CSX Transportation

CSX Transportation (reporting mark CSXT) is a Class I freight railroad operating in the eastern United States and the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec. The railroad operates approximately 21,000 route miles (34,000 km) of track.[1] The company operates as a subsidiary of CSX Corporation, a Fortune 500 company headquartered in Jacksonville, Florida.[2][3]

| |

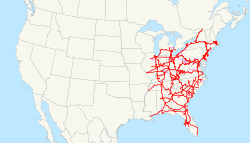

CSX system map (trackage rights in purple) | |

.jpg) CSX 660, a GE AC6000CW, westbound at Point of Rocks, Maryland | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Jacksonville, Florida |

| Reporting mark | CSXT |

| Locale | |

| Dates of operation | July 1, 1986–present |

| Predecessor | |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 21,000 miles (34,000 km) |

| Other | |

| Website | csx |

History

Early years

CSX Corporation was formed on November 1, 1980, by combining the railroads of the former Chessie System with Seaboard Coast Line Industries.[4]

The name came about during merger talks between Chessie System and SCL, commonly called "Chessie" and "Seaboard". The company chairmen said it was important for the new name to include neither of those names because it was a partnership. Employees were asked for suggestions, most of which consisted of combinations of the initials. At the same time a temporary shorthand name was needed for discussions with the Interstate Commerce Commission. "CSC" was chosen but belonged to a trucking company in Virginia. "CSM" (for "Chessie-Seaboard Merger") was also taken. The lawyers decided to use "CSX", and the name stuck. In the public announcement, it was said that "CSX is singularly appropriate. C can stand for Chessie, S for Seaboard, and X, which actually has no meaning." However, an August 9, 2016, article on the Railway Age website stated that " ... the 'X' was for 'Consolidated' ".[5] The T had to be added to CSX when used as a reporting mark because reporting marks that end in X means that the car is owned by a leasing company or private car owner. The company introduced its current slogan, "How Tomorrow Moves", in 2008.[6]

The originator of SCL was the former Seaboard Air Line Railroad, which previously merged with the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad in 1967 to form the Seaboard Coast Line. In later years, it merged with the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, as well as several smaller subsidiaries such as the Clinchfield Railroad, Atlanta & West Point Railroad, Monon Railroad and the Georgia Railroad. From the late 1970s onward these railroads were known collectively as the Family Lines. In 1982, they were merged into a single railroad, the Seaboard System Railroad.[4]

The origin of the Chessie System was the former Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, which had merged with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and the Western Maryland Railway.[4]

Despite the merger in 1980, CSX Transportation never had its own identity (meaning no CSX painted locomotives or rolling stock) as a common carrier railroad until 1986. In that year, Seaboard System changed its name to CSX Transportation. On April 30, 1987, the B&O merged into the C&O. With the Western Maryland having already merged into the C&O, this left the C&O as the sole operating railroad under the Chessie System banner. Finally, on August 31, 1987, C&O/Chessie System merged into CSX Transportation, bringing all of the major CSX railroads under one banner.

Conrail acquisition

On June 23, 1997, CSX and Norfolk Southern Railway (NS) filed a joint application with the Surface Transportation Board for authority to purchase, divide, and operate the assets of the 11,000-mile (18,000 km) Conrail, which had been created in 1976 by bringing together several ailing Northeastern railway systems into a government-owned corporation. On June 6, 1998, the STB approved the CSX–NS application and set August 22, 1998, as the effective date of its decision. CSX acquired 42 percent of Conrail's assets, and NS received the remaining 58 percent. As a result of the transaction, CSX's rail operations grew to include some 3,800 miles (6,100 km) of the Conrail system (predominantly lines that had belonged to the former New York Central Railroad). CSX began operating its trains on its portion of the Conrail network on June 1, 1999. CSX now serves much of the Eastern United States, with a few routes into nearby Canadian cities.

Into the 21st century

In 2014, Canadian Pacific Railway approached CSX with an offer to merge the two companies, but CSX declined, and in 2015 Canadian Pacific made an attempt to purchase and merge with Norfolk Southern,[7] but NS declined to do so as well.

