Métis

The Métis (English: /meɪˈtiː(s)/; French: [metis]) are a multiancestral indigenous group whose homeland is in Canada and parts of the United States between the Great Lakes region and the Rocky Mountains. The Métis trace their descent to both Indigenous North Americans and European settlers. Not all people of mixed Indigenous and Settler descent are Métis, as the Métis is a distinct group of people with a distinct culture and language. Since the late 20th century, the Métis in Canada have been recognized as a distinct Indigenous peoples under the Constitution Act of 1982 and have a population of 587,545 as of 2016.[1] Smaller communities self-identifying as Métis exist in the United States,[3] such as the Little Shell Tribe of Montana. The Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians are recognized as Indian. There is debate even within the Little Shell as to whether the Metis should even be allowed to enroll. While there is much history and territory shared between the Ojibwe and Montana's Metis, Metis in the United States remain unrecognized. The Métis ethnogenesis began in the fur trade and they have been an important group in the history of Canada, as well as the foundation of the province of Manitoba.[4] The Métis have homelands and communities in the U.S., as well as in Canada, that have been separated by the drawing of the U.S.-Canada border at the 49th parallel North. Alberta is the only province in Canada with a recognized Métis land base, the eight Metis Settlements, with a population of approximately 5,000 people on 1.25 million acres.[5]

Métis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| 587,545[1] (2016[2], census) | |

| Canada | 587,545[1] |

| United States | Unknown |

| Languages | |

| Michif, Nêhiyawêwin, Canadian French, Acadian French, North American English, Hand Talk, other indigenous languages | |

| Indigenous peoples in Canada |

|---|

|

|

History

|

|

Politics

|

|

Culture

|

|

Demographics

|

|

Religions |

|

Index

|

|

Wikiprojects Portals

WikiProject

First Nations Inuit Métis |

Etymology

"Métis" is the French term for "mixed-blood". The word is a cognate of the Spanish word mestizo and the Portuguese word mestiço. Michif ([mɪˈtʃɪf]) is the name of creole language spoken by the Métis people of Western Canada and adjacent areas of the United States, mostly a mix of Cree and Canadian French.

The word derives from the French adjective métis, also spelled metice, referring to a hybrid, or someone of mixed ancestry.[6][7]:1080 In the 16th century, French colonists used the term métis as a noun for people of mixed European and indigenous American parentage in New France (now Quebec). At the time, it applied generally to French-speaking people who were of partial ethnic French descent.[6][8] It later came to be used for people of mixed European and Indigenous backgrounds in other French colonies, including Guadeloupe in the Caribbean;[9] Senegal in West Africa;[10] Algeria in North Africa;[11] and the former French Indochina in Southeast Asia.[12] The spelling Métis with an uppercase M refers to the distinct Indigenous peoples in Canada and the U.S., while the spelling métis with a lowercase m refers to the adjective. There are many different spellings of the word Métis that have been used interchangeably, including métif, michif, currently the most agreed upon spelling is Métis, however some prefer to use Metis to be inclusive to persons of both English and French descent.[13] The definition of the word is often disputed, as governments and political organizations have been the parties to define the perception of Métis in legislation, rather than Métis defining the title themselves.

The Métis people in Canada and the Métis people in the United States adopted parts of their Indigenous and European cultures while creating customs and tradition of their own, as well as developing a common language.[14] Some argue that the ethnogenesis of the Métis began when the Métis organized politically at the Battle of Seven Oaks, while others argue that the ethnogenesis began prior to this politicized battle, before the Métis emigrated from the Great Lakes region to the Western plains.[15]

Louis Riel's Writings

Métis political leader Louis Riel wrote extensively. In The Métis, Louis Riel's Last Memoir: The Métis of the North-West, Riel wrote:

The French word Métis is derived from the Latin participle mixtus, which means "mixed"; it expresses well the idea it represents.

Quite appropriate also, was the corresponding English term "Half-Breed" in the first generation of blood mixing, but now that European blood and Indian blood are mingled to varying degrees, it is no longer generally applicable.

The French word Métis expresses the idea of this mixture in as satisfactory a way as possible, and becomes by that fact, a proper race name suitable for our race.

A little observation in passing without offending anyone.

Very polite and amiable people, may sometimes say to a Métis, “You don't look at all like a Métis. You surely can't have much Indian blood. Why, you could pass anywhere for pure White.”

The Métis, a trifle disconcerted by the tone of these remarks, would like to lay claim to both sides of his origin. But fear of upsetting or totally dispelling these kind assumptions holds him back. While he is hesitating to choose among the different replies that come to mind, words like these succeed in silencing him completely. "Ah! bah! You have scarcely any Indian blood. You haven't enough worth mentioning." Here is how the Métis think privately.

"It is true that our Indian origin is humble, but it is indeed just that we honour our mothers as well as our fathers. Why should we be so preoccupied with what degree of mingling we have of European and Indian blood? No matter how little we have of one or the other, do not both gratitude and filial love require us to make a point of saying, 'We are Métis.' "Louis Riel, The Métis, Louis Riel’s Last Memoir, in AH de Tremaudan, l'Histoire de la nation métisse dans l'Ouest[16], translated by Elizabeth Maguet as Hold High Your Heads[17]

Métis people in Canada

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 587,545 (2016) 1.7% of the Canadian population[18] (including persons of partial Métis parentage) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Ojibwe, Cree and Christianity (Protestantism and Catholic)[19][20][21] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

The Métis people in Canada (/meɪˈtiː/; Canadian French: [meˈt͡sɪs], European French: [meˈtis]; Michif: [mɪˈtʃɪf]) are specific cultural communities who trace their descent to First Nations and European settlers, primarily the French, in the early decades of the colonisation of the West. These Métis peoples are recognized as one of Canada's aboriginal peoples under the Constitution Act of 1982, along with First Nations and Inuit peoples. The April 8, 2014 the Supreme Court of Canada Daniels vs Canada appeal held that "Métis and non status Indians are 'Indians' under s. 91(24)", but excluded the Powley test as the only criterion to determine Metis identity. Canadian Métis represent the majority of people that identify as Métis, although there are a number of Métis in the United States. In Canada, the population is 587,545 with 20.5 percent living in Ontario and 19.5 percent in Alberta.[22] The Acadians of eastern Canada, another distinct ethnicity, also has mixed French and Indigenous origins[23], yet are not specifically categorized as Métis, according to Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, the Métis were historically the children of French fur traders and Nehiyaw women of western and central Canada.

While the Métis initially developed as the mixed-race descendants of early unions between First Nations and colonial-era European settlers (usually Indigenous women and French settler men), within generations (particularly in central and western Canada), a distinct Métis culture developed. The women in the unions in eastern Canada or Acadia, were usually Wabanaki and Algonquin, and in Western Canada they were Saulteaux, Cree, Ojibwe, Nakoda and Dakota/Lakota or of mixed descent from these peoples. Their unions with European men engaged in the fur trade in the Old Northwest were often of the type known as marriage à la façon du pays ("according to the custom of the country").[24]

After New France was ceded to Great Britain's control in 1763, there was an important distinction between French Métis born of francophone voyageur fathers and the Anglo-Métis (known as "countryborn" or Mixed Bloods, for instance in the 1870 census of Manitoba) descended from English or Scottish fathers. Today these two cultures have essentially coalesced into location-specific Métis traditions. This does not preclude a range of other Métis cultural expressions across North America.[25][26] Such polyethnic people were historically referred to by other terms, many of which are now considered to be offensive, such as Mixed-bloods, Half-breeds, Bois-Brûlés, Bungi, Black Scots and Jackatars.[27]

While people of Métis culture or heritage are found across Canada, the traditional Métis "homeland" (areas where Métis populations and culture developed as a distinct ethnicity historically) includes much of the Canadian Prairies. The most commonly known group are the "Red River Métis", centring on southern and central parts of Manitoba along the Red River of the North.

Closely related are the Métis in the United States, primarily those in border areas such as Northern Michigan, the Red River Valley and Eastern Montana. These were areas in which there was considerable Aboriginal and European mixing due to the 19th-century fur trade. But they do not have a federally recognized status in the United States, except as enrolled members of federally recognized tribes.[28] Although Métis existed further west than today's Manitoba, much less is known about the Métis of Northern Canada.

