Gronings dialect

Gronings (Dutch pronunciation: [ˈɣroːnɪŋs]; Gronings: Grunnegs or Grönnegs), is a collective name for some Friso-Saxon dialects spoken in the province of Groningen and around the Groningen border in Drenthe and Friesland. Gronings and the strongly related varieties in East Frisia have a strong East Frisian influence and take a remarkable position within West Low German. The dialect is characterized by a typical accent and vocabulary, which differ strongly from the other Low Saxon dialects.

| Gronings | |

|---|---|

| Grunnegs, Grönnegs | |

| Native to | Netherlands: Groningen, parts in the north and east of Drenthe, the east of the Frisian municipality Kollumerland en Nieuwkruisland |

| Region | Groningen |

Native speakers | 590,000 (2003)[1] |

| Official status | |

Official language in | the Netherlands |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | gos |

| Glottolog | gron1242[2] |

| |

| This article is a part of a series on |

| Dutch |

|---|

| Dutch Low Saxon dialects |

| West Low Franconian dialects |

| East Low Franconian dialects |

|

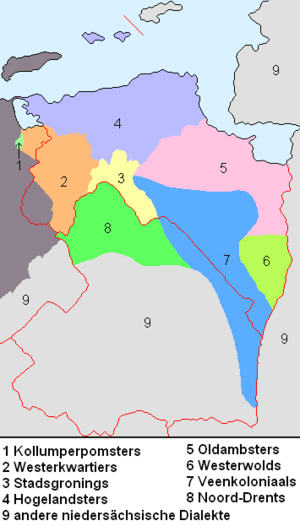

Area

The name Gronings can almost be defined geographically, as can be seen on the map below. This is especially true for the northern part of Drenthe (number 8 on that map). The Drents, spoken in the north of the province of Drenthe (Noordenveld) is somewhat related with the Groninger language, but the core linguistics is Drents. For the dialects in the southeast, called Veenkoloniaals, it is a bit different on both sides of the Groningen-Drenthe border, as the dialect spoken there is much more related to Gronings. In the Frisian municipality of Kollumerland en Nieuwkruisland, the western dialect called Westerkwartiers is also spoken, as well as a separate Groningen dialect called Kollumerpompsters. The latter is spoken in the Frisian village of Kollumerpomp and has more West Frisian influences, while most Groningen dialects have a strong influence from the East Frisian language.

Dialects

The Gronings language can be subdivided into 8 dialects:

| Subdivision of the Groningen dialects |

|

| Gronings dialects in the provinces of Groningen, Friesland, and Drenthe |

- Kollumerpompsters

- Westerkwartiers

- Stadjeders

- Hogelandsters

- Oldambtsters

- Westerwolds

- Veenkoloniaals

- Noord-Drents

- Other varieties of Dutch/German Low Saxon

Example

Though there are several differences between the dialects, they form a single dialect group. Most words are written the same way, but the pronunciation can differ. The examples show the pronunciation.

- Westerkertiers: t Eenege dat wie niet doun is slik uutdeeln

- Stadsgrunnegs (city): t Oinege dat wie noit doun is baaltjes oetdailn

- Hoogelaandsters: t Ainege dat wie nait dudden is slik oetdijln

- Westerwoolds: t Einege dat wie nich dun is slikkerij uutdeiln

- Veenkelonioals: t Ainege wat wie nait dudden is slikke uutduiln

- East Frisian Low Saxon: Dat eenzige, dat wi neet doon is Slickeree utdelen.

- North German Low Saxon: Dat eenzige, dat wi nich doot, (dat) is Snabbelkraam uutdeeln.

- Standard Dutch: Het enige wat we niet doen is snoep uitdelen.

- Standard German: Das einzige, was wir nicht machen [="was wir nicht tun"], ist Süßigkeiten austeilen.

- Scots: The anerly thing we dinnae dae is gie oot snashters.

- English: The only thing we don't do is hand out sweets.

