosrae in the Eastern Caroline Islands. On these two islands there was extensive use of prismatic basalt columns to build upland building complexes such as those at Salapwuk on Pohnpei and Menka on Kosrae. These building sites, remote from the ocean, appear to have been abandoned early. Megalithic building then shifted to constructing networks of artificial islands on the coast that supported a multitude of common, royal and religious structures. Dating of the structures is difficult but the complex at Nan Madol on Pohpei was probably inhabited as early as c. 800, probably as an artificial islands, with the more elaborate buildings and religious structures added to the site from 1000–1400 AD.

Modern theories

The purpose

Megaliths were used for a variety of purposes ranging from serving as boundary markers of territory, to a reminder of past events, and to being part of the society's religion.[56] Common motifs including crooks and axes seem to be symbols of political power, much as the crook was a symbol of Egyptian pharaohs. Amongst the indigenous peoples of India, Malaysia, Polynesia, North Africa, North America, and South America, the worship of these stones, or the use of these stones to symbolize a spirit or deity, is a possibility.[57] In the early 20th century, some scholars believed that all megaliths belonged to one global "Megalithic culture"[58] (hyperdiffusionism, e. g. "the Manchester school",[59] by Grafton Elliot Smith and William James Perry), but this has long been disproved by modern dating methods. Nor is it believed any longer that there was a pan-European megalithic culture, although regional cultures existed, even within such small areas as the British Isles. The archaeologist Euan Mackie wrote, "Likewise it cannot be doubted that important regional cultures existed in the Neolithic period and can be defined by different kinds of stone circles and local pottery styles (Ruggles & Barclay 2000: figure 1). No-one has ever been rash enough to claim a nationwide unity of all aspects of Neolithic archaeology!"[60]

Methods of construction

Much scholarship over history has suggested that Stone Age peoples moved the large stones on cylindrical wooden rollers. However, there is some disagreement with this theory, specifically as experiments have indicated that this method is impractical on uneven ground. In some contemporary megalith building cultures, such as in Sumba, Indonesia great emphasis is placed on the social status of moving heavy stones without the relief of rollers. And in the majority of documented contemporary megalithic-building communities, the stones have been placed on timber sledges and dragged without rollers.[61]

Types of megalithic structure

The types of megalithic structure can be divided into two categories, the "polylithic type" and the "monolithic type."[62] Different megalithic structures include:

|

|

Contemporary megalith-building cultures

The Toraja of Indonesia

The megalithic culture of the Toraja people in the mountainous region of South Sulawesi, Indonesia dates back to around 2500–1000 BC, but numerous practitioners still persist today.[64]

The Marapu of Indonesia

In West Sumba, Indonesia, the more than 20,000 followers[65] of the Marapu animist religion construct megalithic tombs by hand. Originally built with slave labor, the large tombs of nobles are now built by a class of dependents who are paid either in animals or cash (an amount equal to $0.65–0.90 per day). The tombs are planned long in advance, with families sometimes going into extreme debt to finance the construction. In 1971, one leading family sacrificed 350 buffalo over the course of a year in order to feed the 1,000 people necessary to drag the capstone 3 km from the quarry to the tombsite.[66]

Quarrying the stones for a tomb can take almost a month and typically involves 20-40 laborours, sometimes subcontracted by a relative. It can be months or years before the stones are actually transported to the gravesite, which is done traditionally by hand, using a wooden sled and rollers with the help of many members of the family's clan. Building the sled itself can take several days, and typically males between the ages of 10-60 are assembled to pull the stone from the quarry to the tombsite. Smaller capstones may be moved by a few hundred members of a clan, but larger ones can involve upwards of 2,000 individuals over many days. Sometimes the stones are draped with woven cloths given as gifts by relatives of the owner. The sidewalls are smaller and usually require fewer participants. The entire process is accompanied by large feasts and ritual singers provided by the owner. Some contemporary practitioners now choose to use large machinery and trucks to move the stones.