Distribution

Data from this section from Statistics Canada, 2016.[29]

| Province / Territory | Percentage of Métis (out of total population) |

|---|---|

| Canada — Total | 1.7% |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1.5% |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.6% |

| Nova Scotia | 2.8% |

| New Brunswick | 1.5% |

| Quebec | 0.8% |

| Ontario | 1.0% |

| Manitoba | 7.3% |

| Saskatchewan | 5.2% |

| Alberta | 2.9% |

| British Columbia | 2.0% |

| Yukon | 2.9% |

| Northwest Territories | 7.1% |

| Nunavut | 0.5% |

Self-identity and legal status

In 2016, 587,545 people in Canada self-identified as Métis. They represented 35.1% of the total Aboriginal population and 1.5% of the total Canadian population.[30] Most Métis people today are descendants of unions between generations of Métis individuals and live in urban areas. The exception are the Métis in rural and northern parts that exist in close proximity to First Nations communities.

Over the past century, countless Métis have assimilated into the general European Canadian populations. Métis heritage (and thereby Aboriginal ancestry) is more common than is generally realized.[31] Geneticists estimate that 50 percent of today's population in Western Canada has some Aboriginal ancestry.[32] Most people with more distant ancestry are not part of the Métis ethnicity or culture.[32]

Unlike among First Nations peoples, there is no distinction between Treaty status and non-Treaty status. The Métis did not sign treaties with Canada, with the exception of an adhesion to Treaty 3 in Northwest Ontario. This adherence was never implemented by the federal government. The legal definition is not yet fully developed. Section Thirty-five of the Constitution Act, 1982 recognizes the rights of Indian, Métis and Inuit people; however, it does not define these groups.[24] In 2003, the Supreme Court of Canada defined a Métis as someone who self-identifies as Métis, has an ancestral connection to the historic Métis community, and is accepted by the modern community with continuity to the historic Métis community.[33]

Historical view of identity

The most well-known and historically documented mixed-ancestry population in Canadian history are the groups who developed during the fur trade in south-eastern Rupert's Land, primarily in the Red River Settlement (now Manitoba) and the Southbranch Settlements (Saskatchewan). In the late nineteenth century, they organized politically (led by men who had European educations) and had confrontations with the Canadian government in an effort to assert their independence.

This was not the only place where métissage (mixing) between European and Indigenous people occurred. It was part of the history of colonization from the earliest days of settlements on the Atlantic Coast throughout the Americas.[34]:2, 5 But the strong sense of ethnic national identity among the mostly French- and Michif-speaking Métis along the Red River, demonstrated during armed resistance movements led by Louis Riel, resulted in wider use of the term "Métis" throughout Canada.

Continued organizing and political activity resulted in "the Métis" gaining official recognition from the national government as one of the recognized Aboriginal groups in S.35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, which states:[35]

35. (1) The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal People of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.

- (2) In this Act, "Aboriginal Peoples of Canada" includes the Indian, Inuit, and Métis Peoples of Canada.

- ...

— Constitution Act, 1982

Section-35(2) does not define criteria for an individual who is Métis. This has left open the question of whether "Métis" in this context should apply only to the descendants of the Red River Métis or to all mixed-ancestry groups and individuals. Many members of First Nations may have mixed ancestry but identify primarily by the tribal nation, rather than as Métis. Since the passage of the 1982 Act, many groups in Canada who are not related to the Red River Métis have adopted the word "Métis" as a descriptor.[34]:7

Lack of a legal definition

It is not clear who has the moral and legal authority to define the word "Métis". There is no comprehensive legal definition of Métis status in Canada; this is in contrast to the Indian Act, which creates an Indian Register for all (Status) First Nations people. Some commentators have argued that one of the rights of an Indigenous people is to define its own identity, precluding the need for a government-sanctioned definition.[34]:9–10 The question is open as to who should receive Aboriginal rights flowing from Métis identity. No federal legislation defines the Métis.

Alberta is the only province to have defined the term in law under the Métis Settlements Act (MSA), which defines a Métis as "a person of Aboriginal ancestry who identifies with Métis history and culture". This was done in the context of creating a test for legal eligibility for membership in one of Alberta's eight Métis settlements. The MSA, together with requirements at the community level (Elder & community acceptance) create the legal requirements for residency on the Métis Settlements. In Alberta law, belonging to a "Métis Association" (Métis National Council or any of its affiliates, Métis Federation of Canada, Congress of Aboriginal People) does not grant one the rights granted to members of the Alberta Métis Settlements. The MSA test excludes those people who are Status Indians (that is, a member of a First Nation), an exclusion which was upheld by the Supreme Court in Alberta v. Cunningham (2011).[34]:10–11

The number of people self-identifying as Métis has risen sharply since the late 20th century: between 1996 and 2006, the population of Canadians who self-identify as Métis nearly doubled, to approximately 390,000.[34]:2 Until R v. Powley (2003), there was no legal definition of Métis other than the legal requirements found in the Métis Settlements Act of 1990.

The Powley case involved a claim by Steven Powley and his son Rodney, two members of the Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario Métis community who were asserting Métis hunting rights. The Supreme Court of Canada outlined three broad factors to identify Métis who have Hunting Rights as Aboriginal peoples:[36]

- self-identification as a Métis individual;

- ancestral connection to an historic Métis community; and

- acceptance by a Métis community.

All three factors must be present for an individual to qualify under the SCC legal definition of Métis. In addition, the court stated that

[t]he term Métis in s. 35 does not encompass all individuals with mixed Indian and European heritage; rather, it refers to distinctive peoples who, in addition to their mixed ancestry, developed their own customs, ways of life, and recognizable group identity separate from their Indian or Inuit and European forebears.[34]:9 The court was explicit that its ten-point test is not a comprehensive definition of Métis.

Questions remain as to whether Métis have treaty rights; this is an explosive issue in the Canadian Aboriginal community today. It has been stated that "only First Nations could legitimately sign treaties with the government so, by definition, Métis have no Treaty rights."[37] One treaty names Métis in the title: the Halfbreed (Métis in the French version) Adhesion to Treaty 3. Another, the Robinson Superior Treaty of 1850, listed 84 persons classified as "half-breeds" in the Treaty, so included them and their descendants.[38] Hundreds, if not thousands, of Métis were initially included in a number of other treaties, and then excluded under later amendments to the Indian Act.[37]

Definitions used by Métis representative organizations

Two main advocacy groups claim to speak for the Métis in Canada: the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples (CAP) and the Métis National Council.(MNC). Each uses different approaches to define Métis individuals. The CAP, which has nine regional affiliates, represents all Aboriginal people who are not part of the reserve system, including Métis and non-Status Indians. It does not define Métis and uses a broad conception based on self-identification.

The Métis National Council broke away from the Native Council of Canada, CAP's predecessor, in 1983. Its political leadership of the time stated that the NCC's "pan-Aboriginal approach to issues did not allow the Métis Nation to effectively represent itself".[34]:11 The MNC views the Métis as a single nation with a common history and culture centred on the fur trade of "west-central North America" in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This position has been subject to much debate and controversy.[39][40]

In 2003 MNC had five provincial affiliates:

- Métis Nation of Ontario Secretariat,

- Manitoba Métis Federation Incorporated,

- Métis Nation of Saskatchewan Association,

- Métis Nation of Alberta Association, and the

- Métis Nation of British Columbia.

