Kyrie

Kyrie, a transliteration of Greek Κύριε, vocative case of Κύριος (Kyrios), is a common name of an important prayer of Christian liturgy, also called the Kyrie eleison (/ˈkɪərieɪ ɪˈleɪɪsɒn, -sən/ KEER-ee-ay il-AY-iss-on, -ən; Ancient Greek: Κύριε, ἐλέησον, romanized: Kýrie eléēson, lit. 'Lord, have mercy').[1]

In the Bible

The prayer, "Kyrie, eleison," "Lord, have mercy" derives from a Biblical phrase. Greek ἐλέησόν με κύριε "have mercy on me, Lord" is the Septuagint translation of the phrase חָנֵּנִי יְהוָה found often in Psalms (4:1, 6:2, 9:13, 25:16, 27:7, 30:10, 31:9, 51:1, 86:16, 123:3)

In the New Testament, the Greek phrase occurs three times in Matthew:

- Matthew 15:22: the Canaanite woman cries out to Jesus, "Have mercy on me, O Lord, Son of David." (Ἐλέησόν με κύριε υἱὲ Δαβίδ)

- Matthew 17:15: "Lord, have mercy on my son" (Κύριε ἐλέησόν μου τὸν υἱόν)

- Matthew 20:30f, two unnamed blind men call out to Jesus, "Lord, have mercy on us, Son of David." (Ἐλέησον ἡμᾶς κύριε υἱὸς Δαβίδ)

In the Parable of the Publican and the Pharisee (Luke 18:9-14) the despised tax collector who cries out "Lord have mercy on me, a sinner" is contrasted with the smug Pharisee who believes he has no need for forgiveness.

Luke 17:13 has epistates "master" instead of kyrios "lord" (Ἰησοῦ ἐπιστάτα ἐλέησον ἡμᾶς), being less suggestive of the kyrios "lord" used as euphemism for YHWH in the Septuagint. There are other examples in the text of the gospels without the kyrie "lord", e.g. Mark 10:46, where blind Bartimaeus cries out, "Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me." In the biblical text, the phrase is always personalized by an explicit object (such as, "on me", "on us", "on my son"),[2] while in the Eucharistic celebration it can be seen more as a general expression of confidence in God's love.[3]:293

In Eastern Christianity

The phrase Kýrie, eléison (Greek: Κύριε, ἐλέησον), or one of its equivalents in other languages, is one of the most oft-repeated phrases in Eastern Christianity, including the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches. The various litanies, frequent in that rite, generally have Lord, have mercy as their response, either singly or triply. Some petitions in these litanies will have twelve or even forty repetitions of the phrase as a response. The phrase is the origin of the Jesus Prayer, beloved by Christians of that rite and increasingly popular amongst Western Christians.

The biblical roots of this prayer first appear in 1 Chronicles 16:34

...give thanks to the LORD; for he is good; for his mercy endures for ever...

The prayer is simultaneously a petition and a prayer of thanksgiving; an acknowledgment of what God has done, what God is doing, and what God will continue to do. It is refined in the Parable of The Publican (Luke 18:9–14), "God, have mercy on me, a sinner", which shows more clearly its connection with the Jesus Prayer. Since the early centuries of Christianity, the Greek phrase, Kýrie, eléison, is also extensively used in the Coptic (Egyptian) Christian liturgy, which uses both the Coptic and the Greek language.

In Western Christianity

In Rome, the sacred Liturgy was first celebrated in Greek. At some point the Roman Mass was translated into Latin, but the historical record on this process is sparse. Jungmann explains at length how the Kyrie in the Roman Mass is best seen as a vestige of a litany at the beginning of the Mass, like that of some Eastern churches.[3]:335f.

As early as the sixth century, Pope Gregory the Great noted that there were differences in the way in which eastern and western churches sang Kyrie. In the eastern churches all sing it at the same time, whereas in the western church the clergy sing it and the people respond. Also the western church sang Christe eléison as many times as Kyrie eléison.[1][4] In the Roman Rite liturgy, this variant, Christe, eléison, is a transliteration of Greek Χριστέ, ἐλέησον.