In 2017, CSX announced Hunter Harrison would become its new chief executive officer; a settlement with activist investor Paul Hilal and Mantle Ridge.[8] CSX added five new directors to their board, including Harrison and Mantle Ridge founder Paul Hilal. Mantle Ridge owns 4.9% of CSX.[9] Harrison quickly moved to convert CSX rail operations to precision railroading.[10] On December 14, 2017, CSX announced that Hunter Harrison was on medical leave. Two days after the announcement, Harrison died, one day after being hospitalized for complications of an ongoing illness. CSX initially saw a 10% drop in its stock price, but turned around to hit a new 52-week high less than a month later (January 2018).[11] Harrison's successors have continued the shift to precision railroading, with most hump yards converted to flat yards, low volume shipping lanes eliminated and reductions in rolling stock and work force.

CSX also operates numerous trains to and from Oak Island Yard in Newark, New Jersey, which is operated by Conrail Shared Assets Operations (CRCX) on its and Norfolk Southern's behalf. CSX operates two pairs of daily trains to/from Oak Island, Q433 and Q434 coming from and going to Selkirk, along with Q300 and Q301 to and from South Philadelphia.

Unit trains

.jpg)

CSX operated the Juice Train which consisted of Tropicana cars that carry fresh orange juice between Bradenton, Florida, and the Greenville section of Jersey City, New Jersey. The train also runs from Bradenton to Fort Pierce, Florida, via the Florida East Coast Railway. In the 21st century, the Juice Train has been studied as a model of efficient rail transportation that can compete with trucks and other modes in the perishable-goods trade.[12] All Tropicana trains are now added to other Trains such as Q442 and Q032.

Coke Express trains run between Pittsburgh and Chicago, and other places in the Rust Belt, carrying coke to industries, mainly steel mills.

CSX also runs daily trash trains Q702 and Q703 from The Bronx to Philadelphia (via Selkirk Yard) and then Petersburg, Virginia, where they interchange with NS. These trains consist of 89-foot (27 m) flatcars loaded with four containers of trash. Another pair of trains, Q634 and Q635, operate between Selkirk, New York, and Columbus, Ohio.

Another style of unit train is a local trash train, D765, that runs between the Maryland towns of Derwood and Dickerson. The train runs daily except on Sundays; on holidays it sometimes runs twice a day. Trash is carried from Montgomery County's Shady Grove Transfer Station to a waste-to-energy plant located off the PEPCO lead to Mirant's Dickerson Generating Station. The trip is roughly 17 miles (27 km), and the train is made up of National Steel Car Company-built well cars, hauling 40-foot (12 m) containers. The first NEMX equipment was built when the D765 first started operations in 1995. In recent years, the fleet has been somewhat upgraded, repainted, and new cars have been constructed. In the early days, the locomotives powering the train were a GP40-2/RDMT slug set, but currently the train can be upwards of 47 cars. The locomotives that now routinely power the train are a pair of GE AC4400CWs, though GEVOs may also be used.

Up until May 2019, working with Union Pacific, CSX ran an extended haul perishables train, Q090. Known by railfans as the "Salad Shooter", the train ran from Wallula, Washington, to Schenectady, New York. On the return trip, the train was labeled Q091. CSX modified its Train Handling rule book to allow this train to use more power axles. In May 2019, the train was abolished.[13]

Locomotives

Paint and aesthetics

.jpg)

The first official paint scheme under the CSX name was a simple gray paint scheme with blue "CSX Transportation" lettering. Only 11 units were ever painted into this scheme.

The "Blue Down" paint scheme was introduced about a year after the aforementioned paint scheme in 1987. It is composed with an all-gray body, with a blue underframe and top of the long hood. Blue masked the top of the cab around the windshield.

In October 1988, the "Stealth" scheme was created. It is very similar to Blue Down, but the blue on the top portion of the locomotives was removed.

