Longfellow House–Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site

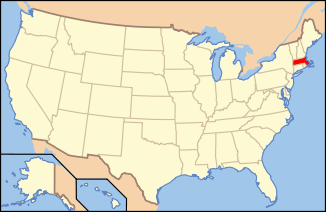

The Longfellow House–Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site (also known as the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House and, until December 2010, Longfellow National Historic Site) is a historic site located at 105 Brattle Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was the home of noted American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow for almost 50 years, and it had previously served as the headquarters of General George Washington (1775–76).

| Longfellow House–Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site | |

|---|---|

The Longfellow House | |

| |

| Location | Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA |

| Coordinates | 42°22′36″N 71°07′35″W |

| Area | 2 acres (0.81 ha) |

| Established | October 9, 1972 |

| Visitors | 50,784[1] (in 2015[1]) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site |

The house was built in 1759 for John Vassall, who fled the Cambridge area at the beginning of the American Revolutionary War because of his loyalty to the king of England. George Washington occupied it as his headquarters beginning on July 16, 1775, and it served as his base of operations during the Siege of Boston until he moved out on April 4, 1776. Andrew Craigie, Washington's Apothecary General, was the next person to own the home for a significant period of time. He purchased the house in 1791 and instigated its only major addition. Craigie's financial situation at the time of his death in 1819 forced his widow Elizabeth to take in boarders, and one of those borders was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He became its owner in 1843 when his father-in-law Nathan Appleton purchased it as a wedding gift. He lived in the home until his death in 1882.

The last family to live in the home was the Longfellow family, who established the Longfellow Trust in 1913 for its preservation. In 1972, the home and all of its furnishings were donated to the National Park Service, and it is open to the public seasonally. It presents an example of mid-Georgian architecture style.

History

Early history

The original house was built in 1759 for Loyalist John Vassall[2] who inherited the land along what was called the King's Highway in Cambridge when he was 21. He demolished the structure that had stood there and built a new mansion,[3] and the home became his summer residence with his wife Elizabeth (née Oliver) and children until 1774. His wife's brother was Thomas Oliver, the royal lieutenant governor of Massachusetts[3] who moved to Cambridge in 1766 and built the Elmwood mansion.[4] Vassall's house and all his other properties were confiscated by Patriots in September 1774 on the eve of the American Revolutionary War because he was accused of being loyal to the King.[5] He fled to Boston, and later exiled to England where he died in 1792.[6]

The home was used as a temporary hospital in the days after the Battles of Lexington and Concord.[3] Colonel John Glover and the Marblehead, Massachusetts Regiment occupied the house as their temporary barracks in June 1775.[7] General George Washington, Commander-in-Chief of the newly formed Continental Army, initially used the Benjamin Wadsworth House at Harvard College as his headquarters,[8] but he decided that he needed more space for his staff;[9] he moved into the Vassall House on July 16, 1775 and used it as his headquarters and home until he departed on April 4, 1776. During the Siege of Boston, he found the view of the Charles River from the house particularly useful.[10] The home was shared with several aides-de-camp, including colonel Robert H. Harrison.[11] Washington was visited at the house by John Adams and Abigail Adams, Benedict Arnold, Henry Knox, and Nathanael Greene.[10] In his study, he also confronted Dr. Benjamin Church with evidence that he was a spy.[12] It was in this house that Washington received a poem written by Phillis Wheatley, the first published African-American poet. "If you should ever come to Cambridge", he wrote to her, "I shall be happy to see a person so favored by the Muses".[13]