"Kyrie, eléison" ("Lord, have mercy") may also be used as a response of the people to intentions mentioned in the Prayer of the Faithful. Since 1549, Anglicans have normally sung or said the Kyrie in English. In the 1552 Book of Common Prayer, the Kyrie was inserted into a recitation of the Ten Commandments. Modern revisions of the Prayer Book have restored the option of using the Kyrie without the Commandments. Other denominations, such as Lutheranism, also use "Kyrie, eléison" in their liturgies.

Kyrie as section of the Mass ordinary

In the Tridentine Mass form of the Roman Rite, Kýrie, eléison is sung or said three times, followed by a threefold Christe, eléison and by another threefold Kýrie, eléison. In the Paul VI Mass form, each invocation is made only once by the celebrating priest, a deacon if present, or else by a cantor, with a single repetition, each time, by the congregation (though the Roman Missal allows for the Kyrie to be sung with more than six invocations, thus allowing the traditional use). Even if Mass is celebrated in the vernacular, the Kyrie may be in Greek. This prayer occurs directly following the Penitential Rite or is incorporated in that rite as one of the three alternative forms provided in the Roman Missal. The Penitential Rite and Kyrie may be replaced by the Rite of Sprinkling.

In modern Anglican churches, it is common to say (or sing) either the Kyrie or the Gloria in Excelsis Deo, but not both. In this case, the Kyrie may be said in penitential seasons like Lent and Advent, while the Gloria is said the rest of the year. Anglo-Catholics, however, usually follow Roman norms in this as in most other liturgical matters.

Text

- Kyrie eléison (Κύριε, ἐλέησον)

- Lord, have mercy

- Christe eléison (Χριστέ, ἐλέησον)

- Christ, have mercy

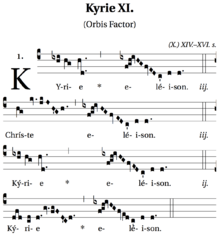

Musical settings

In the Tridentine Mass, the Kyrie is the first sung prayer of the Mass ordinary. It is usually (but not always) part of any musical setting of the Mass. Kyrie movements often have a ternary (ABA) musical structure that reflects the symmetrical structure of the text. Musical settings exist in styles ranging from Gregorian chant to folk. Additionally, the musician Judee Sill emulated the Greek Orthodox delivery of the Kyrie in her song "The Donor" on the album Heart Food.[5]

Pronunciations

The original pronunciation in Medieval Greek was [ˈcyri.e eˈle.ison xrisˈte eˈle.ison], just when the Byzantine Rite was in force. The transliteration of ἐλέησον as eléison shows that the post-classical itacist pronunciation of the Greek letter eta (η) is used. Although the Greek words have seven syllables (Ký-ri-e, e-lé-i-son), pronunciations as six syllables (Ký-ri-e, e-léi-son) or five (Ký-rie, e-léi-son) have been used.

In Ecclesiastical Latin a variety of pronunciations are used, the italianate [ˈkiri.e eˈle.isoŋ ˈkriste eˈle.ison] having been proposed as a standard. Text underlay in mediaeval and Renaissance music attests that "Ký-ri-e-léi-son" (five syllables) was the most common setting until perhaps the mid-16th century. William Byrd's Mass for Four Voices is a notable example of a musical setting originally written with five syllables in mind, later altered for six syllables.

The Mediaeval poetic form Kyrielle sometimes uses Kýrieléis, an even more drastic four-syllable form, which is reduced to three syllables or even to kyrleis in the German Leise [ˈlaɪzə].