Once on site, the stones were traditionally assembled and mortared with a mix of water buffalo dung and Ash, but are now more commonly cemented together. Typically, the walls are assembled first, and then the capstone is incrementally elevated to the height of the walls by means of a wood scaffolding which is inserted log by log at alternating ends. Once the capstone is at the correct height beside the walls it is slid into place above the tomb. Alternately, some tombs are constructed by dragging the capstone up a fabricated ramp and then assembling the sidewalls below it, before removing the ramp structure to let the capstone rest upon the walls. Often, but not always, the finished structure is decorated by a professional stone carver with symbolic motifs. The carving alone can at times take over a month to complete.[67]

References in literature and fiction

And Moses wrote down all the words of the Lord. He rose early in the morning and built an altar at the foot of the mountain, and twelve pillars, according to the twelve tribes of Israel.

— The Old Testament, Book of Exodus, 24:4 (400 BC)[68]

Gallery

Menhirs at the Almendres Cromlech, Évora, Portugal

Menhirs at the Almendres Cromlech, Évora, Portugal Megalithic tomb in Khakasiya, Russian Federation

Megalithic tomb in Khakasiya, Russian Federation- Capstones of southern-style megalithic burials in Guam-ri, Jeollabuk-do, Korea

Ale's Stones at Kåseberga, around ten kilometres south east of Ystad, Sweden

Ale's Stones at Kåseberga, around ten kilometres south east of Ystad, Sweden

Deer stone near Mörön in Mongolia

Deer stone near Mörön in Mongolia the Great Menhir of Er Grah in Brittany, the largest known single stone erected by Neolithic man, which later fell down

the Great Menhir of Er Grah in Brittany, the largest known single stone erected by Neolithic man, which later fell down

- Dolmen of Avola (Sicily, Italy)

Dolmen at the Kuejiyeh dolmen field close to Madaba, Jordan

Dolmen at the Kuejiyeh dolmen field close to Madaba, Jordan Dolmen of Menga in Antequera, Spain

Dolmen of Menga in Antequera, Spain

See also

- Bilger's rocks

- British megalith architecture

- Irish megalithic tombs

- List of megalithic sites

- Megalithic monuments in Europe

- Megaliths in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

- Megaliths in the Urals

- Nature worship

- Nordic megalith architecture

- Plain of Jars ranging from the Khorat Plateau in Thailand in the south, through Laos and to Dima Hasao of northerneastern India.

- Standing stone

- Stone slab

- Straße der Megalithkultur – tourist route from Osnabrück to Oldenburg via some 33 Megalithic sites.

- Unidentified submerged object

- Yonaguni Monument

- Stone circles of Junapani

Footnotes

- Construction of large stone monuments in the rest of the classical world consisted of assembled sections of relatively small stones, including most construction in Egypt. Elsewhere in the world some megalithic construction persisted: Occasionally large stone sculptures, relief carvings, and open pillared temples were carved in-place in cliff-faces, out of natural rock.

References

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/articles/europe-megalithic-monuments-france-sea-routes-mediterranean-180971467/

- Herbert, A. Cyclops Christianus, or the supposed Antiquity of Stonehenge. London, J. Petheram, 1849.

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/magazine/2017/11-12/history-europe-megaliths-solstice/

- Johnson, W. (1908) p. 67. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- Price, T. Douglas; Feinman, Gary M. (2005). "Glossary". Images of the Past (4th Student ed.). McGraw-Hill Higher Education. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- "Glossary of Cemetery Terms". Rochester's History: An Illustrated Timeline. n.d. Definition of megalith. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- "Baalbek myth megalith". New Yorker. Annals of Technology.

- "menhir". cambridge.org.

- "monolith". cambridge.org.

- "[no title cited]". english.cha.go.kr.

- "[no title cited]". architetturadipietra.it.

- Lodolo, Emanuele; Ben-Avraham, Ben (September 2015). "A submerged monolith in the Sicilian Channel (central Mediterranean Sea): Evidence for Mesolithic human activity". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 3: 398–407. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.07.003.