Martha Washington joined her husband in December 1775 and stayed until March 1776.[6] She brought with her Washington's nephew George Lewis as well as her son John Parke Custis and his wife Eleanor Calvert.[11] On Twelfth Night in January 1776, the couple celebrated their wedding anniversary in the home.[7] Mrs. Washington reported to a friend that "some days we have [heard] a number of cannon and shells from Boston and Bunkers Hill".[10] She used the front parlor as her personal reception room, still furnished with the English-made furniture left behind by the Vassalls.[14] The Washingtons also had several servants, including a tailor named Giles Alexander, and several slaves including "Billy" Lee.[11] They also entertained very often. Surviving household accounts show that the family purchased large quantities of beef, lamb, wild ducks, geese, fresh fish, plums, peaches, barrels of cider, gallons of brandy and rum,[15] and 217 bottles of Madeira wine purchased in a two-week period.[16]

Washington left the house in April 1776.[17] Nathaniel Tracy had made a great fortune as one of the earliest and most successful privateers under Washington, and he owned the house from 1781 to 1786. He then went bankrupt and sold it to Thomas Russell, a wealthy Boston merchant who occupied it until 1791.

Craigie family and boarders

Andrew Craigie had been the first Apothecary General of the American army, and bought the house in 1791.[18] He hosted Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn in the ballroom; Prince Edward was the father of Queen Victoria.[19] Craigie married Elizabeth while living in the house; she was the daughter of a Nantucket clergyman and only 22 years old, 17 years younger than he.[7]

Craigie overspent trying to restore the home,[17] and left Elizabeth in great debt when he died in 1819. She took in boarders to support herself,[20] most often people connected to nearby Harvard University.[16] Short-term residents of the home included Jared Sparks, Edward Everett, and Joseph Emerson Worcester.[21] Sparks moved into the home in April 1833 while he was preparing a biography of Washington based on original documents. He recorded in his journal: "It is a singular circumstance that, while I am engaged in preparing for the press the letters of General Washington which he wrote at Cambridge after taking command of the American army, I should occupy the same rooms that he did at that time."[22] Another lodger was Sarah Lowell, an aunt of James Russell Lowell.[23]

Longfellow moved to Cambridge to take a job at Harvard College as Smith Professor of Modern Languages and of Belles Lettres,[24] and rented rooms on the second floor of the home beginning in the summer of 1837.[19] Elizabeth Craigie initially refused to rent to him because she thought that he was a student at Harvard, but Longfellow convinced her that he was a professor there, as well as the author of Outre-Mer, the very book that she was reading.[25]

Longfellow's new landlady had earned a reputation for being eccentric[20] and often wore a turban. In the 1840s, Longfellow wrote about an incident where canker-worms were devastating the elm trees on the property. Elizabeth Craigie "would sit by the open window and let them crawl over her white turban. She refused to have the trees protected against them & said, Why, sir, they have as good a right to live as we—they are our fellow worms".[17] He wrote to his father in August 1837, "The new rooms are above all praise, only they do want painting."[26] The rooms that he rented were the same ones once used personally by George Washington while it was his headquarters,[10] and he wrote to his friend George Washington Greene: "I live in a great house which looks like an Italian villa: have two large rooms opening into each other. They were once Gen. Washington's chambers".[17]

The first major works that Longfellow composed in the home were Hyperion, a prose romance likely inspired by his pursuit for the affections of Frances Appleton, and Voices of the Night, a poetry collection which included "A Psalm of Life".[20] Edward Wagenknecht notes that it was these early years at the Craigie House which marked "the real beginning of Longfellow's literary career".[27] His landlady, Elizabeth Craigie, died in 1841.[28]

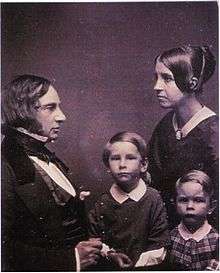

Longfellow family

Joseph Emerson Worcester leased the property from Elizabeth Craigie's heirs after her death, and he rented the eastern half to Longfellow.[29] Nathan Appleton purchased the house in 1843 for $10,000; Longfellow married his daughter Frances, so Appleton gave him the house as a wedding gift.[30][29] Longfellow's friend George Washington Greene reminded them "how noble an inheritance this is — where Washington dwelt in every room".[31] Longfellow was proud of the connection to Washington and purchased a bust of him in 1844, a copy of the sculpture by Jean-Antoine Houdon.[32]

