Chatham County, Georgia

Chatham County is located in the U.S. state of Georgia, on the state's Atlantic coast. The county seat and largest city is Savannah. One of the original counties of Georgia, Chatham County was created February 5, 1777, and is named after William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham.[1]

Chatham County | |

|---|---|

Chatham County Administrative and Legislative Center in Savannah | |

Seal | |

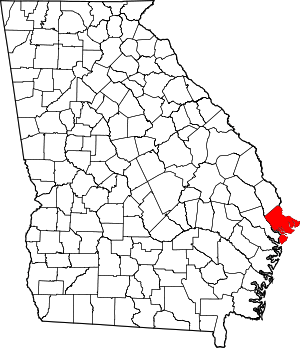

Location within the U.S. state of Georgia | |

Georgia's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 31°58′N 81°05′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | February 5, 1777 |

| Named for | William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham |

| Seat | Savannah |

| Largest city | Savannah |

| Area | |

| • Total | 632 sq mi (1,640 km2) |

| • Land | 426 sq mi (1,100 km2) |

| • Water | 206 sq mi (530 km2) 32.6%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2019) | 289,430 |

| • Density | 622/sq mi (240/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 1st |

| Website | www |

The U.S. Census Bureau's 2019 population estimate for Chatham County was 289,430 residents,[2] making Chatham the fifth most populous county in Georgia, and the most populous Georgia county outside the Atlanta metropolitan area. The official 2010 Census counted 265,128 residents in Chatham County.[3] Chatham is the core county of the Savannah metropolitan area.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 632 square miles (1,640 km2), of which 426 square miles (1,100 km2) is land and 206 square miles (530 km2) (32.6%) is water.[4]

Chatham County is the northernmost of Georgia's coastal counties on the Atlantic Ocean. It is bounded on the northeast by the Savannah River, and in the southwest bounded by the Ogeechee River.

The bulk of Chatham County, an area with a northern border in a line from Bloomingdale to Tybee Island, is located in the Ogeechee Coastal sub-basin of the Ogeechee River basin. The portion of the county north of that line is located in the Lower Savannah River sub-basin of the Savannah River basin, while the very southern fringes of the Chatham County are located in the Lower Ogeechee River sub-basin of the Ogeechee River basin.[5]

Major highways

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- State Route 26 Connector

Adjacent counties

- Jasper County, South Carolina – northeast

- Bryan County – west/southwest

- Liberty County - southeast

- Effingham County – northwest

National protected areas

- Fort Pulaski National Monument

- Savannah National Wildlife Refuge (part)

- Wassaw National Wildlife Refuge

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 10,769 | — | |

| 1800 | 12,946 | 20.2% | |

| 1810 | 13,540 | 4.6% | |

| 1820 | 14,737 | 8.8% | |

| 1830 | 14,127 | −4.1% | |

| 1840 | 18,801 | 33.1% | |

| 1850 | 23,901 | 27.1% | |

| 1860 | 31,043 | 29.9% | |

| 1870 | 41,279 | 33.0% | |

| 1880 | 45,023 | 9.1% | |

| 1890 | 57,740 | 28.2% | |

| 1900 | 71,239 | 23.4% | |

| 1910 | 79,690 | 11.9% | |

| 1920 | 100,032 | 25.5% | |

| 1930 | 105,431 | 5.4% | |

| 1940 | 117,970 | 11.9% | |

| 1950 | 151,481 | 28.4% | |

| 1960 | 188,299 | 24.3% | |

| 1970 | 187,767 | −0.3% | |

| 1980 | 202,226 | 7.7% | |

| 1990 | 216,935 | 7.3% | |

| 2000 | 232,048 | 7.0% | |

| 2010 | 265,128 | 14.3% | |

| Est. 2019 | 289,430 | [6] | 9.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[7] 1790-1960[8] 1900-1990[9] 1990-2000[10] 2010-2019[3] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 265,128 people, 103,038 households, and 64,613 families residing in the county.[11] The population density was 621.7 inhabitants per square mile (240.0/km2). There were 119,323 housing units at an average density of 279.8 per square mile (108.0/km2).[12] The racial makeup of the county was 52.8% white, 40.1% black or African American, 2.4% Asian, 0.3% American Indian, 0.1% Pacific islander, 2.2% from other races, and 2.1% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 5.4% of the population.[11] In terms of ancestry, 9.8% were Irish, 8.7% were English, 7.9% were German, and 4.6% were American.[13]

Of the 103,038 households, 31.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.0% were married couples living together, 17.5% had a female householder with no husband present, 37.3% were non-families, and 28.7% of all households were made up of individuals. The average household size was 2.45 and the average family size was 3.03. The median age was 34.0 years.[11]

The median income for a household in the county was $44,928 and the median income for a family was $54,933. Males had a median income of $42,239 versus $31,778 for females. The per capita income for the county was $25,397. About 11.6% of families and 16.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 23.4% of those under age 18 and 10.8% of those age 65 or over.[14]

Education

Public schools are operated by Savannah-Chatham County Public Schools.

