Languages of the Soviet Union

The languages of the Soviet Union are hundreds of different languages and dialects from several different language groups.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Traditions |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

|

Art |

| Literature |

|

Music and performing arts |

| Sport |

|

Monuments |

|

Symbols

|

|

In 1922, it was decreed that all nationalities in the Soviet Union had the right to education in their own language. The new orthography used the Cyrillic, Latin, or Arabic alphabet, depending on geography and culture. After 1937, all languages that had received new alphabets after 1917 began using the Cyrillic alphabet. This way, it would be easier for linguistic minorities to learn to write both Russian and their native language. In 1960, the school educational laws were changed and teaching became more dominated by Russian. Moreover, the Armenian and Georgian, as well as the Baltic Soviet Socialist Republics were the only Soviet republics to maintain their writing systems (Armenian, Georgian and Latin alphabets respectively).

In 1975, Brezhnev said "under developed socialism, when the economies in our country have melted together in a coherent economic complex; when there is a new historical concept—the Soviet people—it is an objective growth in the Russian language's role as the language of international communications when one builds Communism, in the education of the new man! Together with one's own mother tongue one will speak fluent Russian, which the Soviet people have voluntarily accepted as a common historical heritage and contributes to a further stabilization of the political, economic and spiritual unity of the Soviet people."

Distribution and status

East Slavic languages (Russian, Belarusian and Ukrainian) dominated in the European part of the Soviet Union, the Baltic languages Lithuanian and Latvian, and the Finnic language Estonian were used next to Russian in the Baltic region, while Moldovan (the only Romance language in the union) was used in the southwest region. In the Caucasus alongside Russian there were Armenian, Azeri and Georgian. In the Russian far north, there were several minority groups who spoke different Uralic languages; most of the languages in Central Asia were Turkic with the exception of Tajik, which is an Iranian language.

The USSR was a multilingual state, with over 123 languages spoken natively. Discrimination on the basis of language was illegal under the Soviet Constitution, though status of its languages differed.

Although the USSR did not have de jure an official language over most of its history, until 1990,[1] and Russian was merely defined as the language of interethnic communication (Russian: язык межнационального общения), it assumed de facto the role of official language.[2] For its role and influence in the USSR, see Russification.

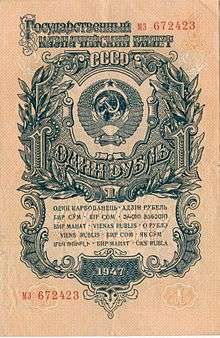

On a second level were the languages of the other 14 Union Republics. In line with their de jure status in a federal state, they had a small formal role at the Union level (being e.g. present in the Coat of arms of the USSR and its banknotes) and as the main language of its republic. Their effective weight, however, varied with the republic (from strong in places like in Armenia to weak in places like in Byelorussia), or even inside it.

Of these fourteen languages, two are often considered varieties of other languages: Tajik of Persian, and Moldovan of Romanian. Strongly promoted use of Cyrillic in many republics however, combined with lack of contact, led to the separate development of the literary languages. Some of the former Soviet republics, now independent states, continue to use the Cyrillic alphabet at present (such as Kyrgyzstan), while others have opted to use the Latin alphabet instead (such as Turkmenistan and Moldova – although the unrecognized Transnistria officially uses the Cyrillic alphabet).

The Autonomous republics of the Soviet Union and other subdivision of the USSR lacked even this de jure autonomy, and their languages had virtually no presence at the national level (and often, not even in the urban areas of the republic itself). They were, however, present in education (although often only at lower grades).

Some smaller languages with very dwindling small communities, like Livonian, were neglected, and weren't present either in education or in publishing.

Several languages of non-titular nations, like German, Korean or Polish, although having sizable communities in the USSR, and in some cases being present in education and in publishing, were not considered to be Soviet languages. On the other hand, Finnish, although not generally considered a language of the USSR, was an official language of the Karelia and its predecessor as a Soviet republic. Also Yiddish and Romany were considered Soviet languages.