The Metis Nation of Alberta Association adopted the following "Definition of Métis":

Métis means a person who self-identifies as a Métis, is distinct from other aboriginal peoples, is of historic Métis Nation ancestry, and is accepted by the Métis Nation.[41]

Several local, independent Métis organizations have been founded in Canada. In Northern Canada neither the CAP nor the MNC have affiliates; here local Métis organizations deal directly with the federal government and are part of the Aboriginal land claims process. Three of the comprehensive settlements (modern treaties) in force in the Northwest Territories include benefits for Métis people who can prove local Aboriginal ancestry prior to 1921 (Treaty 11).[34]:13

The federal government recognizes the Métis National Council as the representative Métis group.[42] In December 2016, Prime Minister Trudeau made a commitment to the leaders of the Assembly of First Nations, the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, and the Métis National Council to have annual meetings. He also committed to two other initiatives aimed at heeding the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) which examined abuses at Indian Residential Schools.[42]

Indigenous Affairs Canada, the relevant federal ministry, deals with the MNC. On April 13, 2017 the two parties signed the Canada-Métis Nation Accord, with the goal of working with the Métis Nation, as represented by the Métis National Council, on a Nation to Nation basis.[43]

In response to the Powley ruling, Métis organizations are issuing Métis Nation citizenship cards to their members. Several organizations are registered with the Canadian government to provide Métis cards.[44] The criteria to receive a card and the rights associated with the card vary with each organization. For example, for membership in the Métis Nation of Alberta Association (MNAA), an applicant must provide a documented genealogy and family tree dating to the mid 1800s, proving descent from one or more members of historic Métis groups.[45]

The Métis Nation of Ontario requires that successful applicants for what it calls "citizenship", must "see themselves and identify themselves as distinctly Métis. This requires that individuals make a positive choice to be culturally and identifiable Métis".[46] They note that "an individual is not Métis simply because he or she has some Aboriginal ancestry, but does not have Indian or Inuit status".[46] It also requires proof of Métis ancestry: "This requires a genealogical connection to a 'Métis ancestor' – not an Indian or aboriginal ancestor".[46]

Cultural definitions

Cultural definitions of Métis identity inform legal and political ones.

The 1996 Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples stated:

Many Canadians have mixed Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal ancestry, but that does not make them Métis or even Aboriginal ... What distinguishes Métis people from everyone else is that they associate themselves with a culture that is distinctly Métis.[34]:12

Traditional markers of Métis culture include use of creole Aboriginal-European languages, such as Michif (French-Cree-Dene) and Bungi (Cree-Ojibwa-English); distinctive clothing, such as the arrow sash (ceinture flêchée); and a rich repertoire of fiddle music, jigs and square dances, and practising a traditional economy based on hunting, trapping, and gathering. But, there is increasing recognition that not all Métis hunted, or wore the sash, or spoke a creole language.[34]:14–15

Origin

During the height of the North American fur trade in New France from 1650 onward, many French and British fur traders married First Nations and Inuit women, mainly Cree, Ojibwa, or Saulteaux located in the Great Lakes area and later into the north west. The majority of these fur traders were French and Scottish; the French majority were Catholic.[32] These marriages are commonly referred to as marriage à la façon du pays or marriage according to the "custom of the country."[47]

At first, the Hudson's Bay Company officially forbade these relationships. However, many Indigenous peoples actively encouraged them, because they drew fur traders into Indigenous kinship circles, creating social ties that supported the economic relationships developing between them and Europeans. When Indigenous women married European men, they introduced them to their people and their culture, taught them about the land and its resources, and worked alongside them. Indigenous women paddled and steered canoes, made moccasins out of moose skin, netted webbing for snowshoes, skinned animals and dried their meat for pemmican, split and dried fish, snared rabbits and partridges, and helped to manufacture birchbark canoes. Intermarriage made the fur trade more successful.[48]

The children of these marriages were often introduced to Catholicism, but grew up in primarily First Nations societies.[48] They were thought of as the familial bond between the Europeans and First Nations and Inuit peoples of North America. As adults, the men often worked as fur-trade company interpreters, as well as fur trappers in their turn.[32] Many of the first generations of Métis lived within the First Nations societies of their wives and children, but also started to marry Métis women.

By the early 19th century, marriage between European fur traders and First Nations or Inuit women started to decline as European fur traders began to marry Métis women instead, because Métis women were familiar with both white and Indigenous cultures, and could interpret.[48]

According to historian Jacob A. Schooley, the Métis developed over at least two generations and within different economic classes. In the first stage, "servant" (employee) traders of the fur trade companies, known as wintering partners, would stay for the season with First Nations bands, and make a "country marriage" with a high-status native woman. This woman and her children would move to live in the vicinity of a trading fort or post, becoming "House Indians" (as they were called by the company men). House Indians eventually formed distinct bands. Children raised within these "House Indian" bands often became employees of the companies. (Foster cites the legendary York boat captain Paulet Paul as an example). Eventually this second-generation group ended employment with the company and became commonly known as "freemen" traders and trappers. They lived with their families raising children in a distinct culture, accustomed to the fur-trade life, that valued free trading and the buffalo hunt in particular. He considered that the third generation, who were sometimes Métis on both sides, were the first true Métis. He suggests that in the Red River region, many "House Indians" (and some non-"House" First Nations) were assimilated into Métis culture due to the Catholic church's strong presence in that region. In the Fort Edmonton region however, many House Indians never adopted a Métis identity but continued to identify primarily as Cree, Saulteaux, Ojibwa, and Chipweyan descendants up until the early 20th century.[49][50]

The Métis played a vital role in the success of the western fur trade. They were skilled hunters and trappers, and were raised to appreciate both Aboriginal and European cultures.[51] Métis understanding of both societies and customs helped bridge cultural gaps, resulting in better trading relationships.[51] The Hudson's Bay Company discouraged unions between their fur traders and First Nations and Inuit women, while the North West Company (the English-speaking Quebec-based fur trading company) supported such marriages. Trappers often married First Nations women too, and operated outside company structures.[52] The Métis peoples were respected as valuable employees of both fur trade companies, due to their skills as voyageurs, buffalo hunters, and interpreters, and their knowledge of the lands.

By the early 1800s European immigrants, mainly Scottish farmers, along with Métis families from the Great Lakes region moved to the Red River Valley in present-day Manitoba.[53][54] The Hudson's Bay Company, which now administered a monopoly over the territory then called Rupert's Land, assigned plots of land to European settlers.[55] The allocation of Red River land caused conflict with those already living in the area, as well as with the North West Company, whose trade routes had been cut in half. Many Métis were working as fur traders with both the North West Company and the Hudson's Bay Company. Others were working as free traders, or buffalo hunters supplying pemmican to the fur trade.[32] The buffalo were declining in number, and the Métis and First Nations had to go farther and further west to hunt them.[56] Profits from the fur trade were declining because of a reduction in European demand due to changing tastes, as well as the need for the Hudson's Bay Company to extend its reach farther from its main posts to get furs.

Most references to the Métis in the 19th century applied to the Plains Métis, but more particularly the Red River Métis.[49] But, the Plains Métis tended to identify by occupational categories: buffalo hunters, pemmican and fur traders, and "tripmen" in the York boat fur brigades among the men;[49] the moccasin sewers and cooks among the women. The largest community in the Assiniboine-Red River district had a different lifestyle and culture from those Métis located in the Saskatchewan, Alberta, Athabasca, and Peace river valleys to the west.[49]

In 1869, two years after Canadian Confederacy, the Government of Canada exerted its power over the people living in Rupert's Land after it acquired the land in the mid-19th century from the Hudson's Bay Company.[57] The Métis and the Anglo-Métis (commonly known as Countryborn, children of First Nations women and Orcadian, other Scottish or English men),[58] joined forces to stand up for their rights. They wanted to protect their traditional ways of life against an aggressive and distant Anglo-Canadian government and its local colonizing agents.[55] An 1870 census of Manitoba classified the population as follows: 11,963 total people. Of this number 558 were defined as Indians (First Nations). There were 5,757 Métis and 4,083 English-speaking Mixed Bloods. The remaining 1,565 people were of predominately European, Canadian or American background.[59]

During this time the Canadian government signed treaties (known as the "Numbered Treaties") with various First Nations. These Nations ceded property rights to almost the entire western plains to the Government of Canada. In return for their ceding traditional lands, the Canadian government promised food, education, medical help, etc.[60] While the Métis generally did not sign any treaty as a group, they were sometimes included, even listed as "half-breeds" in some records.