Libraries

Chatham County's Live Oak Public Libraries constitute a regional library system that provides services to three Georgia counties: Chatham, Effingham, and Liberty. The former name of the system, the Chatham, Effingham and Liberty County Public Libraries, described this collaboration. In 2002, the name was changed to Live Oak, which reflects the personality of the region as well as the life and growth of its branches.[15] At the beginning of the twentieth century, city leaders in Savannah began to discuss the need for a public library. The history of libraries in Chatham County dates to 1903. According to Geraldine LeMay, former director of the Savannah Public Chatham-Effingham and Liberty Regional Library, the Georgia Historical Society and the city of Savannah worked out a plan that year to establish the Savannah Public Library.[16] The idea was the brainchild of the Georgia Historical Society, which set up a planning committee to determine how the facilities of the society might best be useful to the city of Savannah.[17] In a joint meeting of committee members from the Society and the city of Savannah, a Free Public Library was established that would prove to be of great value to the community. This Free Public Library, however, did not serve citizens of color.

The parties agreed to allow free use of the Society's books, provide physical space for the library, and annually contribute $500 in financial support for the library. In turn, the city would contribute $3,000 in annual support.[17] The library opened in June 1903 but did not fully serve the public until November. By 1909, the Georgia Historical Society was no longer able to meet its financial commitment, leaving the city to provide full financial support. The library remained at Hodgson Hall, the space provided by the Georgia Historical Society, until 1915. From its early beginnings the library offered special services to the community, including a department for children (although no one under the age of fourteen was permitted to borrow books). The physical space at Hodgson Hall became too small to accommodate a large reference department, so the library established only a small collection of reference materials. .[17] In 1916, the Savannah Public Library opened to doors to a new facility on Bull Street within the Savannah Victorian Historic District. The new facility was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation. As the library grew in popularity, it again found itself needing more space. The building was able to add additional space in 1936 thanks to a grant from the U.S. Works Progress Administration (WPA).[18] With an ever-increasing population the library's board of directors decided to expand services beyond the Main Library. In 1916, two branch libraries were opened: the East Side Branch at Habersham and Congress Streets, and the Waters Avenue Branch. The services provided by these two branches were confined to children.[17] To help further expand services, the Georgia Historical Society once again offered the library space at Hodgson Hall to be used as a branch library. This move was of mutual benefit to both the library and the Society. The library gained needed space for a downtown branch and the Society could organize and catalog materials. According to the history written by Lemay, some 5,027 volumes belonging to the Georgia Historical Society were cataloged by the library. This branch library continued operating until 1948, when it was sold to Armstrong Junior College (now Georgia Southern University-Armstrong Campus) to establish an academic library.

In 1924 a traveling book collection was instituted and placed in four public elementary schools; other schools were added when available materials and staff time allowed. In 1926, the Savannah Morning News donated space for a Downtown branch to primarily serve the business community. The Downtown branch experienced several changes in venues over the years until it was given a permanent home in the Gamble Building. The Gamble Building sits on Factors' Walk, on Bay Street next to Savannah's City Hall. With this move, the branch was renamed in honor of Ola Wyeth, the former president of the Georgia Library Association (1925).

In 1940 a bookmobile service was started to provide outreach to rural communities around Savannah.[15] The Effingham County Library joined the Savannah Public Library in 1945 to form the Chatham–Effingham County Regional Library.[15] In 1956, the library system was expanded to include Liberty County, resulting in the Chatham–Effingham–Liberty Regional Library (CEL).[15]

When the United States Supreme Court declared de jure segregation illegal and unconstitutional, the library system experienced one of its greatest changes. As a result of this ruling, the "Library for the Colored Citizens of Savannah" was brought under the auspices of the Chatham-Effingham-Liberty Regional Library System (1963). This move made the library system a truly "free public library" serving all the citizens of Chatham, Effingham, and Liberty counties.

