Alignment (archaeology)

An alignment in archaeology is a co-linear arrangement of features or structures with external landmarks,[1] in archaeoastronomy the term may refer to an alignment with an astronomically significant point or axis.[1]

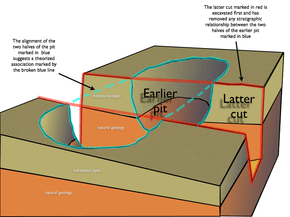

"Alignment" may also refer to circumstantial or secondary type of evidence used to infer archaeological association of archeological features, such as postholes, by virtue of their physical relationships rather than stratigraphic ones.

Types

Large scale alignments

The alignment of features on a site within or across several archaeological phases many times is an indication of a larger topology to the formation of features relating to activity in the archaeological record. Structures buildings and liner features such as ditches can all have common alignments that relate to a feature that is not exposed during excavation or is off-site. An example would be that a road has biased the alignment of features some way back from the actual road side. Another example will be contours or water courses which may be buried or obscure.

Vertical alignments

Vertical alignments may demonstrate evolution of long term land use throughout time. Examples: roads and structures built upon earlier roads or other structures.

Uses

Grave alignment is used to infer religious beliefs (e.g. Christianity).[2] The change in astronomical alignments over time may be used to infer dates of construction of structures with supposed astronomical significance, or vice versa.[3]

Potential errors

Chance alignments may mislead; the number of potential astronomical alignment targets over time is large; statistical significance can be used when examining groups of alignments.[4]

Ley lines

The landscape features known as Ley lines were discovered by Alfred Watkins in the 1920s, based on apparent co-linearity of features, who inferred an ancient system of surveying landmarks. The idea was rejected by archaeologists,[5] and the line associations have been shown to be not generally statistically significant.[6]

See also

- Stone row, also known as Stone alignment

- Paleomagnetism and archaeomagnetic dating, archaeological study of magnetic alignment

- Body positioning in Burial

- Giza Necropolis, Stonehenge, Newgrange; common examples of structure with supposed astronomical alignments

References

- Shaw, Ian; Jameson, Robert (1999), Dictionary of Archaeology, Blackwell Publishers, "Alignment", p.37, ISBN 0-631-17423-0

- Daniell, Christopher; Thompson, Victoria (1999), "Pagans and Christians: 400-1150", in Jupp, Peter C.; Gittings, Clare (eds.), Death in England: An illustrated History, Manchester University Press, p. 68, ISBN 0 7190 5470 2

- Hawkins, Gerald S. (October 1973), "Astro-Archeology - The Unwritten Evidence", Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 29 (8): 58

- Renfrew, Colin; Bahn, Paul, eds. (2005), Archaeology : the Key Concepts, Routledge, Archaeoastronomy, pp.14-15, ISBN 0-415-31757-6

- Devereux, Paul; Forrest, Robert (23–30 December 1982), "Straight lines on an ancient landscape", New Scientist: 822–826

- Sullivan, Danny (2004), Ley Lines: The Greatest Landscape Mystery, Green Magic, pp. 19–21, ISBN 0 9542 9634 6