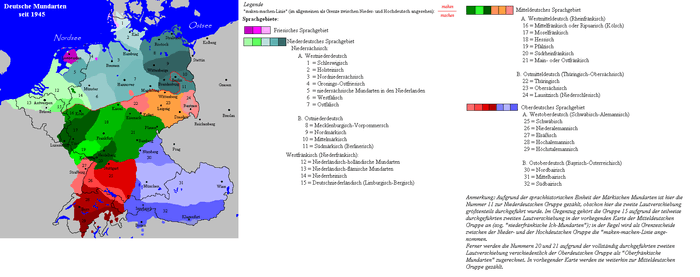

Classification

There are many uncertainties about the classification and categorization of Gronings. Some linguists see it as a variety of Low German, also called Nedersaksisch in the Netherlands. These words are actually more political than linguistic, because they unite a large group of very differing varieties. Categorizing Gronings as Low German could be considered correct, but there is controversy surrounding the existence of the linguistic unity of Low German.

Others, especially German linguists, see Gronings-East Frisian as a separate group of German dialects. The East Frisian influence, the sounds ou, ai and ui and the typical accent are crucial here. Gronings-East Frisian would be categorized as Friso-Saxon dialects instead of Low German. Other linguists categorize all Gronings-East Frisian dialects as North Low German. In that case, all the other Low German varieties in the Netherlands are categorized as Westphalian.

Dutch linguists in particular classify Gronings as Dutch Low Saxon, in Germany also called Westplatt. In this case the Dutch influence is crucial, while the dialects on the other side of the national border are strongly influenced by High German languages. These influences concern especially the vocabulary, like the Dutch word "voorbeeld" (example) which is "veurbeeld" in Gronings while the East Frisian dialects use "biespööl", which is related to the High German word "beispiel". In this case there is no separation between Groningen-East Frisian (or North Low Saxon) and Westphalian, but rather a difference between Groningen and East Frisian. The national border would equal the linguistic border.

Origin

The Gronings dialects are a kind of mix between two languages: Old Frisian (East Frisian) and Middle Low German. East Frisian was spoken in the Ommelanden (surrounding lands of the city of Groningen), while the city, the surrounding rural area called Gorecht and the eastern lordship of Westerwolde were Low Saxon. When the city of Groningen developed an important position in the Ommelanden, a switch from East Frisian to Saxon occurred, although it was not a complete switch because there are many East Frisian influences in the "new" Groningen language. Many East Frisian words and grammatic features are still in use today. In less than one century, the same process also started in East Frisia, from the city of Emden, which was influenced by the Hanseatic League. This explains the strong relation between both varieties.

In the second half of the 16th century Gronings started to evolve towards Middle Dutch because of the strong influence of the new standard language. But because of the political, geographical and cultural isolation of Groningen, a strong provincialism in the first half of the 19th century caused Gronings to develop itself in a significant way. The sounds that are used today were formed in this period.

Usage

Daily life

Today, according to an investigation among the listeners to the regional broadcasting station (Radio Noord), approximately 65% of them can speak and write Gronings. Perhaps If the larger cities and villages of Groningen, Hoogezand-Sappemeer, Veendam, Stadskanaal, Delfzijl and Winschoten are excluded from this count, the percentage would rise to about 80%. Of course, this is not a representative picture of the linguistic capacity of the inhabitants of Groningen province. Most of the older people use Gronings as their main language. Until the second half of the 20th century, Gronings was more important in Groningen than Dutch. Younger people also speak the language, however in a regiolectical mixed way, because many pure Gronings words are lost. The youngest generation passed to Dutch. Since the second half of the 20th century, the usage of the language is declining. Because of globalization, other languages like Dutch and English are becoming more important. Parents today chose to raise their children in the Dutch language.

Media

In the media Gronings is used frequently. For example, on the local radio station Radio Noord, Gronings is used by the presenters and listeners. On local television Gronings is used less, but the weather forecast is always presented in Gronings. The news is always presented in Dutch, since not all viewers understand Gronings. In the second half of 2007, the local television broadcast a series in Gronings called Boven Wotter. Another program that is in and about Gronings is Grunnegers, which is actually some kind of education in Gronings.