In the late 19th century, following the British North America Act (1867), Louis Riel, a Métis who was formally educated, became a leader of the Métis in the Red River area. He denounced the Canadian government surveys on Métis lands [61] in a speech delivered in late August 1869 from the steps of Saint Boniface Cathedral.[32] The Métis became more fearful when the Canadian government appointed the notoriously anti-French William McDougall as the Lieutenant Governor of the Northwest Territories on September 28, 1869, in anticipation of a formal transfer of lands to take effect in December.[32] On November 2, 1869 Louis Riel and 120 men seized Upper Fort Garry, the administrative headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company. This was the first overt act of Métis resistance.[61] On March 4, 1870 the Provisional Government, led by Louis Riel, executed Thomas Scott after Scott was convicted of insubordination and treason.[62][63] The elected Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia [64] subsequently sent three delegates to Ottawa to negotiate with the Canadian government. This resulted in the Manitoba Act and that province's entry into the Canadian Confederation. Due to the execution of Scott, Riel was charged with murder and fled to the United States in exile.[55]

In March 1885, the Métis heard that a contingent of 500 North-West Mounted Police was heading west.[65] They organized and formed the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan, with Pierre Parenteau as President and Gabriel Dumont as adjutant-general. Riel took charge of a few hundred armed men. They suffered defeat by Canadian armed forces in a conflict known as the North West Rebellion, which occurred in northern Saskatchewan from March 26 to May 12, 1885.[55] Gabriel Dumont fled to the United States, while Riel, Poundmaker, and Big Bear surrendered. Big Bear and Poundmaker each were convicted and received a three-year sentence. On July 6, 1885, Riel was convicted of high treason and was sentenced to hang. Riel appealed but he was executed on November 16, 1885.[55]

Land ownership

Issues of land ownership became a central theme, as the Métis sold most of the 600,000 acres they received in the first settlement.[66][67]

During the 1930s, political activism arose in Métis communities in Alberta and Saskatchewan over land rights, and some filed land claims for the return of certain lands.[68] Five men, sometimes dubbed "The Famous Five", (James P. Brady, Malcolm Norris, Peter Tomkins Jr., Joe Dion, Felix Callihoo) were instrumental in having the Alberta government form the 1934 "Ewing Commission", headed by Albert Ewing, to deal with land claims.[69] The Alberta government passed the Métis Population Betterment Act in 1938.[69] The Act provided funding and land to the Métis. (The provincial government later rescinded portions of the land in certain areas.)[69]

Métis settlements of Alberta – a distinct Métis identity

_Flag.gif)

- OUR PEOPLE, OUR LAND, OUR CULTURE, OUR FUTURE – Métis Settlements Motto

The Métis settlements in Alberta are the only recognized land base of Métis in Canada. They are represented and governed collectively by a unique Métis government known as the Métis Settlements General Council (MSGC),[70] also known as the "All-Council". The MSGC is the provincial, national, and international representative of the Federated Métis Settlements. It holds fee simple land title via Letters Patents to 1.25 million acres of land, making the MSGC the largest land holder in the province, other than the Crown in the Right of Alberta. The MSGC is the only recognized Métis Government in Canada with prescribed land, power, and jurisdiction via the Métis Settlements Act. (This legislation followed legal suits filed by the Métis Settlements against the Crown in the 1970’s).

The Métis settlements consist of predominantly Indigenous Métis populations native to Northern Alberta – unique from those of the Red River, the Great Lakes, and other migrant Métis from further east. However, following the Riel and Dumont resistances some Red-River Métis fled westward, where they married into the contemporary Métis settlement populations during the end of the 19th century and into the early 20th century. Historically referred to as the "Nomadic Half-breeds", the Métis of Northern Alberta have a unique history. Their fight for land is still evident today with the eight contemporary Métis settlements.

Following the formal establishment of the Métis settlements, then called Half-Breed Colonies, in the 1930s by a distinct Métis political organization, the Métis populations in Northern Alberta were the only Métis to secure communal Métis lands. During renewed Indigenous activism during the 1960s into the 1970s, political organizations were formed or revived among the Métis. In Alberta, the Métis settlements united as: The "Alberta Federation of Métis Settlement Associations" in the mid-1970s. Today, the Federation is represented by the Métis Settlements General Council.[71]

During the constitutional talks of 1982, the Métis were recognized as one of the three Aboriginal peoples of Canada, in part by the Federation of Métis Settlements. In 1990, the Alberta government, following years of conferences and negotiations between the Federation of Métis Settlements (FMS) and the Crown in the Right of Alberta, restored land titles to the northern Métis communities through the Métis Settlement Act, replacing the Métis Betterment Act.[69] Originally the first Métis settlements in Alberta were called colonies and consisted of:

- Buffalo Lake (Caslan) or Beaver River

- Cold Lake

- East Prairie (south of Lesser Slave Lake)

- Elizabeth (east of Elk Point)

- Fishing Lake (Packechawanis)

- Gift Lake (Ma-cha-cho-wi-se) or Utikuma Lake

- Goodfish Lake

- Kikino

- Kings Land

- Marlboro

- Paddle Prairie (or Keg River)

- Peavine (Big Prairie, north of High Prairie)

- Touchwood

- Wolf Lake (north of Bonnyville)

In the 1960s, the settlements of Marlboro, Touchwood, Cold Lake, and Wolf Lake were dissolved by Order-in-Council by the Alberta Government. The remaining Métis Settlers were forced to move into one of the eight remaining Métis Settlements – leaving the eight contemporary Métis Settlements.

The position of Federal Interlocutor for Métis and Non-Status Indians was created in 1985 as a portfolio in the Canadian Cabinet.[72] The Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development is officially responsible only for Status Indians and largely with those living on Indian reserves. The new position was created in order provide a liaison between the federal government and Métis and non-status Aboriginal peoples, urban Aboriginals, and their representatives.[72]

Organizations

The Provisional Government of Saskatchewan was the name given by Louis Riel to the independent state he declared during the North-West Rebellion (Resistance) of 1885 in what is today the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. The governing council was named the Exovedate, Latin for "of the flock".[73] The council debated issues ranging from military policy to local bylaws and theological issues. It met at Batoche, Saskatchewan, and exercised real authority only over the Southbranch Settlement. The provisional government collapsed that year after the Battle of Batoche.

The Métis National Council was formed in 1983, following the recognition of the Métis as an Aboriginal Peoples in Canada, in Section Thirty-five of the Constitution Act, 1982. The MNC was a member of the World Council of Indigenous (WCIP). In 1997 the Métis National Council was granted NGO Consultative Status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council. The MNC's first ambassador to this group was Clement Chartier. MNC is a founding member of the American Council of Indigenous Peoples (ACIP).[74]

The Métis National Council is composed of five provincial Métis organizations,[75] namely,

- Métis Nation British Columbia

- Métis Nation of Alberta

- Métis Nation-Saskatchewan

- Manitoba Métis Federation

- Métis Nation of Ontario

The Métis people hold province-wide ballot box elections for political positions in these associations, held at regular intervals, for regional and provincial leadership. Métis citizens and their communities are represented and participate in these Métis governance structures by way of elected Locals or Community Councils, as well as provincial assemblies held annually.[76]

The Congress of Aboriginal Peoples (CAP) and its nine regional affiliates represent all Aboriginal people who are not part of the reserve system, including Métis and non-Status Indians.

Due to political differences to the MNBC, a separate Métis organization in British Columbia was formed in June 2011; it is called the British Columbia Métis Federation (BCMF).[77] They have no affiliation with the Métis National Council and have not been officially recognized by the government.

The Canadian Métis Council–Intertribal is based in New Brunswick and is not affiliated with the Métis National Council.[78]

The Ontario Métis Aboriginal Association–Woodland Métis is based in Ontario and is not affiliated with the Métis National Council. Its representatives think the MNC is too focused on the Métis of the prairies.[79] The Woodland Métis are also not affiliated with the Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) and MNO President Tony Belcourt said in 2005 that he did not know who OMAA members are, but that they are not Métis.[80] In a Supreme Court of Canada appeal (Document C28533, page 17), the federal government states that "membership in OMAA and/or MNO does not establish membership in the specific local aboriginal community for the purposes of establishing a s. 35 [Indigenous and treaty] right. Neither OMAA nor the MNO constitute the sort of discrete, historic and site-specific community contemplated by Van der Peet capable of holding a constitutionally protected aboriginal right".[81]

The Nation Métis Québec is not affiliated with the Métis National Council.[82]

None of these claim to represent all Métis. Other Métis registry groups also focus on recognition and protection of their culture and heritage. They reflect their communities' particular extensive kinship ties and culture that resulted from settlement in historic villages along the fur trade.