Distribution of Russian in 1989

| Ethnic group | Total (in thousands) | Speakers (in thousands) | Percentage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | L2 | Total | L1 | L2 | Total | ||

| Russians | 145,155 | 144,836 | 219 | 145,155 | 99.8 | 0.2 | 100 |

| Non-Russian | 140,587 | 18,743 | 68,791 | 87,533 | 13.3 | 48.9 | 62.3 |

| Ukrainians | 44,186 | 8,309 | 24,820 | 33,128 | 18.8 | 56.2 | 75.0 |

| Uzbeks | 16,698 | 120 | 3,981 | 4,100 | 0.7 | 23.8 | 24.6 |

| Belarusians | 10,036 | 2,862 | 5,487 | 8,349 | 28.5 | 54.7 | 83.2 |

| Kazakhs | 8,136 | 183 | 4,917 | 5,100 | 2.2 | 60.4 | 62.7 |

| Azerbaijanis | 6,770 | 113 | 2,325 | 2,439 | 1.7 | 34.3 | 36.0 |

| Tatars | 6,649 | 1,068 | 4,706 | 5,774 | 16.1 | 70.8 | 86.8 |

| Armenians | 4,623 | 352 | 2,178 | 2,530 | 7.6 | 47.1 | 54.7 |

| Tajiks | 4,215 | 35 | 1,166 | 1,200 | 0.8 | 27.7 | 28.5 |

| Georgians | 3,981 | 66 | 1,316 | 1,382 | 1.7 | 33.1 | 34.7 |

| Moldovans | 3,352 | 249 | 1,805 | 2,054 | 7.4 | 53.8 | 61.3 |

| Lithuanians | 3,067 | 55 | 1,163 | 1,218 | 1.8 | 37.9 | 39.7 |

| Turkmens | 2,729 | 27 | 757 | 783 | 1.0 | 27.7 | 28.7 |

| Kyrgyz | 2,529 | 15 | 890 | 905 | 0.6 | 35.2 | 35.8 |

| Germans | 2,039 | 1,035 | 918 | 1,953 | 50.8 | 45.0 | 95.8 |

| Chuvash | 1,842 | 429 | 1,199 | 1,628 | 23.3 | 65.1 | 88.4 |

| Latvians | 1,459 | 73 | 940 | 1,013 | 5.0 | 64.4 | 69.4 |

| Bashkirs | 1,449 | 162 | 1,041 | 1,203 | 11.2 | 71.8 | 83.0 |

| Jews | 1,378 | 1,194 | 140 | 1,334 | 86.6 | 10.1 | 96.7 |

| Mordvins | 1,154 | 377 | 722 | 1,099 | 32.7 | 62.5 | 95.2 |

| Poles | 1,126 | 323 | 495 | 817 | 28.6 | 43.9 | 72.6 |

| Estonians | 1,027 | 45 | 348 | 393 | 4.4 | 33.9 | 38.2 |

| Others | 12,140 | 1,651 | 7,479 | 9,130 | 13.6 | 61.6 | 75.2 |

| Total | 285,743 | 163,898 | 68,791 | 232,689 | 57.4 | 24.1 | 81.4 |

See also

- Index of Soviet Union-related articles

- Education in the Soviet Union

- Korenizatsiya

- Russification

- Languages of Russia

- Languages of Kazakhstan

- Languages of Ukraine

References

- In early 20th century, there had been a discussion over the need to introduce Russian as the official language of Russian Empire. The dominant view among Bolsheviks at that time was that there is no need for state language. See: "Нужен ли обязательный государственный язык?" by Lenin (1914). Staying with the Lenin's view, not state language was declared in the Soviet state.

In 1990 the Russian language was declared as the official language of USSR and the constituent republics had rights to declare additional state languages within their jurisdictions. See Article 4 of the Law on Languages of Nations of USSR. Archived 2016-05-08 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian) - Bernard Comrie, The Languages of the Soviet Union, page 31, the Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1981. ISBN 0-521-23230-9

- "All-Soviet Census 1989. Population by ethnic group and language". Demoscope Weekly (in Russian).

Sources

- Bernard Comrie. The Languages of the Soviet Union. CUP 1981. ISBN 0-521-23230-9 (hb), ISBN 0-521-29877-6 (pb)

- E. Glyn Lewis. Multilingualism in the Soviet Union: Aspects of Language Policy and Its Implementation. The Hague: Mouton Publishers, 1971.

- Языки народов СССР. 1967. Москва: Наука 5т.

External links

- Soviet Language Policy in Central Asia by Mark Dickens

- "Language Policies in Present-Day Central Asia" (PDF). BIRGIT N. SCHLYTER. Stockholm University. International Journal on Multicultural Societies (IJMS)Vol. 3, No. 2, 2001 "The Human Rights of Linguistic Minorities and Language Policies".