- https://www.academia.edu/4986883/Some_stones_can_speak_the_social_structure_identity_and_territoriality_of_sw_atlantic_Europe_complex_appropriator_communities_reflected_in_their_standing_stones

- https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/11/science/megaliths-archaeology-tombs.html

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/132/

- https://www.visitalgarve.pt/en/3297/archaeology.aspx

- Calado, Manuel (2015). "Menhirs of Portugal:all Quiet on the Western Front?". Statues-menhirs et pierres levéesdu Néolithique à aujourd’hui. Saint-Pons-de-Thomières: Direction régionale des affaires culturelles Languedoc-RoussillonGroupe Archéologique du Saint-Ponais. pp. 243–253. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- Notroff, Jens; Dietrich, Oliver (January 2013). "Establishing a radiocarbon sequence for Göbekli Tepe. State of research and new data". NeoLithics: 36–47.

- "The Site". The Tepe Telegrams: News & Notes from the Göbekli Tepe Research Staff. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- Notroff, Jens (May 2017). "Introducing: Enclosure H – Welcoming a new member to the Göbekli Tepe-family". The Tepe Telegrams: News & Notes from the Göbekli Tepe Research Staff. Blog entry 26. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- Dietrich, Oliver (August 2016). "Emblematic signs? On the iconography of animals at Göbekli Tepe". The Tepe Telegrams: News & Notes from the Göbekli Tepe Research Staff. Blog entry 16. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- Birch, Nicholas (22 April 2008). "7,000 years older than Stonehenge: The site that stunned archaeologists". The Guardian. London, UK.

- Dietrich, Oliver (August 2016). "Who built Göbekli Tepe?". The Tepe Telegrams: News & Notes from the Göbekli Tepe Research Staff. Blog entry 18. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- Dietrich, O.; Heun, M.; Notroff, J.; Schmidt, K.; Zarnkow, M. (2012). "The role of cult and feasting in the emergence of Neolithic communities. New evidence from Göbekli Tepe, south-eastern Turkey". Antiquity. 86 (33): 674–695. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00047840.

- Dietrich, Laura; et al. (2019). "Cereal processing at early Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, southeastern Turkey". PLoS One. 14 (5): e0215214. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1415214D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0215214. PMC 6493732. PMID 31042741.

- "The World's First Temple". Archaeology magazine. Nov–Dec 2008. p. 23.

- Mithen, S. (2003). After the Ice - A global human History, 21,000-5,000 BC. London, UK. pp. 62–71.

- Scheltema, H.G. (2008). Megalithic Jordan; an introduction and field guide. Amman, Jordan: The American Center of Oriental Research.

- "Atlit-Yam, Israel". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help), from the feature by Jo Marchant (Nov 28, 2009). "Drowned cities: Myths and secrets of the deep". Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Schulz Paulsson, B. (2019-02-11). "Radiocarbon dates and Bayesian modeling support maritime diffusion model for megaliths in Europe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (9): 3460–3465. doi:10.1073/pnas.1813268116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6397522. PMID 30808740.

- Salvatore Piccolo, op. cit., pp. 14-17.

- "Louisenlund tæt ved Østermarie på Bornholm". Europage.dk (in Danish). Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- Slayman, Andrew L. (27 May 1998). "Neolithic skywatchers". Archaeology. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- Alan Hall (6 April 1998). "Ancient Alignments". Scientific American. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- J. Clendenon. "Nabta". Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- Krup, Edwin C. (2003). Echoes of the Ancient Skies. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 170–171. ISBN 0-486-42882-6.

- Goindol [Megalith] in Hanguk Gogohak Sajeon [Dictionary of Korean Archaeology], National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage (ed.) NRICH, Seoul. ISBN 89-5508-025-5 pp. 72-75.

- Rhee, Song-nai; Choi, Mong-lyong (1992). "Emergence of Complex Society in Prehistoric Korea". Journal of World Prehistory. 6 (1): 68. doi:10.1007/bf00997585.

- Rhee and Choi (1992): 70

- Nelson, Sarah M. (1999) "Megalithic Monuments and the Introduction of Rice into Korea" in The Prehistory of Food: Appetites for Change. C. Gosden and J. Hather (eds.) Routledge, London. pp.147–165

- Rhee and Choi (1992): 68

- Nelson (1999)

- GARI [Gyeongnam Archaeological Research Institute] (2002) Jinju Daepyeong Okbang 1 - 9 Jigu Mumun Sidae Jibrak [The Mumun Period Settlement at Localities 1 - 9, Okbang in Daepyeong, Jinju]. GARI, Jinju.