Culture

Language

A majority of the Métis once spoke, and many still speak, either Métis French or an Indigenous language such as Mi'kmaq, Cree, Anishinaabemowin, Denésoliné, etc. A few in some regions spoke a mixed language called Michif which is composed of Plains Cree verbs and French nouns. Michif, Mechif or Métchif is a phonetic spelling of the Métis pronunciation of Métif, a variant of Métis.[83] The Métis today predominantly speak Canadian English, with Canadian French a strong second language, as well as numerous Aboriginal tongues.[84] Métis French is best preserved in Canada.

Michif is most used in the United States, notably in the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation of North Dakota. There Michif is the official language of the Métis who reside on this Chippewa (Ojibwe) reservation.[85] After years of decline in use of these languages, the provincial Métis councils are encouraging their revival, teaching in schools and use in communities. The encouragement and use of Métis French and Michif is growing due to outreach after at least a generation of decline.[86]

The 19th-century community of Anglo-Métis, more commonly known as Countryborn, were children of people in the Rupert's Land fur trade; they were typically of Orcadian, other Scottish, or English paternal descent and Aboriginal maternal descent.[86] Their first languages would have been Aboriginal (Cree language, Saulteaux language, Assiniboine language, etc.) and English. The Gaelic and Scots spoken by Orcadians and other Scots became part of the creole language referred to as "Bungee".[87]

Flag

The Métis flag is one of the oldest patriotic flags originating in Canada.[88] The Métis have two flags. Both flags use the same design of a central infinity symbol, but are different colours. The red flag was the first flag used. It is currently the oldest flag made in Canada that is still in use. The first red flag was given to Cuthbert Grant in 1815 by the North-West Company as reported by James Sutherland. Days before the Battle of Seven Oaks, "La Grenouillère" in 1816, Peter Fidler recorded Cuthbert Grant flying the blue flag. The red and blue are not cultural or linguistic identifiers and do not represent the companies.[88]

Distinction of lowercase m versus uppercase M

The term "Métis" is originally a French word used to refer to mixed-race children of the union of French colonists from France and women from the colonized area, throughout France's worldwide colonies.[6][8] The first records of "Métis" were made by 1600 on the East Coast of Canada (Acadia), where French exploration and settlement started.

As French Canadians followed the fur trade to the west, they made more unions with different First Nations women, including the Cree. Descendants of English or Scottish and natives were historically called "half-breeds" or "country born". They sometimes adopted a more agrarian culture of subsistence farming and tended to be reared in Protestant denominations.[89] The term eventually evolved to refer to all 'half-breeds' or persons of mixed First Nations-European ancestry, whether descended from the historic Red River Métis or not.

Lowercase 'm' métis refers to those who are of mixed native and other ancestry, recognizing the many people of varied racial ancestry. Capital 'M' Métis refers to a particular sociocultural heritage and an ethnic self-identification that is based on more than racial classification.[90] Some argue that people who identify as métis should not be included in the definition of 'Métis'. Others view this distinction as recent, artificial, and offensive, criticized for creating from what are newly imagined and neatly defined ethnological boundaries, justification to exclude "other Métis".

Some Métis have proposed that only the descendants of the Red River Métis should be constitutionally recognized, as they had developed the most distinct culture as a people in historic times.[91] There have been claims made that such a limitation would result in excluding some of the Maritime, Quebec, and Ontario Métis, classifying them simply by the lowercase m métis status. In a recent decision (Daniels v Canada (Indian Affairs and Northern Development) 2016 SCC 12), the Supreme Court of Canada has stated in para 17:[92]

[17] There is no consensus on who is considered Métis or a non-status Indian, nor need there be. Cultural and ethnic labels do not lend themselves to neat boundaries. ‘Métis’ can refer to the historic Métis community in Manitoba’s Red River Settlement or it can be used as a general term for anyone with mixed European and Aboriginal heritage. Some mixed-ancestry communities identify as Métis, others as Indian:

- There is no one exclusive Métis People in Canada, anymore than there is no one exclusive Indian people in Canada. The Métis of eastern Canada and northern Canada are as distinct from Red River Métis as any two peoples can be ... As early as 1650, a distinct Métis community developed in LeHeve [sic], Nova Scotia, separate from Acadians and Micmac Indians. All Métis are aboriginal people. All have Indian ancestry.:12

Distribution

According to the 2016 Canada Census, a total of 587,545 individuals self-identified as Métis.[93] However, it is doubtful that all such individuals would meet the objective tests laid out in the Supreme Court decisions Powley and Daniels and therefore qualify as "Métis" for the purposes of Canadian law.

Genocide

In 2019, the final report, Reclaiming Power and Place,[94] by the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls stated “The violence the National Inquiry heard amounts to a race-based genocide of Indigenous Peoples, including First Nations, Inuit and Métis, which especially targets women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people.”

Métis people in the United States

| |

Paul Kane's oil painting Half-Breeds Running Buffalo, depicting a Métis buffalo hunt on the prairies of Dakota in June 1846. | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| |

| Languages | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

|

The Métis people in the United States are a specific culture and community of Métis people, who descend from unions between Native American and early European colonist parents - usually Indigenous women who married French (and later Scottish or English) men who worked as fur trappers and traders during the 18th and 19th centuries at the height of the fur trade. They developed as an ethnic and cultural group from the descendants of these unions. The women were usually Algonquian, Ojibwe and Cree.

In the French colonies, people of mixed Indigenous and French ancestry were referred to by those who spoke French as métis, as it means "mixture".

Being bilingual, these people were able to trade European goods, such as muskets, for the furs and hides at a trading post. These métis were found through the Great Lakes area and to the Rocky Mountains. While the word in this usage originally had no ethnic designation (and was not capitalized in English), it grew to become an ethnicity in the 19th century. This use (of simply meaning "mixed") excludes mixed-race people born of unions in other settings or more recently than about 1870.

The Métis in the U.S. are fewer in number than the neighboring Métis in Canada. During the early colonial era, the border did not exist between Canada and the British colonies and people moved easily back and forth through the area. While the two communities come from the same origins, the Canadian Métis have developed further as an ethnic group than in the U.S.

As of 2018, Métis people were living in Michigan, Illinois, Ohio, Minnesota, North Dakota and Montana.[95]

Geography

With exploration, settlement and exploitation of resources by French and British fur trading interests across North America, European men often had relationships and sometimes marriages with Native American women. Often both sides felt such marriages were beneficial in strengthening the fur trade. Indigenous women often served as interpreters and could introduce their men to their people. Because many Native Americans and First Nations often had matrilineal kinship systems, the mixed-race children were considered born to the mother's clan and usually raised in her culture. Fewer were educated in European schools. Métis men in the northern tier typically worked in the fur trade and later hunting and as guides. Over time in certain areas, particularly the Red River of the North, the Métis formed a distinct ethnic group with its own culture.

History

Between 1795 and 1815, a network of Métis settlements and trading posts was established throughout what is now the US states of Michigan and Wisconsin and to a lesser extent in Illinois and Indiana. As late as 1829, the Métis were dominant in the economy of present-day Wisconsin and Northern Michigan.[96]

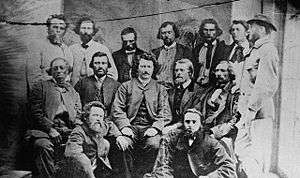

.jpg)

Date of Original: 1883

Credit Line: State Historical Society of North Dakota (A4365)

During the early days of territorial Michigan, Métis and French played a dominant role in elections. It was largely with Métis support that Gabriel Richard was elected as delegate to Congress. After Michigan was admitted as a state and under pressure of increased European-American settlers from eastern states, many Métis migrated westward into the Canadian Prairies, including the Red River Colony and the Southbranch Settlement. Others identified with Chippewa groups, while many others were subsumed in an ethnic "French" identity, such as the Muskrat French. By the late 1830s only in the area of Sault Ste. Marie was there widespread recognition of the Métis as a significant part of the community.[97]

Another major Métis settlement was La Baye, located at the present site of Green Bay, Wisconsin. In 1816 most of its residents were Métis.[98]

In Montana a large group of Métis from Pembina region hunted there in the 1860s, eventually forming an agricultural settlement in the Judith Basin by 1880. This settlement eventually disintegrated, with most Métis leaving or identifying more strongly either as "white" or "Indian".[99]