In 1990, the "YN2", or "Bright Future" paint scheme was introduced. The design features a yellow nose, a blue cab, and a gray hood with a blue strip along the bottom extending from the back of the cab. The yellow and blue sections have a 60 degree section slanting down toward the back of the locomotive.

In 2002, CSXT No. 8503, an EMD SD50 (that has since been downgraded to an SD50-2), was painted in the new yellow and blue YN3 scheme. More than 1,000 CSX locomotives have since been painted in the YN3 scheme.[14]

CSX recently created a new paint scheme, known as YN3b, which updates YN3 with the most recent CSX logo. The first unit to wear this scheme was ES44AH 950. Currently, CSX's ES44AHs 950-999 and 3000–3249 and the ET44AHs 3250-3474 wear the scheme, along with recently repainted older locomotives, the first of which was SD70AC CSXT 4719, which was repainted at the Huntington Locomotive Shops in September 2012. YN3b is also commonly found on the SD40-3 rebuilds.

All of the former-Conrail locomotives in active service have been repainted in a CSX livery.

In the mid-1990s, CSXT began placing a lightning bolt decal below the road number on locomotives with AC traction and still continues this practice with the new GE ES44AH and ET44AH locomotives.

CSX also has several locomotives with "spirit" stickers with a name of an important person or location in the CSX system.

In 2016, CSX placed the logos of several predecessor railroads on some locomotives, in order to maintain legal control of the logos.

On April 30, 2019, CSX unveiled locomotives 911 and 1776, two locomotives created to honor the first responders and veterans.[15] Another special unit, CSX 3194, was unveiled on August 22, 2019, in honor of the law enforcement.[16]

Locomotives

In 2015, CSX traded its 12 EMD SD80MACs for 12 SD40-2s from Norfolk Southern. They have all since been rebuilt as SD40-3s.

CSX has been significant in rebuilding locomotives. CSX has 3 rebuilds of its 4 axle EMD Locomotives. The EMD GP38-2, GP40-2, and SD40-2 have all been rebuilt to then Dash 3 standards with updated Wabtec Electronically Controlled Air Brakes, Electronic bells (E-Bell), electronic handbrakes with a mechanical backup, an airstarter on the motor with an electric start backup, a new designed crash safe cab, a new electronic control stand, YN3B paint job, and Positive Train Control (PTC) computers. They became EMD GP38-3s, GP40-3s, and SD40-3s respectively. Most are also Positive Stop Protection ( PSP ) equipped Remote Controlled Locomotives (RCL) and have amber strobe lights on each side of the cab, a Cattron Locomotive Control Unit computer, an Air Brake Transfer Valve ( that transfers brake control from manual to computer control), a speed transponder scanner on each end, and a GPS Receiver on the cab roof to pinpoint the engines location. The Dash 3 RCL can also have its handbrake applied by a Remote Control Operator (RCO) by holding the left and right Vigilance switches on the Operator Control Unit (OCU) remote box. CSX has rebuilt EMD GP35 and GP30 units as road slugs. CSX has also downgraded SD50 and GP40-2 units in order to decrease the wear and tear on the engines the EMD GP40-2s that were downgraded from 3,000 horsepower to 2,000 horsepower during this process are known as GP38-2S locomotives and CSXT 6044 is one of those that was derated. Among its EMD rebuilds, CSX has done rebuilding on many GE locomotives as well. CSX has re-powered most of its GE CW60AC and CW60AH locomotives with a GEVO-16 engine rated at 4,600 hp (3,430 kW), essentially making them an over-engined ES44AH called a CW46AH by CSX. Former Conrail GE B40-8 units have also been downgraded to 2,000 hp (1,491 kW) in an attempt to decrease wheel slip and low speeds. They were redesignated as B20-8s and CSX has since sold or stored most of these units including the 6 axle GE C40-8s. Another group of projects are the "heavy" units. CSX has modified some GE CW44AC and CW44AH units to heavy units by adding extra counterweights to the frame and in the nose of the unit shell and new computers to increase tractive effort at low speeds, they are 432,000 pounds.