Examples of Gronings magazines are Toal en Taiken (language and signs) and Krödde, which actually means cannabis.

There are many Gronings dictionaries as well. The first official dictionary was the "Nieuw Groninger Woordenboek" and was put together by Kornelis ter Laan. This dictionary and the writing system used in the book became the basics of each dictionary and writing system ever since.

More recent is "Zakwoordenboek Gronings - Nederlands / Nederlands - Gronings" by Siemon Reker, which is a little less specific. K. G. Pieterman wrote a dictionary of Gronings alliterations which is titled Gezondhaid en Groutnis (sanity and greetings).

Education and culture

Although Gronings, as part of Low Saxon, is an official language, it is not a mandatory subject in schools. Still, many primary schools in Groningen choose to give attention to the regional language. This attention varies from inviting storytellers to teaching about the language. In secondary schools Gronings does not receive much attention.

At the University of Groningen it is possible to study the language. In October 2007 Gronings became an official study within the faculty of letteren (language and literature). The new professor, Siemon Reker, had already undergone many studies in the language and is famous for his dictionary.

Another possible way to learn Gronings is taking classes. In the last few years the trend of people taking courses has risen. More and more people, also people from outside who come to live in the area in which Gronings is spoken, are interested in the language and are willing to take courses. There are two types of courses. The first one is understanding and the second one is understanding and speaking.

Every year around March Het Huis van de Groninger Cultuur (English: House of the Groningen Culture) organises a writing contest in every municipality in Groningen.[3] Everyone can participate and send in a poem or some prose. The winners of the different ages succeed to the provincial round.

Music

Well known Groningen musical artists are Wia Buze, Alje van Bolhuis, Alex Vissering, Eltje Doddema, Pé Daalemmer & Rooie Rinus, Burdy, Hail Gewoon and Ede Staal (†). Every year the supply of successful artists in regional languages in the Netherlands is rising.

Frisian substratum

Some linguists classify Gronings to North Low Saxon, to which also East Frisian belongs. Both related dialects are characterized by an East Frisian influence. Hence other linguists classify Gronings-East Frisian as a separate group of Northwest Low Saxon or Friso-Saxon dialects. The most important similarities are grammar features and the vocabulary. The most important differences are the writing system and the loanwords. The East Frisian writing system is based on High German while Gronings uses many Dutch features. For example, the word for “ice skate” is in Gronings “scheuvel” and in East Frisian “Schöfel”, while the pronunciation is almost alike. Here are a few examples of words compared to West Frisian, East Frisian Low Saxon, German, Dutch and English.

| West Frisian | East Frisian | Gronings | German | Dutch | English |

| Reed | Schöfel | Scheuvel | Schlittschuh | Schaats | Ice skate |

| Lyts | Lüttje | Lutje | Klein | Klein or Luttel | Little |

| Foarbyld | Bispööl | Veurbeeld | Beispiel | Voorbeeld | Example |

| Bloet | Bloot [blout] | Bloud | Blut | Bloed | Blood |

The East Frisian combination -oo (for example in Bloot = blood) is pronounced like -ow in the English word “now”([blowt]; Gronings: blowd). In some parts of the Rheiderland they say blyowt, which is a leftover of Frisian in this area. The East Frisian combination -aa (for example in quaad) is pronounced like –a in the British English word “water”. In Gronings this sound is written like –oa. The word water would be written like “woatah” in Gronings. The pronunciation of the word “quaad” is similar to the Gronings word “kwoad”, which means “angry”. The East Frisian combination -ee and -eei (for example in neet) are pronounced like the –y in the English word “fly” ([nyt]; Gronings: nyt)*.