Metis often participated in interracial marriages. The French in specific, viewed these marriages as sensible and realistic. Americans, however, viewed interracial marriages as unsound as the idea of racial purity was seen as the only option. Although it was legal, the result of these marriages generally resulted in the loss of status for the spouse of the highest social class, as well as for any children produced during the marriage. The French, however, seemed to motivate fur traders to participate in interracial marriages with Indian tribes as they helped to be beneficial to the fur trade business and also to spread religion. Generally speaking, these marriages were happy ones, that lasted and brought together differing groups of people and benefitted the fur trade business.[100][101]

Current population

Mixed-race people live throughout Canada and the northern United States but only some in the US identify ethnically and culturally as Métis. A strong Prairie Métis identity exists in the "homeland" once known as Rupert's Land, which extends south from Canada into North Dakota, especially the land west of the Red River of the North. The historic Prairie Métis homeland also includes parts of Minnesota, and Wisconsin. A number of self-identified Métis live in North Dakota, mostly in Pembina County.[102] Many members of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians (a federally recognized Tribe) identify as Métis or Michif rather than as strictly Ojibwe.[103]

Many Métis families are recorded in the U.S. Census for the historic Métis settlement areas along the Detroit and St. Clair rivers, Mackinac Island and Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, as well as Green Bay in Wisconsin. Their ancestral families were often formed in the early 19th-century fur trading era.

The Métis have generally not organized as an ethnic or political group in the United States as they have in Canada, where they had armed confrontations in an effort to secure a homeland.

The first "Conference on the Métis in North America" was held in Chicago in 1981,[104] after increasing research about this people. This also was a period of increased appreciation for different ethnic groups and reappraisal of the histories of settlement of North America. Papers at the conference focused on "becoming Métis" and the role of history in formation of this ethnic group, defined in Canada as having Aboriginal status. The people and their history continue to be extensively studied, especially by scholars in Canada and the United States.

These are to be distinguished with other 'tri-racial isolate' groups such as the Munguelons, Rampao Mountain People, the We-Sort, the Brass Ankles, the Red Bones, etc.

Louis Riel and the United States

Louis Riel had a significant impact on the Métis community in Canada, especially in the Manitoba region. However he did also have a distinct relationship with the Métis in the United States and was in fact at the time of his execution an American citizen.[105] Riel attempted to be a leader for the Métis community in the United States and contributed immensely in the defence of the Métis rights, especially those who occupied the Red River region throughout his life.

On October 22, 1844 Louis Riel was born in the Red River settlement known as the territory of Assiniboia.[105] He was born with British background however as the Métis are a mobile community he travelled a lot and had a transitional identity, meaning he would often cross the Canada and United States border. During the 19th century there were few American born citizens living in Red River altogether.

Riel greatly contributed to the defense of Métis justice, more specifically on November 22, 1869 Riel arrived in Winnipeg to discuss with McDougall the rights of the Métis community. At the end of the settlement McDougall agreed to guarantee a “List of Rights”.[105] That statement also incorporated four clauses of the Dakota bill of rights. This Bill of rights was the rise of the American Métis influence during the Red River Métis revolution and was an important milestone in Métis justice.

The following years saw a constant battle between the government in charge and the Métis people that furthermore created conflict involving citizenship of Métis leaders, such as Louis Riel who was crossing the border without proper notice. This caused repercussions for Riel who was now wanted by the Ontario government. He was later accused for the Scott Death, a murder case which was decided without a proper trial and by 1874 there was a warrant out for his arrest in Winnipeg.[105] Because of the warrant accusations in Canada, Riel saw the United States as a safer territory for himself and the Métis people. The following years led to Riel running from the Canadian government because of the murder convictions and this is when he spent most of his time in the United States. Riel struggled with mental health problems and decided in the following years that it was time to receive proper treatment in the American northeast from 1875-1878. Once better decided to change his life by obtaining an American residence and decided to complete the journey of the liberation of the Métis people that he first started in 1869. With the help of the United States military, Riel wanted to invade Manitoba to obtain control. However, because of the lack of desire to cause conflict with the Canadian military the American military rejected his proposition. He then tried to create an international alliance between the Aboriginal and Metis people, which wasn't a success either. In the end his main objective was to simply improve the living conditions and rights of the Métis people in the United States. The failed attempts for Riel to defend the Métis community lead to further mental breakdowns and hospitalization, now in Quebec.[105]

Riel returned to Montana from 1879 to continue on his mission to defend the Métis community in the United States. Riel wanted the Métis and the Native people of the region to join forces and create a political movement against the provisional government. Both parties denied this profound movement and after yet another failed attempt to create a revolution he decided to officially become an American citizen and declared “The United States sheltered me, The English didn’t care/what they owe they will pay/! I am citizen”.[105] He then spent the next four years improving the conditions of the Montana Métis in any way he could.

Riel stayed in the United States from 1880-1884 fighting to obtain official residency from the American government but without success he finally departed for Saskatchewan in 1884. Riel concentrated his public life on improving the situation of the Montana Metis and had a big impact on the Métis people in the United States by attempting to address their rights and improve overall living conditions. The following years was a constant battle to obtain official citizenship from the American government. In the end, an American citizenship did not permit the protection from Canadian convictions. The American officials did not confirm his American citizenship because of fear of further conflict with the Canadian government and confirmed Riel's execution for treason in 1885.[105]

The Medicine Line (Canada–U.S. Border)

The Métis homeland existed before the implementation of the Canada–U.S. border and continues to exist on both sides of this border today. The implementation of the border affected the Métis in a multitude of ways, with border enforcement growing from relaxed to increasingly stronger over time.[106] In the late 18th century, to early 19th century the Métis found that in times of conflict, they could cross the 49th parallel North in either direction and the trouble following them would stop and so the border was known as the Medicine Line. This began to change toward the end of the 19th century when the border became more enforced and the Canadian government saw an opportunity to put an end to the line hopping by using military force.[106] This effectively split some of the Métis population and restricted the mobility of the People. The enforcement of the border was used as a means for governments on either side of the Medicine Line in the grand prairies to control the Métis population and to restrict their access to buffalo.[106] Because of the importance of kinship and mobility for Métis communities,[14] this had negative implications and resulted in different experiences and hardships for both groups.

Métis experience in the U.S. is largely coloured by unratified treaties and the lack of federal representation of Métis communities as a legitimate people, and this can be seen in the case of the Little Shell Tribe in Montana.[107] While experiences in Canada are also effected by the misrecognition of the Métis, many Métis were dispossessed of their lands when they were sold to settlers and some community set up Road Allowance villages. These small villages were squatter's villages along Crown land outside of established villages in the prairies of Canada.[108] These villages were often burned by local authorities and had to be rebuilt by surviving members of the communities that lived in them.

See also

Further reading

- Andersen, C. (2011). Moya `Tipimsook (“The People Who Aren't Their Own Bosses”): Racialization and the Misrecognition of “Métis” in Upper Great Lakes Ethnohistory. Ethnohistory, 58(1), 37-63. doi:10.1215/00141801-2010-063

- Andersen, C. (2014). More Than the Sum of Our Rebellions: Métis Histories Beyond Batoche. Ethnohistory, 61(4), 619-633. doi:10.1215/00141801-2717795

- Barkwell, L. (n.d.). Metis Political Organizations. Retrieved from http://www.metismuseum.ca/media/db/11913

- Flanagan, T. (1990). The History of Metis Aboriginal Rights: Politics, Principle, and Policy. Canadian Journal of Law and Society, 5, 71-94. doi:10.1017/S0829320100001721

- Hogue, M. (2002). Disputing the Medicine Line: The Plains Crees and the Canadian-American Border, 1876- 1885. Montana: The Magazine of Western History, 52(4), 2–17.

- Sawchuck, J. (2001). Negotiating an Identity: Métis Political Organizations, the Canadian Government, and Competing Concepts of Aboriginality. American Indian Quarterly, 25(1), 73–92.