CSX has also obtained a few EMD F40PHs that were retired from Amtrak for executive office car service and geometry trains. Another locomotive, an ex-MARC GP40WH-2, was acquired for the same purpose.

With the arrival of Hunter Harrison, CSX has begun to store many locomotives. By the end of 2017, CSX plans to store or retire all of the GE CW40-8, CW40-9, CW60AC, CW60AH, CW46AH, EMD SD50, SD50-2, SD50-3, SD60, SD60M, SD60I, SD70M, SD70AC, and SD70AE (SD70ACe) units. Most of the GE C40-8, B40-8, and B20-8 units stored in Corbin, Kentucky, have already been retired and sold off. Even with the passing of Harrison, his replacement, James Foote, confirmed the locomotives would still be retired.[17]

CSX ordered ten SD70ACe-T4s in August 2018, which were delivered in July the following year. They are classified as ST70AHs. CSX also has a contract with Wabtec for modernizing their fleet of CW44s. The modernized locomotives, nearly thirty in number as of June 2020, are being classified as CM44s.

Safety

Because of Ross Rowland running C&O 614 above the speed limits, in 1995, CSX started a new liability insurance requirement of $200 million to introduce their official policy, "no steam on its own wheels", banning the operation of steam locomotives and other antique rail equipment on their trackage due to safety concerns, and increased risk.[18][19]

List of accidents and incidents

- 1986 Miamisburg, Ohio, train derailment

- 1993 Big Bayou Canot train wreck

- 1996 Maryland train collision

- 2001 CSX 8888 incident, 1 minor injury. This was the inspiration for the 2010 action film Unstoppable

- 2001 Howard Street Tunnel fire

- 2007 Brooks derailment

- 2008 Welded Rail Train Derailment, GA. Involved units were CSXT #6473, CSXT #2243, CSXT #7847

- 2012 Ellicott City, Maryland, train derailment, two killed

- 2013 Spuyten Duyvil derailment

- 2014 Lynchburg, Virginia, oil train car derailment, no injuries

- 2015 Mount Carbon train derailment

- 2015 Tennessee train derailment

- 2016 "Chessie Sticker loco" CSX 366 fire in the J&L tunnel, Pittsburgh, PA[20]

- 2017 Biloxi collision with tour bus stuck on tracks, 4 killed 44 injured[21]

- 2017 Newburgh, New York, train derailment, 2 minor injuries (Q409)

- 2017 Hardin County train derailment, 23 cars derailed, no injuries

- 2017 Crawford County train derailment, 21 cars derailed, no injuries[22]

- 2017 Pittsburgh suburb coal cars derailment[23]

- 2017 Hyndman derailment, chemical release and fire[24]

- 2017 Atlanta derailment destroys occupied home[25]

- 2017 Polk County, Florida, derailment spilling molten sulfur, no injuries (Q453-26)

- 2017 Taunton, Massachusetts, derailment rail hits fuel tank, spilling everywhere

- 2017 Union, New Jersey, derailment, no injuries (Q404)

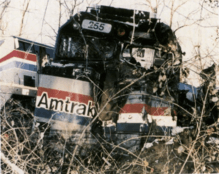

- 2018 Cayce, South Carolina, train collision involving Amtrak Silver Star and a CSX autorack train (Q210-03). 2 dead, 116 injured.

- 2018 Alexandria, Virginia – May 19, 2018. Train derails in Alexandria, falling onto Norfolk Southern tracks that cross underneath it.

- 2018 Worcester, Massachusetts – July 21, 2018. CSX Intermodal train from Worcester, Massachusetts, hits a low overpass, causing 12 cars to derail. One car nearly crashed into a car full of toxic chemicals, engineer injured.[26]

- 2018 Princeton, Indiana, derailment - track buckles and 23 cars crashed

Railyards

Hump yards

In hump yards, trains are slowly pushed over a small hill as cars are uncoupled at the crest of the hill and allowed to roll down the hump into the appropriate tracks for outbound trains.