Linguistic distance from Standard Dutch

After Limburgish, Gronings is the dialect with the farthest distance from Standard Dutch. Reasons for this are vocabulary and pronunciation. The Gronings vocabulary is quite different from Dutch, for example:

- Gronings: Doe hest n hail ìnde luu dij scheuvellopen kinnen, pronounced: [du‿ɛst‿n̩ ɦaɪ̯l‿ɪndə ly daɪ̯‿sχøːvəloːʔm̩ kɪnː]

- Dutch: Jij hebt heel veel werknemers die kunnen schaatsen, pronounced: [jɛi ɦɛpt ɦeːl veːl ʋɛrkneːmərs di kɵnə(n) sxaːtsə(n)]

- English: You have a lot of employees who can ice skate

The pronunciation differs from the writing system. The -en ending of many words is pronounced like (ə or ən) in most varieties of Dutch. In Gronings and many other Low Saxon dialects these words are pronounced with a glottal stop, thus making the words ending in [ʔŋ], [ʔn] or [ʔm]. The Groningen people speak quite fast compared to the Dutch people, with the result that a lot of words are pronounced together as one word.

Gronings is also a dialect with many unique expressions. One third of the language consists of these expressions. In the example sentence n hail ìnde is an example of those expressions. Many of these are given in the 'Nieuwe Groninger Woordenboek' by K. ter Laan published in 1977, (1280pp).

Because of this far distance from Standard Dutch and the official status of the neighbouring West Frisian, Gronings is considered as a separate language by some of its native speakers, while linguists consider it part of Dutch Low Saxon.

|

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Dorsal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | k | |

| voiced | b | d | (ɡ) | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | χ | |

| voiced | v | z | ɣ | ɦ | |

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||

| Trill | r | ||||

| Approximant | ʋ ~ w | l | j | ||

- /ʋ/ occurring before and after rounded vowels is pronounced as a labio-velar approximant /w/.

- /ɡ/ only occurs in word-medial position, in word-initial position, it is always pronounced as /ɣ/.

- /n/ occurring in word-final positions after a non-nasal consonant, can either be realized as syllabic sounds [m̩ n̩ ŋ̍ ɴ̩] or pre-glottal as [ʔm, ʔn, ʔŋ]. A labial nasal sound only occurring after a labial consonant, and a velar nasal sound after a velar consonant. The rest of the positions of /n/, are realized as either [n̩] or [ʔn].

- Other word-final consonants occur as syllabic, as a variant of a schwa sound /ə/ before a consonant (e.g. [əl] ~ [l̩]).[4]

Example

Lord’s Prayer

- Os Voader in Hemel, (litt. Our Father in Heaven)

- dat Joen Noam haailegd worden zel, (litt. May Thy name be hallowed)

- dat Joen Keunenkriek kommen mag, (litt. May Thy kingdom come)

- dat Joen wil doan wordt (litt. May Thy will be done)

- op Eerd net as in hemel. (litt. On earth, like in heaven)

- t Stoet doar wie verlet om hebben (litt. The bread we need so badly)

- geef os dat vandoag, (litt. give it to us today)

- en reken os nait tou wat wie verkeerd doun, (litt. And do not blame us for the things we do wrong)

- net zo as wie vergeven elk dij os wat aandut. (litt. As we forgive those who trespass against us)

- En breng os nait in verlaaiden, (litt. And lead us not into temptation)

- mor wil van verlaaider ons verlözzen. (litt. But deliver us from the tempter)

- Den Joe binnen t Keunenkriek, (litt. Because Thou art the kingdom)

- de Kracht en de Heerlekhaid. (litt. the Power and the Glory)

- Veur in aiweghaid. (litt. For eternity)

- Amen

Vocabulary

The Gronings vocabulary is strongly related to East Frisian Low Saxon, Saterfrisian and West Frisian. However, today the pure Gronings vocabulary is in decline. More and more Gronings words are being replaced by “Groningized” Dutch words. For example, the word “stevel” (boot, German “Stiefel”) is sometimes replaced by the word “leers” (Dutch “laars”). Although most people do know the pure words, they are less and less used, for example because people think others will not understand them or because they are too long and the Dutch word is much easier. An example of the latter is the word for sock, which is “Hozevörrel” in Gronings. The Dutch word “sok” is much easier, so it is more often used than hozevörrel.