Longfellow lived in the house for the next four decades, producing many of his most famous poems including "Paul Revere's Ride" and "The Village Blacksmith",[33] as well as longer works such as Evangeline, The Song of Hiawatha, and The Courtship of Miles Standish.[28] He published 11 poetry collections, two novels, three epic poems, and several plays while living in this house, as well as a translation of Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy.[34] He and his wife most often referred to it as "Craigie House" or "Craigie Castle".[35]

Longfellow oversaw the creation of a formal garden, and his wife oversaw decorating the interior.[36] She purchased several items from Tiffany & Co. in New York, as well as $350 worth of carpets.[37] They installed central heating in 1850 and gaslight in 1853.[36] The family hosted famous artists, writers, politicians, and other luminaries who were attracted to Longfellow's hospitality and fame. Specific visitors included Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray, singer Jenny Lind, and actress Fanny Kemble.[38] Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil also visited the house privately and requested the company of Longfellow, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., and James Russell Lowell.[39] The couple also raised their three daughters and two sons in the home.[19] They stayed in the home until their respective deaths but spent their summers after 1850 in Nahant, Massachusetts.[40]

Longfellow often wrote in his first-floor study, formerly Washington's office, surrounded by portraits of his friends, including charcoal portraits by Eastman Johnson of Charles Sumner, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Cornelius Conway Felton. He would write at the center table, at the desk, or in the armchair by the fire.[38] His second wife Fanny died in the home in July 1861 after her dress accidentally caught fire. He attempted to quell the flames, managing to keep her face from burning,[41] but he was burned on his own face and was scarred badly enough that he began growing a beard to hide it.[42]

Preservation and current use

Longfellow died in 1882 and his daughter Alice Longfellow was the last of his children to live in the home. In 1913, the surviving Longfellow children established the Longfellow House Trust to preserve the home as well as its view to the Charles River.[43] Their intention was to preserve the home as a memorial to Longfellow and Washington and to showcase the property as a "prime example of Georgian architecture".

In 1962, the trust successfully lobbied for the house to become a national historic landmark. In 1972, the Trust donated the property to the National Park Service and it became the Longfellow National Historic Site and open to the public as a house museum.[16] On display are many of the original nineteenth century furnishings, artwork, over 10,000 books owned by Longfellow, and the dining table around which many important visitors gathered.[44] Everything on display was owned by the Longfellow family. The site was renamed to Longfellow House–Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site on December 22, 2010, to ensure that the connection to Washington was not lost in the memory of the general public.[45]

The site also possesses some 750,000 original documents relevant to the former occupants of the home.[46] These archives are open to scholarly research by appointment.

Across the street from the Longfellow House–Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site is the municipal park known as Longfellow Park.[43] In the middle sits a memorial by sculptor Daniel Chester French dedicated in 1914. In addition to a bust of the poet, a carved bas-relief by Henry Bacon depicts the famous characters Miles Standish, Sandalphon, the village blacksmith, the Spanish student, Evangeline, and Hiawatha.[44] The monument is similar to one French designed for the street that leads to Sunnyside, the former home of Washington Irving.[47]

Architecture and landscape

The original 1759 house was built in the Georgian architectural style.[2] The pair of large pilasters that frame the central entry portal created two side wings, also framed by large pilasters. The house is influenced by the English architect James Gibbs, who published his "Book of Architecture" in 1728. Gibbs demonstrated a melding of the English Baroque style with the new Palladian movement.[48] This facade configuration effectively expressed the rising prosperity and status of John Vassall's family background.[3] In 1791, Andrew Craigie added the two side porches and the two-story back ell and also expanded the library into a twenty by thirty foot ballroom with its own entrance.[18] During the Longfellow family's time in the home, very few structural changes were made. As Frances Longfellow wrote, "we are full of plans & projects with no desire, however, to change a feature of the old countenance which Washington has rendered sacred".[16]