- Avon, Indiana – Avon Yard

- Cincinnati, Ohio – Queensgate Yard

- Nashville, Tennessee – Radnor Yard

- Selkirk, New York – Selkirk Yard

- Waycross, Georgia – Rice Yard

Flat yards

In flat yards, a locomotive pulls and pushes cars to assemble a train.

- Willard, Ohio – Willard Yard (Both East and West classification humps closed)

- Birmingham, Alabama – Boyles Yard (classification hump closed)

- Buffalo, New York – Frontier Yard (classification hump removed in 2019)

- Cumberland, Maryland – Cumberland West Hump (classification hump closed)

- Hamlet, North Carolina – Hamlet Yard (classification hump closed)

- Louisville, Kentucky – Osborn Yard (for Prime Osborn, former CSX president) (classification hump closed)

- Walbridge, Ohio – Stanley Yard (classification hump closed)

- Apex, North Carolina- Apex rail yard (formerly a Seaboard yard)

- Baltimore, Maryland – Curtis Bay Yard, Seawall Yard, Davidson Yard, Locust Point Yard, Bayview Yard, Penn-Mary Yard, Mt. Clare "A" Yard, Mt. Winans Yard, Grays Yard

- Hagerstown, Maryland – Hagerstown Terminal

- Riverdale, Illinois – Barr Yard

- Dearborn, Michigan – Rougemere Yard

- Flint, Michigan – McGrew Yard

- Grand Blanc, Michigan – Grand Blanc Yard

- Grand Ledge, Michigan – Grand Ledge Yard

- Grand Rapids, Michigan – Wyoming Yard

- Holland, Michigan – Waverly Yard

- Lansing, Michigan – Ensel Yard

- Plymouth, Michigan – Plymouth Yard

- St. Clair, Michigan – St. Clair Yard

- Wixom, Michigan – Wixom Yard

- Garrett, Indiana – Garrett Yard

- Evansville, Indiana – Howell Yard

- Russell, Kentucky – Russell Yard

- Loyall, Kentucky – Loyall Yard

- Hopkinsville, Kentucky – Casky Yard

- Bronx, New York – Oak Point Yard

- Watertown, New York – Massey Yard

- East Syracuse, New York – DeWitt Yard

- Rochester, New York – Goodman Street Yard

- Niagara Falls, New York – Niagara Yard

- North Bergen, New Jersey – North Bergen Yard

- North Haven, Connecticut – Cedar Hill Yard

- Framingham, Massachusetts – Nevins Yard

- Wilmington, Delaware – Wilsmere Yard

- Richmond, Virginia – Acca Yard and Fulton Yard

- Clifton Forge, Virginia – Clifton Forge Terminal

- Charlotte, North Carolina – Pinoca Yard

- Charleston, South Carolina – Bennett Yard

- Chattanooga, Tennessee – Cravens Yard

- Greenwood, South Carolina – Maxwell Yard

- Columbia, South Carolina – Cayce Yard

- Savannah, Georgia – Southover Yard

- Columbus, Ohio – Parsons Yard

- Dayton, Ohio – Needmore Yard

- New Miami, Ohio – New River Yard

- North Excello, Ohio – Lind Yard

- Toledo, Ohio – Walbridge Yard

- Akron, Ohio – Akron "Hill" Yard

- Lordstown, Ohio – Goodman Yard (Lordstown)

- Cleveland, Ohio – Collinwood Yard and Clark Ave. Yard

- Connellsville, Pennsylvania – Connellsvillle Yard

- New Castle, Pennsylvania – New Castle Yard

- Langhorne, Pennsylvania – Woodbourne Yard

- Baldwin, Florida – Baldwin Yard

- Jacksonville, Florida – Moncrief Yard, Duval Yard, Busch Yard, Export Yard

- Tampa, Florida – Yeoman Yard, Rockport Yard

- Lakeland, Florida – Winston Yard (closed but now reopened)