- Bale, Martin T. "Excavations of Large-scale Megalithic Burials at Yulha-ri, Gimhae-si, Gyeongsang Nam-do" in Early Korea Project. Korea Institute, Harvard University. Retrieved 10 October 2007

- I.G.N. Anom; Sri Sugiyanti; Hadniwati Hasibuan (1996). Maulana Ibrahim; Samidi (eds.). Hasil Pemugaran dan Temuan Benda Cagar Budaya PJP I (in Indonesian). Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan. p. 87.

- |Cipari archaeological park discloses prehistoric life in West Java.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-02-23. Retrieved 2009-12-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)|Lore Lindu National Park, Central Sulawesi.

- P, Pavan. "Megalith from 5000 BC found in Telangana". timesofindia.

- N.Vahia, M. Menon, Abbas, Yadav, Mayank, Srikumar, Riza, Nisha. "Megaliths in Ancient India and their possible association to astronomy" (PDF). tifr.res.in. Tata Institute of Fundamental Research and Faculty of Architecture, Manipal Institite of Technology.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Anuja, Geetali (2002). "Living Megalithic practices amongst the Madia gonds of Bhamragad, District Gadchiroli, Maharashtra". Puratattva. 32 (1): 244. Archived from the original on 2013-05-10. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- N.Vahia, M. Menon, Abbas, Yadav, Mayank, Srikumar, Riza, Nisha. "Megaliths in Ancient India and their possible association to astronomy" (PDF). tifr.res.in. Tata Institute of Fundamental Research and Faculty of Architecture, Manipal Institite of Technology.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- N.Vahia, M. Menon, Abbas, Yadav & p.4.

- N.Vahia, M. Menon, Abbas, Yadav & p.3-4.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India. New Delhi: Pearson Education. p. 252. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- Rao, K.P. "Megalithic Anthropomorphic Statues: Meaning and Significance". ResearchWorks Journal Hosting.

- d'Alviella, Goblet, et al. (1892) pp.22-23

- Goblet, et al. (1892) p.23

- Gaillard, Gérald (2004) The Routledge Dictionary of Anthropologists. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-22825-5, p.48

- Lancaster Brown, P. (1976) p.267

- Mackoe, Euan W, "The structure and skills of British Neolithic Society: a brief response to Clive Ruggles & Gordon Barclay. (Response)", Antiquity September 2002

- Harris, Barney (2018). "Roll Me a Great Stone: A Brief Historiography of Megalithic Construction and the Genesis of the Roller Hypothesis". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 37 (3): 267–281. doi:10.1111/ojoa.12142.

- Keane, A. H. (1896) p.124

- Lancaster (1976). Page 6. (cf., French word alignement is used to describe standing stones arranged in rows to form long ‘processional' avenues)

- https://medium.com/@suedavies_77888/the-megaliths-of-indonesia-4f4df24ff52d

- "Marapu people struggle to get their beliefs recognized". The Jjakarta Post. 17 March 2014.

- Eveleigh, Mark. "Sumba: Inside Indonesia's secretive Marapu religion". The Independent. Sumba travel / Indonesia travel. London, UK.

Sumba’s Marapu religion is possibly the most expensive to follow in the world.

- The megalithic tradition (PDF). Passage to Indonesia (Report). West Sumba.

- https://biblia.com/bible/esv/Exodus%2024:4

Articles

- A Fleming, "Megaliths and post-modernism. The case of Wales". Antiquity, 2005.

- A Fleming, "Phenomenology and the Megaliths of Wales: a Dreaming Too Far?". Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 1999

- A Sherratt, "The Genesis of Megaliths". World Archaeology. 1990. (JSTOR)

- A Thom, "Megaliths and Mathematics". Antiquity, 1966.

- Turnbull, D (2002). "Performance and Narrative, Bodies and Movement in the Construction of Places and Objects, Spaces and Knowledges: The Case of the Maltese Megaliths". Theory, Culture & Society. 19 (5–6): 125–143. doi:10.1177/026327602761899183.