- St-Onge, N., Macdougall, B., & Podruchny, C. (Eds.). (2012). Contours of a People: Metis family, mobility, and history. Chapter 2, 22-58. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

- Canada

- Andersen, Chris (2014) "Metis": Race, Recognition and the Struggle for Indigenous Peoplehood. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Barkwell, Lawrence J. (2016), The Metis homeland: its settlements and communities. Winnipeg, Manitoba: Louis Riel Institute. ISBN 978-1-927531129.

- Barkwell, Lawrence J. (2010). The Battle of Seven Oaks: a Métis perspective. Winnipeg, Manitoba: Louis Riel Institute. ISBN 978-0-9809912-9-1.

- Barkwell, Lawrence J. (2011). Veterans and Families of the 1885 Northwest Resistance. Saskatoon: Gabriel Dumont Institute. ISBN 978-1-926795-03-4

- Hogue, Michel (2015). Métis and the Medicine Line: Creating a Border and Dividing a People. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Huel, Raymond Joseph Armand (1996), Proclaiming the Gospel to the Indians and the Métis, University of Alberta Press, ISBN 0-88864-267-9

- Martha Harroun, Foster (2006), We Know Who We Are: Métis Identity in a Montana Community, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0806137053

- James Rodger Miller, "From Riel to the Métis" (2004). Reflections on Native-newcomer Relations: Selected Essays. University of Toronto Press. pp. 37–60., historiography

- Peterson, Jacqueline; Brown, Jennifer S.H. (2001), The New Peoples: Being and Becoming Métis in North America, Minnesota Historical Society Press, ISBN 0-87351-408-4

- Quan, Holly (2009), Native Chiefs and Famous Métis: Leadership and Bravery in the Canadian West, Heritage House, ISBN 978-1-894974-74-5

- Sprague, Douglas N (1988), Canada and the Métis, 1869–1885, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, ISBN 0-88920-958-8

- Wall, Denis (2008), The Alberta Métis letters, 1930–1940: policy review and annotations, DWRG Press, ISBN 978-0-9809026-2-4

- Sylvia Van Kirk (1983). Many Tender Ties: Women in Fur-Trade Society, 1670–1870. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-1847-5.

- Marcel, Giraud (1984), Le Métis canadien / Marcel Giraud ; introduction du professeur J.E. Foster avec Louise Zuk (in French), Saint-Boniface, Man. : Éditions du Blé, 1984., ISBN 0920640451

Teillet, Jean. : The North-West is Our Mother-The Story of Louis Riel's People, The Metis Nation, 2019

- United States

- Barkwell, Lawrence J., Leah Dorion, and Audreen Hourie. Metis legacy Michif culture, heritage, and folkways. Metis legacy series, v. 2. Saskatoon, SK: Gabriel Dumont Institute, 2006.

- Barkwell, Lawrence J., Leah Dorion and Darren Prefontaine. Metis Legacy: A Historiography and Annotated Bibliography. Winnipeg, MB: Pemmican Publications and Saskatoon: Gabriel Dumont Institute, 2001.

- Foster, Harroun Marther. We Know Who We Are: Métis Identity in a Montana Community. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006.

- Peterson, Jacqueline and Jennifer S. H. Brown, ed. The New Peoples: Being and Becoming Metis in North America. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001.

- St-Onge, Nicole, Carolyn Podruchny, and Brenda Macdougall (eds.), Contours of a People: Metis Family, Mobility, and History. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012.

References

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics (2013-05-08). "The Daily — 2011 National Household Survey: Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: First Nations People, Métis and Inuit". www.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- "The Daily — Aboriginal peoples in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census". 2017-10-25.

- Peterson, Jacqueline; Brown, Jennifer S. H. (2001) "Introduction". In The New Peoples: Being and Becoming Métis in North America, pp. 3–18. Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 0873514084.

- Rea, J.e., Scott, Jeff (April 6, 2017). "Manitoba Act". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- "Métis Relations". alberta.ca. Province of Alberta. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "Metis". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Robert, Paul (1973). Dictionnaire alphabétique et analogique de la langue française. Paris: Dictionnaire LE ROBERT. ISBN 978-2-321-00858-3.

- "MÉTIS : Etymologie de MÉTIS" [Etymology of MÉTIS]. Ortolang (in French). Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- James Alexander, Simone A. (2001). Mother Imagery in the Novels of Afro-Caribbean Women. University of Missouri Press. pp. 14–5. ISBN 082626316X.

- Jones, Hilary (2013). The Métis of Senegal: Urban Life and Politics in French West Africa. Indiana University Press. p. 296. ISBN 978-0253007056.

- Lorcin, Patricia M. E. (2006). Algeria & France, 1800–2000: Identity, Memory, Nostalgia. Syracuse University Press. pp. 80–1. ISBN 0815630743.

- Robson, Kathryn and Jennifer Yee (2005). France and "Indochina": Cultural Representations. Lexington Books. pp. 210–1. ISBN 0739108409.

- Flanagan, Thomas E. (1990/ed). "The History of Metis* Aboriginal Rights: Politics, Principle, and Policy". Canadian Journal of Law & Society / La Revue Canadienne Droit et Société. 5: 71–94. doi:10.1017/S0829320100001721. ISSN 1911-0227. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Contours of a people : Metis family, mobility, and history. St-Onge, Nicole., Podruchny, Carolyn., Macdougall, Brenda, 1969-. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 2012. ISBN 978-0-8061-4279-1. OCLC 790269782.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Andersen, Chris (2011-01-01). "Moya 'Tipimsook ("The People Who Aren't Their Own Bosses"): Racialization and the Misrecognition of "Métis" In Upper Great Lakes Ethnohistory". Ethnohistory. 58 (1): 37–63. doi:10.1215/00141801-2010-063. ISSN 0014-1801.

- de Tremaudan, Auguste-Henri (1936). l'Histoire de la nation métisse dans l'Ouest Canadien (in French). Montreal: Éditions Albert Lévesque. pp. 434–5. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- de Tremaudan, Auguste-Henri (1982). Hold High Your Heads: History of the Metis Nation in Western Canada. Translated by Maguet, Elizabeth. Winnipeg: Pemmican Publications. p. 200.

- "First Nations People, Métis and Inuit". 12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 2018-03-21.

- contenu, English name of the content author / Nom en anglais de l'auteur du. "English title / Titre en anglais". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- "The Métis". Canada's First Peoples. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "Métis". Facing History and Ourselves. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- Morin, Brandi (10 March 2020). "The Back Streeters and the White Boys: Racism in rural Canada". Al Jazeera website Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- Pritchard, James; Pritchard, Pritchard, James S.; Pritchard, Professor James (2004-01-22). In Search of Empire: The French in the Americas, 1670-1730. Cambridge University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-521-82742-3.

Abbé Pierre Maillard claimed that racial intermixing had proceeded so far by 1753 that in fifty years it would be impossible to distinguish Amerindian from French in Acadia.

- Barkwell, Lawrence J., Leah Dorion and Darren Préfontaine. Métis Legacy: A Historiography and Annotated Bibliography. Winnipeg: Pemmican Publications Inc. and Saskatoon: Gabriel Dumont Institute, 2001. ISBN 1-894717-03-1

- "What to Search: Topics - Genealogy and Family History - Library and Archives Canada". 6 October 2014. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- Rinella, Steven. 2008. American Buffalo: In Search of A Lost Icon. NY: Spiegel and Grau.

- McNab, David; Lischke, Ute (2005). Walking a Tightrope: Aboriginal People and their Representations. ISBN 9780889204607.

- Howard, James H. 1965. "The Plains-Ojibwa or Bungi: hunters and warriors of the Northern Prairies with special reference to the Turtle Mountain band"; University of South Dakota Museum Anthropology Papers 1 (Lincoln, Nebraska: J. and L. Reprint Co., Reprints in Anthropology 7, 1977).

- "2016 Census of Canada: Topic-based tabulations | Ethnic Origin (247), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census - 20% Sample Data". Statistics Canada. 2020-01-11. Retrieved 2020-01-11.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics. "Aboriginal identity population, Canada, 2016". www150.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- Barkwell, Lawrence J., Leah Dorion and Darren Préfontaine. Métis Legacy: A Historiography and Annotated Bibliography. Winnipeg: Pemmican Publications Inc. and Saskatoon: Gabriel Dumont Institute, 2001. ISBN 1-894717-03-1

- "Complete History of the Canadian Métis Culturework=Métis nation of the North West".