- Mulberry, Florida – Mulberry Yard

- Orlando, Florida – Taft Yard

- Wildwood, Florida – Wildwood Yard

- Hialeah, Florida – Hialeah Yard (owned by State of Florida and shared with Tri-Rail and Amtrak)

- Washington, DC – Benning Yard

- Kearny, New Jersey – South Kearny Yard

- Croton, New York – Croton West Yard

- Rocky Mount, North Carolina – Rocky Mount Yard

- Danville, Illinois – Brewer Yard

- East St. Louis, Illinois – Roselake Yard

- Spartanburg, South Carolina – Spartanburg Yard

- Atlanta, Georgia – Howells Yard

- Fitzgerald, Georgia – Fitzgerald Yard (now closed)

Intermodal terminals

This is a complete list of all intermodal terminals operated by CSX Intermodal Terminals, Inc:[27]

- Atlanta, Georgia – Hulsey Yard (Closed May, 2019)[28]

- Baltimore, Maryland – Port of Baltimore

- Bedford Park, Illinois – Bedford Park Yard (Chicago)

- Blasdell, New York – Seneca Yard (Buffalo)

- Chambersburg, Pennsylvania (Harrisburg)

- Charleston, South Carolina

- Charlotte, North Carolina

- Chicago, Illinois – 59th Street Yard

- Cincinnati, Ohio[29]

- Cleveland, Ohio[30]

- Detroit, Michigan

- East St. Louis – Rose Lake Yard

- Fairburn, Georgia – Fairburn Terminal

- Hilliard, Ohio – Buckeye Yard/Columbus Van Yard[31][32]

- Indianapolis, Indiana

- Jacksonville, Florida

- Kansas City, Missouri

- Kearny, New Jersey

- Little Ferry, New Jersey

- Louisville, Kentucky – Louisville (Osborn)

- Memphis, Tennessee

- Nashville, Tennessee – Nashville (Radnor)

- North Baltimore, Ohio – Northwest Ohio Intermodal Container Transfer Facility

- North Bergen, New Jersey

- Orlando, Florida – Central Florida

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania – McKee Rocks[33]

- Portsmouth, Virginia

- Salaberry-de-Valleyfield, Quebec, Canada – Valleyfield Terminal

- Savannah, Georgia

- Springfield, Massachusetts

- St. Louis, Missouri

- Syracuse, New York – De Witt Yard

- Tampa, Florida

- Winter Haven, Florida – Central Florida ILC (Orlando)

- Worcester, Massachusetts – Worcester Terminal

Gallery

CSX SD40-2 8449, seen in Senatobia, Mississippi, on former IC rails pulling an auto train with the "dark future" paint scheme

CSX SD40-2 8449, seen in Senatobia, Mississippi, on former IC rails pulling an auto train with the "dark future" paint scheme A newer GE ES44DC in the CSX scheme crosses a diamond in Marion, Ohio

A newer GE ES44DC in the CSX scheme crosses a diamond in Marion, Ohio GEVO leads a Pan Am Railways mixed freight train in Andover, Massachusetts

GEVO leads a Pan Am Railways mixed freight train in Andover, Massachusetts CSX train led by two GE AC6000CW locomotives

CSX train led by two GE AC6000CW locomotives CSX rail tunnel at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, in the Baltimore Division

CSX rail tunnel at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, in the Baltimore Division CSX train tracks in Clearwater, Florida, in the Jacksonville Division

CSX train tracks in Clearwater, Florida, in the Jacksonville Division An AC6000CW leads a coal train through the New River Gorge in West Virginia.

An AC6000CW leads a coal train through the New River Gorge in West Virginia. A former Seaboard System B36-7 converted into an RCPHG4, which serves as a remotely controlled unit.

A former Seaboard System B36-7 converted into an RCPHG4, which serves as a remotely controlled unit. A CSX C40-8 in the YN2 "Bright Future" color scheme rests inside a railroad yard in Florida.

A CSX C40-8 in the YN2 "Bright Future" color scheme rests inside a railroad yard in Florida. CSX locomotives 2002 and 6523 pulling a local freight through DeLand, Florida.