The Longfellow House–Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site is noted for its garden on the northeast end of the property. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow oversaw the creation of the original garden, shaped as a lyre, shortly after his wedding.[36] In 1845, he began refurbishing the garden in earnest and imported trees from England with help from Asa Gray. These trees included "a number of evergreens, among them a cedar of Lebanon and pines from the Himalayas, Norway, Switzerland and Oregon".[49] The lyre shape proved impractical and a new design was made with the help of a landscape architect named Richard Dolben in 1847. The new design was a square surrounding a circle that was cut into four tear-shaped garden beds outlined by trimmed boxwood. Mrs. Longfellow referred to the shape as a "Persian rug".[50]

After her father's death in 1882, Alice Longfellow commissioned two of America's first female landscape architects, Martha Brookes Hutcheson and Ellen Biddle Shipman, to redesign the formal garden in the Colonial Revival style. The garden was recently restored by an organization called Friends of the Longfellow House, which completed the final stage of its reconstruction, the historic pergola, in 2008.

Replicas

For a time, Longfellow's home was one of the most photographed and most recognizable homes in the United States. In the early twentieth century Sears, Roebuck and Company sold scaled-down blueprints of the home so that anyone could build their own version of Longfellow's home.[51] Several replicas of Longfellow's home appear throughout the United States. One replica, simply called Longfellow House, still exists in Minneapolis. Originally built by businessman Robert "Fish" Jones, it currently serves as an information center for the Minneapolis Park System and is on the Grand Rounds Scenic Byway. A full-scale replica of the house was built in Great Barrington, Massachusetts at the turn of the 20th century. This building is the only remaining full-scale replica of Longfellow's original home maintaining all the original historical character. There is also a replica in Aberdeen, South Dakota on Main St.

See also

References

- "National Park Service Visitor Use Statistics". National Park Service Visitor Use Statistics. National Park Service. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- Calhoun, Charles C. Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004: 124. ISBN 0-8070-7026-2.

- Howard, Hugh. Houses of the Founding Fathers. New York: Artisan, 2007: 84. ISBN 978-1-57965-275-3

- "NRHP Nomination for Elmwood". National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- Stark, James Henry. The Loyalists of Massachusetts and the Other Side of the American Revolution.

- Levine, Miriam. A Guide to Writers' Homes in New England. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Apple-wood Press, 1984: 124. ISBN 0-918222-51-6

- Harris, John. Historic Walks in Cambridge. Chester, Connecticut: The Globe Pequot Press, 1986: 208. ISBN 0-87106-899-0

- Benjamin Wadsworth House Archived 2014-04-16 at the Wayback Machine from Historic Buildings of Massachusetts.

- McCullough, David. 1776. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005: 41. ISBN 978-0-7432-2672-1

- Calhoun, Charles C. Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004: 125. ISBN 0-8070-7026-2.

- Howard, Hugh. Houses of the Founding Fathers. New York: Artisan, 2007: 85. ISBN 978-1-57965-275-3

- Howard, Hugh. Houses of the Founding Fathers. New York: Artisan, 2007: 87. ISBN 978-1-57965-275-3

- Howard, Hugh. Houses of the Founding Fathers. New York: Artisan, 2007: 91. ISBN 978-1-57965-275-3

- Howard, Hugh. Houses of the Founding Fathers. New York: Artisan, 2007: 86. ISBN 978-1-57965-275-3

- McCullough, David. 1776. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005: 42. ISBN 978-0-7432-2672-1

- Howard, Hugh. Houses of the Founding Fathers. New York: Artisan, 2007: 89. ISBN 978-1-57965-275-3

- Calhoun, Charles C. Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004: 126. ISBN 0-8070-7026-2.