- Lambrecht, Kirk N. (2013). Aboriginal Consultation, Environmental Assessment, and Regulatory Review in Canada. University of Regina Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-88977-298-4.

- Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples. "The People Who Own Themselves" Recognition of Métis Identity in Canada (PDF) (Report). Canadian Senate. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- "Rights of the Aboriginal People of Canada". Canadian Department of Justice.

- (2003), 230 D.L.R. (4th) 1, 308 N.R. 201, 2003 SCC 43 [Powley]

- McNab, David, and Ute Lischke. The Long Journey of a Forgotten People: Métis Identities and Family Histories. Waterloo, Ont: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-88920-523-9

- Morris, Alexander. The Treaties of Canada with the Indians of Manitoba and the North West Territories Including the Negotiations on which They Were. Belfords, Clarke & Co., 1880

- "Métis are a People, not a historical process". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- "The "Other" Métis". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- Definition of Métis Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine

- "Trudeau pledges annual meetings with Indigenous leaders to advance reconciliation". Retrieved 15 November 2018 – via The Globe and Mail.

- "Canada-Metis Nation Accord". 20 April 2017. Archived from the original on 15 November 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- Aboriginal Canada Portal – Métis Card Archived 2013-02-05 at the Wayback Machine

- "MNA membership" Archived 2013-11-06 at the Wayback Machine, Métis Nation of Alberta Metis

- http://www.metisnation.org/media/83726/mno_interim_registry_package.pdf

- Friesen, Gerald (1987). The Canadian Prairies. Toronto: Toronto University Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-8020-6648-8.

- Van Kirk, Sylvia (1984). "The Role of Native Women in the Fur Trade Society of Western Canada, 1670-1830" (PDF). Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 7: 9–13 – via JSTOR.

- Foster, John E. (1985). "Paulet Paul: Métis or "House Indian" Folk-Hero?". Manitoba History. Manitoba Historical Society. 9: Spring. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- Binnema, et al. "John Elgin Foster", From Rupert's Land to Canada: Essays in Honour of John E. Foster pp ix–xxii

- "The Métis Nation". Angelhair. Archived from the original on 2009-08-01.

- "Who are the METIS?". Métis National Council. Archived from the original on 2010-02-26.

- "Canada A Country by Consent: Manitoba Joins Confederation: The Métis". www.canadahistoryproject.ca.

- Arthur J. Ray (2016). Aboriginal Rights Claims and the Making and Remaking of History. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 210–212. ISBN 978-0-7735-4743-8.

- "Riel and the Métis people" (PDF). The departments of Advanced Education and Literacy, Competitiveness, Training and Trade, and Education, Citizenship and Youth. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-11-22. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- "A Brief History of the Métis People". Wolf Lodge Cultural Foundation ~ Golden Braid Ministries. Archived from the original on 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- Gillespie, Greg (2007). Hunting for Empire Narrative of Sport in Rupert's Land, 1840–70. Vancouver, BC, Canada: UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-1354-9

- Jackson, John C. Children of the Fur Trade: Forgotten Métis of the Pacific Northwest. Corvallis: Oregon State Univ Press, 2007. ISBN 0-87071-194-6

- The Metis", Alberta Settlement, 2001

- "Numbered Treaty Overview". Canadiana.org (Formerly Canadian Institute for Historical Microreproductions). Canada in the Making. Retrieved 2009-11-16.

The Numbered Treaties—also called the Land Cession or Post-Confederation Treaties—were signed between 1871 and 1921, and granted the federal government large tracts of land throughout the Prairies, Canadian North, and Northwestern Ontario for white settlement and industrial use. The disruptive effects of these treaties can be still felt in modern times.

- "Biography – RIEL, LOUIS (1844-85) – Volume XI (1881-1890) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- "Thomas Scott". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. 1979–2016.

- "Thomas Scott". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- "Indigenous and Northern Relations - Province of Manitoba". Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- Weinstein, John. Quiet Revolution West: The Rebirth of Métis Nationalism. (Calgary: Fifth House Publishers, 2007)

- Gerhard Ens, "Métis Lands in Manitoba," Manitoba History (1983), Number 5, online

- D. N. Sprague, "The Manitoba Land Question 1870–1882," Journal of Canadian Studies 15#3 (1980).

- Barkwell, Lawrence. The Metis homeland: its settlements and communities. Winnipeg, Manitoba: Louis Riel Institute, 2016. ISBN 978-1-927531129.

- "The Métis" (rtf). Canada in the Making. 2005. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- "Metis Settlement General Council – Our Land. Our Culture. Our Future". metissettlements.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- "Métis Settlements General Council". Archived from the original on 2017-08-03. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- "Office of the Federal Interlocutor for Métis and Non-Status Indians (Mandate, Roles and Responsibilities)". Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-01-28. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- "1885 Northwest Resistance". indigenouspeoplesatlasofcanada.ca.

- "Founding Meeting of the American Council of Indigenous Peoples - Métis National Council". metisnation.ca. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- National Council(Canada), and Michelle M. Mann. First Nations, Métis and Inuit Children and Youth Time to Act. National Council of Welfare reports, v. #127. Ottawa: National Council of Welfare, 2007. ISBN 978-0-662-46640-6

- "Métis National Council Online". MÉTIS NATIONAL COUNCIL.

- "BC Métis Federation". bcmetis.com. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- "Who We Are". Canadianmetis.com. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- The Ontario Métis Aboriginal Association – Woodland Métis

- "OMAA names MNO in legal action against governments". Ammsa.com. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- "C28533". Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- "Nation Metis Québec - Accueil". nationmetisquebec.ca. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

-

- Barkwell, Lawrence J. Michif Language Resources: An Annotated Bibliography. Winnipeg, Louis Riel Institute, 2002. See also www.metismuseum.com

- "Fast Facts on Métis". Métis Culture & Heritage Resource Centre. Archived from the original on 2010-01-10. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- "The Michif language". Metis Culture & Heritage Resource Centre. Archived from the original on 2009-05-17. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- Barkwell, Lawrence J., Leah Dorion, and Audreen Hourie. Métis Legacy: Michif Culture, Heritage, and Folkways. Métis Legacy Series, v. 2. Saskatoon: Gabriel Dumont Institute, 2006. ISBN 0-920915-80-9

- Eleanor M. Blaine. "Bungi, Red River dialect". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- "The Métis flag". Gabriel Dumont Institute (Métis Culture & Heritage Resource Centre). Archived from the original on 2009-03-04. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- E. Foster, "The Métis: The People and the Term" (1978) 3 Prairie Forum 79, at 86–87.107

- "Métis". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

Jennifer S. H. Brown, Strangers in Blood: Fur Trade Company Families in Indian Country, 1980; People of Myth, People of History: A Look at Recent Writings on the Metis, in Acadiensis 17, 1, fall 1987; J. Peterson and Jennifer S.H. Brown, eds, New Peoples: Being and Becoming Métis in North America, 1985

- Paul L.A.H. Chartrand & John Giokas, "Defining 'the Métis People': The Hard Case of Canadian Aboriginal Law" in Paul L. A. H. Chartrand, ed., Who Are Canada's Aboriginal Peoples?: Recognition, Definition, and Jurisdiction, (Saskatoon: Purich, 2002) 268 at 294

- Daniels v. Canada (Indian Affairs and Northern Development) 2016 SCC 12, [2016] 1 SCR 99

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics. "Aboriginal Population Profile, 2016 Census - Canada [Country]". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls

- Peterson, Jacqueline; Brown, Jennifer S. H. (2001). The New Peoples: Being and Becoming Métis in North America. Winnipeg, Manitoba: University of Manitoba Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-87351-408-8.

- Peterson and Brown, The New Peoples, p. 44-45

- Wallace Gesner, "Habitants, Half-Breeds and Homeless Children: Transformations in Metis and Yankee-Yorker Relations in Early Michigan," in Michigan Historical Review Vol. 24, issue 1 (Jan. 1998) p. 23-47

- Kerry A. Trask, "Settlement in a Half-Savage Land: Life and Loss in the Métis Community of La Baye," Michigan Historical Review Vol. 15, no. 1 (Spring 1989) p. 1

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-01. Retrieved 2015-05-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)