- G Kubler, "Period, Style and Meaning in Ancient American Art". New Literary History, Vol. 1, No. 2, A Symposium on Periods (Winter, 1970), pp. 127–144. doi:10.2307/468624

- HJ Fleure, HJE Peake, "Megaliths and Beakers". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 60, Jan. - Jun., 1930 (Jan. - Jun., 1930), pp. 47–71. doi:10.2307/2843859

- J McKim Malville, F Wendorf, AA Mazar, R Schild, "Megaliths and Neolithic astronomy in southern Egypt". Nature, 1998.

- KL Feder, "Irrationality and Popular Archaeology". American Antiquity, Vol. 49, No. 3 (July 1984), pp. 525–541. doi:10.2307/280358

- Hiscock, P (1996). "The New Age of alternative archaeology of Australia". Archaeology in Oceania. 31 (3): 152–164. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.1996.tb00358.x. Archived from the original on 2007-06-10.

- MW Ovenden, DA Rodger, "Megaliths and Medicine Wheels". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, 1978

Books

- Asthana, S. (1976). History and archaeology of India's contacts with other countries, from earliest times to 300 B.C.. Delhi: B.R. Pub. Corp.

- Deo, S. B. (1973). Problem of South Indian megaliths. Dharwar: Kannada Research Institute, Karnatak University.

- Goblet d'Alviella, E., & Wicksteed, P. H. (1892). Lectures on the origin and growth of the conception of God as illustrated by anthropology and history. London: Williams and Norgate.

- Goudsward, D., & Stone, R. E. (2003). America's Stonehenge: the . Boston: Branden Books.

- Illustrated Encyclopedia of Humankind (The): Worlds Apart (1994) Weldon Owen Pty Limited

- Keane, A. H. (1896). Ethnology. Cambridge: University Press.

- Johnson, Walter (1908). Folk-Memory: Or, The Continuity of British Archaeology. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Lancaster Brown, P. (1976). Megaliths, myths, and men: an introduction to astro-archaeology. New York: Taplinger Pub. Co.

- Moffett, M., Fazio, M. W., & Wodehouse, L. (2004). A world history of architecture. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- Nelson, Sarah M. (1993) The Archaeology of Korea. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- O'Kelly, M. J., et al. (1989). Early Ireland: An Introduction to Irish Prehistory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-33687-2

- Parker, Joanne (editor) (2009). Written On Stone: The Cultural Reception of British Prehistoric Monuments (Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2009). ISBN 1-4438-1338-9

- Patton, Mark (1993). Statements in Stone: monuments and society in Neolithic Brittany. Routledge. 209 pages. ISBN 0-415-06729-4

- Piccolo, Salvatore (2013). Ancient Stones: The Prehistoric Dolmens of Sicily. Thornham/Norfolk: Brazen Head Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9565106-2-4

- Pohribný, Jan (photo) & Richards, J (introduction) (2007). Magic Stones; the secret world of ancient megaliths. London: Merrell. ISBN 978-1-85894-413-5

- Pozzi, Alberto (2013). Megalithism - Sacred and Pagan Architecture in Prehistory. Universal Publisher. ISBN 978-1-6123-3255-0

- Scheltema, H.G. (2008). Megalithic Jordan; an introduction and field guide. Amman, Jordan: The American Center of Oriental Research. ISBN 978-9957-8543-3-1

- Stukeley, W., Burl, A., & Mortimer, N. (2005). Stukeley's 'Stonehenge': an unpublished manuscript, 1721-1724. New Haven [Conn.]: Yale University Press.

- Subbayya, K. K. (1978). Archaeology of Coorg with special reference to megaliths. Mysore: Geetha Book House.

- Tyler, J. M. (1921). The new stone age in northern Europe. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Megalith |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Megaliths. |

- Catalog of megaliths

- MegalithicIreland.com

- Dolmens, Menhirs & Stones-Circles in the South of France

- Megaliths in Charente-Maritime, France

- Dolmen Path - Russian Megaliths

- The Megalithic Portal and Megalith Map

- Index of Megalithic monuments in Ireland

- The Modern Antiquarian

- Pretanic World - Megaliths and Monuments

- Modern Megalith-Building