- Levine, Miriam. A Guide to Writers' Homes in New England. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Apple-wood Press, 1984: 124–125. ISBN 0-918222-51-6

- Harris, John. Historic Walks in Cambridge. Chester, Connecticut: The Globe Pequot Press, 1986: 209. ISBN 0-87106-899-0

- Wagenknecht, Edward. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: Portrait of an American Humanist. New York: Oxford University Press, 1966: 7

- Brooks, Van Wyck. The Flowering of New England. New York: E. P. Dutton and Company, Inc., 1952: 153

- "The George Washington Papers: Provenance and Publication History" at the Library of Congress

- Hansen, Harry. Longfellow's New England. New York: Hastings House, 1972: 48. ISBN 0-8038-4279-1

- Williams, Cecil B. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1964: 72–73

- Wagenknecht, Edward. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: Portrait of an American Humanist. New York: Oxford University Press, 1966: 6–7

- Hansen, Harry. Longfellow's New England. New York: Hastings House, 1972: 35. ISBN 0-8038-4279-1

- Wagenknecht, Edward. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: Portrait of an American Humanist. New York: Oxford University Press, 1966: 8

- Ehrlich, Eugene and Gorton Carruth. The Oxford Illustrated Literary Guide to the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982: 39. ISBN 0-19-503186-5

- Calhoun, Charles C. Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004: 167. ISBN 0-8070-7026-2.

- Wilson, Susan. Literary Trail of Greater Boston. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000: 109. ISBN 0-618-05013-2

- Tharp, Louise Hall. The Appletons of Beacon Hill. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1973: 239.

- Howard, Hugh. Houses of the Founding Fathers. New York: Artisan, 2007: 90. ISBN 978-1-57965-275-3

- Haas, Irvin. Historic Homes of American Authors. Washington, DC: The Preservation Press, 1991: 93. ISBN 0-89133-180-8.

- Irmscher, Christoph. Longfellow Redux. University of Illinois, 2008: 8. ISBN 978-0-252-03063-5.

- Tharp, Louise Hall. The Appletons of Beacon Hill. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1973: 245.

- Levine, Miriam. A Guide to Writers' Homes in New England. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Apple-wood Press, 1984: 125. ISBN 0-918222-51-6

- Tharp, Louise Hall. The Appletons of Beacon Hill. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1973: 242.

- Levine, Miriam. A Guide to Writers' Homes in New England. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Apple-wood Press, 1984: 126. ISBN 0-918222-51-6

- Arvin, Newton. Longfellow: His Life and Work. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1963: 145.

- Calhoun, Charles C. Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004: 170. ISBN 0-8070-7026-2.

- Levine, Miriam. A Guide to Writers' Homes in New England. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Apple-wood Press, 1984: 127. ISBN 0-918222-51-6

- Wilson, Susan. Literary Trail of Greater Boston. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000: 110. ISBN 0-618-05013-2

- Harris, John. Historic Walks in Cambridge. Chester, Connecticut: The Globe Pequot Press, 1986: 210. ISBN 0-87106-899-0

- Wilson, Susan. Literary Trail of Greater Boston. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000: 111. ISBN 0-618-05013-2

- "Longfellow House-Washington Headquarters National Historic Site" (PDF). Longfellow House Bulletin. National Park Service (Volume 15, No. 1). June 2011.

- Longfellow National Historic Site Archives, accessed July 10, 2008

- Hansen, Harry. Longfellow's New England. New York: Hastings House, 1972: 143. ISBN 0-8038-4279-1

- Gelernter, Mark (1999). A History of American Architecture. Manchester University Press. p. 90. ISBN 0719047269.

- Leighton, Ann. American Gardens of the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1987: 223. ISBN 0-87023-533-8.

- Leighton, Ann. American Gardens of the Nineteenth Century. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1987: 224. ISBN 0-87023-533-8.

- Calhoun, Charles C. Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004: 245. ISBN 0-8070-7026-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Longfellow National Historic Site. |