In renewed Roman Catholic liturgy

The terms aggiornamento (bringing up to date) and ressourcement (light of the Gospel) figure significantly into the documents of Vatican II: “The Church carries the responsibility of scrutinizing the signs of the times and interpreting them in the light of the Gospel” (Gaudium et spes, 4).[6] Louis Bouyer, a theologian at Vatican II, wrote of the distortion of the Eucharistic spirit of the Mass over the centuries, so that "one could find merely traces of the original sense of the Eucharist as a thanksgiving for the wonders God has wrought.”[7] The General Instruction of the Roman Missal (GIRM) notes that at the Council of Trent "manuscripts in the Vatican ... by no means made it possible to inquire into 'ancient and approved authors' farther back than the liturgical commentaries of the Middle Ages ... [But] traditions dating back to the first centuries, before the formation of the rites of East and West, are better known today because of the discovery of so many liturgical documents" (7f.). Consonant with these modern studies, theologians have suggested that there be a continuity in praise of God between the opening song and the praise of the Gloria. This is explained by Mark R. Francis of Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, speaking of the Kyrie:

Its emphasis is not on us (our sinfulness) but on God’s mercy and salvific action in Jesus Christ. It could just as accurately be translated "O Lord, you are merciful!" Note that the sample tropes all mention what Christ has done for us, not how we have sinned. For example, “you were sent to heal the contrite,” “you have shown us the way to the Father,” or “you come in word and sacrament to strengthen us in holiness,” leading to further acclamation of God’s praises in the Gloria.[8]

In this same line, Hans Urs von Balthasar calls for a renewal in our whole focus at the Eucharist:

We must make every effort to arouse the sense of community within the liturgy, to restore liturgy to the ecclesial plane, where individuals can take their proper place in it…. Liturgical piety involves a total turning from concern with one’s inner state to the attitude and feeling of the Church. It means enlarging the scope of prayer, so often narrow and selfish, to embrace the concerns of the whole Church and, indeed – as in the Our Father – of God.”[9]

In the New Dictionary of Sacramental Worship, the need to establish communion is reinforced as it quotes the General Instruction to the effect that the purpose of the introductory rites is “to ensure that the faithful who come together as one establish communion and dispose themselves to listen properly to God's word and to celebrate the Eucharist worthily” (GIRM, 46, emphasis added).[10]

In various languages

In addition to the original Greek and the local vernacular, many Christian communities use other languages, especially where the prayer is repeated often.

|

See also

References

Citations

- "Definitions for Medieval Christian Liturgy: Kyrie eleison". Yale. Archived from the original on 2013-05-18.

- "Kyrie Eleison". Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- Jungmann, J. The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its Origins and Development. New York 1951: Benzinger Brothers. pp. num. 322ss.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Gregory the Great, Epistles 9: 26, trans. Baldovin, Urban Worship, 244-245

- "Kyrie eleison, kyrie eleison / Kyrie eleison, eleison / Eleison, eleison / Kyrie eleison, kyrie eleison". Genius. Retrieved 2019-06-18.

- Ressourcement: A Movement for Renewal in Twentieth-Century Catholic Theology. Chapter 24, Ressourcement and Vatican II. Oxford. 2011. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199552870.001.0001. ISBN 9780199552870. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- Eucharist. Notre Dame University. 1989. ISBN 978-0268004989., p. 318

- 'Well Begun Is Half Done: The New Introductory Rites' in The Revised Sacramentary in Liturgy for the New Millennium: A Commentary on the Revised Sacramentary: Essays in Honor of Anscar J. Chupungco. Ed. Mark R. Francis and Keith F. Pecklers. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press. 2000. ISBN 978-0-8146-6174-1. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- Church and World. Herder and Herder. 1967. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- New Dictionary of Sacramental Worship. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press. 1990. pp. 944f. ISBN 978-0814657881.

- Jumalanpalvelusten kirja (PDF) (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kirkkohallitus. 2000. pp. 16–17. OCLC 58343251.

- Berndt, Guido M. (2016-04-15). Arianism: Roman Heresy and Barbarian Creed. Routledge. ISBN 9781317178651.

Sources

- Hoppin, Richard. Medieval Music. New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1978. ISBN 0-393-09090-6. Pages 133–134 (Gregorian chants), 150 (tropes).