CSX locomotives 2002 and 6523 pulling a local freight through DeLand, Florida.

See also

References

- CSX Transportation, Jacksonville, FL. "Company Overview." Archived 2011-01-29 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2012-12-02.

- "CSX Corporate Structure". Retrieved 2019-01-07.

- "Fortune 500 - CSX". Fortune. Retrieved 2019-01-07.

- "CSX merger family tree". Trains. June 2, 2006. Archived from the original on July 6, 2018. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- Vantuono, William (2016-09-28). "So what does the "X" in "CSX" really mean?". Railway Age.

- Dolinger, Milt (2006-05-01). "How CSX got its name". Trains.

- Mattioli, Dana; Hoffman, Liz; George-Cosh, David (October 13, 2014). "Canadian Pacific Approached CSX About Merger Deal". The Wall Street Journal.

- Orol, Ronald (March 6, 2017). "CSX, Mantle Ridge Reach Blockbuster Deal". TheStreet.com.

- Michael Flaherty and Aishwarya Venugopal (March 6, 2017). "UPDATE 2-CSX names Hunter Harrison CEO". Reuters.

- Barrow, Keith (September 17, 2019). "Precision Scheduled Railroading Evolution-Revolution". International Railway Journal.

- "CSX Investors Seek Clarity After CEO Death, Stock Stabilizes". Reuters. 18 December 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- "The Juice Train". Virginia Railway Express. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- Air Brake and Train Handling Rules. CSX Transportation. October 2007. pp. Section 4, Page 1.

- "Image: 8503CSX-yn3.jpg, (640 × 480 px)". trainweb.org. Retrieved 2015-09-01.

- Anderson, Chris (April 30, 2019). "CSX releases veterans, first responders commemorative units". Trains. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- https://trn.trains.com/news/news-wire/2019/08/22-csx-unveils-spirit-of-our-law-enforcement-commemorative-locomotive-no-3194

- Stephens, Bill (January 17, 2018). "'There is no turning back'". Trains. Archived from the original on January 20, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- Wrinn, Jim (2000). Steam's Camelot: Southern and Norfolk Southern Excursions in Color (1st ed.). TLC Publishing. p. 102. ISBN 1-883089-56-5.

- Spradlin, Kevin (June 24, 2010). "CSX disputes claims it pulled support for Petersburg festival in '11th hour'". Cumberland Times-News. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- https://akronrrclub.wordpress.com/2016/03/08/csx-loco-catches-fire-in-pittsburgh-no-injuries/

- Lee, Anita (15 March 2017). "Driver was 'Sober' Before Train Hit Tour Bus, Biloxi Chief Says". Sun Herald. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "Train derails near Crestline - Crawford County NowCrawford County Now". crawfordcountynow.com.

- https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/pennsylvania/articles/2017-09-28/csx-working-to-remove-25-coal-cars-derailed-in-pennsylvania

- https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Pages/DCA17FR011-prelim-report.aspx

- "Train crashes into Atlanta house, destroying it".

- Moulton, Cyrus (21 July 2018). "CSX Cars Derail at Cambridge Street Bridge in Worcester". Telegram.com. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Intermodal Terminal List". CSX. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- https://www.ajc.com/news/local-govt--politics/dreams-redevelopment-csx-closes-atlanta-hulsey-yard/QDldMvzBgGse1dyNLXRhiI/amp.html

- "Cincinnati, OH". CSX. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- "Cleveland, OH". CSX. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- "Columbus, OH". CSX.com. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- "CSX Columbus, OH". Mid-America Freight Coalition. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- Gough, Paul (11 September 2017). "Intermodal facility opens in McKees Rocks". The Pittsburgh Business Times. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

Bibliography

- Solomon, Brian (2005). CSX. Saint Paul, MN: MBI Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-7603-1796-9. OCLC 57641636.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to CSX Transportation. |

- CSX official website

- CSX History

- CSX scanner frequencies

- CSX Dispatcher code cross-reference table

- New intermodal facility in Quebec