Some often used Gronings words are listed below;

| Gronings | Dutch | English |

|---|---|---|

| Aingoal | Voortdurend | Continuously |

| Aine | Iemand | Someone |

| Akkenail | Dakkapel | Dormer |

| Beune | Zolder | Loft |

| Boksem | Broek | Trousers |

| Bolle | Stier | Bull |

| Boudel | Boel/Toestand | Mess |

| Bözzem | Schoorsteenmantel | Mantelpiece |

| Dammit | Zometeen | Right away |

| Edik | Azijn | Vinegar |

| Eelsk | Verwaand/Aanstellerig | Affected |

| Eerdappel/Eerpel | Aardappel | Potato |

| Elkenain | Iedereen | Everyone |

| Gounend | Een aantal (mensen) | Some (people) |

| Hounder, tuten | Kippen | Chickens |

| Hupzelen | Bretels | Braces (Suspenders in American English) |

| Jeuzeln | Zeuren/janken | To nag |

| Jirre | Vies water | Dirty liquid |

| Graimen, klaaien | Morsen | To make grimy |

| Kloede | Klont/Dik persoon | Lump/Fat person |

| Koare | Kruiwagen | Wheelbarrow |

| Kopstubber | Ragebol | Round ceiling mop |

| Kribben | Ruzie maken | To wrangle |

| Krudoorns | Kruisbessen | Gooseberry |

| Leeg | Laag | Low |

| Liepen | Huilen | Crying |

| Loug | Dorp | Village |

| Lutje | Klein/Luttel | Little |

| Mishottjen | Mislukken | To fail |

| Mous | Boerenkool | Kale |

| Mug | Vlieg | Housefly |

| Neefie | Mug | Mosquito |

| Om toch! | Daarom! (nietszeggend antwoord op vraag met “waarom”) | "because I say so"(a meaningless answer to a question with “why”) |

| Opoe | Oma | Grandmother |

| Poeppetoon, Woalse boon | Tuinbonen | Broad bean |

| Puut | (plastic) Zak | (plastic) Bag |

| Plof(fiets) | Brommer | Moped |

| Rebait | Rode biet | Red beet |

| Raive | Gereedschap | Tools |

| Schraaien | Huilen | To weep |

| Siepel | Ui | Onion |

| Sikkom | Bijna | Around |

| Slaif | Pollepel | Ladle |

| Slik | Snoep | Sweets (Candy in American English) |

| Slim | Erg | Very badly |

| Smok | Zoen | Kiss |

| Spèren/spijen | Braken, spugen | Vomiting / spewing |

| Stoer | Moeilijk | Difficult |

| Steekruif | Koolraap | Turnip |

| Riepe | Stoep | Pavement (Sidewalk in American English) |

| Verlet hebben van | Nodig hebben | To need (badly) |

| Vernaggeln | Vernielen | To demolish |

| Weg/Vot | Vandaan | From (as in: “Where do you come from~?”) |

| Wicht | Meisje | Girl |

| Wied | Ver | Far |

| Zedel | Folder | Leaflet |

References

| Low Saxon edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Gronings at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Gronings". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- "Pervinzioale Schriefwedstried". Huis van de Groninger Cultuur. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- Veldman, Fokko (1992). De taal van Westerwolde: Patronen en structuren in een Gronings dialect. University of Groningen.

Further reading

- Reker, Siemon (1999), "Groningen", in Kruijsen, Joep; van der Sijs, Nicoline (eds.), Honderd Jaar Stadstaal (PDF), Uitgeverij Contact, pp. 25–36

External links

- www.dideldom.com

- Groningana

- Kursus Grunnegs Course in Gronings

- Kursus Grunnegs Course in Gronings on line

- Press release Simon Reker has become Regular Chairholder for Gronings at Groningen University YouTube

- Press release New teaching materials for younger pupils YouTube

- Gronings for beginners