Government and infrastructure

The Coastal State Prison, a Georgia Department of Corrections state prison, is located in Savannah, near Garden City.[19][20]

Chatham County is primarily policed by the Chatham County Police Department (CCPD) and the Georgia State Patrol. The Chatham County Sheriff's Office is the enforcement arm of the county court system and operates the county jail.[21] The SCMPD was formed on January 1, 2005 when the separate Savannah Police Department and Chatham County Police merged.[22]

Communities

Municipalities

Towns

Census-designated places (unincorporated)

Other unincorporated communities

Politics

Chatham County was a swing county for the latter half of the 20th century, being one of the earliest Georgia counties to convert from a Solid South voting pattern. From 2008 onward, it has tended to vote much more for the Democratic Party than the state as a whole in presidential elections as a primarily urban county with a large African American population, especially in its principal city of Savannah.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 40.4% 45,688 | 55.1% 62,290 | 4.5% 5,073 |

| 2012 | 43.4% 47,204 | 55.4% 60,246 | 1.3% 1,371 |

| 2008 | 42.4% 46,829 | 56.8% 62,755 | 0.8% 858 |

| 2004 | 49.6% 45,484 | 49.8% 45,630 | 0.6% 557 |

| 2000 | 49.5% 37,847 | 49.2% 37,590 | 1.4% 1,038 |

| 1996 | 44.9% 31,987 | 50.2% 35,781 | 4.9% 3,509 |

| 1992 | 44.3% 31,925 | 43.8% 31,533 | 11.9% 8,611 |

| 1988 | 58.1% 35,623 | 40.9% 25,063 | 1.0% 603 |

| 1984 | 57.7% 38,482 | 42.4% 28,271 | |

| 1980 | 46.7% 26,499 | 50.0% 28,413 | 3.3% 1,869 |

| 1976 | 43.0% 24,160 | 57.0% 32,075 | |

| 1972 | 71.0% 38,079 | 29.0% 15,566 | |

| 1968 | 33.8% 18,106 | 34.0% 18,201 | 32.2% 17,238 |

| 1964 | 58.9% 33,141 | 41.2% 23,176 | 0.0% 1 |

| 1960 | 52.5% 17,935 | 47.5% 16,240 | |

| 1956 | 62.5% 14,520 | 37.5% 8,698 | |

| 1952 | 51.9% 15,532 | 48.1% 14,370 | |

| 1948 | 25.9% 6,194 | 45.5% 10,864 | 28.6% 6,839 |

| 1944 | 19.1% 2,058 | 80.9% 8,725 | |

| 1940 | 16.5% 1,985 | 83.4% 10,048 | 0.2% 19 |

| 1936 | 10.9% 1,227 | 88.9% 10,019 | 0.2% 24 |

| 1932 | 17.1% 1,669 | 82.3% 8,020 | 0.6% 55 |

| 1928 | 48.9% 5,288 | 51.1% 5,534 | |

| 1924 | 20.4% 1,800 | 69.9% 6,158 | 9.7% 857 |

| 1920 | 19.0% 995 | 81.0% 4,243 | |

| 1916 | 12.9% 616 | 79.4% 3,797 | 7.7% 368 |

| 1912 | 7.5% 332 | 87.1% 3,864 | 5.4% 238 |

See also

- Georgia Senate, District 2

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Chatham County, Georgia

References

- Krakow, Kenneth K. (1975). Georgia Place-Names: Their History and Origins (PDF). Macon, GA: Winship Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-915430-00-2.

- "County Population Estimates 2019 US Census".

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Georgia Soil and Water Conservation Commission Interactive Mapping Experience". Georgia Soil and Water Conservation Commission. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- "DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- "Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- "DP02 SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- "DP03 SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- "Library History". Live Oak Public Libraries. Live Oak Public Libraries. Archived from the original on April 10, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- LeMay, Geraldine. "HISTORY OF THE SAVANNAH PUBLIC CHATHAM – EFFINGHAM – LIBERTY REGIONAL AND CARNEGIE LIBRARIES 1903 – 1963" (PDF). Live Oak Public Libraries. Live Oak Public Libraries. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- LeMay, Geraldine. "History of the Savannah Public Chathm-Effingham-Liberty Regional and Carnegie Libraries 1903-163" (PDF). Live Oak Public Libraries (LOPL). LOPL. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2017. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- LeMay, Geraldine. "History of the Savannah Public Chatham-Effingham-Liberty Regional and Carnegie Libraries 1903-163" (PDF). Live Oak Public Libraries (LOPL). LOPL. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2017. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- "City of Savannah Neighborhoods 2008 Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." City of Savannah. Retrieved on September 15, 2010.

- "Coastal State Prison Archived 2010-09-04 at the Wayback Machine." Georgia Department of Corrections. Retrieved on September 15, 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 27, 2010. Retrieved August 31, 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 30, 2010. Retrieved August 31, 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 19, 2018.